Полная версия

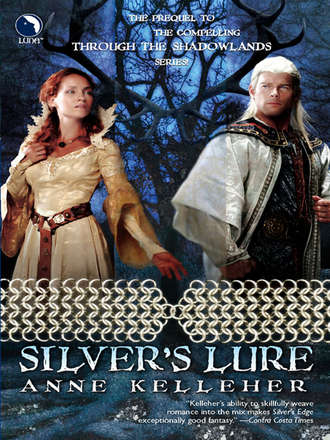

Silver's Lure

There was a lambent energy surging through the air like a barely audible hum. The sound of horns was fading but the scent of Shadow lingered and she wondered what brought her father out to hunt. The sidhe didn’t hunt at night. It was far too dangerous, for at night, the goblins crept out of their lairs below the Forest. They themselves were disobeying by leaving their bowers at night.

She sniffed, delicately sorting through all the competing scents twining through the Forest. There he was, she thought, catching the barest whiff of the boy, ripe as a sun-warmed acorn. She closed her eyes and inhaled, pulling as much of his essence, of his scent, as far and as deep into herself as she could, until she was certain she could find him again. He made her palms tingle and her toes curl.

“Let’s go after them—” Tatiana’s hot breath in her ear made Loriana jump. They pressed against her, their bodies damp and cool, and Loriana could feel the need the mortals had roused.

“There was something strange about him,” said Chrysaliss as she wrapped an arm around Loriana’s waist and combed her fingers through Loriana’s wet hair, twining the silky strands around her fingers into long curls. “Don’t you think he smelled strange?”

“He didn’t smell strange. He smelled young,” Loriana whispered. It was already too late to follow, for she could read his essence fading even now, as the breeze dispersed what was left of him in Faerie into the wind.

“Young…” Tatiana drew a deep breath and closed her eyes, leaning her head back into Loriana’s shoulder, wearing a wide smile as she savored the last of the boy’s scent.

“I’d prefer the other,” said Chrysaliss. “The other one—didn’t you see him? The one who told the young one to ride?” In the fading dusk, her teeth were very white as she smiled and her eyes were very green. “Do you know who he is? I’ve seen him on this side of the border more than once or twice—he’s the first I’d pick at night, too.” The two collapsed on each other in gales of giggles.

Loriana looked up and frowned. The leaves on the trees were quivering and the throb in the air was more palpable. Beneath the branches, the dark pools of shadows began to grow around the trunks. Their bath had been fun, but now it was spoiled somehow and she felt not the slightest desire to get back into the water. “I think we should go home.”

“Why?” Tatiana waded out into the center of the water and peered down into the shallow depths. “You know, if the moon would just rise a bit, I think we could—”

“Tatiana, come back.” Loriana grabbed Chrysaliss by the wrist, as if to prevent her from doing the same. “Come, let’s get out of the water. I think we should go now.”

“But why?” Tatiana flung a few drops of water at them both and grinned. “This stream cuts straight through Shadow. We can follow him, we can find him—and the other one, too. Come, what’s the harm?”

Beneath Loriana’s feet, the ground gave a palpable throb. “What’s that?” asked Chrysaliss, looking down. The throb was growing stronger.

Loriana looked up. The leaves shook visibly and the subtle throb had turned into an audible pulse. “It’s drums,” she whispered. “Goblin drums and they’re not just getting louder, they’re getting closer.”

As if she’d given a signal, a hideous cacophony erupted from somewhere far too close. Chrysaliss wrapped her arms around Loriana, and Tatiana, galvanized, came running out of the water.

The pounding was growing louder. Loriana grabbed for Tatiana’s hand and the three clung to each other. “Which way are they coming?” breathed Tatiana, as they backed up close to the largest of the nearest trees.

The sound was all around them now, shuddering through the ground, rending the air, and Loriana pressed her back against the tree. Up. The word filled her mind with urgency and Loriana looked up. The branches above their heads were bending down. “We have to go up,” Loriana answered as the ground began to quake beneath their feet.

“They’re coming this way,” Loriana said. She reached up, into the welcome of the tree, felt the branch twist itself beneath her hands. The other girls scrambled beside her just as the leading edge of the horde ran across the stream.

The screeches and the screams, the trills and the yelps were all part of some discordant language, she realized, but the drums, so wild and so loud, were disorienting as they filled the air.

