Полная версия

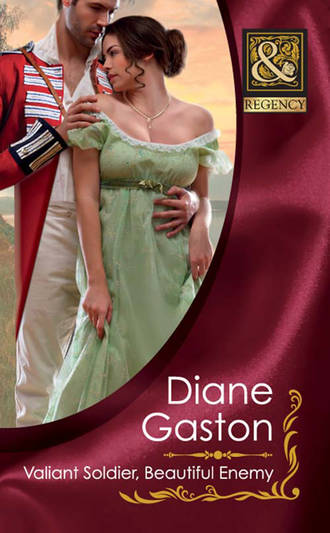

Valiant Soldier, Beautiful Enemy

A lace shop.

He opened the door and crossed the threshold, removing his shako as he entered the shop.

He was surrounded by white. White lace ribbons of various widths and patterns draped over lines strung across the length of the shop. Tables stacked with white lace cloth, lace-edged handkerchiefs and lace caps. White lace curtains covering the walls. The distinct scent of lavender mixed with the scent of linen, a scent that took him back in time to hefting huge bolts of cloth in his fatherâs warehouse.

Through the gently fluttering lace ribbons, he spied the woman emerging from a room at the back of the shop, her face still obscured. With her back to him, she folded squares of intricate lace that must have taken some woman countless hours to tat.

Taking a deep breath, he walked slowly towards her. âMadame Mableau?â

Still holding the lace in her fingers and startled at the sound of a manâs voice, Emmaline turned. And gasped.

âMon Dieu!â

She recognised him instantly, the capitaine whose presence in Badajoz had kept her sane when all seemed lost. Sheâd tried to forget those desolate days in the Spanish city, although sheâd never entirely banished the memory of Gabriel Deane. His brown eyes, watchful then, were now reticent, but his jaw remained as strong, his lips expressive, his hair as dark and unruly.

âMadame.â He bowed. âDo you remember me? I saw you from afar. I was not certain it was you.â

She could only stare. He seemed to fill the space, his scarlet coat a splash of vibrancy in the white lace-filled room. It seemed as if no mere shop could be large enough to contain his presence. Heâd likewise commanded space in Badajoz, just as he commanded everything else. Tall and powerfully built, he had filled those terrible, despairing days, keeping them safe. Giving them hope.

âPardon,â he said. âI forgot. You speak only a little English. Un peu Anglais.â

She smiled. Sheâd spoken those words to him in Badajoz.

She held up a hand. âI do remember you, naturellement.â She had never dreamed she would see him again, however. âIâI speak a little more English now. It is necessary. So many English people in Brussels.â She snapped her mouth closed. Sheâd been babbling.

âYou are well, I hope?â His thick, dark brows knit and his gaze swept over her.

âI am very well.â Except she could not breathe at the moment and her legs seemed too weak to hold her upright, but that was his effect on her, not malaise.

His features relaxed. âAnd your son?â

She lowered her eyes. âClaude was well last I saw him.â

He fell silent, as if he realised her answer hid some- thing she did not wish to disclose. Finally he spoke again. âI thought you would be in France.â

She shrugged. âMy aunt lives here. This is her shop. She needed help and we needed a home. Vraiment, Belgium is a better place toâhow do you say?âto rear Claude.â

Sheâd believed living in Belgium would insulate Claude from the patriotic fervour Napoleon had generated, especially in her own family.

Sheâd been wrong.

Gabriel gazed into her eyes. âI see.â A concerned look came over his face. âI hope your journey from Spain was not too difficult.â

It was all so long ago and fraught with fear at every step, but there had been no more attacks on her person, no need for Claude to risk his life for her.

She shivered. âWe were taken to Lisbon. From there we gained passage on a ship to San Sebastian and then another to France.â

Sheâd had money stitched into her clothing, but without the capitaineâs purse she would not have had enough for both the passage and the bribes required to secure the passage. What would have been their fate without his money?

The money.

Emmaline suddenly understood why the captain had come to her shop. âI will pay you back the money. If you return tomorrow, I will give it to you.â It would take all her savings, but she owed him more than that.

