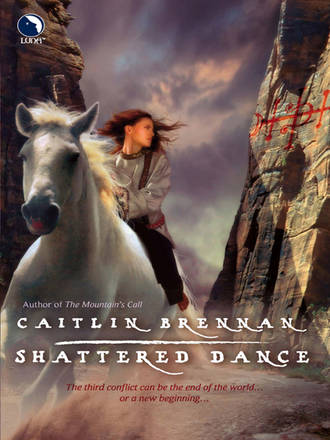

Полная версия

Shattered Dance

He would have to reach her somehow. A letter would be too slow. He did not have the rank or station, let alone the coin, to send a courier all the way to the Mountain.

He would find a way. Then she would tell him what to do. Valeria always knew what to do—or else her stallion did. He was a god, after all.

Maurus set off down the street as if he had every right to be there. Vincentius, who was much taller, still had to stretch to keep up. By the time they reached the turning onto the wider street, where people were up and about in the bright summer morning, Maurus felt almost like himself again.

Chapter Seven

The school on the Mountain was in a flurry. For the second time since Valeria came to it, the best of its riders and the most powerful of its stallions were leaving its sanctuary and riding to the imperial city.

That was a rare occurrence. Considering how badly the last such riding had ended, it was no wonder the mood in the school was complicated to say the least. Nor did it help that by ancient tradition the coronation must take place on the day of Midsummer—and therefore the strongest riders and the most powerful stallions would not be on the Mountain when this year’s Called were gathered and tested.

They had to go. One of their most sacred duties was to Dance the fate of a new emperor or empress. They could no more refuse than they could abandon the stallions on whom their magic depended.

And yet what passed for wisdom would have kept them walled up on the Mountain, protected against any assault. Nothing could touch them here. The gods themselves would see to that.

The Master had settled on a compromise. Half of the First Riders and most of the Second and all of the Third and Fourth Riders would stay in the school. Sixteen First and Second Riders and sixteen stallions would go to Aurelia.

Valeria went as servant and student for the journey. Then in Aurelia she would stay after the Dance was done, under Kerrec’s command.

They were going to try something new and possibly dangerous. But Kerrec had convinced the Master that it might save them all.

He was going to extend the school to Aurelia and bring a part of it away from the fabled isolation of the Mountain into the heart of the empire. If their magic could stand the glare of day and the tumult of crowds, it might have a chance to continue, maybe even to grow.

It needed to do that. It was stiffening into immobility where it was.

In the world outside its sanctuary, all too many people had decided the horse magic had no purpose. Augurs could read omens without the need to study the patterns of a troupe of horsemen riding on sand. Soothsayers could foretell the future, and who knew? Maybe one or more orders of mages could try to shape that future, once the riders let go their stranglehold on that branch of magic.

Valeria happened to be studying the patterns of sun and shadow on the floor of her room as she reflected on time, fate and the future of the school she had fought so hard to join. The only sound was the baby’s sucking and an occasional soft gurgle.

The nurse sat by the window. Her smooth dark head bent over the small black-curled one. Her expression was soft, her eyelids lowered.

Valeria’s own breasts had finally stopped aching. After the first day there had never been enough milk for the baby, but what feeble trickle there was had persistently refused to dry up.

However much she loathed to do it, she had had to admit that her mother was right. She needed the nurse.

The woman was quiet at least. She never hinted with face or movement that she thought Valeria was a failure. She did not offer sympathy, either, or any sign of pity.

“It’s nature’s way,” Morag had said by the third day after Grania was born. The baby would not stop crying. When she tried to suck, she only screamed the louder. Yet again, the nurse had had to take her and feed her, because Valeria’s milk was not enough.

“Sometimes it happens,” Morag said. “You see it with mares, too, in the first foaling, and heifers and young ewes. They deliver the young well enough, but their bodies don’t stretch to feeding it. You’d put a foal or a calf with a nurse. What’s so terrible about doing it with a baby?”

“I should be able to,” Valeria said, all but spitting the words. “There’s nothing wrong with me. You said. The Healers said. I shouldn’t be this way!”