“Wait—I’m fall—” cried Tatiana, and she did, slipping off the branch and tumbling to the ground below. She landed with a thump, and as Loriana gazed down in horror, Tatiana was caught up by the goblins. With shrieks of glee at their unexpected prize, they dragged her into their midst, tossing her from one to the other as they ran through the trees.

Her screams faded as the horde swept by. “What should we do?” Chrysaliss whispered.

“Stay here,” Loriana whispered back. The goblins were galloping under the trees now, scrambling like drunken mortals, heady with the noise and the scents. “We’re just going to stay here. And hope they go away.”

“Or that someone finds us.” As if in reassurance, Loriana heard faint, frantic blasts of the horns. “Hear that? Father’s coming.” She squeezed Chrysaliss tight, and the two clung to each other and the trunk of the tree. Loriana pressed her cheek against the papery bark of the ancient birch. But the goblins weren’t going away. They roamed back and forth beneath the trees, pausing every now and then to sniff and peer.

“What’re they doing?” muttered Chrysaliss. “Why don’t they go away?”

“It’s like they’re…like they’re looking for something,” Loriana breathed back. The horns sounded louder, and in the far depths of the wood, Loriana thought she saw distant flashes of the sidhe’s lych-spears. “Or someone.”

“What if they look up?” Chrysaliss whispered. “We should go higher.”

Loriana froze. Like her mother, she despised heights. Beside the squat old birch, its boughs interlaced, a graceful ash soared high.

“Come on,” Chrysaliss was tugging at her, pulling her off the birch and onto the ash. “Come, we have to get higher—higher where they won’t see us—” A clawed hand snaked around her ankle and yanked her down. She disappeared below with a high-pitched scream.

Gasping, Loriana bolted. Across the limbs, light as a wisp, she darted, dashing from branch to branch, following the line of the river that carried her, against all instinct, away from the Forest House. But the horns were louder now, the goblin drums less insistent. She paused to catch her breath in a hollow of a bending willow. The goblin roars were louder, if possible, but she heard the battle trills of the warriors, saw the flashes of light zigzag across the sky like summer lightning. They were fighting somewhere very close, she thought. She curled up as tightly as she could within the hollow, her arms wrapped around her knees, her face tucked down. The sound of her friends’ screaming echoed over and over, and she trembled, bit her lip and tried to stop shaking.

But the smell of burning and wafting smoke choked her and, peering cautiously out, she looked around in all directions. Another noise was rising on the wind, a noise only the sidhe and the trees could hear. It was the screaming of a living tree on fire. Loriana’s gut twisted and nausea rose in the back of her throat. She staggered, clinging to the trunk of the nearest tree, and felt the pain resonate underneath her hand. They all shared it to some degree; they all felt it. And then someone stepped around a tree, a tall figure, pale as a goblin in the sun, carrying what appeared to be something limp and dead.

At first she thought the figure was her father. But it can’t be Father, she thought. But the figure had his walk, his stance, his set of shoulders. Not his hair, for Auberon’s was as copper as her own, and this man’s feathered around his face in coal-black waves, reflecting blue glints in the moonlight. He was mostly naked, but for a pair of torn boots and ragged trews of the kind the mortals wore, and she wondered why he didn’t come up into the trees out of harm’s way like any reasonable sidhe. Intrigued, she watched him as he passed beneath the willow. Swift as a cat she uncurled herself and crept silently just behind him.

He paused, looked up, and seemed to sense her presence. She darted around the trunk as he hoisted himself into the tree. He turned one way, then another, and their eyes met. In the dark, she saw the green gleam of his. “Who’re you?” she whispered.

“I’m Timias,” he replied, and the name made her eyes widen.

This is Timias? Raised by her grandfather, King Allemande, beside her father Auberon, after his own family was slaughtered, Timias was hardly mentioned by anyone at Court, he’d been gone so long. She’d been still a child when he left. He looked like a pale imitation of her father in the starlight.

“Who’re you?”

She opened her mouth to answer, when violent movement in the trees behind him caught her eye. She gasped and pointed over his shoulder as the biggest goblin she had ever seen burst through the trees, running, it seemed, directly at them both.

Timias grabbed her wrist and pulled her up higher into the tree, but not before the goblin spotted them. As the goblin leaped for them both, Loriana saw her mother and a dozen or more mounted sidhe come riding into the clearing. As the sidhe raised their weapons, Loriana clung to Timias’s hand. “What is that thing?”

