Полная версия

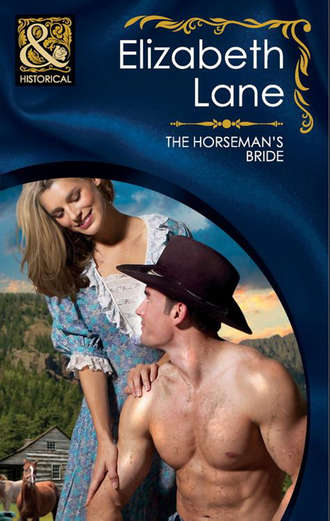

The Horseman's Bride

“Let’s just say I’m not a fool,” she snapped.

“I can see you’re not. And neither is your grandmother. She doesn’t keep that loaded shotgun by the door for nothing. If she thought I had any intention of harming her, I’d be picking buckshot out of my rear.”

“We’ll see about that!” Out of patience, she kneed the colt to a gallop. Tanner didn’t try to follow her, but as she shot across the pasture, Clara became aware of a sound behind her. Even without looking back, she knew what it was.

The wretched man was laughing at her!

Jace watched her ride away, her delicious little rump bouncing in the saddle. Miss Clara Seavers was one sweet little spitfire. He’d enjoyed teasing her, but now it was time to back off and leave her alone. The last thing he needed was that bundle of trouble poking into his past.

Mrs. Mary Gustavson was a fine woman. He would miss her conversation and her cooking. But as soon as he finished the work she needed done it would be time to move on. There would be other towns, other farms, other pretty girls to tease. As long as there was a price on his head, nothing was forever. Not for him. It was keep moving or face his death at the end of a rope.

At least his sister Ruby and her two little girls would be all right.

Hollis Rumford had been considered a fine catch when she’d married him ten years ago. Heir to a farm equipment company, he’d been as charming as he was handsome. But his infidelity, drunkenness and abuse had made Ruby’s life a living hell. Jace had seen the ugly bruises. He had dried his sister’s tears. Lord help him, he wasn’t the least bit sorry Hollis was dead. But he would always be sorry he hadn’t acted sooner. Maybe if he’d taken Ruby and her daughters away from that monster, he’d still have his old life—his friends, his fine apartment in Springfield, his work as a field geologist and engineer and a future in politics that might have taken him all the way to the Missouri Statehouse or the U.S. Congress. Marriage to Eileen Summers, the governor’s niece, would have opened many doors. Now those doors were closed to him forever.

But he hadn’t acted in vain, Jace reminded himself.

Now Ruby would be a respectable widow with a fine house and plenty of money. After a proper mourning period, she’d be free to find a new husband—a decent man, God willing, who’d treat her well and be a good father to her girls.

That had to be worth something, didn’t it?

Clara found her grandmother seated on the porch in her old cane rocker, her hands busy peeling a bucket of potatoes from the root cellar.

“Hello, dear.” Mary Gustavson was tall and raw-boned, her thick white hair swept back from her wrinkled face. Blessed with strong features and cornflower-blue eyes, she looked like an older version of her daughter Hannah, Clara’s mother.

“Good morning, Grandma.” Clara swung off her horse, looped the reins over the hitching rail and bounded up the steps to give the old woman a hug. Mary had raised seven children, buried a husband and baby and worked the farm alone for the past nineteen years. Loss and hard times had burnished her spirit to a serene glow that radiated from her face. Clara and her younger siblings, Daniel and Katy, adored her.

“I was just thinking about you, and here you are.” Even after decades in America, Mary spoke with a lilting Norwegian accent. “Sit down and visit with me awhile.”

“Wait, I’ll help you with those potatoes.” Clara hurried into the house and returned with an extra paring knife. Sitting on the edge of the porch, she picked up a potato. As she sliced off thin strips of peel, she wondered how best to bring up the subject of her grandmother’s new hired man.

“So how is your family?” Mary asked. “Are they all well?”

Clara nodded. “Daniel’s got a girlfriend in town. He’s pestering Papa to let him drive the car so he can take her for a ride.”

Mary chuckled. “I can hardly believe it! It seems like yesterday he was pulling on my apron strings.”

“My pesky little brother is sixteen. I can hardly believe it myself. And Katy, at the wise old age of thirteen, says she’s never going to let a boy kiss her for as long as she lives.”

“Oh, my! That will change in a year or two.”