“But you are,” her mother said bluntly. “Stop fighting it, girl, and live with it. There’s plenty of mothering to do outside of keeping her belly filled.”

“Not at the moment there isn’t,” Valeria said through clenched teeth.

“Certainly there is,” said Morag. “Now give yourself a rest while she eats. You’re still weak, though you think you can hide it.”

Valeria had snarled at her, but there was never any use in resisting Morag. The one time she had succeeded, she had had the Mountain’s Call to strengthen her.

The call of mother to child was not as strong as that—however hard it was to accept. She had bound her aching breasts and taken the medicines her mother fed her, and day by day she had got her strength back.

Now, almost a month after Grania was born, Valeria was nearly herself again. She had even been allowed to ride, though Morag had ordered her to keep it slow and not try any leaps. She might have done it regardless, just to spite her mother, but none of the stallions would hear of it.

They were worse than Morag. They carried her as if she were made of glass, and smoothed their paces so flawlessly that she was ready to scream.

“I like the big, booming gaits!” she had shouted at Sabata one thoroughly exasperating morning. “Stop creeping about. It’s making me crazy. I keep wanting to get behind you and push.”

Time was when Sabata would have bucked her off for saying such things. But he barely hunched his back. He did, mercifully, stretch his stride a little.

It was better than nothing. After a while even he grew tired of that and relaxed into something much closer to his normal paces. Valeria was distressed by how hard she had to work to manage those. Childbearing wrought havoc with a woman’s riding muscles.

On this clear summer morning, several days after her outburst to Sabata, she was done picking at her breakfast. Grania was still engrossed in hers.

It was hard to rouse herself to leave them, but each day it grew a little easier. The stallions were waiting. There were belongings to pack and affairs to settle. Tomorrow they would leave for Aurelia.

Today Valeria had morning exercises to get through, classes to learn and teach and the latest arrival of the Called to greet. Last year’s flood of candidates had not repeated itself. So far this year, the numbers were much more ordinary and the candidates likewise. None of them was already a mage of another order, and they were all boys, with no grown men taken unawares by the Call.

She was glad. This was not the year to tax the riders with more of the Called than they had ever seen before.

She should get up and go. But the sun was warm and its patterns on the floor were strangely fascinating. She had been studying the art of patterns, learning to see both meaning and randomness in the veining of a leaf, and significance in sunlight.

Riders were mages of patterns more than anything, even more than they were both masters and servants of the gods who wore the forms of white horses. The pattern she saw here was exquisitely random. Shadows from the leading of the window divided squares and diamonds of sudden light.

The different shapes blurred. Valeria blinked to clear her sight. The oddness grew even worse.

It did not look like sunlight on a wooden floor any longer but like mist on water with sunlight behind it. As she peered, a figure took shape.

She had played at scrying when she was younger, before she came to the Mountain. A mage filled a cup of polished metal—silver if she could find it, tin or bronze if not—and turned it so that the light fell on but not in it. Then if one had the gift, visions came.

Valeria had never seen anything she could use. She was not a seer. That magic had passed her by.

And yet this pattern on the floor made her think quite clearly of scrying in a bowl. There was a face staring at her out of the mist, young and worried and startlingly familiar. It brought the memory of last summer in Aurelia before Kerrec ran away to the war, when six young nobles had come to Rider’s Hall to learn to ride like horse mages.

Maurus was the first who had come, along with his cousin Vincentius. He had been one of the better pupils, too. In time he might make a rider, though he had no call to the school on the Mountain.

He was staring at her with such a combination of recognition and relief that she wondered what had made him so desperate.

If she had fallen into a dream, it felt amazingly real. She heard Maurus’ voice at a slight distance, as if he were calling to her down the length of a noble’s hall, but the words were clear. “Valeria! Thank the gods. I didn’t know if this would work. Pelagius promised it would, but he’s only a seer-candidate, and I wasn’t sure—”

His head jerked. It looked as if someone had shaken him. When he stopped shaking, his words came slower and stopped sooner. “I’m sorry. I didn’t mean to babble. I couldn’t think who else to talk to, and I was afraid you weren’t coming to the coronation Dance. You are coming, aren’t you?”

