Полная версия

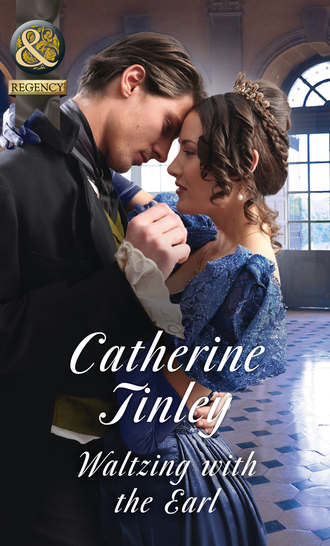

Waltzing With The Earl

Mr Foxley, who was opposite Charlotte, was also suffering from a lack of conversation. He had the felicity of being seated between Mr Buxted and Henrietta, neither of whom were offering him attention. He ate sparingly and, though he tried to disguise it, his focus kept being drawn to Faith and Captain Fanton.

Mrs Buxted was smiling approvingly as her two daughters held the attention of the Fantons. Charlotte shamelessly listened in on each exchange. Nothing of note was being discussed. Nothing interesting, nothing meaningful. Nothing.

She had sat through enough society dinners to know this was usual—even commonplace. Even by those standards, however, the lack of insight and intelligence being displayed by the two Buxted ladies was positively shocking. Perhaps, she thought, girls in England were brought up to be so sheltered and protected it meant they had no opinions to offer—at least in public.

The Captain seemed perfectly comfortable to continue to extract some little conversation from the shy Faith—currently on the topic of how best to get through a long coach journey. On the far side of the table Henrietta was prosing on about correct behaviour for young ladies, and how grateful she was to have a dear mother who had taught her exactly how to go on.

The Earl’s eyes were positively glazing over, Charlotte thought, trying to hide her amusement. Her eyes danced with mischief—just as he looked up and caught her gaze. Although discovered, she would not hide, and instead continued to twinkle at him impishly. Surprisingly, he responded with an unthinking, companionable smile of his own before checking himself.

Too late! Henrietta had caught the spontaneous interaction between them. Her eyes blazed.

‘For an English upbringing,’ she said loudly, drawing all eyes to her, ‘is infinitely better than a savage youth spent among soldiers and foreigners. Don’t you agree, Lord Shalford?’

Chapter Five

Sudden silence surrounded the table as the shock of Henrietta’s rude comment was felt. It was clearly directed at Charlotte, though it was not obvious to the other diners what had triggered the attack. The Earl looked confused, as if wondering what was going on between the cousins.

Charlotte, despite what she knew of Henrietta’s spoiled behaviour, was stunned—and surprised that her cousin had exposed herself so blatantly. The exchange between herself and the Earl had been a spontaneous, meaningless moment—nothing to threaten Henrietta’s position as the Earl’s target of interest.

Henrietta was so self-involved—and yet so uncertain of herself. She thought nothing of behaving in an aggressive, unladylike and hurtful fashion. Charlotte, whose own anger had now been roused, was sorely tempted to retort in like manner, but she could not. To respond—even to speak directly across the table—would be ill-mannered and would simply confirm Henrietta’s accusations.

As the tension increased Charlotte clenched her cutlery tightly and then, deliberately dropping her gaze, carefully cut a piece of turbot and brought it to her mouth.

As she chewed slowly, tasting nothing, she heard Lord Shalford’s response.

‘I think,’ he said smoothly, ‘that it rather depends. I have no doubt there are many people abroad and in England who show a lack of refinement—just as there are many who will have been brought up well.’

Henrietta subsided, with a confused expression and bright red angry spots on her cheeks.

Oh, bravo! thought Charlotte. He speaks so subtly she is not even sure of his meaning.

The Earl rose a little in her estimation. She raised her eyes to his briefly, trying to communicate her gratitude. He met her gaze, his eyes softening.

Captain Fanton, turning away from Faith, claimed Charlotte’s attention. ‘I must tell you, Miss Wyncroft, I enjoyed our canter through the park.’

Charlotte smiled gratefully. ‘As did I. We will ride again on Tuesday?’ Thankfully, her voice was steady, even if her hands—hidden now on her lap—were not.

‘Yes, indeed. I will look forward to it!’

Across the table, the Earl once again engaged Henrietta in conversation and the tension slowly eased.

