Полная версия

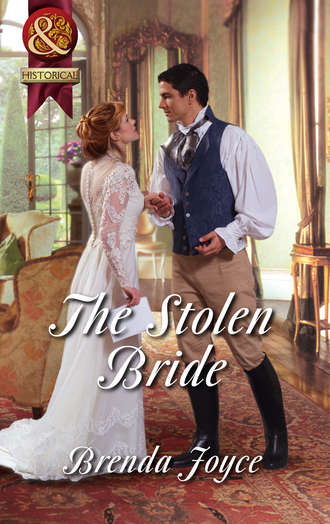

The Stolen Bride

Suddenly real panic began. She had been a failure in London. She had hated every ball, where she had been snubbed because she was Irish and tall and because she preferred horses to parties. The English had been terribly condescending. She was going to be a failure in Chatton, too—she was certain of it. Even if Peter had never questioned her background, once he got to know her he would be condescending, too.

Because she wasn’t proper enough to be his English wife. Proper ladies would not dream of riding astride in breeches, let alone doing so alone. And while a few were brave enough to foxhunt, ladies did not shoot carbines and fence with masters; ladies loved shopping and gossip, which she abhorred. Peter didn’t really know her—he didn’t know her at all.

Ladies don’t lie.

It was as if Sean stood there beside her, his silver eyes oddly accusing. If only he hadn’t left her. How could it still hurt, on the eve of her wedding, when she had invested the entire past year of her life in her relationship with Peter?

And Eleanor knew she was on that runaway horse yet again. Her wedding was in three days and until recently, she had been pleased. In fact, she had been very caught up in the wedding preparations and she had been as excited as her mother. It would be the scandal of the decade should she now call it off. She was having bridal jitters, nothing more. Peter was perfect for her.

Very purposefully, Eleanor halted and closed her eyes, trying to find an image that would chase away, once and for all, every fear and doubt she had. She saw herself in her wedding dress, the bodice covered with lace and pearls, the huge satin skirts boasting pearl and lace insets, the train an endless pool of satin trimmed in beaded lace. Peter was standing beside her, blond and handsome in his formal attire. They were exchanging vows and Peter was raising her veil so he might kiss her.

The veil was removed from her eyes. Peter was gone. Standing before her was a tall, dark man with shockingly silver eyes.

Ladies don’t lie, Elle.

Eleanor could not bear the renewed surge of grief. She did not need this now. She did not want this now.

“Go away!” She almost wept. “Leave me alone, please!”

But the damage was done, she thought miserably. She had dared to let him back into her mind, and now, just days before her wedding, he wasn’t going to go away. She had known Sean O’Neill since she was a child. His mother had been widowed by the British in a terrible massacre, and her own father, a widower at that time, had married Mary O’Neill, taking Sean and his brother in. Although he had never legally adopted the O’Neill boys, he had raised them with his own three sons and Eleanor, treating both boys as if they were his own.

There were so many memories now. Even as a tot, she recalled thinking Sean a prince, never mind that his family had been impoverished Irish Catholic gentry. Toddling after him, screaming his name, she had tried to follow him everywhere. At first he had been kind, allowing her to piggyback on his strong but scrawny shoulders or leading her back by the hand to her nurse. But his kindness had become irritation as Eleanor grew into a small child. She would hide in the classroom to watch him at his lessons and then advise him on how to do better. Sean would summon the tutor, ordering her put out, telling her to mind her own affairs. Unfortunately, even at six, Eleanor’s math was better than his own numbers. If he thought to escape the day’s lessons, she knew, and she would follow him out to the pond, also intent on fishing. Sean had tried to scare her with worms but Eleanor had helped him bait his hooks instead. She was better at that, too.

“Fine, Weed, you can stay,” he had grumbled, giving up.

He would ride across the Adare lands with his brothers, an almost daily event. Eleanor had a fat, old Welsh pony, and she would follow, refusing to be sent home. More times than not, with vast annoyance, Sean had caved in to her, allowing her to send the pony home and letting her ride double behind him.

