Полная версия

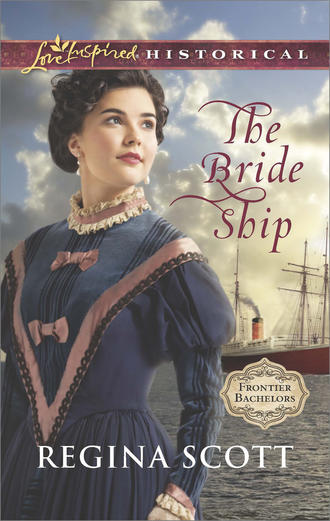

The Bride Ship

But at Gillian’s statement, he pushed back his hat. “Clever of you, little miss, to notice,” he said with a bow. “I’m your father’s brother. And I’m here to bring you home.”

Gillian’s eyes widened. Allie sucked in a breath and stepped between them. How dare he try to use her daughter against her!

“Gillian’s home is with me, sir,” she informed him. “And I am heading for Seattle.” She gave Gillian a hug before patting her back and pushing her toward Catherine. Catherine took the little girl’s hand and turned to give her own name to the purser.

“I’m not trying to usurp your place,” Clay said quietly as he straightened and the other women returned to their places in line. “I thought Frank’s daughter deserved to know her family.”

Guilt whispered; she could not afford to listen. She knew that by taking Gillian to Seattle, she was cutting off everyone the little girl had ever known. But Clay had been away for so long. He couldn’t understand how his family had tried to control Allie, to control Gillian. He knew she’d refused to leave Boston once. How could he realize how important this trip was to her now?

“You are wasting your five minutes, sir,” she said. “I believe you only have three left.”

His mouth compressed in a tight line. He glanced about, then led her through the crowds and a little apart from the gangway to the shelter of a stack of crates awaiting loading. Allie could see Catherine taking Gillian aboard the ship. Some of the tension seemed to be going with them. Whatever happened now, at least her daughter was safe.

She turned to find Clay eyeing her. “Why are you here, Allegra?” he asked.

Though his tone was more perplexed than demanding, she felt her spine stiffening. “I would think that obvious. We’re going with Mr. Mercer to Seattle.”

“And you think that’s your best choice for a future?” he asked with a frown. “What about Boston? Your place in society?”

Her place in society? Well, she’d once considered it precious, and he had cause to remember. She was the one who didn’t like remembering. She’d been so sure then of what she’d wanted. She’d been taught to manipulate to achieve her goals, yet she hadn’t realized how easily she’d been manipulated until it was almost too late.

She puffed out a sigh of vexation that hung in the chill air between them. “You honestly think I should be content to stay in Boston? And this from the man who ran away to join the Wild West show!”

A smile hitched up, and it somehow seemed as if the gray day brightened. “I wanted to see the Wild West, not play cowboy in a show,” he replied. “And from what I’ve seen, the Northwest territories are no place for a woman.”

“Which is precisely why women are needed,” Allie argued. “You can’t tell me Seattle won’t be improved by teachers, nurses, seamstresses and choir leaders.”

He chuckled. “That statement merely shows what little you know of Seattle. There are few children to teach, a single struggling hospital for the nurses, no call for fancy clothes for the seamstresses.”

Allie’s eyes narrowed. His description hardly matched the information Mr. Mercer had given them. How could Clay know so much about Seattle? If her in-laws had ever received letters from him, they hadn’t shared the news with her. And Frank, of course, rarely spoke of Clay. He thought the entire matter too painful for her.

“So you’ve seen Seattle,” she said, watching him.

His gaze met hers. Up close, the changes of time were obvious: the fine lines beside his eyes, the tension in his broad shoulders, the way his smile turned from pleased to grim.

“I’ve been there,” he said so carefully she could only wonder if he’d robbed the bank. But perhaps they didn’t have a bank, either!

“Then you must know why we’re needed,” Allie told him.

“Besides being someone’s wife?” he asked, rubbing a hand along his square jaw. “No. Seattle is a scattering of houses in a clearing, five hundred people, give or take. And the outlying settlements are worse. I heard most of these ladies going with Mercer are orphans. They’ve nowhere else to turn. You have a family, a home, opportunity for a future. I can’t see you as one of Mercer’s belles.”

