Полная версия

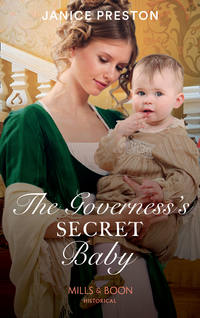

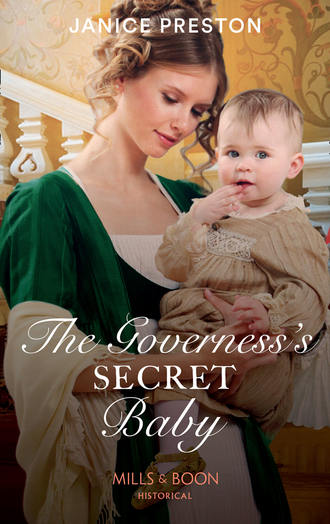

The Governess's Secret Baby

There were also very compelling reasons why he would not send Grace Bertram packing. She was pleasant and she was warm-hearted. With a young child, that must be a bonus. He refused to relinquish the care and upbringing of his two-year-old niece to a strict governess who could not—or would not—show her affection. More importantly, Clara appeared to like Miss Bertram. Besides, if he was honest, there was no one else. He had no other option. He had interviewed two women whilst he was still at Ravenwell Manor, hoping to find someone immediately. Neither wanted the job. And that other woman, Miss Browne, had not even arrived for her interview.

He eyed Grace Bertram as she faced him, head high. Despite her youth, he recognised her unexpected core of steel as she threw her metaphorical gauntlet upon the ground. She wanted to stay. Her eyes shone with determination as she held his gaze.

She does not recoil at my appearance.

She had not flinched once, nor stared, nor even averted her gaze. It was as though his scars did not matter to her.

Of course they do not, you fool. You are interviewing her for the post of a governess, not a wife or a mistress.

That thought decided him. They would spend little time together, but her acceptance of his appearance was a definite point in her favour.

‘Come,’ he said. ‘I will introduce you to Mrs Sharp and she will show you around the house.’

He swung Clara up on to his shoulders, revelling in her squeal of delight, and led the way to the kitchen, awareness of the young woman following silently at his heels prickling under his skin. He needed to be alone; he needed time to adjust. By the time they reached the door into the kitchen, his nerves were strained so tight he feared one wrong word from his housekeeper or from Miss Bertram might snap them with disastrous consequences. He pushed the door wide, ducking his knees as he walked through the opening, to protect Clara’s head. Mrs Sharp paused in the act of slicing apples.

‘Was she suitable, milord?’

Miss Bertram was still behind Nathaniel; he stepped aside to allow her to enter the kitchen.

‘Yes. Mrs Sharp—Miss Bertram.’

Mrs Sharp’s lips thinned as she looked the new governess up and down. ‘Where are your shoes?’

Nathaniel felt rather than saw Miss Bertram’s sideways glance at him. He should ease her way with Mrs Sharp, but he felt the urge to be gone. Miss Bertram must learn to have no expectations of him: he had his own life to live and she would get used to hers. He lifted Clara from his shoulders, silently excusing himself for his lack of manners. She was only a governess, after all. He would be paying her wages and providing her with food and board. He need not consider her feelings.

‘I’ll leave you to show Miss Bertram the house: where she is to sleep, the child’s new quarters and so forth.’

He turned abruptly and strode from the kitchen, quashing the regret that snaked through him at the realisation of how much less he would now see of Clara. The past few weeks, although worrying and time-consuming, had also revived the simple pleasure of human company, even though Clara was only two. She’d been restless at night and he’d put her to sleep in the room next to his, needing to know someone would hear her and go to her if she cried. Although the Sharps and Alice, the young housemaid who had travelled back with him from Ravenwell, had helped, he could not expect them to care for Clara’s welfare as he did. Now, that would no longer be necessary. A suite of rooms had already been prepared for when a governess was appointed and Clara would sleep in her new room—at the far side of the house from his—tonight.

He snagged his greatcoat from a hook by the back door and shrugged into it as he strode along the path to the barns. The dogs heard him coming and milled around him, leaping, tails wagging frantically, panting in excitement.

‘Steady on, lads,’ he muttered, his agitation settling as he smoothed the head of first one, then another. His favourite, Brack—a black-and-tan hound of indeterminate breeding—shouldered his way through the pack to butt at Nathaniel’s hand, demanding attention. He paused, taking Brack’s head between his hands and kneading his mismatched ears—one pendulous and shaggy, the other a mere stump following a bite when he was a pup—watching as the dog half-closed his eyes in ecstasy. Dogs were so simple. They offered unconditional love. He carried on walking, entering the barn. Ned, his groom, emerged from the feed store at the far end.

