Полная версия

Unlocking the Bible

Most lessons we learn from Numbers are negative. This is how not to be the people of God! Paul tells us how we should view it in 1 Corinthians 10: ‘Now these things occurred as examples to keep us from setting our hearts on evil things as they did … These things happened to them as examples and were written down as warnings for us, on whom the fulfilment of the ages has come.’ Numbers is full of bad ‘examples’.

Context

What, then, is the context for this book? The journey from Mount Sinai to Kadesh Barnea (the last oasis in the Negev Desert) and the beginning of the Promised Land of Canaan takes 11 days on foot. The route the Israelites took was to turn away from Kadesh and go across the Rift Valley, to the mountains of Edom. They finished up in Moab on the wrong side of the River Jordan. It took 38 years and a few months, not because it was a particularly difficult piece of country but because God only moved a little at a time. He stayed a very long time in each place and told them he would wait until every man among them was dead, except Joshua and Caleb.

What happened to bring God’s judgement down on the people? At Kadesh the people refused to enter the land when God told them to. Today many Christians have been brought out of sin but have not enjoyed the blessing that God has set out for them. They too end up in a miserable wilderness.

Two-thirds of the book of Numbers is about this protracted journey. The Bible is a very honest book, telling us about failures and vices as well as great successes and virtues. When Paul told the Corinthians that Numbers was written down as an example and a warning to us, he meant this as a clear statement of the book’s purpose. It may not be a popular book, but if you do not study history you are condemned to repeat it.

Even Moses was not permitted to go into the Promised Land, although he did enter it centuries later when he talked with Jesus. He too failed miserably at one crucial point, as we shall see.

Content and structure

Another of the five books of Moses, Numbers is a mixture of legislation and narrative. The author of the laws is not Moses but God. We are told 80 times in this book, ‘God said to Moses…’ God gives to Moses general laws and legislation, as well as regulations governing rituals and religious ceremony.

As for the narrative in the book, we are told that Moses kept a journal of their travels at the Lord’s command. He also kept another book called ‘the book of the Wars of the LORD’, recording accounts of the battles. Numbers was written by Moses using these records, yet Moses himself is referred to in the third person

The mixture of narrative and legislation makes it seem rather like Exodus, but whereas in Exodus the first half is narrative and the second half law, in Numbers it is all mixed up. It is therefore much harder to find a connecting thread.

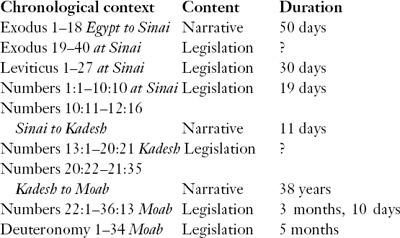

A pattern emerges more easily when we consider the narrative and legislation in context. The structure of the book is chronological rather than topical. We can see this best by putting the content of Numbers alongside that of Exodus, Leviticus and Deuteronomy.

It is fascinating to note that all the laws were given to the Israelites while they were camped. The stories of their travels show how they broke those laws. While they were camped and stationary God told them what they should do, but while they were moving we hear the story of what they did do. They would learn lessons both ways, through the teaching from Moses and through the experience of journeying (rather as Jesus taught his disciples both in ‘messages’, such as the Sermon on the Mount, and as they travelled ‘along the way’).

The chart given above is like a multi-layered sandwich. Thus in Exodus 1–11 the Israelites are stuck in Egypt, then in Chapters 12–18 they move to Sinai. All this is narrative. However, in Exodus 19–40, Leviticus 1–27 and Numbers 1–10 they are still at Sinai. These three consecutive sections are full of legislation.

In Numbers 10–12 they move again, from Sinai to Kadesh, a journey of 11 days. The stay in Kadesh covers the crisis when the people rebel. God speaks to them at Kadesh from Chapters 13 to 20, again with legislation.

Numbers 20–21 covers the journey from Kadesh to Moab, the whole journey of 38 years covering just two chapters. Numbers 22–36 covers what God said to the Israelites while they waited to go into the Promised Land. The whole of Deuteronomy 1–34 belongs to that same, stationary time period.