* * *

After dinner, thankfully, there was no time for the ladies to retire to the drawing room, for the carriages were ready. When they rose from the table, as the servants swooped in to clear the remains of the meal and help the Buxted ladies with their boots, gloves and cloaks, Lord Shalford made a point of speaking with Charlotte.

‘I do hope,’ he said quietly, ‘you were not distressed by the conversation earlier.’

About to deny it, she caught the quiet sincerity in his grey eyes and relented. It was good of him to be concerned about her. There was no trace of arrogance about him now.

‘I thank you for coming to my rescue. The worst of it is she is right! I wished for nothing more than to give her pepper—even at the dinner table. My temper is not easily aroused in the normal run of things. I have learned I am truly an ill-bred hoyden at times.’

He shook his head. ‘I think not. I admit I was a little surprised by your cousin’s comment.’

Charlotte did not wish him to think ill of Henrietta. ‘She was upset...perhaps thinking we were making fun of her. Her reaction was understandable in the circumstances.’

‘You are too considerate, I think.’

‘My cousin is young, and not long out. She can be over-sensitive.’

‘Now you sound like an elderly matron. Yet you cannot be more than nineteen!’

‘I lack only a few weeks until my twenty-first birthday.’

‘Then you and Miss Buxted are of an age, for she tells me she will be twenty-one on the first of August.’

‘I am a little older than her. That is why my father thought we should be such friends. Unfortunately...’ She stopped.

He raised an eyebrow. ‘So you and Miss Buxted are not close, then?’

‘Well...we are very different people.’

He considered this. ‘Yes,’ he said slowly. ‘I think you are.’

For some reason, this made him frown.

Belatedly, she realised the impropriety of speaking to him so frankly. ‘Henrietta has many admirable qualities, and I know I can be extremely irritating.’ She laughed lightly. ‘Papa allows me no self-delusions. My upbringing and experiences have been so different from Henrietta’s it is hardly surprising we do not always see eye to eye.’

He nodded. ‘We must also allow that young ladies in general are prone to heightened emotions and to behaviour which would be deplored in a man or an older lady. Debutantes must be forgiven their...’

‘Silliness?’ she offered tartly, remembering his judgemental comment about her.

He looked startled, but did not disagree. ‘What of tonight’s ball?’ he asked, in an attempt to divert her. ‘Do you mind that you do not go?’

‘Well, I thought I did not mind very much. Though now, when you are all ready to go, elegantly dressed and full of anticipation, I confess I do wish I was going with you. I hope you do not think me ridiculous, but I do like to dance now and again.’

‘You are not ridiculous at all,’ he said. ‘I should have liked to see you dance. I confess it does not sit well with me, leaving you here while we all go out. Is there no way you could have gone?’

‘I must be guided by my aunt. She assures me it would not be proper for me to go to a large London ball when I am not yet out. I was too late to be presented at Court this year. I have not lived in England, and I do not know these things myself.’

‘I see,’ he said, frowning slightly.

‘Lord Shalford!’ Henrietta’s strident tone interrupted their tête-à-tête. ‘The carriages are ready and we must go, for I should hate to miss the dancing. I adore dancing!’

The Earl bowed to Charlotte, smiled a rueful farewell, and took his place by Henrietta’s side.

‘Charlotte,’ said Henrietta sweetly, ‘do enjoy your quiet evening. You will be glad to see us gone, I am sure.’

‘Such a pity you cannot come to the ball,’ offered the Captain, sincere regret in his blue eyes. ‘Our party will not be the same without you. Will you be very lonely?’

Mrs Buxted looked displeased.

Charlotte hurriedly denied it, adding, ‘I hope you all enjoy your evening. I shall indeed enjoy the peace and quiet.’

They moved to the hallway, where the men were handed their hats, cloaks and canes. Charlotte stood back, wishing them gone, for this protracted farewell was difficult.

Finally they all moved to the door. At the last, the Earl turned to look at her, and his expression was strangely uncertain.

‘Come, Lord Shalford!’ Henrietta’s tone was imperious. ‘You shall travel in our carriage, for I must tell you more of my visit to Oxford.’

Then they were gone.

* * *

Charlotte hoped they didn’t pity her. She imagined them all, travelling to Lady Cowper’s townhouse. Henrietta would be enjoying her triumph, while Aunt Buxted would be focused on gaining every possible advantage for her daughters. Mr Buxted would already be thinking of meeting his cronies in the card room, and wondering what would be offered at supper.