Her favorite ploys, though, had been to spy or steal. Sometimes she hid in a closet to eavesdrop on Sean, overhearing the most fascinating young male conversations—most of which she had not understood. At other times she would take a beloved possession—his favorite book, his penknife, a shoe—just to make certain he hadn’t forgotten her. When he realized, he would chase her furiously through the house or across the grounds, demanding the item back. Eleanor had laughed at him, loving the chase and knowing he could not catch her unless she allowed it, as she was too fast for him.

An ancient ache was assailing her, yet she realized she had been smiling, too. She found herself standing some distance from the stables, her stallion now contentedly grazing, and tears pricked at her eyes. Sean was gone. In her heart she might yearn for his return, and she might still miss him terribly, but what good was that? Irrefutable logic demanded that if he could come back—or if he wanted to—he would have returned by now. Common sense also proved a very painful fact: he had never once in their entire lifetime indicated that he felt anything but brotherly affection for her.

Eleanor realized that a man was approaching, having come out of one of the many entrances of the house. Instantly she recognized her oldest brother, Tyrell. He was so terribly preoccupied with affairs of state, the earldom and the family that they did not spend much time together, but there was no one more dependable or more kind. One day, he would be the family patriarch, and every problem and crisis, both personal and otherwise, would be brought to him for resolution. She admired him tremendously; he was her favorite brother.

Tyrell paused before her and she was very pleased to see him. Tall, muscular and dark, he smiled at her. “I am relieved that you are all right. I saw you from a window and when you dismounted, I feared something was amiss.”

Somehow Eleanor forced a smile. It felt sad and fragile. “I am fine. I decided to let Apollo graze, that’s all.”

Tyrell’s dark blue gaze was searching. “You were never one to dally in bed, but I thought we had an understanding that you would not ride about this way while we have so many guests.”

Eleanor tried to keep smiling, but she avoided his eyes now. “I had to take a gallop this morning.”

He was blunt. “What is wrong?”

She stiffened, Sean’s image filling her mind. Oddly, she thought she could feel him with her now, somehow. Shaken, she glanced around, but only a gardener and his boy were passing on the lawns behind her.

Tyrell caught her free hand. “Most brides would love some extra beauty sleep, sweetheart,” he said kindly.

“Extra sleep will hardly make me shorter,” she managed tartly. “True beauties are not as tall as most men—and taller than their own husbands.”

His smile was brief. “Have you decided that you wish a taller husband? It is a bit late to change grooms.”

Damn it, her first thought was that her head barely reached Sean’s chin—even in her boots. Dismayed Eleanor bit her lip. “I am very fond of Peter,” she somehow said. “I don’t care that we stand eye to eye when I am in my bare feet.”

“I am glad, because he is very smitten with you,” Tyrell said seriously. “Last night during the dancing, he could not take his eyes from you. He also partnered you three times. A fourth time would have been scandalous.” He laughed.

Eleanor did not. “That is because I am a ghastly dancer, missing every other step.” She met his gaze. “Do you really think he is smitten? I am bringing a fortune to the marriage.”

“It is rather obvious that he is besotted, Eleanor. Why are you crying?”

Eleanor tensed. She was ready to tell Tyrell everything, she realized. She so needed a confidante. “Tyrell, I am confused,” she heard herself whisper.

He gestured at a stone bench, his expression kind. Eleanor handed him the stud’s reins and walked over, sitting down, that odd desperation coming over her. “I do care about Peter. He is so witty and so considerate, and I have enjoyed the time we have spent together. You know I detest balls, but these past few months, with Peter attending me, I really haven’t minded.”

“He has been good for you, Eleanor,” Tyrell said seriously. “The entire family is agreed on that. He is turning you into a rather proper and conventional lady.”

“I have truly tried to be ladylike,” she said.

Ladies don’t lie, they don’t steal and they don’t spy, Elle.

Panic overcame her and she stood. “Tyrell! Sean is haunting me now. I can’t do this! I really can’t! We should call off the wedding— I don’t care if I remain an old maid on the shelf!”

His eyes were wide. “Eleanor, what has brought this on?” He spoke with a wary tone.

“I don’t know!” she cried. “If only we knew where Sean was—if only we knew what had happened to him.”

Tyrell was silent.

She filled that silence. “I am aware that you think he’s dead. I know what the Runners said. I still miss him,” she whispered, and to her shock, she realized she missed him so much that it was like a knife stabbing through her heart.