Clara cut up the peeled potato, dropped it in the kettle and picked up another one. “Not too soon, I hope. Sometimes I think she has the right idea.”

“And what about you?”

Clara glanced up into Mary’s narrowed, knowing eyes. She knew that expression well. Her grandmother had always sensed when something was troubling her. What was she seeing now? Bright eyes? A hot, flushed face?

“I take it you’ve met my new hired man,” Mary said.

Chapter Two

Clara felt the heat rise in her face. If she could feel it, she knew her grandmother could see it. “He’s fixed the pasture fence,” she said. “I very nearly rode Foxfire into the new barbed wire. Whose idea was it to fix that fence anyway? The wire’s been down for years.”

“It was Tanner’s. But when he brought it up, I thought it was a good idea. I’m getting too old to chase your family’s calves out of my garden.”

“Oh, dear! Why didn’t you say something, Grandma? If we’d known about the calves, my dad would’ve fixed that fence a long time ago.”

Mary shrugged. “Judd is a busy man. I didn’t want to bother him about such a little thing. But never mind, it will be fixed now.”

“I suggested to Tanner that he put in a gate. That way we can still cut across the pastures when we come to visit you.”

“Oh? And what did he say to that?”

“He said he’d have to ask the boss.”

“He did, did he?” Mary chuckled as she picked up another potato. “I must say, I like a man who knows his place.”

Clara sighed. This wasn’t going at all well. “Grandma, what possessed you to hire him? He’s a drifter, and you don’t know anything about him. He could be a criminal, waiting for a chance to rob you.”

“Oh? And what would he steal?” Mary’s hands worked deftly as she talked. “The little money I have is safe in the bank. If the man needed food, he’d be welcome to all he could carry. As for the rest, look around you, child. What do I have that’s worth taking? My clothes? My pots and pans? My garden tools?” Her eyes twinkled. “My virtue, heaven forbid? Look at me. I’m an old woman. And whatever else Tanner may be, he’s a gentleman.”

Clara resisted the urge to grind her teeth. The look she’d seen in Tanner’s cobalt eyes was not the look of a gentleman. “What makes you say that?” she asked.

“I offered to let him sleep upstairs, in the boys’ old room. He insisted on laying out his bedroll in the hay shed. Didn’t want folks to gossip, he said.”

Clara groaned inwardly. As if anyone would gossip about her grandmother letting hired help sleep upstairs! Tanner’s excuse had been designed to flatter her and win her confidence. He probably slept outside in case he needed to make a fast getaway. She was becoming less and less inclined to trust the man.

“Why didn’t you tell us you needed help?” she asked. “We could’ve sent a couple of the ranch hands over to do the work. My father would have paid them.”

“I know, dear.” Mary quartered a peeled potato and dropped the pieces into the cooking pot. “But you know I don’t like accepting charity, even from my own family. Tanner needed work, and I …” A smile creased her cheek. “To tell you the truth, I liked the young man right off. And I enjoy his company over supper at night. It’s nice having somebody to talk to.”

Clara forced herself to take a long breath before she spoke. “How long does he plan to be here?”

“We haven’t talked about it. But once he’s made a little money, I expect he’ll move on. He doesn’t strike me as the sort of man to take root in one place.” Mary glanced into the pot. “I believe that’s enough potatoes for now. Give me a minute to put them on the stove, dear. Then we can go on with our visit.”

She pushed forward to rise from her rocker, but Clara had already picked up the pot. She stood, laying her knife on the porch rail. “I’ll do it, Grandma. You stay and rest.”

Swinging through the screen door, she strode into the kitchen. The interior of the house was shabby but comfortable. Mary could have bought new dishes and furniture, but the chipped plates, scarred table and mismatched chairs held precious memories of her husband and children. As Mary was fond of saying, the pieces were old friends and they served her well enough.

In the kitchen, Clara covered the potatoes with water, added a pinch of salt and set the pot on the big black stove to boil. Her grandmother would be waiting outside, but the quiet house held her in its calm embrace, urging her to linger. Savoring the stillness, she wandered into the parlor, where framed photographs of Mary’s family covered most of one wall.

Clara knew them well. Here was Reverend Ephraim Gustavson, her mother’s younger brother who’d gone off to Africa to be a missionary. And here, on the left was a ten-year-old photograph of her own family—her mother, Hannah, and her handsome, serious father, Judd, with their three children. The two younger ones, Daniel and Katy, were almost as fair as their mother. In their midst, Clara looked like a gypsy changeling. But then, her paternal grandfather had been dark. He’d died long before Clara was born, but she’d seen his picture. Tom Seavers had looked a lot like his younger son Quint—Clara’s adored favorite uncle.