Faith, with her kind heart, would not feel fully comfortable with Charlotte’s absence, but would be ably distracted by the charming Captain Fanton—and by the gentle Mr Foxley. As for the Earl—no doubt his attention would be fully claimed by the beautiful, wilful Henrietta.

Charlotte went to the library, then to the salon. She was at a loss as to what to do. She felt strangely flat, which surprised her, for she had not thought herself so shallow that the loss of a ball should so affect her. She was not ready to sleep, and reading could not hold her attention. She tried to write a letter to Papa, but the words would not come, and she sat down her pen in frustration.

After almost two hours of achieving nothing, she went to her room.

Priddy helped her prepare for bed, and expressed her opinion on balls and Court presentations and on. ‘Old women who have forgotten what it is to be young. Mark my words: she only did it to keep you away from the young gentlemen!’

‘Oh, Priddy! You must not say such things. It will make me even more angry, for I fear you are right. But we may be wrong. Why, when Henrietta was angry about my riding with them Aunt Buxted did not support her.’

Priddy snorted. ‘She’s a clever old bird. She has plans for her daughters and she will not brook opposition.’

‘But I am no opposition for her daughters. I have no wish for a husband, and I cannot match my cousins’ beauty.’

‘I do not understand how you can say you are not beautiful. You are no insipid yellow-haired milkmaid, it is true, but that is just a fashion. You have countenance, Miss Charlotte, and your good looks will last longer than Miss Buxted’s, mark my words.’

‘Oh, Priddy, I know your regard for me deceives you, but I thank you nevertheless.’

Priddy shook her head. ‘That’s not it. And as for not wanting a husband—it is every girl’s wish to get a nice husband.’ She stared into the distance. ‘To have a proper home of your own and little ones.’

‘Even you, Priddy?’ Charlotte was curious.

‘I confess when I was young there was a man.’ Her eyes softened. ‘We were to be married. But he was carried off by a fever. It was not to be.’

‘Oh, Priddy! I’m so sorry.’ Impulsively, she hugged the woman who had been the closest thing to a mother to her since she had lost her own mama.

‘Now, now,’ said Priddy gruffly. ‘It was a long time ago. But if you get the chance at happiness you must take it. We none of us know how long we have on this earth.’

Charlotte pondered Priddy’s words as she lay wide awake, listening to the sounds of the city at night—carriages rumbling, dogs barking, in the distance, some drunken singing. She knew better than most how easily lives could be snuffed out. Growing up as a war child, she had known many people to die—officers, foot soldiers and their wives—more often from illness and disease than from the heat of battle. She wondered if Captain Fanton, like many of the young men she had known, had felt the trauma of war and of loss.

Her mind moved on from the Captain to his brother. The Earl had been kind tonight. Not arrogant at all. She remembered his cool grey eyes fixing upon hers and felt a strange warmth in her chest. It was altogether confusing, for he held young ladies in disdain, and the squabble between Henrietta and herself would only have strengthened his prejudice.

Yet, surprisingly, her view of him was changing. Where she had seen arrogance and prejudice, she now saw warmth and compassion. Even more strange was this new feeling he had stirred in her. It was something like...affection, though there were other, stranger colours in it. It was a good feeling, though somewhat overshadowed by imagining them all at the ball.

She pictured them all, dancing, laughing, talking, and felt...alone.

Chapter Six

Lady Sophia Annesley was in her drawing room when Adam called. As the Earl was a regular visitor, and one who was well known to all of her ladyship’s staff, he was shown straight in. Unfortunately when he arrived, Lady Sophia was stretched out on a sofa, gently snoring, a handkerchief over her face to protect her sensitive eyes from the harsh daylight.

Adam coughed discreetly.

She rose with a start, her cap slipping sideways and the comfortable blanket she had spread over her feet falling to the floor.

Retrieving the blanket, the Earl bent to help her into a sitting position and kiss her cheek. ‘Good day, Godmama. What a fetching cap!’

‘For goodness’ sake, Adam, why do you arrive without warning? You should always allow a lady to be ready for a visitor.’

She waved at him to be seated, so he placed himself beside her on the sofa.

Lady Sophia was a lady in her middle years, with a round figure and a pleasant, friendly visage. Her mind was sharp, and she knew everyone in society, keeping track of the latest on-dits through her extensive network of friends. She was well-known and popular, though some were wary of her, for she spoke her mind and was scathing of those she termed ‘fribbles, fools and imbeciles’.