Numbers has a lot of movement in it, Deuteronomy has none, and Exodus has movement in just the first half.

Legislation

As noted above, we are told on 80 occasions in Numbers that God spoke to Moses ‘face to face’. This was unique: others would receive God’s Word through visions when they were awake or dreams when they were asleep. The people would consult the priests’ urim (the equivalent of ‘drawing lots’) when they wished to discern God’s mind on a situation.

Moses first met with God on Mount Sinai, some distance from the rest of Israel, but now that the tabernacle was constructed God was dwelling with the people. The big danger now that God was ‘with them’, however, was that they might become overfamiliar, lose their sense of awe and respect, and forget his holiness. The laws in Numbers are not moral or social laws, but laws given to prevent the people from losing their reverence for God. The laws can be classified under three headings: carefulness, cleanliness and costliness.

1. Carefulness

WHEN CAMPED

They had to be very careful to camp in the right place (Chapter 2). Each tribe was allotted a specific place in relation to the other tribes and the tabernacle in the centre. The camp looked like a ‘hollow rectangle’ from above (see the chart below). The only other nation known to camp in this manner were the Egyptians – this was the preferred arrangement of Rameses II (the Pharaoh who may have been on the throne at the time).

The tabernacle in the centre was surrounded by a fence and there was only one entrance. Two people camped outside the entrance – Moses and Aaron. The Levites camped around the other three sides, and three of their clans had special responsibility – Merari, Gershon and Kohath. No one else could even touch the fence and there were orders to kill anyone who approached. God was holy and could not be approached lightly.

The other tribes were arranged around the tabernacle, each tribe with its own specific, allotted place in relation to God’s tent and the entrance to it. The most important place was right in front of the entrance, and this was occupied by the tribe of Judah. It was from the tribe of Judah that Jesus would later come.

WHEN TREKKING

When the camp set out on a journey, everyone moved according to a fascinating pattern. There were specific instructions for the dismantling and transporting of the tabernacle. The priests would wrap up the holy furniture, then the Levites would pick it up. Everyone knew who had to carry which piece of furniture from the tabernacle, who had to carry the curtains, and what order they had to be carried in. Some tribes had to leave before the tabernacle pieces were carried. When the other tribes moved they ‘unpeeled’ like an orange. They marched in the same order every time, so that when they got to the next camp it was simple for each tribe to find their place and put their tents up. The whole thing is carefully detailed. The silver trumpets would sound to announce the departure from the camp, and the tribe of Judah would lead the procession with praise

They always knew when it was time to move because the pillar of cloud (or fire at night) above the tabernacle would move on. The picture is clear: when God moves, his people move.

Why is God so fussy about all these details? Not only was it a very efficient way to move such a vast quantity of people, but it was also a very efficient way of camping. He was saying, ‘Be careful!’ A careless attitude does not have a place in God’s camp: carelessness is a dangerous thing. A modern word for this would be ‘casualness’, the ‘any old thing will do for God’ attitude.

In these detailed directions God is telling his people to be careful, for he is in the camp with them. He also outlines other areas where they would need to be careful. There are some sins mentioned in Numbers which are sins of ‘carelessness’. Carelessness on the Sabbath was punishable by death. They were to have tassels on their clothes to remind them to pray. Vows had to be taken very seriously. If a vow was made to God it must be kept. (In Judges we have the story of a man who vowed to sacrifice to God the first living thing that he met when he came out, and he met his daughter!) If a wife makes a vow to God, then her husband has 24 hours to agree or disagree with it.

2. Cleanliness

As well as being carefully arranged, the camp had to be spotlessly clean, for these were ‘God’s people’. Even such things as the sewage arrangements were carefully detailed. They were told to take a spade when emptying their bowels so that they could keep the camp clean for the Lord. He was not just concerned with germs. God was interested in a ‘clean’ camp because he is a ‘clean’ God. The principle still holds today. A dirty, uncared-for church building is an insult to God.