“That’s Macha, their queen,” he answered. “The sidhe have a king—the goblins have a queen.”

The enormous queen reared up and around, dwarfing the warriors on their dainty white horses.

“And that’s my mother,” Loriana said. She tried to see past him but he wouldn’t let her.

“We have to run,” he said. “Now!”

He dragged Loriana stumbling and weeping through the trees. At last he paused. “I’m sorry if I hurt you.”

“That was my mother,” she whispered, wiping her face. “Leading the warriors, that was my mother.”

She heard the soft intake of his breath. For a long moment, they sat in silence in the dark. Then he said, “You’re Auberon’s daughter, aren’t you?”

She raised her eyes to his. He was staring at her almost the way a goblin would and for a moment she felt a prickle of fear. Don’t be silly, she told herself. He saved your life. “Yes,” she said. “I’m Loriana.”

She expected him to say something, but he ducked his head and said, “We can go lower now, I think.”

Instinctively, she clung to his hand. The palm was wet, the skin was fleshy, but he held her strongly, firmly and she was comforted enough to let him lead her. She could see the lights, hear the shouts of the Court.

“What were you doing out there?” Timias was asking her.

Her lower lip trembled as she looked up at him. “We were bathing,” she said.

“Did no one warn you to stay out of the wood?”

“Of course they did,” said Loriana. “The wood, not the bathing pool by the river.”

He took her by the elbow and pointed. “Look—we cross that stream, we’re there.”

She took a deep breath, forcing herself to follow his voice, to cling to his hand. Her grandmother had nothing good to say of Timias, her father spoke of him seldom if at all. But he’d come back just at the right moment. She thought of her mother and her friends and the other warriors and tears filled her eyes. She followed him blindly, and stumbled against him, not realizing that he’d stopped, for no apparent reason, in the middle of the path.

“What is it—” she began as she peered around him, but the words stopped in her throat. She gulped, blinked, and blinked again, as if she could clear away the nightmarish scene spread before her. The banks of the little stream were pocked with blackened grass, and on it, creatures that oozed whitish substances flopped miserably about. She looked up at the holly tree beside her, wondering why she felt nothing at all from the tree, and realized the tree, and all the others around it, was dead, the berries dull and black amidst the waxy gray leaves. “What did this?” she whispered. “Do you know what happened here?”

To her surprise, Timias nodded, his mouth a straight grim line. “This is what happens when silver falls into Faerie.”

3

White Birch Druid Grove

“Deirdre?” Catrione called. She barged into the courtyard, heedless of the rain sluicing off the edges of the roofs in solid sheets. She glanced frantically around in all directions. How was it possible Deirdre could’ve vanished so fast? She looked back down the corridor but saw nothing. She decided to check each room once more when she heard her title called.

“Cailleach!” She looked up to see Sora scampering across the puddles, skirts kilted high. When she caught sight of Catrione, she paused beneath a dripping overhang and beckoned frantically. “Catrione—a troop of warriors has just come, with a message for you.”

“From the Queen?”

“From your father.”

Now what? she wondered with a sinking heart. She beckoned to Sora. “My father can wait. I need you to help me look for Deirdre.” Tersely, she explained what had happened. “Deirdre ran right past me, but I was behind her—she couldn’t have made it down the corridor in her state. So you take that side and I’ll take this one and we’ll look in every room. She must be hiding in one.”

But a search yielded nothing. Sora twisted her hands in her apron and looked down the corridor to the end, where the door swung open in the wind. “You should go talk to the men, Catrione.”

Catrione bit her lip, calculating the chances of Deirdre climbing out a window in her condition. It was exactly the sort of thing the other girl was capable of doing…before. But now, bloated and swollen and clumsy as Deirdre was, surely such a feat was impossible. Then out of the corner of her eye, Catrione thought she saw a flicker of movement near the door. She bolted down the dormitory corridor, but by the time she stuck her head out, the entire yard appeared deserted. Catrione cocked her head, listening carefully before she answered as softly as she could, “She’s been eavesdropping, apparently. She somehow knew exactly what we’re about.” Not to mention, she scarcely looked human. Catrione suppressed that thought with a shudder and took Sora’s arm. “You go back to Bride and tell her what happened and I’ll go see what this message is from my father.”