“I do intend to,” Valeria said.

“Good,” he said. “That’s good. I hope you get here in time.”

“Why?” said Valeria. Her stomach knotted. It was not surprise, she noticed. It felt like something she had not even known she was expecting. “What’s wrong?”

“Pelagius says I can show you,” Maurus said, “but you have to help. It’s pattern magic, he says. You have to bind it to my face and voice, then you’ll see it.”

Maurus did not sound as if he knew what he was saying. Somehow that convinced Valeria that she was not dreaming. This really was the boy from Aurelia, and he really had reached her through a scrying spell.

However fond Maurus might be of his own voice, he was not a frivolous person. If he had gone to such lengths to convey this message to her, it must be urgent.

It could be a trap. Both the empire and the Mountain had powerful enemies, and Valeria had attracted her fair share of those. She would not put it past one of them to bait her with this child and then use the spell to destroy her.

She could smell no stink of betrayal in either Maurus or the working that had brought his consciousness here. What he asked of her, she could do. It was a simple magic, taking the patterns of the message and opening them into a whole world of awareness.

There were rough edges in this working, raw spots that told her the mage who wrought it was no master. She had to be careful or her own patterns would fall apart, trapping her inside the spell.

It had been easier when she did it in the schoolroom with First Rider Gunnar steadying her. She had to be the steady one here.

She bound her consciousness to each thread of the pattern that Maurus had brought with him. When she had every one in her control, she turned her focus on the center and willed it to open.

It burst upon her in a rush of sensation. She saw and heard and felt and even smelled the dark room, the altar, the circle, the creature they conjured out of nothingness. The words they spoke buried themselves in her consciousness.

As abruptly as the vision had come, it vanished. Maurus stared at her from his puddle of sunlight. He was dimming around the edges and his voice was faint. “Valeria? Did you get it?”

“I have it,” Valeria said.

“What should we do? Do you know what it is? Do you think you can stop it?”

“I don’t know yet,” Valeria said, trying not to be sharp. “I have to think about it. I’ll do what I can—that much I promise.”

Maurus sighed. She barely heard the sound. “I trust you,” he said, “but whatever you do, I hope you can do it quickly. I don’t think there’s much time.”

“I’ll try,” she said. “We’ll be in Aurelia in a fortnight. If something threatens to happen before then, go to the empress and show her what you showed me. Don’t be afraid—and don’t hesitate. Tell her I sent you.”

Maurus’ mouth moved, but Valeria could not hear what he said. The light was fading. The working was losing strength.

Before she could ask him to speak louder, he was gone. An empty pattern of sun and shadow dappled the floor. Grania was asleep in her nurse’s arms, and Valeria was unconscionably late for morning exercises.

Chapter Eight

Valeria went through the morning in a daze. It seemed no one noticed but the stallions—and they did not remark on it. Their mortal servants were distracted by the preparations for the riders’ departure.

She did not remember what she taught the rider-candidates in her charge, except that none of them suffered loss of life or limb. Her own lessons passed in a blur.

For those who were traveling to Aurelia in the morning, there were no afternoon lessons or exercises. They were to spend the time packing their belongings and seeing to it that the stallions were ready for the journey.

Maurus’ message changed nothing. She was still leaving tomorrow. That battle was long since fought and won, and she had no intention of surrendering after all.

The baby was old enough to travel. The nurse would help to look after her, and Morag was riding with them as far as the village of Imbria. Grania would be nearly as safe on the road as she was on the Mountain.

It was by no means a surprise that a faction of nobles was plotting against the empire. That was all too commonplace. But that Maurus should have come to Valeria in such desperation and nearly inarticulate fear, made her deeply uneasy.

It was not like Maurus to be so afraid. He was a lighthearted sort, though not particularly light-minded. Very little truly disturbed him.

This had shaken him profoundly. It was dark magic beyond a doubt, and what it had conjured up was dangerous.

