Полная версия

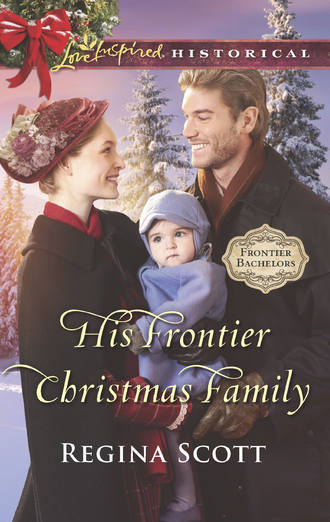

His Frontier Christmas Family

“Just you wait, Callie,” Pa would say, eyes bright and cheeks flushed like he was feverish. “One day you’ll dress in fine silks and live in a big house with servants to do all the work.”

He’d had a fever all right. Gold fever. This preacher seemed no different.

“We get by,” she told him, warmed by her brothers on either side. “What are you offering that’s any better?”

He took a step closer and spread his hands, as if intent on making his case. He had nice hands, strong-looking and not too soft, like he could wield a pick or shovel if he needed to. He was slender for a man, but those broad shoulders and long legs seemed made to crouch beside a stream for hours panning.

And when had she started judging men by their ability to hunt for gold!

“I have a solid house,” he said, “with a good roof and a big hearth.”

That would be nice. Frisco and Sutter kept having to reposition the tick they slept on to stay out of the drips from the roof when it rained.

“Our house is solid,” Frisco blustered.

The preacher had to know that was a lie, but he inclined his head again. “I also have a kitchen stove, plenty of food set aside for winter, a separate bedroom and a sleeping loft overhead.”

Her brothers brightened, but Callie had spotted the fly in the ointment. “Who do you figure’s sleeping in the bed?” she asked.

His brows shot up. Preachers—they never liked to talk about practical things, like sleeping arrangements or taking turns in the privy.

“You and the baby would have the bedroom,” he assured her. “I’ll bunk in the loft with the boys.”

Sutter and Frisco looked around her at each other, and she was fairly sure they didn’t like the idea of having the preacher so close at night. She’d heard them open the shutters in the loft after they were supposed to be asleep, the thud of their feet against the logs as they climbed down. And she’d stayed awake until she’d heard them climb back up again.

Still, she couldn’t believe the preacher would be so generous. “You’d take us into your own home,” she challenged. “People you barely know?”

He smiled. “I knew Adam. He saved my life once, gave me food when I was starving. I was his friend. That makes us friends, too.”

Friends, he said. She had had few over the years, young men her age mostly, and they’d quickly lost each other as families traveled to different strikes. She couldn’t believe this man was her friend. She couldn’t make herself believe any of it—Adam’s death, this stranger’s kindness. Either Levi Wallin was one of those do-gooders who donated to the poor only to brag about it, or he was after something.

“We don’t need your pity, preacher,” she said.

He smiled. Such a nice smile, lifting his lips, brightening his eyes. She could imagine people doing anything he wanted when he smiled at them that way.

“I’m not offering to help you from pity,” he promised her. “Adam asked me to look out for you. Some people might say he gave me guardianship of you all.”

Her brothers stiffened. So did Callie.

“Don’t much care what others say,” she told him. “I don’t need a guardian. I’ve been taking care of my family since I was twelve. And I’ll reach my majority in six months.”

He didn’t argue the fact. If he really did remember Vital Creek, he’d know about the parties Pa threw on any of his children’s birthdays, with music and treats. Anyone who recalled those would know she would turn one-and-twenty in the spring.

“Still, Adam asked me to take care of you,” he pointed out. “Perhaps you’d like to read his letter now.” He turned for the front door before she could respond. “I’ll be right back.” He strode out of the house.

Frisco and Sutter ran after him to peer out the cracks in the shutter.

“He has a horse,” Frisco reported.

“A nice one,” Sutter agreed.

They would know. They’d seen their share of sway-back nags over the years.

“He talks nice, too,” Frisco acknowledged. He turned from the shutter. “Do you think he’s telling the truth, Callie?”

She shrugged. “Even if he was, would you want to live with a preacher?”