Sora nodded and Catrione hurried away. She was halfway there when she realized that in addition to her soaking sandals and bedraggled hem, she’d not stopped to wash her face or comb her hair or change into a fresh coif and clean apron. There was no help for it, she reckoned as she turned the corner into the outer courtyard where she was startled to see, in the light of the brightly burning torches, six or seven horses milling among unfamiliar men who nonetheless were wearing a very familiar plaid. Now what, indeed.

“Lady Cat?”

In the hall, she recognized at once the grizzled warrior who respectfully touched her forearm as she lingered on the threshold, her eyes adjusting to the smoky gloom. “Tully?” Catrione clasped her hand over his and turned her cheek up for a swift kiss. Tulluagh, her father’s weapons-master, was his dearest, most trusted friend. Fengus-Da never let Tully out of his sight for long. As the men crowded around the central hearth, shaking off their wet plaids, holding out their hands to the flames, Catrione glanced around, more confused than ever. There were too many for just a message, she thought. “What’re you doing here? Is something wrong?”

Tully shuffled his feet, frowning down at her with furrowed eyes the color of the watery sky. “Fengus-Da sent me to fetch you home, my lady.”

“Why? What’s wrong?” Catrione stared up at the old warrior.

Tully sighed heavily. He turned his back on the others and glanced over his shoulder. “May I have a word in private with you, Callie Cat?”

“Is it my grandmother? Is she sick?”

Tully put a hand under her elbow and drew her to a shadowy corner, out of the way of the servants scurrying to wait upon the newcomers. “It’s your grandmother, aye, but she’s not sick—well, not in the manner of dying-sick, anyway.”

“How sick, then, Tully?” Catrione stared up at him. “What’s this about?” She spoke softly but with enough of a hint of druid-skill that her words seemed to resonate in the air around him.

The old man’s eyes were steady as he stared back. “Don’t try those druid-tricks on me, Callie Cat. It’s like this. Since the season turned, your grandmother’s been plaguing him. First she started barging into his council meetings, into his practices, his games, even into his hunts. Then she started begging, tearing her clothes, pulling her hair out, moaning and groaning all the day—”

“About what?” Catrione stared up at the old man. Maybe the world really was turning upside down.

“He thinks she’s gone mad, Callie Cat, because all she’ll say is you’re not safe, and then she gibbers and howls and no one can get through to her until the fit passes. We can have you there before MidSummer if we leave by day after tomorrow.”

“Tully, I can’t leave.” Her Sight revealed gray mist, indicating hidden information. Immediately she was wary. “I’m Ard-Cailleach of the Grove this quarter. When I decided not to go home at Beltane, the charge was handed on to me. So till Lughnasa, Tully, I can’t leave, and certainly not now. Things are—unsettled.”

“Unsettled, you say? You don’t know the half.” Tully glanced over his shoulder, then stooped and spoke almost directly into her ear. “I don’t want to scare you. To tell you the truth, I was hoping I’d come and find you gone to Ardagh. Then I could’ve gone home and told him you were out of harm’s way.”

“What are you talking about, Tully? No place is safer than a druid-grove.”

“Callie Cat, do you think I’d be here for just an old woman’s ravings?”

Catrione narrowed her eyes. This sounded more like it. “So now what’s that trouble-making father of mine—”

“Your father’s not the one starting trouble.”

“Then who is?”

“There’ve been sightings of strangers in the high, remote places, and things found—weapons, clothes, equipment—all of foreign make. He thinks it’s the Lacquileans that Meeve’s so fond of, coming over the Marraghmourns a few at a time, hiding out, waiting for some signal, putting out rumors of goblins to keep people afraid.”

“The ArchDruid’s called a convening—”

“Maybe she should consider the possibility that there are no goblins but someone who wants everyone to think so. Your father’s worried about you here. He thinks the deep forests provide too much cover, and these woods could be riddled with them even now. He’s afraid they’ll have no respect for druids, Callie Cat.”

Catrione took a deep breath. “This is all news to me, Tully. We’ve heard rumors of goblins in the southern mountains. In Allovale, now the druids are gone, are the charnel pits emptying? Are the goblins being fed?”

“Aye, as far as I know. The old woman tend such matters now. But, Callie Cat, this isn’t about goblins, it’s about war.”

“I think what you’re really saying is Fengus-Da is going to war, and he wants me out of it. Isn’t that it?”

“No. He means to confront Meeve at MidSummer and raise the issue with the chiefs, but he’s not intending to go to war. He says you and all the sisters, all the brothers here are welcome at Eaven Avellach.”