Here was Uncle Quint in the photograph taken on his wedding day. He was devilishly handsome with dark chestnut hair, twinkling brown eyes and dimples that matched Clara’s. His bride, Aunt Annie, was Mary’s second daughter. More delicate than her sister Hannah, she had dark blond hair, intelligent gray eyes and a practical disposition that balanced her husband’s impulsive ways.

Clara worshipped her aunt and uncle and looked forward to their rare visits. Never blessed with children, they lived a glamorous life in San Francisco and had traveled all over the world. They always came to the ranch laden with exotic gifts and thrilling stories. On their last visit they’d brought Clara a bolt of white Indian silk, exquisitely embroidered in silver thread. “For your wedding, dear, whenever that might be,” Aunt Annie had told her.

Clara’s mother had put the treasured fabric away for safekeeping, but every now and then Clara would lift the bolt from the cedar chest, touch the silk with her fingertips and wonder if it would ever be used. Many of the girls she’d known from school were already married. But she’d always been more interested in horses than in boys. The idea of pledging herself to a man for the rest of her life had always seemed as far-fetched as walking on the moon. Not that she wasn’t popular. At the town dances, she never lacked for partners. But none of the local boys, even the ones she’d allowed to kiss her, had piqued her interest. They were nice enough, but not one of them had offered a challenge to her way of thinking. In fact, they hadn’t challenged her at all. They had no curiosity, no desire to test the limits of their small, safe lives. On the other hand, a certain blue-eyed hired man …

The sound of muted voices from the front porch yanked her attention back to the present. At first she thought Tanner had come back to talk with Mary. But she was halfway out the door when she realized that the speaker wasn’t Tanner. By then it was too late to reach for Mary’s shotgun.

At the foot of the porch, two grubby-looking men sat bareback astride a drooping piebald horse. The man in front held a cocked. 22 rifle, aimed straight at Mary.

And Tanner was nowhere in sight.

“Go back inside, Clara.” Mary’s voice was low and taut.

“Come on out here, sweetie.” The man in front grinned beneath his greasy bowler hat, showing gummy, tobacco-stained teeth. “Let’s have a look at you.”

Clara walked past Mary as far as the porch railing. She could almost feel the two men eyeing her. She could sense their dirty thoughts, like hands crawling over her body. Her nerves were screaming, but she knew better than to show fear. She kept her head up, her gaze direct.

“That’s a good girl,” the man in the bowler chuckled. “How about unbuttoning that shirt and giving us a show?” When Clara hesitated, his voice lowered to a growl. “Do it, girlie, or the old lady gets it right between the eyes.”

Hands trembling, Clara fumbled with her shirt buttons. The .22 was a small-caliber weapon, mostly good for rabbits and vermin. Hard-core murderers would likely be carrying a more powerful gun. Still, at close range a well-aimed shot could be deadly. She couldn’t take chances with her grandmother’s life.

“Come on, honey, we ain’t got all day. Let’s see them titties.”

Clara’s fingers had unbuttoned the shirt past the top of her light summer union suit. The thin fabric left little to the imagination, but she had no choice except to keep going. Fear clawed at her gut. The men wouldn’t be satisfied with seeing her breasts, she knew. It would be all too easy for one of them to drag her down and rape her while his partner held the gun on Mary.

And then what? Would they murder both women to hide their crime, or maybe just for the pleasure of it? Perhaps the gun was only for show, and they did their real killing with knives or ropes.

Where was Tanner when they needed him?

Her fingers had reached her belt line. The shirt gaped open to the waist. The man with the gun was leering at her. “The underwear, too, missy. Go on, don’t be bashful!”

Clara groped for a shoulder strap. She was dimly aware of the second man, his long legs wrapping the horse’s flanks. He had pale hair and the dull-eyed look of a beast. His tongue licked his full, red lips in anticipation. Her stomach clenched.

“Stop this!” Mary’s voice shook. “Go inside the house. Take whatever you need, but leave my granddaughter alone! She’s an innocent girl!”