Sutter stepped closer to Frisco, nudged his shoulder. Most folks thought her brothers were identical, but she could tell the difference. Frisco was a little bigger, a little heavier, and Sutter’s eyes had more gray in them. Frisco was the leader, Sutter the follower. And both looked to Callie to make the hard decisions.

Like now, when this stranger wanted them to leave the only home they’d ever known.

The preacher returned, crossed to her side and handed her a piece of paper, even as her brothers came to join them. He’d left the door open as if to give her more light to read by, but the little black lines and dots still swam before her eyes.

Were these really Adam’s last words?

She handed the letter to Frisco. “Here. Read it aloud.”

Her brother swallowed, then looked down at the paper.

“Callie, Frisco, Sutter and Mica,” he started, each word slow as he sounded them out. He glanced up at Callie with a grin. “See there, Callie? That’s my name next to yours.”

The preacher smiled as if he appreciated her brother’s excitement. Between their moves and the remote location of the claim, Frisco and Sutter had never been in school, but Callie took pride that they had learned their letters from Anna.

“I see it,” she told Frisco. “Read the rest.”

He bent over the paper. “I promised you all to come back before winter, but I think I’m done for.”

Sutter sucked in a breath, and Frisco looked up again, face paling.

“Go on,” Callie said, throat tight.

“Real cold up here. You remember. But don’t worry. Levi Wallin will take care of you. He knows about living like we did. He understands.”

Callie looked up to find Levi watching her. No one who hadn’t lived in the camps could appreciate the life they’d led. Even the townsfolk in Seattle called her and her brothers wild, uncouth, like they were animals instead of people. Levi Wallin might have visited the gold fields, befriended Adam, but he was still a preacher.

“Tell Mica about me when she asks,” Frisco continued, voice wavering more from emotion than reading skills now, Callie thought. “Tell her I loved her and her ma. Tell her I only wanted to dress her in fine silks and give her a big house with servants.”

Callie dashed a tear from her cheek. She’d tell Mica about Adam, but never that he’d wasted his life, like his father before him, chasing after a fool dream.

“Think of me kindly,” Frisco finished with a sniff. “Your loving brother Adam.”

Sutter’s face was puckered. “Why’d he have to go and die?”

“Everyone dies,” Frisco said, crumpling the note in his fist. “Ma, Pa, Adam, Anna. Callie will die one day. So will you.”

“I won’t!” Sutter shouted, giving him a shove.

“Boys!” Callie blinked back tears. “That’s enough. Frisco’s right—everyone dies someday. It might be sooner or it might be later. None of us knows.”

As Frisco rubbed at his eyes with his free hand, she gathered him closer. Sutter crowded on her other side. Adam was really dead. He and Pa had fought with the fellow who’d tried to buy her. Now it looked as if her brother had simply given her away. Didn’t he think she could raise the boys and Mica alone? Hadn’t he trusted her? What was she supposed to do now?

“I remember how it felt to lose my pa,” the preacher said, in a quiet, thoughtful voice that was respectful of what they were feeling. “I was eight when he was killed in a logging accident.”

So maybe he knew a little about loss. Frisco didn’t respond, but Sutter raised his head. “What did you do?”

“I relied on my family and friends,” he said.

Now Frisco looked up at Callie. “You’re family, Callie. What do you think we should do?”

At least her little brothers trusted her. Even Mica was regarding her with hope shining in her blue eyes.

Still, what choice did she have? She’d been counting on Adam returning before the freeze set in. She needed another pair of hands to get everything ready for winter. Her brothers were too young yet for some of the tasks, and they weren’t very good about taking care of Mica so she could work elsewhere on the claim. They kept finding more interesting things to do, leaving the baby unattended. But she couldn’t hunt or chop wood carrying a baby.

Besides, with Adam gone, how could they keep the claim? She couldn’t file for her own for another six months.

She met the preacher’s gaze. Once more that deep blue pulled her in, whispered of something more, something better. If only she could make herself believe.

“I think,” she told her brothers, “that we should get to know Adam’s friend a little better.”

* * *

Levi smiled. Though he liked to think he’d outgrown the grin Ma had always called mischievous, he knew a smile could go a long way toward calming concerns, soothing troubled hearts. The Murphys had no reason to trust him other than a recommendation from their dead brother. A brother who might still be alive if he hadn’t yielded to the siren’s call of gold.

“You live around here, preacher?” Callie asked him.