The barbarian tribes were Aurelia’s most bitter enemies. They lived to kill and conquer, and they had waged long war against the empire’s borders. Their warriors worshipped blood and torment. Their priests were masters of pain.

If a conspiracy of nobles had summoned one of those priests to the imperial city, that could only mean that they meant to disrupt the coronation. They would strike at the empress, and they well might try to break the Dance again.

Valeria could not believe that the empress was unaware of the threat. Neither Briana nor her counselors were fools. Both coronation and Dance would be heavily warded, with every step watched and every moment guarded. What could a single priest of the One do against that, even with a cabal of nobles behind him?

Valeria had been walking to the dining hall for the noon meal, but when she looked up, she had gone on past it down the passage to the stallions’ stable. She started to turn but decided to go on. She was not hungry, not really. Maurus’ message and the vision he had sent had taken her appetite away.

She rounded a corner just as Kerrec strode around it from the opposite direction. She had an instant to realize that he was there. The next, she ran headlong into him.

He caught her before she sent them both sprawling, swung her up and set her briskly on her feet. She stood breathing hard, staring at him. She felt as if she had not seen him in years—though they had shared a bed last night and got up together this morning.

They had not done more than lie in one another’s arms since Grania was born. That was all Valeria had wanted, and Kerrec never importuned. He was not that kind of man.

Just now she wished he were. It was a sharp sensation, half like a knife in the gut, half like a melting inside. When winter broke on the Mountain and the first streams of snow-cold water ran down the rocks, it must feel the same.

She reached for him and found him reaching in turn, with hunger that was the match of hers exactly.

How could she have forgotten this? Having a baby turned a woman’s wits to fog, but Valeria had thought better of herself than that.

It seemed she was mortal after all. She closed her eyes and let the kiss warm her down to her center. The taste, the smell of him made her dizzy.

They fit so well into each other’s empty places. She arched against him, but even as he drew back slightly, she came somewhat to her senses. This was hardly the place to throw him down flat and have her will of him.

She opened her eyes. His were as dark as they ever were, more grey than silver. He was smiling with a touch of ruefulness. “It’s been a little while,” he said.

“Too long,” said Valeria.

“We can wait a few hours longer,” he said.

She trailed her fingers across his lips. That almost broke her resolve even as it swayed his, but she brought herself to order. So, with visible effort, did he. “What is it? Is there trouble? Is it Grania?”

That brought her firmly back to her senses. “Not Grania,” she said, “or anyone else here.”

His brows lifted at the way she had phrased that. He reached for her hand as she reached for his. By common and unspoken consent, they turned back the way he had come.

The stalls were empty. All the stallions were in the paddocks or at exercises. The stable was dim and quiet.

The stallions’ gear was packed and ready to travel. The boxes of trappings for the Dance stood by the door, locked and bound, and the traveling saddles were cleaned and polished on their racks. She blew a fleck of dust from Sabata’s saddle and ran a finger over one of the rings of his bit. It gleamed at her, scrupulously bright.

Kerrec did not press her. That was one of the things she loved most about him. He could wait until she was ready to speak.

He would not force her, either, if she decided not to say anything. But this was too enormous to keep inside. She gave it to him as Maurus had given it to her, without word or warning.

It said a great deal for his strength that he barely swayed under the onslaught. After the first shock, he stood steady and took it in. He did not stop or interrupt it until it was done. Then he stood silent, letting it unwind again behind the silver stillness of his eyes.

Valeria waited as he had, though with less monumental patience. He was a master. She was not even a journeyman. She was still inclined to fidget.

After a long while he said, “The boy would have been wiser to go to my sister.”

“He didn’t think it worthwhile to try,” Valeria said. “She’s the empress, after all. He’ll never get through all her guards and mages.”

“Someone should,” Kerrec said. “They’ve conjured a priest of the barbarians’ god—and from what the boy saw of him, he’s even worse than the usual run of them. We’re weaker than we were when his kind broke the Dance. My sister’s hold on court and council is still tenuous. Even forewarned and forearmed, she’s more vulnerable than my father was. She’s all too clear a target.”

“I’m sure she knows that,” Valeria said. “Can you relay this message to her?”