Catrione blinked, her mind racing rapidly. From no druids, to an entire groveful—not as many as Meeve could muster out of Eaven Morna, of course, but impressive enough if they all crowded into the audience hall at Eaven Avellach. Outward show was everything. So was Tully’s visit motivated by real concern, or simply her father’s attempt to co-opt the White Birch Grove’s support, whether they meant to give it or not? “Maybe he’s right, Tully.” This wasn’t something she could decide in a blink. “But in the meanwhile, I can’t go anywhere, because among everything else that’s happened today, one of our sisters is—”

“Is definitely missing.”

Catrione jumped. Tall, stern, as composed as Catrione felt frazzled, Niona stood at her elbow, as unsmiling and unwelcome as Marrighugh, the bloodthirsty battle-goddess of war, who was already, apparently, awake and marching across the land. Niona had come in with the servers who were now passing trays of oat cakes and tall flagons of light mead, and despite all the frustrations of the day, she somehow managed to look as cool and calm as a cailleach was supposed to look, her apron spotlessly white, her coif perfectly arranged over her smooth hair. Beside her, Catrione felt like a small girl caught masquerading in her mother’s robes. “A word with you, if you will, Cailleach?” Niona nodded a quick smile to Tully, but the expression in her eyes was grim.

“Please, Sir Tully, eat and drink,” Catrione said. “We’ll speak more when you’re refreshed.” With a tug of his forelock, Tully seized the nearest flagon, and as he tilted his head back, she followed Niona a few lengths away, her wet soles squeaking audibly. “Have they found her?”

Niona shook her head. “Not yet. I’ve taken the liberty of calling up the brothers and we’re starting a systematic search—it’s everyone’s guess she’s hiding somewhere inside these walls. We’ll find her—sooner or later she’ll get hungry.”

“Catrione, dear?” Baeve approached and met Catrione’s eyes with uncharacteristic softness.

“What is it, Baeve?” asked Niona.

“Yes?” Catrione replied, controlling her urge to elbow Niona aside.

But Baeve ignored Niona entirely. “My dear.” She looked directly at Catrione. “About Bog.”

“Bog.” She’d nearly forgotten him. She bit her lip to keep the sob that rose in her throat from escaping as she remembered his limp body lying on the hearth rug.

“You told Sora that Deirdre was waiting for you?” When Catrione nodded, Baeve continued, “She’d time, then—”

“Time to do what,” interrupted Niona.

But again Baeve ignored her and spoke softly, gently, to Catrione. “It seems his neck was broken, child. Someone killed him.”

Niona made a horrified sound, and Catrione covered her face with both hands. “Are you saying Deirdre killed him?” Niona asked.

Catrione’s mind reeled. “We…we don’t know for sure Deirdre killed Bog,” she heard herself say weakly.

At that Niona rounded on her. “Come now, Catrione. We all know you love Deirdre, but you have to face facts. Who else was in your room? Who else would have reason to do such a thing?”

The possibility that Deirdre, once her best friend and confidante, was capable of killing an animal that would never have harmed her sickened Catrione. But Deirdre never showed any compunction about killing anything if it needed to be done. She was as capable of squashing a moth in the woolens as she was wringing a hen’s neck for dinner. Catrione saw Deirdre’s strong hands wrapped around a squawking chicken’s throat and deliberately squelched the memory. Even if she were capable, that doesn’t mean she did it.

“I don’t think it was Deirdre who killed Bog,” Baeve said softly.

“Then who do you think it was?” Niona cocked her head.

“I think that thing inside her has some kind of hold,” Baeve answered.

Niona’s brows shot up. “You mean you think it’s the child?” She made a little noise of derision, but Baeve wouldn’t be cowed.

“I’ve been catching babies here for over forty years, Sister Niona, and this is the most unnatural thing I’ve ever seen in all my time. I’ve had babies go past their dates—oh, long past, a month or more. But they die, they don’t survive. And their mothers are sickened, but they don’t start to look anything like that thing that Deirdre’s become.” She looked at Catrione. “I asked Sora to check the Mem’brances—”

“Those old barks are half crumbled to pieces—” began Niona.

Catrione cut her off. “Sister, make sure there’s someone in the kitchen at all times. There are lots of places to hide.”

Niona shut her mouth with an audible snap and marched away, back straight, shoulders rigid.

“Have patience,” murmured Baeve, then jerked a thumb over her shoulder at the men. “What’s this about?”