At least he hadn’t used one of the unkind names she’d seen in the newspapers. Cargo of Heifers. Petticoat Brigade. Sewing Machines. The editor of one of the local papers had expressed extreme doubt that any girl going to seek a husband was worthy to be a decent man’s wife. What, did the rest of the country expect every woman who’d lost a sweetheart, a husband in that horrible war to simply stop living? That they couldn’t find employment instead of decorating a man’s home?

Anger bubbled up inside her. “I have no intention of seeking a husband in Seattle. And may I remind you that you had a home and opportunities once, too. That didn’t stop you from leaving.”

His jaw tightened. “I knew what I wanted and what I was leaving behind. I doubt you do.”

Didn’t she? How many nights had she lain in her canopied bed, warm, safe, suffocating? How many times had she prayed for wisdom, for guidance? Her prayers had been answered with a dream, a future for her and Gillian that didn’t include marrying someone the Howards picked out. When Allie had seen the advertisement in the paper for teachers and other workers in far-off Washington Territory, she’d known it was the pointing of God’s finger. She’d been the one to close the door on adventure once. Now He’d opened it, and she intended to follow His lead.

“Save your doubts, Mr. Howard,” she said. “Save your breath, as well. You gave up the right to order me about years ago.”

Clay’s brows went up, and he took a step back to stare at her. Allegra Evangeline Banks Howard would never have spoken to a gentleman that way, particularly not her husband’s brother.

“You’ve changed,” he said.

“How perceptive of you to notice,” she replied. “Did you think I had no more to worry about than which dress to wear? Motherhood, and widowhood, mature a woman in a dozen ways. And this trip will do more.”

He sighed and dropped his gaze to the wooden pier, where his boots scuffed at an iron nail. “I can see you’re certain, but I can’t let you get on that ship, Allegra. You have no idea how to survive in the wilderness.”

She knew he was right. Who was she to take on such a challenge, to brave the unknown? But her will rose up even as her head came up.

“Clayton Howard,” she said, breath as sharp as her words, “if you can learn, so can I. Now, you have had your five minutes, sir. Nothing you’ve said has dissuaded me from leaving. Thank you for coming. Good day.”

Before she could push past him, he held up his hands as if in surrender. His words, however, were far from capitulating. “I can’t demand that you come with me, Allegra, though I’ve no doubt my mother expected me to do so. She’s ready to welcome you back to the family. Isn’t that better than heading off to the wilderness alone?”

So he was willing to admit that he was here on his mother’s behest. She couldn’t help the frustration building inside her. Was she never to be free?

“I think it’s time Gillian and I made our own family,” she informed him. “And you can tell that to your exalted mother. And as for the other member of your family, your cousin Gerald, you can tell him that I wouldn’t marry him if he was the last man on earth, and sending bullies after me isn’t going to persuade me otherwise!”

He cocked his head. “Gerald has been pressuring you?”

That’s what he heard? Not that she was her own person, capable of making her own decisions. Not that she considered him nothing but a bully to chase after them this way. No, he had to fixate on the rival, the cousin who seemed intent on inheriting the considerable estate that would have been Clay’s if his father hadn’t disowned him when Clay headed west.

“Every day,” Allie told him. “In every possible way. He’s become extremely tiresome.” It was the most polite way to put it. At times, Gerald had looked at her with a glint in his eyes that made her feel as if she had suddenly fallen through the ice on the pond below the house. It was as if he coveted her, as if she were a possession. And Clay’s mother had encouraged him. She shuddered just remembering.

Clay must have seen her movement, for he took her arm. “Allow me to escort you back to the hotel,” he said. “We can talk further where it’s warmer.”

Behind her, the Continental blew its horn, the blast piercing the cold air. She would not let the ship leave without her. Her bags were already aboard. And she would never abandon Gillian.

She pulled her arm from Clay’s. “Your hearing must have been affected by your travels, sir. I am boarding this ship. If you insist on conversing further, you’ll have to board it with me.” She turned for the ship, keeping her head high, her steps measured. She wouldn’t look back, not to Boston, and not to Clay.

For all she had once wished otherwise.

* * *

Clay stared at Allegra as she headed for the gangway. She walked gracefully, as if on her way to a ball. She had no idea she was heading into trouble instead.