Not only was the camp to be clean, we are also told of the cleansing of the people before they left Sinai.

There are further details of purification rites in Chapter 19. Death is an unclean thing. God is a God of life, so there was to be no taint of death in the camp. There was even a ‘jealousy test’ for adulterous wives. Even if there were no witnesses, God sees what happens and will punish the evildoer. This is his camp.

The expression ‘cleanliness is next to Godliness’ has some considerable support from the book of Numbers!

3. Costliness

SACRIFICES AND OFFERINGS

It is costly for a sinful person to live close to a holy God. Sacrifices were offered on behalf of the people on a daily, weekly and monthly basis. There were literally hundreds. Each sacrifice had to be costly – only the best animals were offered.

The daily sacrifice, weekly sacrifice and a special monthly sacrifice made it clear it was a costly matter to receive forgiveness from God. Blood had to be shed.

PRIESTHOOD

Furthermore, the priesthood had to be supported by means of offerings. The Levites were consecrated for service before they left Sinai. Some 8,580 served (out of the 22,000 in the tribe) and both priests and Levites were dependent on the other tribes for their financial support.

The upkeep of the priesthood, plus the regular sacrifices, therefore made up a considerable ‘cost’ to the people.

This teaches us that we still need to be very careful today about how we approach God. I may not need to bring a ram, pigeon or dove to be sacrificed when I come to God, but that does not mean I do not have to bring a sacrifice at all. There is as much sacrifice in the New Testament as in the Old. We read of the sacrifice of praise and the sacrifice of thanksgiving, for example. We need to ask ourselves whether we do make sacrifices to God. We too should prepare for worship.

Numbers also tells us about the Nazirite vow, a voluntary vow of dedication and devotion to God, although not part of the priesthood. The Nazirites vowed not cut their hair, not to touch alcohol (both were contrary to the social custom of the day) and not to touch a dead body. Some of these vows were temporary, others were for life. Samuel and Samson are the best-known Nazirites in Scripture. By the time of Amos the practice was ridiculed.

WHAT CAN WE LEARN FROM THIS?

Today there is a tendency towards an anti-ritual, casual approach to worship, forgetting that God is exactly the same today as he was then. We too are to approach him with awe and dignity. Hebrews reminds us that he is a consuming fire.

In the New Testament we read of how those gathered for worship may bring a song, a word, a prophecy, a tongue, an interpretation. This is the New Testament equivalent of preparing, approaching God in the right frame of mind.

Numbers also reminds us that we must worship God according to his taste and not ours. Modern worship tends to focus on the preferences of individuals, whether this be in favour of hymns or choruses, for example. We can forget that our preferences are quite irrelevant compared to the importance of making sure that our worship matches what God wants.

Our sacrifices of praise and giving are also mentioned in the New Testament: ‘They [your gifts] are a fragrant offering, an acceptable sacrifice, pleasing to God.’ In Leviticus and Numbers God loved the smell of roast lamb. In the same way, our sacrifice of praise can also be pleasing to God today.

Narrative

In turning to the narrative parts of Numbers, we move from the divine word to human deeds – from what the people should do to what they did do. It is a sad and sordid story. The wilderness becomes a testing ground for them. They are out of Egypt but not in the Promised Land, and this limbo existence is very hard for them to endure.

We need to remember that the people are now in a covenant relationship with God. He has bound himself to them. He will bless their obedience and punish their disobedience. The same acts of sin are committed in Exodus 16–19 as in Numbers 10–14, but only in Numbers is the law violated, so only in Numbers do the sanctions apply.

God’s law can help you see what is right (and wrong), but it cannot help you do what is right. The law did not change their behaviour: it brought guilt, condemnation and punishment. This is why the law given on the first Pentecost day was inadequate and later needed the Spirit to be given on that same day. Without supernatural help we would never be able to keep the law.

Leaders

We will look first at the leaders of the nation and see how they tried and failed to live up to the law. They are all from one family, two brothers and a sister – Moses, Aaron and Miriam (the Hebrew version of the name Mary). We are told their good points and their strengths of character as well as their weaknesses.