They were all watching him. Even the baby blinked her eyes before fixing them on his face as if fascinated.

“I’m the pastor of the church at Wallin Landing, up north on Lake Union,” he told them. He still couldn’t quite believe it. He’d tutored under a missionary on the gold fields, traveled to San Francisco to be trained and ordained. He’d intended to return north to the men who needed hope in the gold rush camps, to help Thaddeus Bilgin, his mentor. Then he’d discovered that his family had built a church and was ready to request a pastor. They couldn’t know how they’d honored him by offering him the role. His first duty had been to perform the marriage ceremony for his closest brother, John, and his bride, Dottie.

But Callie didn’t look impressed that he was the pastor of a church at such a young age. Her eyes were narrowed again. “Levi Wallin, Wallin Landing. Must be nice to have a family who owns a whole town.”

He’d never considered his family wealthy, until he’d left them. Now he knew they had riches beyond anything he would have found panning—love, friendship, encouragement, faith. Still, he didn’t want to give Callie the wrong impression and have her be disappointed when she saw Wallin Landing.

“Not much of a town,” he explained. “Yet. It was our pa’s dream to build a community. We have a church, a store and post office, a dispensary and a school.” He nodded to her brothers. “My brother James’s wife is the teacher. You could learn all kinds of things there, boys.”

First Frisco and then Sutter nodded. At least, he thought he had the names pinned to the right person.

Frisco stuck out his chin. “I reckon we know enough without going to some stupid school.”

“And I reckon there’s always more to know,” Callie countered. She held out the baby to him. “Here. Take Mica for a ride in her wagon. Leave the door open so I can see you. No running off this time. Me and the preacher need to talk.”

Frisco accepted the baby, who babbled her delight at his company. With looks that held a world of doubt, the twins headed for the door.

Callie took a step closer to Levi. Her hair was parted down the middle and plaited to hang on either side of her face, making her look sad and worn. But even if it had been pinned up like most ladies wore it these days, he thought she’d still look sad. She certainly had reason.

“Did they give him a good burial?” she asked.

If someone from Seattle had asked him that question, he would have extolled the wisdom of the minister who delivered the eulogy, numbered the attendees who had honored the deceased with their presence and described the casket and the flowers. After watching men die in the northern wilderness, he was fairly sure what Callie was really asking.

“A team of six men buried him good and deep. Nothing will disturb Adam’s rest.”

She nodded, shifting back and forth on her feet as she gazed out the open door. With a rattle, the boys passed, dragging a rickety wagon with Mica bundled in the bed. He heard Callie’s sigh, felt it inside.

“I’m sorry,” Levi said. “He was too young to die.”

“So was Anna,” she murmured, rubbing at her arm. “That’s Mica’s mother. Our ma and pa died too young, for that matter. Pa stayed in the stream so long he contracted pneumonia. I wouldn’t be surprised if Adam went the same way.”

She and her little brothers had seen too much death. She was younger than his sister Beth. She ought to be giggling over fashion plates, planning for a bright future. What sort of future had her father and brother bequeathed her? She was all the family the boys and the baby had left. The need to help her was so strong that he wondered she couldn’t see it hanging between them.

“A man I knew at Vital Creek was fond of saying that life is for the living,” he murmured. “What do you want to do with your life, Miss Murphy?”

She made a face. “Not so much a matter of wanting as what must be done. Frisco and Sutter need to go to school, learn a trade. I won’t have them dying with a pan in their hands, too. And someone has to raise Mica.”

Levi closed the distance between them, put both hands on her shoulders. Though they seemed far too narrow, there was a strength in them. “What about Callie? Do you want nothing for yourself?”

Her gaze brushed his, and for a moment he thought she’d confess some dream of her own. Then she shrugged as if dismissing it. “You do right by my kin, preacher, and I’ll be satisfied. I can always find my own way later.”

So brave. He might have given another woman a brotherly hug to encourage her, but something told him Callie wouldn’t take kindly to the gesture. She was all prickles and thorns, a hedge thrown up in defense of the heart within, he suspected. He wasn’t sure how to convince her he only meant the best for all of them.

Lord, I thought You sent me here. I thought You were offering me a chance to be the man You want me to be. Give me the words. Help me win her over, for her sake and mine.

“You don’t believe I’ll take care of you all,” he said aloud.