“Save your breath, lady. You ain’t the one giving orders. We’ll have our fun with honey pie, here, and take anything we want. And since I get first pick, I’ll be taking this smart little red pony you got tied to the hitching rail. He should make right sweet ridin’. Almost as sweet as—”

“No!” Driven by a blast of rage, Clara sprang between the gunman and her grandmother. One hand snatched up the knife she’d left on the porch railing. Brandishing the blade, she defied the gunman. “Don’t you touch my horse!” she hissed. “If you come near him or my grandmother, so help me, I’ll cut you to bloody ribbons!”

The man’s jaw dropped. For an instant his greasy face reflected shock. Then he grinned. “Why, you feisty little bitch! I’ll show you a thing or—”

“Drop the gun, you bastard!” Tanner’s voice rang with cold authority as he stepped from behind the toolshed. “Drop it and reach for the sky, both of you!”

Tanner had spoken from behind the two men. Now he moved forward to where they could see the .38 revolver in his hand. The .22 thudded to the ground as four hands went up.

“We was only funnin’, mister,” the gunman whined. “We never meant to hurt the ladies.”

“Sure you didn’t.” Tanner pulled back the pistol’s hammer. “The knives, too. Nice and slow. Don’t make any sudden moves and give me an excuse to pull this trigger. I’d shoot you in a heartbeat.”

Rooted to the spot, Clara watched the men draw their hunting knives and toss them to the gravel. Mary had risen and slipped into the house. She emerged with the shotgun cocked and aimed at the two desperados.

“I’ve got your back, Tanner,” she said. “Say the word and I’ll blow them to kingdom come.”

“I knew I could count on you.” Tanner’s grin flashed. Then for the first time, he seemed to notice Clara. “When you get yourself together, Miss Clara, maybe you could get down here and gather up their weapons.”

Cheeks blazing, Clara put down the paring knife and fumbled with her buttons. She must have looked like a fool, standing there with her chest exposed, brandishing that pathetic little blade. Behind that sneer, Tanner was probably laughing his head off.

“What should we do with these two buzzards, Mary? Do you want me to shoot them for you?” Tanner seemed to be playing with the two men, trying to make them squirm.

“That’s tempting,” Mary replied. “But I suppose the right thing would be to lock them in the granary and telephone for the marshal.”

Clara had come down off the porch, close enough for her to see the twitch of a muscle in Tanner’s cheek as he hesitated. What if he didn’t want Mary to call in the law? What if he was worried about being seen?

Still pondering, she moved to the far side of the horse and bent to pick up the gun and the two knives. That was when she saw the flicker of movement. The dull-eyed man who sat in the rear had slipped a thin-bladed knife out of his boot.

“No!” she screamed, but it was too late. The man’s supple hand moved with the speed of a striking rattlesnake. The knife sliced the air, sinking hilt-deep into Tanner’s right shoulder.

A curse exploded between Tanner’s lips. His gun hand sagged. The man in front yanked the reins and the piebald reared and wheeled, its hoof grazing Clara’s head. Clara reeled backward, lost her balance and went down rolling to avoid being trampled.

The shotgun roared behind the fleeing outlaws. But Mary had fired high. The blast went over their heads as the horse thundered down the drive toward the main road with the two men clinging to its back.

Still dazed, Clara struggled to her feet. Mary had collapsed in the rocker with the shotgun across her knees. Tanner had lowered the pistol. His face was ashen. His torn sleeve oozed crimson where the knife handle jutted out of his shoulder.

Clara could feel a throbbing lump at her hairline where the iron shoe had grazed her skull. A wet trickle threaded its way down her temple.

Mary laid the shotgun on the porch and rose shakily to her feet. “We’ll need some wrappings,” she said. “I’ll get something we can tear into strips. Meanwhile, Clara, you’d better help this fellow to the porch before he takes a header. Don’t try to take the knife out until we’ve got something to stop the blood.”

“I’ll be all right.” Tanner spoke through clenched teeth, swaying a little as he staggered toward the steps. Clara darted to his side and braced herself against his left arm. His body was warm and damp, the muscles rock hard through the worn chambray shirt. She felt the contact as a shimmering current of heat.

Mary paused at the door. “I suppose we should call the marshal. He’ll want to pick up their weapons and question us about what happened.”

Clara felt Tanner’s body tighten against her, felt his hesitation. “Why bother?” he asked. “In the time it takes the marshal to get here, those ruffians could be halfway to the next county.”

“But what if they try to rob somebody else?”

“They’re unarmed, Mary. And they know we can identify them. Trust me, all they’ll want to do is hightail it out of here, as far away as they can get.”