What am I to do with her, Lord?

The prayer held more exasperation than appeal. He’d ridden, by hired horse and stagecoach, from the Northwest territories to Boston in the last month, hoping to reunite with family after news of Frank’s death a year ago had reached him, courtesy of an old family friend. Though Frank was beyond Clay’s help, he had considered it his duty to ensure his brother’s widow was well provided for. But he’d met failure on all sides. The one task where he’d thought he could still succeed was to convince Allegra to return to Boston where she would be safe. Now even that seemed to be denied him.

But he’d never been one to give up without a fight.

His purpose, as he saw it, was to protect Frank’s wife and child. He’d never be a family man like Frank, steady, reliable, but he could at least make sure Allegra and Gillian had a solid future. If they refused to return to Boston where they belonged, then he had only one way to accomplish his goal. He had to return west in any event.

I know it may be crazy, Lord, but surely this is what You’d want me to do.

He shoved his hat down on his head a little farther and waited in the shadow of the crates as the last of the women filed up the gangway. The purser glanced through his notes with a frown, as if he thought he must be missing someone. Then he shrugged and climbed aboard, as well. As soon as the way was clear, Clay strolled up the gangway and onto the ship.

No one stopped him, ordered him to produce his ticket. With his satchel in his hand, he probably looked like a typical passenger, even if he wasn’t one of Mercer’s maidens. As it was, the crew and officers were far too busy preparing to sail to pay him any mind.

And the crowds were even denser on the deck than they had been on the pier. He was surprised to see several families aboard, older husbands with wives and children in tow, brothers escorting what were clearly sisters by the similarity of their features. People milled about, looks ranging from excitement to terror. At least some of them knew what they were leaving behind. Going from one coast to the other happened once in a lifetime for most people.

Clay moved among them, keeping an eye out for Allie and Gillian. Even with all the passengers on deck, it shouldn’t have been that hard to find them. As far as he could see, the entire ship was about as long as the Howard mansion in Boston but only half as wide.

The main deck circled the ship, with an upper deck above one of the blocky buildings. Though the black funnel sticking up in the center of the deck sputtered a cloud from the steam engine, two masts rose higher into the air. It seemed the Continental could sail under wind power, as well. The three buildings along the deck would house the wheel, the captain’s quarters and the officers’ mess, and the first-class accommodations, Clay guessed. The stairs running down beside them would likely take the passengers belowdecks, where they’d find another salon and staterooms for the ordinary passengers.

And there, just about where the first mast towered over the deck, Allegra stood with some of the other women, faces set resolutely toward the mouth of the North River.

Just then, the horn bellowed, and little Gillian cried out, arms reaching for her mother. Allegra gathered her close, bent her head as if to murmur reassurances. Something hot pressed against Clay’s eyes.

That little girl has lost so much, Father. I didn’t have a say in the matter, but now that I know about her, I can’t see her hurt further.

Neither could Allegra. That much was obvious. She raised the little girl’s chin with one finger, smiled at her, lips moving as if she promised a bright future.

How could he take that future from them?

He pushed his way through the crowds to their sides. Allegra looked up, then straightened at the sight of him, eyes widening.

“What are you doing?” she cried. “We’re about to sail!”

As if to prove her point, two of the crew began to haul in the gangway.

Clay glanced over his shoulder at the gangway, then back at Allegra. “It seems you’re set on going, Mrs. Howard. And that means I’m going with you.”

* * *

“What are you talking about?” Allie cried. He couldn’t be coming with them. Surely he wasn’t part of Mercer’s expedition. She’d never heard his name mentioned, hadn’t seen him at the hotel with the others. If she had, she might not be here now.

But before he could answer, the ship groaned, heaving away from the pier. Everyone around her rushed to the railing, carrying her and Gillian along with them, and for a moment, she lost sight of Clay.

The sight below them was compelling enough. From the pier, dozens of people waved and cheered. Boys threw their hats in the air. Women fluttered handkerchiefs. After the reception Mercer’s belles had received in the New England papers, Allie found it hard to believe so many New Yorkers would stand in the cold to watch them set sail. It was as if she and her friends were making history.

