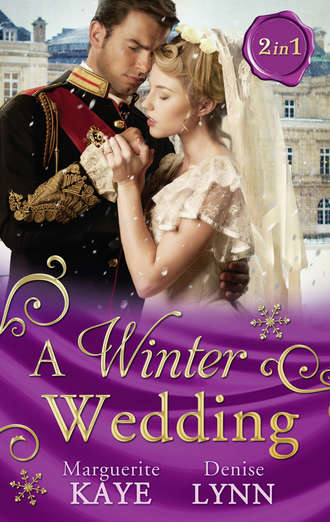

A Winter Wedding: Strangers at the Altar / The Warrior's Winter Bride

Полная версия

A Winter Wedding: Strangers at the Altar / The Warrior's Winter Bride

Язык: Английский

Год издания: 2019

Добавлена:

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента

Купить и скачать всю книгу