‘Be riding, milord?’ Ned was a simple man of few words who lived alone in a loft above the carriage house.

‘Not now, Ned. How’s the mare?’

‘She’ll do.’ One of the native ponies they kept for working the sheep that grazed on the fells had a swollen fetlock.

Nathaniel entered the stall where she was tethered, smoothing a hand down her sleek shoulder and on down her foreleg.

‘Steady, lass. Steady, Peg,’ he murmured. There was still a hint of heat in the fetlock, but it was nowhere near as fiery as it had been the previous day. He straightened. ‘That feels better,’ he said. ‘Keep on with the good work. I’m off up to the mews.’

‘Right you are, milord.’

The dogs, calmer now, trotted by his side as he walked past the barn and turned on to the track that led up to the mews where he kept his birds, cared for by Tam. There was no sign of Tam, who lived in a cottage a few hundred yards further along the track with his wife, Annie. The enclosures that housed his falcons—three peregrine falcons, a buzzard, and a kestrel—came into view and Nathaniel cast a critical eye over the occupants as he approached. They looked, without exception, bright-eyed, their feathers glossy, as they sat on their perches. He had flown two of them earlier and now they were fed up and settled.

Loath to disturb the birds, he did not linger, but rounded the enclosures to enter the old barn against which they were built, shutting the door behind him to keep the dogs out. Light filtered in through gaps in the walls and the two small, unglazed windows, penetrating the gloomy interior. A flap and a shuffle sounded from the large enclosure built in one corner, where a golden eagle—a young female, they thought, owing to her size—perched on a thick branch.

The eagle had been found with a broken wing by Tam’s cousin, who had sent her down from Scotland, knowing of Nathaniel’s expertise with birds of prey. Between them, he and Tam had nursed the bird back to health and were now teaching her to fly again. Nathaniel had named her Amber, even though he knew he must eventually release her back into the wild. His other birds had been raised in captivity and would have no chance of survival on their own. Amber, however, was different and, much as Nathaniel longed to keep her, he knew it would be unfair to cage her when she should be soaring free over the mountains and glens of her homeland.

Nathaniel selected a chunk of meat from a plate of fresh rabbit on Tam’s bench, then crossed to the cage, unbolted the door, and reached inside. His soft call alerted the bird, who swivelled her head and fixed her piercing, golden eyes on Nathaniel’s hand. With a deft flick of his wrist, Nathaniel lobbed the meat to the eagle, who snatched it out of the air and gulped it down.

Nathaniel withdrew his arm and bolted the door, but did not move away. He should return to the house. He had business to deal with: correspondence to read and to write, bills to pay, decisions to make over the countless issues that arose concerning his estates. He rested his forehead against the upright wooden slats of Amber’s cage. The bird contemplated him, unblinking. At least she wasn’t as petrified as she had been in the first few days following her journey from Scotland.

‘I know how you feel,’ he whispered to the eagle. ‘Life changes in an instant and we must adjust as best we can.’

The turning point in his life had been the fire that destroyed the original Ravenwell Manor. It had been rebuilt, of course. It was easy to restore a building—not so easy to repair a life changed beyond measure. He touched his damaged cheek, the scarred skin tight and bumpy beneath his fingertips. And it was impossible to restore a lost life. The familiar mix of guilt and desolation washed over him at the memory of his father.

And now another turning point in his life had been reached with Hannah’s death.

As hard as he strove to keep the world at bay, it seemed the Fates deemed otherwise. His hands clenched, but he controlled his urge to slam his fists against the bars of the cage—being around animals and birds had instilled in him the need to control his emotions. He pushed away from the bars and headed for the door, turning his anger upon himself. Why was he skulking out here, when there was work to be done? He would shut himself in his book room and try to ignore this latest intrusion into his life.

* * *

Grace winced as the door banged shut behind the Marquess. She tried not to resent that he had left her here alone to deal with Mrs Sharp, who looked as disapproving as Madame Dubois at her most severe, with the same silver-streaked dark hair, scraped back into a bun. Grace tried to mask her nervousness as the housekeeper’s piercing grey eyes continued to rake her. Clara, meanwhile, had toddled forward and was attempting to clamber up on a chair by the table. Grace moved without conscious thought to help her. Clara didn’t appear to be intimidated by the housekeeper, so neither would she.