She shrugged as if she didn’t believe much of anything.

He released her shoulders. “I want to help you, Miss Murphy. Adam supported me when no one else would. I want to honor his wishes.”

She scrubbed at her cheek, but not before he saw the tears that had dampened them. “Adam’s gone. Besides, it wasn’t as if you two were partners.”

Partners. The most sacred of ideals where she came from. And that gave him an inkling of how to proceed.

“We weren’t partners,” he acknowledged. “But you and I might be.”

She turned her gaze his way again. “How do you figure?”

“We both want the best for your brothers and little Mica. We should work together.”

She cocked her head. “I’m listening.”

“You, your brothers and Mica can come to live at Wallin Landing as my wards. I’ll see your brothers and Mica clothed, fed, housed and educated. I’ll help you find a future for yourself.”

Still she regarded him. “How do I know I can trust you?”

“When two people decide to partner on a mining claim, how do they know they can trust each other?”

“They give their word and shake hands,” she allowed.

“I give you my word that you and your family will be safe at Wallin Landing.” He stuck out his hand.

She eyed his hand, and for a moment he thought she’d refuse. Then she slipped her fingers into his, sending a tingle up his arm. “And I give you my word to help you raise Frisco, Sutter and Mica,” she said.

He shook her hand. “Partners?”

“Partners for now,” she agreed. “But don’t expect anything more.”

Releasing her, Levi frowned. “What more would I want?”

She shook her head. “Sometimes you ask the silliest questions for a man who claims to have been on the gold fields. You just hold up your end of the bargain, preacher, or this will be the shortest partnership you ever heard of. Wallin Landing may be north of Seattle, but I can still walk away.”

Chapter Three

Levi Wallin came back the next day with a wagon. By that time, Callie had talked herself into going with him.

She had a number of concerns. For one thing, she still wasn’t sure she’d made the right decision by agreeing to partner him. It was fine and good to say he wanted to help, but once he was back at his church, everything neat and tidy and clean, surely he’d start to regret his promise to her. What sort of fellow willingly took on four more mouths to feed, the raising of two boys and a baby? She’d accepted that responsibility out of love; she was kin, after all. What was Levi Wallin’s reason?

He said he had been Adam’s friend, and it seemed he owed Adam a favor for helping him. This was a mighty big favor. The preacher might recall some of the same events she did at Vital Creek, but she didn’t remember meeting him there, couldn’t see his face along the crowded stream of her memories. Charity only went so far, and this partnership was a fair piece further. She simply couldn’t figure him out.

And their visitors didn’t make matters easier.

Carrying Mica in her arms, she’d walked the mile to the Kingerly claim to confirm the elderly farmer had indeed given her brothers the pumpkin and turnips they’d dragged home. She’d returned to find two men with her brothers at the back of the cabin. Their rough, heavy clothing and the pans affixed to their horses’ trap told her what they were before they introduced themselves. Zachariah Turnpeth and Willard Young claimed to be prospectors heading home for the winter. They begged a room for the night. It was one of the unwritten rules of the gold fields. You shared bedding, food, drink, clothing, equipment. About the only thing you didn’t share was your claim. Only the worst of the worst came between a man and his claim.

But she wasn’t about to let strangers stay in the cabin.

“You can pitch your tent out back,” Callie told the older men. “We’ve no grain for the horses, but you’re welcome to share our dinner.”

Her brothers scowled at her as if they thought she should be more generous. As little food was left, she knew she was being generous indeed.

The twins were quick to quiz the prospectors on where they’d panned, what they’d done as she’d fed them all roast pumpkin and turnips.

“Alike as two peas in a pod,” Zachariah said with a smile to Callie.

“Puts me in mind of Fred Murphy’s young’uns at Vital Creek,” Willard agreed. “They’d be around seven now.”

Callie looked at them askance, but Frisco puffed out his chest. “Eight,” he declared.

“You knew Pa?” Sutter asked.

Callie waited to hear their answer.

“If your pa was Fred Murphy, we did,” Zachariah admitted.

“And that means your brother was Adam Murphy,” Willard said. “We was real sorry to hear about his passing.” He scratched gray hair well receded from his narrow face and glanced around. “A shame he couldn’t make it back before Christmas.”

“Yes, it is,” Callie murmured, eyes feeling hot.