STRENGTHS

Moses

Moses is the dominant figure throughout the book. In many respects he was a prophet, a priest and a king.

We have seen already how other prophets were given visions and dreams, but Moses spoke face to face with God in the tabernacle. He was even allowed to see a part of God – he saw his ‘back’.

He also acted in the role of priest. There are five occasions when he interceded with God. Indeed, on occasions he was quite bold in the way he prayed for the people and urged God to be true to himself.

He was never called ‘king’, and of course this was some centuries before the monarchy was established, but he led the people into battle and ruled over them, and so functioned as a king, even if the title was not used.

One of the most notable things about Moses was that when he was criticized, badly treated or betrayed he never tried to defend himself. Writing about himself, he says he was the meekest of all the men on the earth – a hard thing to say if you want it to remain true! Of course, Moses was saying no more than Jesus when he said we should learn from him for he was meek and humble. Moses let the Lord defend him. Meekness is not weakness, but it does mean not trying to defend yourself.

Aaron

Aaron was Moses’ brother, assigned to Moses as his ‘spokesman’ when Moses had to face the Pharaoh in Egypt. He too was a prophet. He was also designated to be a priest, the chief priest. The Aaronic priesthood became the heart of the worship and ritual of the ancient people of God.

Miriam

Miriam was Moses’ and Aaron’s sister. She was known as a prophetess. She sang and danced with joy when the Egyptians were drowned in the sea.

So we have Moses as prophet, priest and king, Aaron as prophet and priest, and Miriam as prophetess. Note that the gifts are shared and that prophecy is a ministry for women as well as for men. Miriam’s particular prophetic gift was expressed in song. There is a very direct link between prophecy and music. In later years King David chose choirmasters who were also prophets, and Ezekiel would often request music as a preparation for his prophesying. It seems that there is something about the right kind of music which releases the prophetic spirit.

Despite their strengths and gifts, however, each of these leaders failed in some way. It is instructive for us to examine their failings in detail.

WEAKNESSES

Miriam

Miriam’s problem was jealousy: she desired honour for herself. She wanted to speak with God as Moses did. In addition she was critical of his choice of wife. Miriam was punished with ‘leprosy’ for seven days until she repented. She was among those who died at Kadesh.

Aaron

The next to drop out of the leadership picture was Aaron. Once again his problem was jealousy and desire for honour. Miriam and Aaron were together in criticizing Moses. Their excuse was that Moses had married someone of whom they did not approve (he married a Kushite woman who had come out of Egypt with them and who was not even a Hebrew). God did not criticize him for doing that, but Miriam and Aaron did.

Aaron thus died at Mount Hor, a little further on from Kadesh, when he was over 100 years old. Soon after they expressed jealousy and desire for honour, both Aaron and Miriam died.

Moses

Even Moses failed. He became very impatient with the people. The New Testament tells us that he put up with the people for 40 years in the wilderness. It was an amazing task of leadership to deal with over 2 million people who were always grumbling, complaining and having arguments that needed to be settled.

His big mistake came when he disobeyed God’s instructions concerning the provision of water. Moses had provided water for the people by striking the rock with his rod. The limestone of the Sinai Desert has the peculiar property of holding reservoirs of water within itself. There are huge reserves of water in the Sinai Desert, but they are usually surrounded by rock and contained within the rock. Moses had released those reservoirs of water just by touching the rock with his rod.

On this second occasion when they were short of water God told Moses not to strike the rock but just to speak to it. A word would be sufficient to release the water in the rock. But Moses was so impatient with the people that he did not listen to God carefully and he struck the rock twice. God told Moses that because he was disobedient, he would not put a foot in the Promised Land. This is a poignant reminder of how important it is for a leader to listen carefully to God. Moses died at Mount Nebo in sight of the Promised Land, but unable to enter it.

Numbers tells us that it is a big responsibility to lead God’s people. It must be done correctly and it must be done God’s way.