âThe money means nothing to me.â His eyes flashed with pain. Sheâd offended him. Her cheeks burned. âI beg your pardon, Gabriel.â

He almost smiled. âYou remembered my name.â

She could not help but smile back at him. âYou remembered mine.â

âI could not forget you, Emmaline Mableau.â His voice turned low and seemed to reach inside her and wrap itself around her heart.

Everything blurred except him. His visage was so clear to her she fancied she could see every whisker on his face, although he must have shaved that morning. Her mind flashed back to those three days in Badajoz, his unshaven skin giving him the appearance of a rogue, a pirate, a libertine. Even in her despair sheâd wondered how his beard would feel against her fingertips. Against her cheek.

But in those few days sheâd welcomed any thought that strayed from the horror of seeing her husband killed and hearing her sonâs anguished cry as his father fell on to the hard stones of the cobbled street.

He blinked and averted his gaze. âPerhaps I should not have come here.â

Impulsively she touched his arm. âNon, non, Gabriel. I am happy to see you. It is a surprise, no?â

The shop door opened and two ladies entered. One loudly declared in English, âOh, what a lovely shop. Iâve never seen so much lace!â

These were precisely the sort of customers for whom Emmaline had improved her English. The numbers of English ladies coming to Brussels to spend their money kept increasing since the war had ended.

If it had ended.

The English soldiers were in Brussels because it was said there would be a big battle with Napoleon. No doubt Gabriel had come to fight in it.

The English ladies cast curious glances towards the tall, handsome officer who must have been an incongruous sight amidst all the delicate lace.

âI should leave,â he murmured to Emmaline.

His voice made her knees weaken again. She did not wish to lose him again so soon.

He nodded curtly. âI am pleased to know you are well.â He stepped back.

He was going to leave!

âUn moment, Gabriel,â she said hurriedly. âIâI would ask you to eat dinner with me, but I have nothing to serve you. Only bread and cheese.â

His eyes captured hers and her chest ached as if all the breath was squeezed out of her. âI am fond of bread and cheese.â

She felt almost giddy. âI will close the shop at seven. Will you come back and eat bread and cheese with me?â

Her aunt would have the apoplexie if she knew Emmaline intended to entertain a British officer. But with any luck Tante Voletta would never know.

âWill you come, Gabriel?â she breathed.

His expression remained solemn. âI will return at seven.â He bowed and quickly strode out of the shop, the English ladies following him with their eyes.

When the door closed behind him, both ladies turned to stare at Emmaline.

She forced herself to smile at them and behave as though nothing of great importance had happened.

âGood morning, mesdames.â She curtsied. âPlease tell me if I may offer assistance.â

They nodded, still gaping, before they turned their backs and whispered to each other while they pretended to examine the lace caps on a nearby table.

Emmaline returned to folding the square of lace sheâd held since Gabriel first spoke to her.

It was absurd to experience a frisson of excitement at merely speaking to a man. It certainly had not happened with any other. In fact, since her husbandâs death sheâd made it a point to avoid such attention.

She buried her face in the piece of lace and remembered that terrible night. The shouts and screams and roar of buildings afire sounded in her ears again. Her body trembled as once again she smelled the blood and smoke and the sweat of men.

She lifted her head from that dark place to the bright, clean white of the shop. She ought to have forgiven her husband for taking her and their son to Spain, but such generosity of spirit eluded her. Remyâs selfishness had led them into the trauma and horror that was Badajoz.

Emmaline shook her head. No, it was not Remy she could not forgive, but herself. She should have defied him. She should have refused when he insisted, I will not be separated from my son.

She should have taken his yelling, raging and threatening. She should have risked the back of his hand and defied him. If she had refused to accompany him, Remy might still be alive and Claude would have no reason to be consumed with hatred.

How would Claude feel about his mother inviting a British officer to sup with her? To even speak to Gabriel Deane would be a betrayal in Claudeâs eyes. Claudeâs hatred encompassed everything Anglais, and would even include the man whoâd protected them and brought them to safety.

But neither her aunt nor Claude would know of her sharing dinner with Gabriel Deane, so she was determined not to worry over it.