Tyrell put his arm around her. “You have loved him your entire life and he has been gone for four years. I am certain a part of you will always miss him. Peter is a great match for you, Eleanor, in every possible way, and I cannot tell you how pleased I am that he is genuinely in love with you, too.”

She barely heard. “But how can I really go through with this when I am feeling this way? I am so unsettled! I almost feel as if Sean is here to stop me from going forward! I am going to be Peter Sinclair’s wife. I am going to bear his children. I am going to live in Chatton.” And she gazed pleadingly at her brother.

“Even if Sean were here, which he is not, would it really make a difference?”

“Of course it would!” Then she flushed. “I comprehend your point. He never cared for me the way that Peter does. I know that, Ty. Why do I have to be thinking of him now, of all times?”

“All brides become exceedingly nervous before their weddings, or so I have been told.” Ty smiled reassuringly at her. “Maybe you are looking for excuses to delay the event, or to even walk away?”

She studied him. “Maybe you’re right. What should I do?”

Tyrell touched her. “Eleanor. You waited for almost four years for him. What do you think to do? Wait four more years for his return?”

Her heart wished to do just that. She finally said, “He’s not dead, Ty. I know it. I feel it. He is very much alive. He has hurt me terribly, but one day, he will come back and tell us what happened and why.”

“I hope you are right,” Tyrell said grimly. He put his arm around her again. “A very wise person once said that we do not choose love. It chooses us. True love never dies, Eleanor.”

“What am I to do?” she begged.

It was a thoughtful moment before Tyrell spoke. “Frankly, I am not surprised that now, on the eve of your wedding, you would be tormented by thoughts of him. Given the past, it would be odd if you did not think of him now. But that doesn’t necessarily mean that you should forsake your marriage to Sinclair.”

Eleanor started. “What do you wish to say?”

Tyrell hesitated.

Eleanor seized his sleeve. “Ty, you may be frank.”

His jaw was tight. “I wish for you to have a life of your own. A home and family of your own, a future with the joy of children. Sean has never returned your feelings, and we do not know where he is or if he will ever return. Sinclair is offering you a genuine future. I think it would be mistake for you to jilt him now. You will not find this opportunity again. Not because of your age, a hindrance enough, but because Sinclair is such a good match for you.”

Eleanor realized she did not care for his meaning. She slumped onto the stone bench, consumed with despair and doubt.

Tyrell spoke again, with great care. “Sinclair is an honorable man. He is, by birth, nature, breeding and character, a true gentleman. I do think, should you go through with the wedding, he might have some trouble ruling his roost. But I don’t think he will care! He has fallen in love with you, Eleanor, and I very much approve of that. Are you genuinely considering breaking the contract on the off chance that Sean will soon return and, even more improbably, realize that he loves you?”

She was so overwhelmed she could barely think. Tyrell was right. She was being absurd. And she had given her word to Peter Sinclair.

“Of course, if you do not care for Sinclair at all, I would not want you to marry him,” Tyrell said softly. “But from what I have seen, you seem genuinely fond of him. I have been pleased to see you laughing again, Eleanor. And I never thought to see you smile during a quadrille.”

Eleanor inhaled and made her decision. “I am so fortunate.” She did not feel fortunate at all. “What woman is allowed to make such an important choice? What choice is there to make? Peter is titled, wealthy and handsome, he is kind, and he loves me. I must be the biggest fool in the land to be thinking, even for a moment, of breaking my marriage for a man who doesn’t want me—a man who isn’t even here, a man the whole world thinks is dead.”

“You have never been foolish,” Tyrell said with a smile. “But I am relieved that you will go through with the wedding. I can barely begin to describe the pleasure a family of your own will bring you.”

She just looked at him, reminding herself once again how fortunate she was while trying to push Sean’s dark image out of her mind. She must never entertain it, or her doubts, again. “You scandalized all of society by choosing Lizzie over your duty, Ty. You married for love—for true love—so I am not sure I am going to enjoy all that you have.”

“You won’t know, not if you don’t try,” he said. “I would never encourage this union if I did not have great hopes for it. I want you to be loved and I want you to be happy, Eleanor. We all do.”