Individuals

There were a number of individuals who let God down throughout the book of Numbers. The most outstanding was a man called Korah. We find Korah leading a rebellion because he was angry that the priesthood should be exclusively the right of Aaron and his family. Others joined him in this subversion, and soon there were 250 gathered together, challenging the authority of Moses and the priesthood of Aaron. The rebels said they could not believe that God had chosen Moses and Aaron and were critical of their failure to lead the Israelites into the Promised Land.

Then with great drama, Moses told the people to keep away from all the rebels’ tents. Fire came down from heaven, struck their tents and destroyed them all. Korah saw it coming and ran away with a few of his followers, but they were swallowed up on some mudflats. (In the Sinai Desert there are mudflats which have a very hard crust but are very soft underneath, like thin ice on a pond. They are like a treacherous swamp or quicksand.)

Despite all this, some of the psalms are written by the sons of Korah. This man’s family did not follow him in his rebellion, and his children later became singers in the temple. We do not need to follow our parents when they do evil.

Korah is mentioned in the book of Jude in the New Testament as a warning to Christians not to question God’s appointments and become jealous.

Moses then announced that they needed to test whether God had chosen him and his brother for these positions. He told the leaders of the twelve tribes to get hold of twigs from the scrub bushes in the desert. They were to lay these twigs in the holy place before the Lord all night. In the morning Aaron’s stick had blossomed with leaves, flowers and budding fruit. The other twigs were dead. From then on they put Aaron’s rod inside the ark of the covenant as God’s proof that Aaron was his choice and not self-appointed.

People

The people as a whole were problematic, as well as some individuals. Acts tells us that God endured their conduct for 40 years in the wilderness. Numbers says that the whole people failed except for two – two out of more than 2 million, not a high proportion. The people had one general problem and failed on three occasions of particular note.

GRUMBLING

The general problem with the people was ‘grumbling’. You need no talent to grumble, you need no brains to grumble, you need no character to grumble, you need no self-denial to set up the grumbling business. It is one of the easiest things in the world to do.

The people thought that because God was in the tabernacle, he did not know what they said when they went to their own tents. What a big mistake! They grumbled about the lack of water, they grumbled about the monotonous food. It says they grumbled because they could not have garlic, onions, fish, cucumbers, melons and leeks as they had in Egypt. God heard their grumbling and responded accordingly. Soon he sent them quails to supplement their diet of manna – so many that they lay 1.5 metres thick, covering 12 square miles of ground! The people went out to gather the quail, but while they were still eating the meat, God struck them with a severe plague because they had rejected him.

Grumbling probably does more damage to the people of God than any other sin.

OASIS OF KADESH

The first particular occasion for failure was when they arrived at the last oasis, 66 miles south-west of the Dead Sea (today called Ain Qudeist) in the Negev Desert. They were told to send 12 spies, one from each tribe, to spy out the land and return to tell the whole camp what it was like. They spent 40 days in the south around Hebron and also travelled up to the far north, and they found it a very fertile land. But the conclusion of their report was negative. They spread the rumour that the land would devour them. They would rather go back to Egypt.

Two of the spies, Joshua and Caleb, said that God was with them and there was nothing to fear. They agreed that the land was well fortified and that it was inhabited by much bigger people. We know from archaeology that the average height of the Hebrew slaves was quite small compared to the Canaanites. They agreed too that the walls around the cities provided an obstacle. But they argued that God had not brought them this far to leave them in the desert. They told the people that God would carry them on his shoulders (just as a small boy might feel like a giant on the shoulders of his father).

The pessimistic arguments of the other 10 spies were more persuasive, however. The crowd actually wanted to stone Moses and Aaron for bringing them all this way. It had been just three months since they had left Egypt, but they were prepared to kill Moses and Aaron for bringing them out of slavery! They preferred to trust in what the 10 spies saw and said. They took the majority verdict, which in this case was contrary to God’s intentions.

The contrast in the two reports is remarkable. The 10 men said they were not able to take the land and that was that; Joshua and Caleb said, ‘We can’t, but God can’. This was not merely positive thinking but a willingness to see the problems as opportunities for God.