Beside him, Clara studied the chiseled profile, the narrowed eyes and tense jaw. Where she stood against his side, she could feel the pounding of his heart. If her grandmother called the marshal, she sensed Tanner would slip away and be gone—along with his beautiful stallion, and a wound that could be fatal if left untreated.

He had just rescued them, possibly saving their lives. Would it be so wrong to keep him here a little longer?

“Tanner’s right, Grandma,” she said. “Once those men are outside the marshal’s jurisdiction, there’s nothing he can do. Why waste his time?”

His eyes flashed toward her, caught her gaze and held it. In those fathomless blue depths she read gratitude, suspicion and a world of questions.

Mary sighed. “Oh, that makes sense, I suppose. But I hate the thought of that awful pair getting away. I’d have aimed lower but I didn’t want to hit that poor horse.” She opened the screen door and hurried into the house.

Clara supported Tanner as they covered the short distance toward the porch. “You don’t need to hold me up,” he muttered. “My legs are fine.”

“Don’t be so proud!” she scolded him. “You’re in shock. You look as if you could pass out any second, and you’re about to drop that pistol.” She took the heavy .38, which was barely dangling from his fingers. “Here, sit on the steps. I’ll get you something to drink.”

“I’m guessing there’s no whiskey.” He sank onto the middle step with a grunt of pain. His left hand clutched his right arm, the fingers tight below the wound.

“My grandmother does keep a little—strictly for medicinal purposes. Will you be all right while I get it?”

“Just get the blasted whiskey!”

“Hang on.” She dashed into the house, letting the screen door slam shut behind her.

Only after she’d gone did Jace give vent to the pain that pooled like molten lead around the knife in his shoulder. A string of obscenities purpled the air. If nothing else, the muttered oaths braced his courage. The wound itself didn’t appear that serious, but if that blade was as filthy as the bastard who’d thrown it, he could be in danger of blood poisoning.

The girl had surprised him, standing there like a defiant little cat pitted against a pair of mongrel curs. He’d been in the woodshed looking for gate timbers when the two ruffians appeared. It had taken him precious minutes to circle around and retrieve the pistol he’d hidden in his bedroll. He’d returned to find her with her shirt gaping open as she threatened two armed criminals with that silly little paring knife.

His mouth had gone dry at the sight of her.

He’d be smart to banish the image from his mind, Jace lectured himself. Clara Seavers was a lady. Her courage and fighting spirit merited his respect. But the memory of her standing there on the porch, her proud little breasts straining against the wispy fabric that covered them, would fuel his erotic dreams for nights to come.

Damn!

He shifted his weight on the step. The movement shot pain all the way down to his fingertips. Biting back a moan, he focused his gaze on the circling flight of a red-tailed hawk. Beyond the pasture, where the road stretched into open country, the two intruders had long since vanished from sight.

What would have happened if he hadn’t been here? The thought sent a dark chill down his spine. He found himself wanting to catch up with the miscreants and rip them limb from limb. If either of them had so much as laid a hand on her …

Jace shook his head, silently cursing his own helplessness. He should be counting his blessings that the idiots had gotten away. If he and Mary had been able to hold them, the marshal would have been called in, and he’d have found himself dragged to jail along with them. Even now, he had to wonder if the men, if apprehended, would be able to identify him. Now would be the smart time to climb on his horse and ride away. But he was in no condition to go anywhere.

Why had Clara backed his argument against calling the marshal? Was she just talking common sense, or had those big sarsaparilla eyes seen through his facade to the fugitive he was? And if she suspected the truth, why had she helped him? Was it some kind of trick, meant to lull him into a false sense of security?

Were the women calling in the law even as he waited?

Jace’s hands had clenched into fists. Slowly he forced his fingers to relax, forced his mind away from the searing pain in his shoulder. Damn it, where was that whiskey? His ears strained for the patter of Clara’s light footsteps crossing the floor. He remembered the cool touch of her fingers, the pressure of her body against his side. He could feel himself swaying, getting light-headed. The pain was intoxicating. Maybe he should just grab the knife, yank it out and try to get to his horse. His hand crept toward knife handle.

“No!”

She was here now, rushing across the porch with Mary on her heels. As the screen door slammed shut, she dropped to her knees beside him. One hand clutched a pillow. The other clasped a bottle of cheap whiskey. “Give me that,” he growled, reaching to twist it out of her hand.