“I can try,” he said, “but she’s warded by mages of every order in Aurelia. I’m strong, but I’m not that strong.”

“You are if you ask the stallions to help.”

He arched a brow at her. “I? Why not you?”

“You’re her brother,” Valeria said, “and much more skilled in this kind of magic than I am. I’m just learning it. It’s not so hard face to face, but across so much distance…what if I fail?”

“I doubt you would,” Kerrec said, “with the stallions behind you.”

“You’re still better at it,” she said.

He pondered that for a moment before he said, “I’ll do it.”

“Here? Now?”

“When I’m ready.”

The urgency in her wanted to protest, but she had laid this on him. She could hardly object to the way he chose to do it.

He smiled, all too well aware of her thoughts. His finger brushed her cheek. “It won’t be more than a few hours,” he said.

“That’s what you said about us.”

He had the grace not to laugh at her. “Before that, then.”

That did not satisfy her. “What if those few hours make the difference?”

“They won’t,” he said. “I can feel the patterns beginning to shift, but they won’t break tonight. It takes time to do what I think they’re going to try. They’ll need more than a day or two to set it in motion.”

“What—how can you know—”

“If you know where to look, you can see.”

She scowled at him. Sometimes he forced her to remember that he was more than a horse mage. He had been born to rule this empire, but the Call had come instead and taken him away.

Kerrec had died to that part of himself—with precious little regret. Then his father had died in truth and given him the gift that each emperor gave his successor. All the magic of Aurelia had come to fill him.

It had healed Kerrec’s wounds and restored the full measure of his magic. It had also made him intensely aware of the land and its people.

His sister Briana had it, too. For her it was the inevitable consequence of the emperor’s death. She was the heir. The land and its magic belonged to her.

It was not something that needed to be divided or diminished in order to be shared. The emperor had meant it for both reconciliation and healing, but maybe it was more than that. Maybe Artorius had foreseen that the empire would need both his children.

Kerrec seemed wrapped in a deep calm. His kiss was light but potent, like the passage of a flame. “Soon,” he said.

Voices erupted outside. Hooves thudded on the sand of the stableyard. Riders were bringing stallions in to be groomed and saddled for afternoon exercises.

Valeria stepped back quickly. There was no need for guilt—if everyone had not already known what was happening, Grania would have been fairly strong proof. But it had been too long. She was out of practice.

Kerrec laughed at her, but he did not try to stop her. She was halfway down the aisle by the time the foremost rider slid back the door and let the sun into the stable.

Kerrec was more troubled than he wanted Valeria to know. He would have liked to shake the boy who, instead of taking what he knew to the empress like a sensible citizen, reached all the way to the Mountain and inflicted his anxieties on Valeria. Was there no one closer at hand to vex with them?

That could be a trap in itself. Valeria was notorious among mages. She was the first woman ever to be Called to the Mountain and a bitter enemy of Aurelia’s enemies. She had twice thwarted assaults on the empire and its rulers. In certain quarters she was well hated.

Kerrec was even less beloved, though the brother who had hated him beyond reason or sanity was dead, destroyed by his own magic. There were still men enough, both imperial and barbarian, who would gladly have seen Kerrec dead or worse.

This kind of thinking was best done in the back of the mind, from the back of a horse. He saddled one of the young stallions, a spirited but gentle soul named Alea.

The horse was more than pleased to be led into one of the lesser courts, where no one else happened to be riding at that hour. Kerrec had been of two minds as to whether to bring the stallion with him to Aurelia, but as he smoothed the mane on the heavy arched neck, he caught a distinct air of wistfulness. Alea wanted to see the world beyond the Mountain.

“So you shall,” Kerrec said with sudden decision. He gathered the reins and sprang into the saddle, settling lightly on the broad back.

Alea was young—he had come down off the Mountain two years before, in the same herd that had bred Valeria’s fiery Sabata—and although he was talented, he had much to learn before he mastered his art. Kerrec took a deep and simple pleasure in these uncomplicated exercises. They soothed his spirit and concentrated his mind.