Just now, she did not look quite so formidable.

Retying her cap under her left ear, and gathering her thoughts at the same time, Lady Sophia surveyed the Earl. He looked fresh and immaculately groomed. His boots were polished to a high gloss, his neckcloth perfectly tied, and his eyes clear and amused. Yet she knew he—like most of London’s elite—had drunk and eaten, danced and talked until the early hours of the morning at Lady Cowper’s ball.

‘Why are you so awake and so loud at this ungodly hour? I am not long arisen from my bed.’

‘But it is almost two o’clock.’

‘Yes, but it feels like the middle of the night! I believe there was something wrong with those prawns, you know, though I would never say so to Emily Cowper. I feel distinctly unwell.’

‘Well, you look as fresh as a newborn lamb, despite...er...the copious amounts of punch on offer last night.’

She eyed him malevolently. ‘Yes, thank you, Adam, but you really shouldn’t be barging in unannounced, you know.’

‘Aunt Sophia, you summoned me here. I dashed from my bed when I received your message, wondering what desperate crisis had occurred. I came as quickly as I could!’

‘Foolish boy! I have no time for your funning today.’ She patted his hand warmly, but then spoke intently. ‘Something of a most concerning nature has occurred.’

‘Do tell, pray.’

‘Last night at the ball the Fanton name was being bandied about in a most unpleasant way.’

He frowned. ‘Indeed? May I ask what was said?’

‘There’s the thing. I don’t know exactly. But I know the sort of tittle-tattle and gossip...’

‘Ah.’ He sat back. ‘And was this gossip perhaps related to the fact that we were part of the Buxted party at the ball?’

‘I cannot like it, Adam. We are Fantons. We should not be the subject of demeaning conversation from people with nothing else to do.’

‘What are the old tabbies saying? What can they possibly find amiss in our company last night? The Buxteds are a respectable family whose Surrey estate marches with ours. Why, we may have known them for a long time.’

‘Yes, but it is known you have never been intimate with them. It is drawing attention. It seems Mrs Buxted has been crowing about you visiting their house and having dinner, arranging riding excursions...’ She paused. ‘There are even rumours that the entire family have been invited to Chadcombe.’

‘And what if they have?’

She looked shocked ‘But, Adam, you must know it is too particular... It looks as if you may be planning to offer for one of the Buxted girls. Now, I must say since your father’s illness, and this last year, you have surprised all the naysayers who thought you would struggle to manage Chadcombe. I know as few do how things were let slip these last few years, with your mama gone and your father not himself...I also know how you are working hard to repair and improve the estate. You have behaved admirably, my boy. But there is no need to set up your nursery too soon, you know. Better to wait a while for the right girl to come along.’

The Earl remained expressionless.

She took his hand. ‘Tell me, Adam, do you think of marriage?’

‘Yes—no! I don’t know.’ He smiled ruefully. ‘I had thought it sensible, but unfortunately I am having some difficulty in actually deciding to...well, to cross that particular Rubicon. I have had my fill of debutantes. They giggle and simper and talk too much—or not enough. Or they have no opinions. Or they have ill-informed opinions. Or they are...impudent.’

He rose, trying to shake away the memory of one particular young lady, and made an absent-minded study of Lady Annesley’s ormolu clock on the mantel.

‘I must at least consider it, Godmama. It is my duty to marry well. Grandfather almost ruined us, and Papa worried himself into an early grave trying to restore our fortunes. I have made a good start on the estate, but the house has lost some of its warmth since Mama died. It needs a mistress. And Olivia needs female company—someone other than Great-Aunt Clara. Olivia and I argue too much lately. I do not understand what goes on in the mind of a woman!’

‘What do you and Olivia argue about?’

‘She chafes against the restrictions of Chadcombe. She wishes to come out next season, now we are out of mourning, but in truth I cannot stomach the thought of squiring her to dozens of balls and routs. And as for Almack’s—with its orgeat and its gossips—’ He grimaced. ‘I have been trying hard this season to take my place in the Marriage Mart, but the whole game quite disgusts me!’

‘Adam, you have had it your own way for far too long. No, do not show me that face. I am not a debutante, to be slain by your wrathful looks. I am your aunt and your godmother and I shall tell you what I think.’

‘I am all attention, dear Aunt.’