She was merely paying him back for his kindness to them, Emmaline told herself. That was the reason sheâd invited him to dinner.

The only reason.

The evening was fine, warm and clear as befitted late May. Gabe breathed in the fresh air and walked at a pace as rapid as when heâd followed Emmaline that morning. He was too excited, too full of an anticipation he had no right to feel.

Heâd had his share of women, as a soldier might, short-lived trysts, pleasant, but meaning very little to him. For any of those women, he could not remember feeling this acute sense of expectancy.

He forced himself to slow down, to calm himself and become more reasonable. It was curiosity about how sheâd fared since Badajoz that had led him to accept her invitation. The time theyâd shared made him feel attached to her and to her son. He merely wanted to ensure that Emmaline was happy.

Gabriel groaned. He ought not think of her as Emmaline. It conveyed an intimacy he had no right to assume.

Except she had called him by his given name, he remembered. To hear her say Gabriel was like listening to music.

He increased his pace again.

As he approached the shop door, he halted, damping down his emotions one more time. When his head was as steady as his hand he turned the knob and opened the shop door.

Emmaline stood with a customer where the ribbons of lace hung on a line. She glanced over at him when he entered.

The customer was another English lady, like the two who had come to the shop that morning. This lady, very prosperously dressed, loudly haggled over the price of a piece of lace. The difference between Emmalineâs price and what the woman wanted to pay was a mere pittance.

Give her the full price, Gabe wanted to say to the customer. He suspected Emmaline needed the money more than the lady did.

âTrès bien, madame,â Emmaline said with a resigned air. She accepted the lower price.

Gabe moved to a corner to wait while Emmaline wrapped the lace in paper and tied it with string. As the lady bustled out she gave him a quick assessing glance, pursing her lips at him.

Had that been a look of disapproval? She knew nothing of his reasons for being in the shop. Could a soldier not be in a womanâs shop without censure? This ladyâs London notions had no place here.

Gabe stepped forwards.

Emmaline smiled, but averted her gaze. âI will be ready in a minute. I need to close up the shop.â

âTell me what to do and Iâll assist you.â Better for him to be occupied than merely watching her every move.

âClose the shutters on the windows, if you please?â She straightened the items on the tables.

When Gabe secured the shutters, the light in the shop turned dim, lit only by a small lamp in the back of the store. The white lace, so bright in the morning sun, now took on soft shades of lavender and grey. He watched Emmaline glide from table to table, refolding the items, and felt as if they were in a dream.

She worked her way to the shop door, taking a key from her pocket and turning it in the lock. âCâest fait!â she said. âI am finished. Come with me.â

She led him to the back of the shop, picking up her cash box and tucking it under her arm. She lit a candle from the lamp before extinguishing it. âWe go out the back door.â

Gabe took the cash box from her. âI will carry it for you.â

He followed her through the curtain to an area just as neat and orderly as the front of the shop.

Lifting the candle higher, she showed him a stairway. âMa tanteâmy auntâlives above the shop, but she is visiting. Some of the women who make the lace live in the country; my aunt visits them sometimes to buy the lace.â

Gabe hoped her aunt would not become caught in the armyâs march into France. Any day now he expected the Allied Army to be given the order to march against Napoleon.

âWhere is your son?â Gabe asked her. âIs he at school?â The boy could not be more than fifteen, if Gabe was recalling correctly, the proper age to still be away at school.

She bowed her head. âNon.â

Whenever he mentioned her son her expression turned bleak.

Behind the shop was a small yard shared by the other shops and, within a few yards, another stone building, two storeys, with window boxes full of colourful flowers.

She unlocked the door. âMa maison.â

The contrast between this place and her home in Badajoz could not have been more extreme. The home in Badajoz had been marred by chaos and destruction. This home was pleasant and orderly and welcoming. As in Badajoz, Gabe stepped into one open room, but this one was neatly organised into an area for sitting and one for dining, with what appeared to be a small galley kitchen through a door at the far end.