Zachariah reached out a hand and ruffled Frisco’s hair, earning him no better than a frown. “I don’t suppose he sent anything home for his brothers.”

“Not a thing,” Sutter said with a sigh. “And now we have to leave.”

“Leave?” Zachariah turned to Callie. Both of the miners watched her as if she was about to confess she’d been voted president. “Where are you going? North to pan?”

In winter? Oh, but they had the fever bad. “No. We’re going to live with a friend at Wallin Landing. It will be better than this.”

Sutter smashed the pumpkin on his tin plate with a wooden spoon. “Most anything would be better than this.”

Callie couldn’t argue. Adam had been a terrible homesteader. He’d bought them a goat for milk, but the ornery thing had run off weeks ago. Foxes had carried off the chickens. He’d never managed enough money for a horse and plow, so the most they’d been able to grow came from Anna’s vegetable patch behind the house. Callie was just thankful the woods teemed with game and wild fruits and vegetables. But even that bounty was growing scarce as winter approached.

Frisco scooted closer to the table, glanced between the two men. “Sutter and me could come north with you, when you head back.”

Sutter nodded. “We got pans.”

Heat rushed up her. Callie slammed her hands down on the table. “No! No panning, no sluicing. Finish up and head for bed. We have a long way to go in the morning.”

The prospectors had shoveled in the food as if they suspected she was going to snatch it away, then slipped out the back door. And Callie had spent the next hour or so packing up her family’s things, such as they were.

She’d hardly slept that night, but more to make sure her brothers didn’t run off with Zachariah and Willard than with concern over the change she was making. She was glad to see the men gone in the morning, the only sign the holes in the ground where they’d driven their tent pegs. Wearing her brother’s old flannel shirt and trousers, belted around her waist to keep them close, suspenders over her shoulder to keep them up, she’d barely finished feeding Mica mashed pumpkin when Sutter dashed in the door.

“He’s coming!”

Callie’s stomach dipped and rose back up again. So much for not being nervous. Gathering Mica close as she shoved her father’s hat on top of her hair, she followed her brother out onto the slab of rock that served as a front step.

Though he was still dressed in those rough clothes she found hard to credit to a preacher, Levi Wallin had brought two horses with him this time. They were both big and strong, coats a shiny black in the pale sunlight. They were hitched to a long farm wagon with an open bed, the kind Adam had always wanted to buy. Frisco was trotting alongside as if to guide them.

It only took two trips to load their things. Adam had left with his pack, most of the panning supplies and some of the dishes, but she still had her father’s pack and the one Ma had used plus Mica’s wagon. Their belongings fit inside Levi’s wagon with room to spare. She had Sutter bring the quilts their mother had sewn and pile them in a corner of the wagon next to the bench. Pulling on her coat, she glanced around one more time.

This was supposed to be home. Maybe one day she could come back. Maybe no one would want a claim so far out. Maybe she could file for it herself in six months.

Maybe she better leave before tears fell.

Her brothers were already snuggled in the quilts when she came out with Mica in one arm and her rifle in the other. The preacher approached her, and she offered him the baby so she could climb up.

He hesitated, then took the little girl from Callie’s grip. He held her out, feet dangling, as if concerned she might spit on his clothes. Mica bubbled a giggle and wiggled happily.

Callie sighed. “Here, like this.” She lay the rifle on the bench, then repositioned Levi’s arms to better support the baby. Some muscles there—hard and firm. Touching them made her fingers warm. She took a step away from him.

As Mica gazed up at him, the preacher reared back his head, neck stretching, as if distancing himself from the smiling baby in his arms.

“She won’t bite,” Callie told him.

“Yet,” Frisco predicted.

The preacher’s usually charming smile was strained. “It’s been a long time since I held a baby. I was the youngest in my family, and I moved away when my brothers’ oldest children were about this age.”

So that was the problem. Callie patted his arm and offered him a smile. “You’ll do fine. Just hang on to her until I climb up and stow the rifle, then hand her to me.”

That went smoothly enough, until Levi climbed up onto the bench, reins in one fist. His trousers brushed hers as he settled on the narrow seat, and his sleeve rubbed along her arm as he shook the reins and called to the horses. The wagon turned with the team, bringing her and Levi shoulder to shoulder. Each touch sent a tremor through her.