‘Well? Your shoes, Miss Bertram?’

‘His lordship requested that I remove them when I came inside,’ Grace said. ‘They were muddy.’ She looked at the bowl of apples. They would discolour if not used shortly. ‘May I help you finish peeling those before you show me where my room is? I should not like them to spoil.’

Wordlessly, Mrs Sharp passed her a knife and an unpeeled apple. They worked in silence for several minutes, then Mrs Sharp disappeared through a door off the kitchen and re-emerged, carrying a ball of uncooked pastry in one hand and a pie dish in the other. As she set these on the table, she reached into a pocket of her apron and withdrew a biscuit, which she handed to Clara, who had been sitting quietly—too quietly, in Grace’s opinion—on her chair. Clara took the biscuit and raised it to her mouth. Grace reached across and stayed her hand.

‘What do you say to Mrs Sharp, Clara?’

Huge green eyes contemplated her. Grace crouched down beside Clara’s chair. ‘You must say thank you when someone gives you something, Clara. Come, now, let me hear you say Thank you.’

Clara’s gaze travelled slowly to Mrs Sharp, who had paused in the act of sprinkling flour on to the table and her rolling pin.

‘Did his lordship not say? She has barely said a word since she came here.’

‘Yes. He told me, but I shall start as I mean to go on. Clara must be encouraged to find her voice again,’ Grace said. ‘Come on, sweetie, can you say, Thank you?’

Clara shook her head, her curls bouncing around her ears. Then, as Grace still prevented her eating the biscuit, her mouth opened. The sound that emerged was nowhere near a word, it was more of a sigh, but Grace immediately released Clara’s hand, saying, ‘Clever girl, Clara. That was nice of you to thank Mrs Sharp. You may now eat your biscuit.’

She glanced at Mrs Sharp, but the housekeeper’s head was bent as she concentrated on rolling out the pastry and she did not respond. Grace bit back her irritation. It wouldn’t have hurt the woman to praise Clara or to respond to her. But she held her tongue, wary of further stirring the housekeeper’s hostility.

Once the apple pie was in the oven, Mrs Sharp led the way from the kitchen. They went upstairs first—Grace carrying Clara—then crossed the galleried landing and turned into a dark corridor, lit only by a window at the far end.

‘This is your bedchamber.’

Grace walked through the door Mrs Sharp indicated into a plain room containing a bed, a massive wardrobe and a sturdy washstand. The curtains were half-drawn across the windows, rendering the room as gloomy and unwelcoming as the rest of the house. Grace’s portmanteau was already in the room, by the foot of the bed.

‘Who brought this up?’ she asked, bending to put Clara down. The thought of the burly Lord Ravenwell bringing her bag upstairs and into her bedchamber set strange feelings stirring deep inside her.

‘Sharp. My husband.’

‘So he works in the house, too?’

‘Yes.’

Thoroughly annoyed by now, Grace refused to be intimidated by the older woman’s clipped replies.

‘His lordship mentioned three inside servants and two outside,’ she said. ‘Who else is there apart from you and your husband?’

A breath of exasperation hissed through Mrs Sharp’s teeth. ‘Indoors, there’s me and Sharp, and Alice, the housemaid. She’s only been here three weeks. His lordship brought her back with him and Miss Clara from Ravenwell, to help me with the chores.

‘Outside, there’s the men who care for his lordship’s animals. Ned is unmarried and lives in quarters above the carriage house. Tam lives in a cottage on the estate. His wife, Annie, spins wool from the estate sheep and helps me on laundry days.

‘Now, I have dinner to prepare. I don’t have time for all these questions.’ She headed for the door. ‘Hurry along. There’s more to show you before we’re finished.’

‘I shall just find my shoes.’

Her stockinged feet were thoroughly chilled again, after standing in the stone-flagged kitchen. Ignoring another hiss from the housekeeper, Grace unclasped her bag and pulled out her sturdy shoes, part of the uniform deemed by Madame Dubois to be suitable for a governess, along with high-necked, long-sleeved, unadorned gowns, of which she had two, one in grey and one in brown.

She hurried to put on her shoes whilst Mrs Sharp tapped her foot by the door. As soon as Grace was done, Mrs Sharp disappeared, her shoes clacking out her annoyance as she marched along the wooden-floored corridor. Grace scooped Clara up and followed.