Emmaline lit one lamp, then another, and the room seemed to come to life. A colourful carpet covered a polished wooden floor. A red upholstered sofa, flanked by two small tables and two adjacent chairs, faced a fireplace with a mantel painted white. All the tables were covered with white lace tablecloths and held vases of brightly hued flowers.

âCome in, Gabriel,â she said. âI will open the windows.â

Gabe closed the door behind him and took a few steps into the room.

It was even smaller than the tiny cottage his uncle lived in, but had the same warm, inviting feel. Uncle Will managed a hill farm in Lancashire and some of Gabeâs happiest moments had been spent working beside his uncle, the least prosperous of the Deane family. Gabe was overcome with nostalgia for those days. And guilt. Heâd not written to his uncle in years.

Emmaline turned away from the window to see him still glancing around the room. âIt is small, but we did not need more.â

It seemed ⦠safe. After Badajoz, she deserved a safe place. âIt is pleasant.â

She lifted her shoulder as if taking his words as disapproval.

He wanted to explain that he liked the place too much, but that would be even more difficult to put into words.

She took the cash box from his hands and put it in a locking cabinet. âI regret so much that I do not have a meal sufficient for you. I do not cook much. It is only for me.â

Meaning her son was not with her, he imagined. âNo pardon necessary, madame.â Besides, he had not accepted her invitation because of what food would be served.

âThen please sit and I will make it ready.â

Gabe sat at the table, facing the kitchen so he could watch her.

She placed some glasses and a wine bottle on the table. âIt is French wine. I hope you do not mind.â

He glanced up at her. âThe British pay smugglers a great deal for French wine. I dare say it is a luxury.â

Her eyes widened. âCâest vrai? I did not know that. I think my wine may not be so fine.â

She poured wine into the two glasses and went back to the kitchen to bring two plates, lace-edged linen napkins and cutlery. A moment later she brought a variety of cheeses on a wooden cutting board, a bowl of strawberries and another board with a loaf of bread.

âWe may each cut our own, no?â She gestured for him to select his cheese while she cut herself a piece of bread.

For such simple fare, it tasted better than any meal heâd eaten in months. He asked her about her travel from Badajoz and was pleased that the trip seemed free of the terrible trauma she and her son had previously endured. She asked him about the battles heâd fought since Badajoz and what heâd done in the very brief peace.

The conversation flowed easily, adding to the comfortable feel of the surroundings. Gabe kept their wine glasses filled and soon felt as relaxed as if heâd always sat across the table from her for his evening meal.

When theyâd eaten their fill, she took their plates to the kitchen area. Gabe rose to carry the other dishes, reaching around her to place them in the sink.

She turned and brushed against his arm. âThank you, Gabriel.â

Her accidental touch fired his senses. The scent of her hair filled his nostrils, the same lavender scent as in her shop. Her head tilted back to look into his face. She drew in a breath and her cheeks tinged pink.

Had she experienced the same awareness? That they were a man and a woman alone together?

Blood throbbed through his veins and he wanted to bend lower, closer, to taste those slightly parted lips.

She turned back to the sink and worked the pump to fill a kettle with water. âI will make coffee,â she said in a determined tone, then immediately apologised. âI am sorry I do not have tea.â

âCoffee will do nicely.â Gabe stepped away, still pulsating with arousal. He watched her light a fire in a tiny stove and fill a coffee pot with water and coffee. She placed the pot on top of the stove.

âShall we sit?â She gestured to the red sofa.

Would she sit with him on the sofa? He might not be able to resist taking her in his arms if she did.

The coffee eventually boiled. She poured it into cups and carried the tray to a table placed in front of the sofa. Instead of sitting beside him, she chose a small adjacent chair and asked him how he liked his coffee.

He could barely remember. âMilk and a little sugar.â

While she stirred his coffee, he absently rubbed his finger on the lace cloth atop the table next to him. His fingers touched a miniature lying face down on the table. He turned it over. It was a portrait of a youth with her dark hair and blue eyes.

âIs this your son?â If so, heâd turned into a fine-looking young fellow, strong and defiant.

She handed him his cup. âYes. It is Claude.â Her eyes glistened and she blinked rapidly.