She threw her arms around him. “You are my favorite brother! Have I ever told you that?”

He laughed. “I believe you have,” he said with an affectionate smile. “And, Eleanor? Please, do not become too proper!”

She finally smiled. “As it is an entire ruse, you need not fear a shocking transformation of character! Is not my current attire proof?” She gestured at her breeches.

He did not look down. “On that subject, I must object. Eleanor, please promise me you will return to your riding habit if you must gallop at dawn? At least until after the wedding—and the honeymoon. I would then advise you to humbly ask Peter for his permission to ride astride. I have no doubt you can convince him of anything you truly desire.”

She sighed. “I will try to be humble, Ty. And you are right. I do not need a scandal of my own making now. I will steal into the house so no one sees me. Are the gentlemen up and about?”

“A large group is intent on fishing today, so yes, they are in the breakfast room. I suggest you go in through the ballroom. The ladies remain asleep, of course, except for my wife.” His soft smile was instantaneous.

She quickly envisioned her escape into the house, and her planning calmed her. “Thank you, Ty. Thank you for your pearls of wisdom.” She stood. “You have soothed me. I have come to my right mind. I feel much better.”

Tyrell kissed her cheek. “I happen to believe you are making the right decision. I think, in time, your love for Peter will grow. I think there is every chance that, once you bear his children, there will be no regrets. You deserve all life has to offer. Sinclair can give you that.”

“Yes, you are right. You are always right, in fact.” She grinned at him. It never hurt to flatter the heir to the estate.

He laughed. “My wife would disagree. You need not be obsequious, my dear.”

“But you are the wisest of all my brothers! Can you take Apollo back to the stables for me?” she asked in the same breath.

“Of course.”

Eleanor hugged him and strode toward the house, looping past the west wing so she could take the terrace to the ballroom.

Tyrell remained still, watching her. His smile faded. He had been terribly fortunate in his own life to avoid a prearranged match and to marry for true love. Eleanor remained as deeply in love with Sean O’Neill as she had ever been—it had never been more obvious. These past few months she had been acting a charade. He could not help himself now, for his wife had made him a romantic. He wished that circumstances were different—he wished she were marrying where her heart lay. But it was not to be, and Sinclair was offering her a future. Even if Sean did return, he could offer her nothing now.

He tensed. He had just kept the truth from his sister and he dearly hoped that in doing so, he had done what was right.

For last night, well past the conclusion of the supper party, Captain Brawley, currently in command of a regiment stationed south of Limerick, had requested a private audience with the earl. Tyrell had attended, as was his right. And the young Captain had informed them that Sean O’Neill’s whereabouts had been discovered.

Shocked, they had learned that Sean had been incarcerated in a military prison in Dublin for the past two years. Their disbelief and horror growing, they were told that Sean had been charged with and tried for treason. There was no explanation for his lengthy incarceration or the failure of the authorities to hang him, much less to bring the facts forward to the family. Then Brawley had announced the most shocking news of all. Three days ago, Sean had taken the prison warden hostage and he had escaped.

Sean O’Neill was a fugitive now, wanted by the authorities, a bounty on his head.

And at any moment, Tyrell expected him to appear at Adare.

CHAPTER TWO

EVERYONE KNEW that hell was blazing fire. Everyone was wrong.

Hell was darkness. It was darkness, silence, isolation. He knew—he had just spent two years in it. Three days ago, he had escaped.

And because the light of day hurt his eyes, because everyday sounds startled and frightened him, because he was being pursued by the British and he did not intend to hang, he had been hiding in the woods by day and making his way south by night. He had been told that there were men in Cork who would help him flee the country. Radical men, men who were traitors, too, men who had nothing to lose except for their lives.

It was almost dawn. He was covered with sweat, having traveled from the prison in Dublin to the outskirts of Cork in just three nights by foot. Once he had realized he might never be let out of the black hole that was his cell, he had started to use his body to keep it strong, beginning to plan his escape. Exercising his body had been simple—he had found a ledge on the wall and he had used it to hang from or to pull up on. He had used the floor in a similar manner, pushing up until his shoulders and arms ached. He had tried to keep his legs strong by practicing fencing exercises, concentrating on lunges and squats, but his body was not used to walking or running or covering any distance at all. The muscles he had not used for two years now screamed at him in protest and pain. His feet hurt most of all.