‘This is the eastern end of the house,’ the housekeeper said, opening the next door, ‘which will be your domain upstairs. Your bedchamber you’ve seen, this is the child’s room—there’s a door between the two, as you can see. Then there’s a small sitting room, through that door opposite, for your own use, and the room at the far end will eventually be the schoolroom but, for now, it will be somewhere Miss Clara can play without disturbing his lordship.’

All the rooms were furnished in a similar style to Grace’s bedchamber and they felt chilly and unwelcoming as a result. Clara deserved better and Grace vowed to make the changes necessary to provide a much cosier home for her.

‘Is his lordship wealthy?’

Mrs Sharp glared. ‘And why is that any business of yours, young lady?’

Chapter Four

Too late, Grace realised how her question might be misconstrued by the clearly disapproving housekeeper.

‘No...no...I did not mean...’ She paused, her cheeks burning with mortification. ‘I merely meant...I should like to make these rooms a little more cheery. For Clara’s sake.’

Mrs Sharp stiffened. ‘I will have you know this house is spotless!’

‘I can see that, Mrs Sharp. I meant no offence. You do an excellent job.’ She would ask the Marquess. Surely he could not be as difficult to deal with as his housekeeper? ‘Perhaps you would show me the rest of the house now?’

They retraced their steps to the head of the staircase. ‘His lordship’s rooms are along there, plus two guest bedchambers.’ Mrs Sharp pointed to the far side of the landing, her tone discouraging. ‘You will have no need to turn in that direction. Alice, Sharp, and I have our quarters in the attic rooms. I will show you the rooms on the ground floor you have not yet seen and then I must get back to my kitchen. The dinner needs my attention and Miss Clara will want supper before she goes to bed.’

Grace followed Mrs Sharp to the hall below, helping Clara to descend the stairs. She bit her lip as she saw the trail of mud from the front door to where she had left her half-boots by the only chair in the hall and was thankful the housekeeper did not mention the mess. The longcase clock in the hall struck half past four as Mrs Sharp hurried Grace around the rest of the ground floor: the drawing room—as she called it—where Ravenwell had interviewed her, a large dining room crammed with furniture shrouded in more holland covers, a small, empty sitting room and a morning parlour furnished with a dining table and six chairs where, she was told, Lord Ravenwell ate his meals.

Grace wondered, but did not like to ask, where she would dine. With Clara in the nursery suite? In the kitchen with the other servants? Clara was flagging and Grace picked her up. The house was, as her first impression had suggested, sparse and cold but clean. She itched to inject some light and warmth into the place, but realised she must tread very carefully where the prickly housekeeper was concerned.

They reached the final door off the hall, to the right of the front door. Clara had grown sleepy and heavy in Grace’s arms.

‘This,’ Mrs Sharp said, as she opened the door and ushered Grace into the room, ‘is the book room.’

Grace’s gaze swept the room, lined with glass-fronted bookcases, and arrested at the sight of Lord Ravenwell, glowering at her from behind a desk set at the far end, between the fireplace and a window.

From behind her, Mrs Sharp continued, ‘It is where—oh!’ She grabbed Grace’s arm and pulled her back. ‘Beg pardon, milord. We’ll leave you in peace.’

‘Wait!’

Grace jumped at Ravenwell’s barked command and Clara roused with a whimpered protest. Grace hugged her closer, rubbing her back to soothe her, and she glared at the Marquess.

‘Clara is tired and hungry, my lord,’ she said. ‘Allow me to—’

‘Mrs Sharp. Take Clara and feed her. I need to speak to Miss Bertram.’

‘Yes, my lord.’

Grace gave her child up with reluctance, her arms already missing the warmth of that solid little body. She eyed Ravenwell anxiously as the door closed behind Mrs Sharp and Clara. His head was bowed, his attention on a sheet of paper before him.

Has he found me out? Will he send me away?

Her knees trembled with the realisation of just how much she wanted...needed...to stay.

‘Sit!’

Grace gasped. She might be only a governess, but surely there was no need to speak to her quite so brusquely. He had not even the courtesy to look at her when he snapped his order, but was directing his attention down and away, to his right. Was he still attempting to hide his disfigurement? Grace stalked over to the desk and perched on the chair opposite his.

He lifted a brow. She tilted her chin, fighting not to relinquish eye contact, determined not to reveal her apprehension. After what seemed like an hour, one corner of his mouth quirked up.

‘Did you think I meant you?’

‘I...I beg your pardon?’

‘I was talking to the dog.’ He jerked his head to his right.