He felt her distress and lowered his voice to almost a whisper. âWhat happened to him, Emmaline? Where is he?â

She looked away and wiped her eyes with her fingers. âNothing happened, you see, but everything â¦â Her voice trailed off.

He merely watched her.

She finally faced him again with a wan smile.

âClaude was so young. He did notâdoes notâunder-stand war, how men do bad things merely because it is war. Soldiers die in war, but Claude did not comprehend that his father died because he was a soldierââ

Gabe interrupted her. âYour husband died because our men were lost to all decency.â

She held up a hand. âBecause of the battle, no? It was a hard siege for the British, my husband said. Remy was killed because of the siege, because of the war.â

He leaned forwards. âI must ask you. The man who tried to molest youâdid he kill your husband?â

She lowered her head. âNon. The others killed my husband. That one stood aside, but his companions told him to violate me.â

His gut twisted. âI am sorry, Emmaline. I am so sorry.â He wanted even more than before to take her in his arms, this time to comfort her.

He reached out and touched her hand, but quickly withdrew.

âYou rescued us, Gabriel,â she said. âYou gave us money. You must not be sorry. I do not think of it very much any more. And the dreams do not come as often.â

He shook his head.

She picked up the miniature portrait of her son and gazed at it. âI told Claude it happened because of war and to try to forget it, but he will not. He blames the Anglais, the British. He hates the British. All of them. If he knew you were here, he would want to kill you.â

Gabe could not blame Claude. Heâd feel the same if heâd watched his family violently destroyed.

âWhere is Claude?â he asked again.

A tear slid down her cheek. âHe ran away. To join Napoleon. He is not yet sixteen.â She looked Gabe directly in the face. âThere is to be a big battle, is there not? You will fight in it.â Her expression turned anguished. âYou will be fighting my son.â

Chapter Two

Emmalineâs fingers clutched Claudeâs miniature as she fought tears.

âI did not mean to say that to you.â The pain about her son was too sharp, too personal.

âEmmaline.â Gabrielâs voice turned caring.

She tried to ward off his concern. âI am merely afraid for him. It is a motherâs place to worry, no?â She placed the small portrait on the table and picked up her cup. âPlease, drink your coffee.â

He lifted his cup, but she was aware of him watching her. She hoped she could fool him into thinking she was not distressed, that she would be able to pretend she was not shaken.

He put down his cup. âMost soldiers survive a battle,â he told her in a reassuring voice. âAnd many are not even called to fight. In Badajoz your son showed himself to be an intelligent and brave boy. There is a good chance he will avoid harm.â

She flinched with the memory. âIn Badajoz he was foolish. He should have hidden himself. Instead, he was almost killed.â Her anguish rose. âThe soldiers will place him in the front ranks. When my husband was alive the men used to talk of it. They put the young ones, the ones with no experience, in the front.â

He cast his eyes down. âThen I do not know what to say to comfort you.â

That he even wished to comfort her brought back her tears. She blinked them away. âThere is no comfort. I wait and worry and pray.â

He rubbed his face and stood. âIt is late and I should leave.â

âDo not leave yet,â she cried, then covered her mouth, shocked at herself for blurting this out.

He walked to the door. âI may be facing your son in battle, Emmaline. How can you bear my company?â

She rose and hurried to block his way. âI am sorry I spoke about Claude. I did not have theâthe intention to tell you. Please do not leave me.â

He gazed down at her. âWhy do you wish me to stay?â

She covered her face with her hands, ashamed, but unable to stop. âI do not want to be alone!â

Strong arms engulfed her and she was pressed against him, enveloped in his warmth, comforted by the beating of his heart. Her tears flowed.

Claude had run off months ago and, as Brussels filled with British soldiers, the reality of his possible fate had eaten away at her. Her aunt and their small circle of friends cheered Claudeâs patriotism, but Emmaline knew it was revenge, not patriotism, that drove Claude. Sheâd kept her fears hidden until this moment.

How foolish it was to burden Gabriel with her woes. But his arms were so comforting. He demanded nothing, merely held her close while she wept for this terrible twist of fate.