Those on the Continental were even more excited. Maddie was blowing kisses to the crowd below. Other passengers raised clasped hands over their heads in a show of victory. Even Catherine unbent sufficiently to give a regal wave. No one seemed bereft at what they were leaving behind. Hope pushed the ship down the bay. Hope brightened every countenance. Even the air tasted sweeter.

Perhaps that was why it was so very painful when hope was snatched away.

“Attention! Attention, please!” Mr. Debro hopped up on one of the wooden chests that dotted the deck and waved his hands as if to ensure everyone saw him. “We’ll be stopping shortly at quarantine near Staten Island. Everyone to the lower salon on the orders of Captain Windsor. This way!”

Allie and Maddie exchanged glances, and she saw worry darken her friend’s gaze.

“Very likely it’s nothing to concern us,” Catherine said as if she’d seen the look, as well. “The captain probably wishes to address the passengers before we reach the ocean.”

“Of course,” Allie agreed, but the frown on Maddie’s face said she wasn’t so sure. Allie took Gillian’s hand, and Catherine and Maddie fell in beside them as they headed for the salon.

It was a simple room, with a long wooden table scarred from frequent use. Around it, smaller tables and chairs made of sturdy wood hugged the white-paneled walls under the glow of brass lanterns. At one end, doors opposite each other led up to the deck, with another opening amidships that must lead to the upper salon. Other doors recessed along the way appeared to open onto staterooms. Across the back, a wide window and narrow door gave access to the galley where copper pans glinted in the glow from the fire in the massive black iron stove.

Already the room was crowded, but there seemed to be fewer women than Allie had expected. She’d heard that the expedition was to include as many as seven hundred female emigrants, yet she estimated at most sixty flitting from one group to another. And still she caught not a glimpse of Asa Mercer.

Catherine excused herself a moment to go speak to Mr. Debro, who was frantically shuffling his papers.

Gillian tugged on Allie’s skirts. “Where’s our new room, Mother?”

Mother. The formal word always reminded Allie of how she’d nearly failed her daughter. Gillian’s first word had been Mama, her second Papa. Allie had spent most of her time with her baby daughter, marveling over each change as Gillian grew into a toddler. But as soon as she was walking well, her grandmother had insisted on a governess.

“A small child can be so challenging,” she’d told Allie and Frank over tea in the formal parlor of the Howard mansion. “You’ve never been a mother before, Allegra. You have no experience with children. For Gillian’s sake, we should look for someone older to help you. Don’t you agree, Frank?”

Of course, Frank had agreed. Frank never argued with his mother. Allie had already been wondering about her ability to raise such an active little girl, so she’d agreed, as well. Gillian had moved into the nursery suite with a governess, and her next words had been please and thank-you and little else in between. Mama had never returned to her petal-pink lips.

“We’ll know where to go soon,” Allie promised now, taking her daughter’s hand and giving it a squeeze. “And we can sail off to adventure.”

Gillian nodded, but her frown told Allie she wasn’t sure adventure was something to eagerly anticipate.

Catherine returned then, her rosy lips tightened in obvious disapproval.

“This is a shameful state of affairs,” she said to Maddie and Allie, where they were waiting with Gillian along one wall. “What sort of ship allows stowaways to sneak aboard?”

Stowaways? Allie immediately glanced around for Clay and spotted him leaning against the far wall, a head taller than any other man in the room. He’d been clear from the start that he wanted them to leave. Surely he’d never paid his passage. Had he caused this commotion?

Just then, the young purser raised his voice from where he stood by the doorway to the upper salon.

“May I have your attention, ladies and gentlemen?” he called, and the other voices quieted as people shifted to see him better. Allie was close enough to notice the sheen of perspiration on his brow under the brown cap.

“There seems to be some misunderstanding as to which people have paid their passage,” he said, confirming Catherine’s statement. “When I call your name, please accompany me to the upper salon, where Captain Windsor and the authorities are waiting to examine your tickets. If you do not have the appropriate ticket, you will be asked to gather your things and embark on the tug alongside us, back to New York.”

Allie felt as if the air had left the room. She pulled Gillian closer as voices rose in protest.

“See here, sir,” an older gentleman declared, pushing his way to the front. “I’ve paid for a wife and five children. I’ve spent all we had waiting for this infernal ship to sail. If you send us back, where do you suggest we go?”

“Mr. Mercer assured me no money was needed,” another woman called. “He cannot go back on his word!”