Grace followed the movement, half-standing to see over the side of his desk. There, sitting by his side, was the rough-coated dog that had jumped up at her when she first arrived at Shiverstone Hall.

‘Oh.’ She swallowed, feeling decidedly foolish and even more nervous; the dog was very big and she had little experience of animals.

‘Now, to business.’ Any vestige of humour melted from Ravenwell’s expression as if it had never been and Grace recalled, with a thump of her heart, that she might have a great deal more to worry about than a dog. ‘I cannot understand how your letter applying for the post can have gone astray but, now you are here, we must make the most of it. You said this is your first post since finishing school, is that correct?’

Grace swallowed her instinctive urge to blurt out that she had written no letter of application. ‘Yes, my lord.’

‘Do you carry a reference or—?’

‘I have a letter of recommendation from my teacher, Miss Fanworth,’ Grace said, eagerly. Mayhap she was worrying about nothing. He did not sound as though he planned to send her away. ‘It is in my bag upstairs.’

‘Go and get it now, please. I shall also require the name of the principal of the school and the address.’

‘The...the principal?’ Grace’s heart sank. ‘Wh-why do you want that when I already have a letter from Miss Fanworth?’

Out of the four friends, she had been Madame Dubois’s least favourite pupil, always the centre of any devilment. You are the bane of my life, the Frenchwoman had once told Grace after a particularly naughty prank. Of course, that was before Grace had Clara—thank goodness Madame Dubois had never found out about that escapade—and Grace’s behaviour had improved considerably since then. Perhaps Madame would not write too damning a report about Grace’s conduct at school.

The Marquess continued to regard her steadily. ‘I should have thought that was obvious,’ he said, ‘and it is not for you to question my decision.’

‘No, my lord.’

Grace rose to her feet, keeping a wary eye on the dog as she did so. His feathery tail swished from side to side in response and she quickly averted her eyes.

‘Are you scared of him? Brack, come here, sir.’

Ravenwell walked around the desk to stand next to Grace and she quelled her impulse to shrink away. She had forgotten quite how tall and intimidating he was, with his wide shoulders and broad chest. He carried with him the smells she had previously noted: leather, the outdoors, and soap. Now, though, he was so close, she caught the underlying scent of warm male and she felt some long-neglected hunger within her stretch and stir. His long hair had swung forward to partially obscure the ravaged skin of his right cheek and jaw, but he did not appear to be deliberately concealing his scars now and Grace darted a glance, taking in the rough surface, before turning her wary attention once again to Brack. The dog had moved closer to her than she anticipated and now she could not prevent her involuntary retreat.

‘It is quite all right. You must not be scared of him.’

There was a hint of impatience in Ravenwell’s tone. Grace peeped up at him again, meeting his gaze. He might be intimidating in size, and brusque, but she fancied there was again a hint of humour in his dark brown eyes.

‘Try to relax. Hold out your hand. Here.’

He engulfed her hand in his, eliciting a strange little jolt deep in her core. Her pulse quickened. Ravenwell called to Brack, who came up eagerly, sniffed and then pushed the top of his head under their joined hands, his black-and-tan coat wiry under Grace’s fingers. The dog had a disreputable look about him, one ear flopping almost over his eye whilst the other was a ragged stump. Grace swallowed. Ravenwell wouldn’t keep a dangerous animal indoors. Would he?

‘All he wants is some attention,’ Ravenwell said, his warm voice rumbling through her.

Grace’s chest grew tight, her lungs labouring to draw air.

‘Where are the other dogs?’

‘Brack’s the only one who is allowed inside.’ Ravenwell released Grace’s hand and moved away, and Grace found she could breathe easily again. ‘I reared him from a pup after his mother died.’

Grace stroked along Brack’s back, feeling very daring. ‘I am sure I will get used to him.’

She imagined telling the other girls about this: how they would laugh at her fear of a simple dog. Then, with a swell of regret and sorrow, she remembered she would never again share confidences with her friends. They could write, of course, but letters were not the same as talking face to face—sharing their hopes and fears and whispering their secrets as they lay in bed at night—or as supporting and comforting each other through the youthful ups and downs of their lives. And those friends, her closest friends—her dearest Joanna, Rachel, and Isabel—had supported and comforted Grace through the worst time of her life. Theirs had been the only love she had ever known.

She longed to hear how they all fared in their new roles as governesses and she knew they would be waiting to hear from her—wondering if she had found the baby she had vowed to trace. But they would not know how to contact her—none of them, no one from her former world, knew where she had been since she left the school or where she was at this moment in time.