Exercising his mind had been excruciatingly difficult. He had focused on mathematical problems, geography, philosophy and poems. He had quickly realized he must keep his mind occupied at all times—otherwise, there was thought. Thought led to memory and memory led to despair and worse, to fear. Thought was to be avoided at all cost.

In his hand, he carried a burning torch. The torch was his greatest treasure. Having been immersed in almost total darkness for two years, a source of light was as important to him as the air he breathed, or as his freedom. The torch felt as weighty in his hand as a king’s ransom. Sean O’Neill looked up at the sky as it turned a dark, dismal gray. He no longer needed the light if he dared to go on. The sole other survivor from the village of Kilvore had instructed him to proceed to a specific farm as swiftly as possible, and he knew he must go on, somehow transcending his fear. He carefully extinguished the torch.

The Blarney Road he was on was made of rough and rutted dirt, and led into the town’s center. Somewhere up ahead was the Connelly farm. He had been assured that there he would find comfort and aid.

His heart beat hard and heavily as he walked through the woods, not daring to use the roadway but keeping parallel to it. From the width of it and the wheel ruts, he saw that it was well used. In the three long nights he had been traveling, he’d avoided all roads and even dirt paths, keeping to the hills and the forest. He’d heard troops once, but that had been a hundred miles north of where he now was. Only hours from Dublin, he’d heard the cavalcade of horses and had peered out from some high rocks on a hilltop. Below, he’d seen the blue uniforms of a horse regiment. The last time he’d seen cavalry, two dozen men had died—as had innocent women and children. In real fear, he had melted back into the woods.

The sky began to turn a pale pink. Today, clearly, it would not rain. His tension began, creeping over him, a companion both familiar and despised. But he was too close to run to the ground now. He would suffer the daylight, no matter what it cost him. Already the sounds of an awakening forest were making him start and jump, the birds beginning to sing merrily from their perches in the branches overhead. As had been the case each morning since his escape, their song brought tears to his eyes. It was as precious, as priceless, as the unlit torch he carried.

The road rounded and a cottage became visible, the roof thatched, the walls stuccoed, two sows rooting in the mud in the front yard by the well. A single cleared cornfield was behind the house, a smaller lodge there.

Sean paused behind a tree, breathing hard, but not from exertion. As alert as he was, it was hard to see across the road and to the house and the hut beyond. His eyes had become so weak. He finally glimpsed a movement between the house and the field—it was a man, or so he thought. He hoped it was Connelly.

Sean looked up and down the road but saw nothing and no one. Not trusting his poor eyesight, he strained to hear. The only sound he heard was that of myriad birds, and after a moment, he also decided that he could detect a soft rustling of leaves, the whisper of a fall breeze.

He thought he was very much alone.

More sweat pooled.

His heart pumped with painful force now. He stepped from the woods and onto the road, almost expecting a column of troops to mow him mercilessly down. But not a single soldier appeared, much less an entire column. He tried to breathe more easily, but he simply could not. He was too afraid.

He blinked against the brightening sky and pushed across the road.

The man saw him and halted.

Sean cursed his vision and strode on. He tried to summon up his voice, the effort huge. Just before his solitary confinement, there had been a murder within the prison, and much mayhem had followed. He had been badly beaten, and in the riot, his throat had been cut. No physician had been sent to attend him and for a while, he had been at death’s door. He had healed, but not fully. He could no longer speak with any ease; in fact, forming each word took tiring and painstaking effort. Of course, there had been no one to speak to for two years, and once he realized that he could barely talk, he had not even tried.

Now, he forced the word from his throat and mouth. “Conn…elly?” And he heard how hoarse and unpleasant he sounded.

The man hurried forward. “Ye be O’Neill,” he said, taking his arm.

Sean was shocked by his touch, and alarmed to realize he had been expected. He flinched and jerked away from the other man. “How?” He stopped and fought for the words a child could so easily utter. “How…do…you know?”

“We got our own secret post, if ye get my meaning,” Connelly said. He was a big, burly man with a long red nose and bright blue eyes. “I been sent word. Ye better get inside.”