“Where’s Mr. Mercer?”

“Yes, find Mr. Mercer!”

The cry was taken up by a dozen voices.

The purser raised his hand and managed to make himself heard above the din. “Mr. Mercer is presently unavailable, but rest assured, he has been consulted on the matter.”

Allie’s stomach knotted. She had only a letter from Asa Mercer, assuring her and Gillian of places on the ship. She’d never received an actual ticket. Would the captain count her letter as sufficient evidence to allow them to stay? Was her adventure over before it had begun?

Chapter Three

As soon as Clay heard the reason they had stopped, he knew he had to act. While the room erupted in protest, he slipped out the side door and circled around for the upper salon.

It was a more opulent room, with leather-upholstered armchairs positioned along the paneled walls for conversation and a large table running down the center for meals. Doors with brass latches and louvered windows opened onto spacious staterooms. The scent of fresh paint hung in the air.

Another table had been positioned across the top of the salon, where three men, one seated, two flanking him, waited in the brown-and-gold uniforms of the Holladay line.

Clay strode up to them and nodded to the man at the table. “Captain Windsor, sir. I’m Clayton Howard, and I’d like to report a stowaway.”

The captain eyed him. He seemed the very embodiment of the seas he sailed—gray hair, gray eyes, strong body and unyielding disposition.

“Indeed, Mr. Howard,” he intoned. “We are here to make that determination.”

“I’ll spare you the trouble,” Clay said. “I haven’t paid my passage, and I’d like to rectify that matter. Will you take gold certificates?”

Captain Windsor tilted up the cap of his office. “Certainly. But I must ask why you didn’t purchase a ticket beforehand.”

Clay couldn’t lie. “I came here intending to stop my brother’s widow from sailing. Since she is determined to make the trip, I’m coming with her.”

The officers behind the captain exchanged glances, but whether they thought him a tyrant or a fool, he couldn’t tell.

“Very well, Mr. Howard,” the captain said. “Some of the passengers who were supposed to have boarded did not make the sailing, so we should have room for you. Give your money to Mr. Debro when he arrives with our first passenger, and welcome aboard.”

Clay inclined his head. “Would you allow me to stay in the room until I’m certain my sister-in-law’s documents are sufficient?”

Captain Windsor agreed, and Clay went to sit on one of the chairs along the wall, where he could monitor the proceedings.

He thought it would be a simple matter. After all, how many stowaways could have slipped by Mr. Debro’s watchful eye? However, what he saw over the next hour disgusted him.

He knew the story of how Asa Mercer had come by the use of the S.S. Continental, which had seen service as a troop carrier in the war. The so-called emigration agent had written home to Seattle to boast of his accomplishment. None other than former general Ulysses S. Grant had allowed Ben Holladay to purchase the ship at a bargain and refit her for duty as a passenger ship so long as he agreed to carry the Mercer party to Seattle on her first run.

Mercer and Holladay had apparently settled on a price for passage, and Mercer had provided the list that Mr. Debro had used to allow passengers to board. But it was soon apparent that Mr. Debro’s list did not match Captain Windsor’s instructions from Mr. Holladay. Someone had cheated these people, but Clay couldn’t be sure whether it was Asa Mercer or the steamship company.

Everyone claimed to have paid or been told payment was unnecessary, the fare was courtesy of the fine people of Seattle. Mercer must have confessed how he’d accepted money from a number of gentlemen to bring them wives. Clay could only hope Allegra wasn’t one of the women with a husband waiting. The fellow was doomed to disappointment, for Clay still had hopes of discouraging her from settling in the wilderness. Surely over the course of their trip he could find the words to persuade her.

But the other passengers were more discouraged. Two men and their families, disappointment chiseled on every feature, had already been escorted downstairs to identify their belongings, along with a few crying women. One, Mr. Debro reported, had barricaded herself in a stateroom, refusing to leave. Others threatened retribution.

Allegra was different. She must have left Gillian below with friends, for when it was her turn, she glided into the room alone, head high, smile pleasant. Her gaze swept the space, resting briefly on Clay. Her look pressed a weight against his chest. She passed him without comment and went straight to the captain, pulling a piece of paper from the pocket of her cloak and holding it out as if allowing him to kiss her hand.