‘You are a good boy, Adam. You work hard with the estate and your interest in politics does you credit. My brother—your poor father—would be proud of you. But you are accustomed to deference, and to having what you want. You have the freedom to go where you will, whenever you wish—to gambling dens, cockfights, boxing matches and other uncouth pursuits if you wish. You have independence. Try to remember Olivia does not.’

‘Olivia is well cared for. My great-aunt—’

‘Clara Langley is too old to be a fitting companion for a young lady. You know I love your mother’s elderly aunt, but she does not wish to go out in society and has no understanding of the needs of a young girl like Olivia.’

‘Which is why I must marry! My...my wife—’ he struggled with the word ‘—will look after Olivia, help her with her come-out and—’

‘But that is not a reason to marry. Why, I could take dear Olivia under my wing.’

‘Come, come, Aunt Sophia. You would hate it after a week. Like me, you are accustomed to independence. Since my uncle died—and I know you grieve deeply for him—you have built a good life as a widow, have you not?’

‘You know me too well. But, Adam, I will do it. If you do not find a lady you truly wish to marry—a lady you love and wish to share your life with—then I will bring Olivia out next season. There!’

He kissed her hand. ‘Best of aunts. I thank you—though I still believe you would detest it. How would you survive Almack’s every week?’

She struggled to answer.

‘Exactly!’

‘Wretch! Now, tell me—what of Harry? His name is being linked with the Buxted girls too, with speculation that he will also marry.’

The Earl considered this, his forehead creased. ‘I cannot say, for Harry no longer confides in me. He enjoys female company, and can flirt and make compliments much easier than I. But I do not know if he thinks of marriage... The wars have changed him, Godmama. Underneath the gaiety, he is still troubled, I think.’

‘He is young. Time will help him forget what he has seen. Now we have peace, and will not be murdered in our beds by Frenchmen, he can enjoy his duties without anxiety. You shake your head—do you disagree with me?’

‘I cannot be easy about Harry. He hides it well, but... I am being foolish, perhaps. Too much time to think and worry and ponder over things. And now this unfortunate mess. I am displeased that my attentions to the Buxted ladies have been noticed—and not just on my own behalf. I should not like to cause distress to any lady—and I should like the freedom to make my choice without an audience watching my every action.’

‘Tell me, have you invited them to Chadcombe? Just the mother and the daughters?’

‘I have—but not just Mrs Buxted and her daughters. The father too. And a relative who is staying with them.’

‘And who is your hostess? Clara?’

‘Yes, she has agreed to host. I know she struggles to manage the house at times, but she assures me she is happy to host this party.’

‘Good. May I advise you?’

‘Of course you may. You are, after all, my favourite aunt.’

‘I am your only aunt. Now, do listen, Adam. Mrs Buxted, from what I know of her, is a vain, silly woman who is ambitious for her daughters. She was Louisa Long before her marriage, and those Longs were always a little... Yes, well, she thinks she has triumphed because of the exclusivity of this invitation to Chadcombe. And, in truth, the exclusivity is what is stirring the gossips. If you have truly only invited them—’

‘Godmother, I thank you. I shall immediately invite a dozen eligible ladies and their families to divert suspicion.’

‘No, not a dozen. Poor Miss Langley—! Ah, you are jesting with me again, I see. Yes, do invite others to Chadcombe. And it would be wise to be seen escorting other young ladies as well—perhaps take one to the theatre with her family. That way, if you do choose to court one in particular, you can do so without giving ammunition to the gossips. But, Adam, listen to me now. Things have changed. In these modern times you do not have to marry out of duty. Better marry for love.’

‘Love?’ He laughed. ‘I have no desire to spout poetry and daydream of a lady’s fine eyes...’

He paused, then shook his head as if to rid himself of something.

‘I just want to find a sensible girl who won’t give me any trouble. I must think of the estate. We are in need of money, so I must marry well. The Buxted family owns Monkton Park, which would be a good addition to Chadcombe, and the mother rather clumsily informed me it is dowried on one of the daughters. On the other hand, Miss Etherington has a large dowry, which would boost our funds. And there is another lady—but I do not know what her fortune is.’

‘But, Adam, you have done well with the estate since your father died. Don’t forget that the woman you marry will be by your side till death parts you. You must think of that when you choose to marry.’

‘My problem, Godmama, is that I have never yet met a lady—apart from you, of course—who did not bore me or irritate me within a month of knowing her. And marrying to suit myself is not an option if it causes harm to my family.’