Полная версия

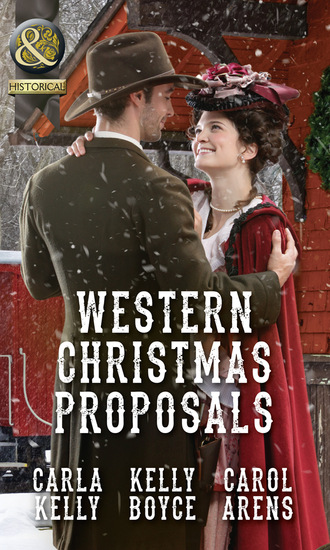

Western Christmas Proposals

“What sort of work do you need help with, Mr. Bradley?” she asked, when he came to the end of the list.

“Simple stuff—stocking the shelves, sweeping out, keeping things tidy,” he said. He rang up the total. “Fifteen dollars. I’ll box these and get them out to the buckboard.”

“Are you thinking of bailing out?” he asked as they carried the boxes to the buckboard. “Need a job?”

They walked back to the store together. “No, sir, I promised I would help out and I don’t go back on my word.”

“Why are you interested?”

“I’m asking for Pete Avery,” she said. “Mr. Bradley, Pete doesn’t like ranch work, and he can do all those things you listed.” She clasped her hands together and gave the merchant her kindest smile. “He would feel so useful, and he would be dependable.”

“I don’t know,” Mr. Bradley said, and she heard all the doubt in his voice.

“Could you think about it?” she asked.

“Think about what?”

Startled, she turned around to see Ned standing in the doorway. As she looked at him, her confidence dribbled away. It was probably a stupid idea anyway.

“Your chore girl here is wondering if your brother might be a good store clerk,” Mr. Bradley said, pointing to the help-wanted sign.

Ned stared at the sign, then glared at Kate. “There’s no need to joke about Pete.”

“I’m not joking,” she replied, stung by the disbelief in his voice. “Pete can put cans on shelves. He can sweep and tidy up. He’s polite, and I’ll wager he knows a lot of people here in Medicine Bow.”

“He doesn’t need to work here.” Ned turned away to count out the money he owed. “Unlike you, the Averys aren’t charity cases.”

That stung. Kate felt the familiar prickle of tears behind her eyes. Some imp made her keep talking. “He can do this work, and you know how he feels about riding fence.” She turned to Mr. Bradley, who was watching the two of them with real interest. “If you hire Pete, is there a place he could stay?”

“Right here. There’s a little room off the storeroom,” he said, for some reason taking her side. “I can tell you I wouldn’t mind having someone down here at night. He could eat upstairs with us.”

“It’s out of the question,” Ned replied, but he sounded neither determined nor irritated now.

“Why?” Kate asked softly. “Pete can work and earn money, same as you and me.”

“I’m liking this idea more and more,” Mr. Bradley said. “Why not try? If it doesn’t work after a week or so, we’ll know.” The merchant turned the force of his enthusiasm on Ned. “Your ma used to tell my wife that all she wanted was for Pete to have a chance at something. What could be better than this? He knows Millie and me. Hell, Pete knows everyone in town! What do you say?”

“Just don’t say no so fast, Ned,” Kate urged. “Can we think about it?”

“We?” Ned asked, exasperated again.

You’re not going to make me angry, she thought. She took a deep breath. “Yes, we. If Pete goes to work here, we’ll have to work a little harder to take care of your father.”

“You don’t mind?” Ned asked, and she knew she had him.

“Of course not. Nothing changes for me. You’re the one who won’t have any extra help outside.”

Ned sighed. “As it is, with Pete I’m dragging around a boat anchor. He’d rather do anything than get on a horse and ride all day.”

“There you are,” Mr. Bradley said cheerfully.

Silence for a moment, as Ned looked from her to the merchant and back. “All right. I’ll bring him to town tomorrow and we’ll try it for a week.”

“Shake on it?” Mr. Bradley asked, holding out his hand.

They shook hands, and Kate wanted to do a two-step around the pickle barrel.

Mr. Bradley beamed at them both. “Your chore girl and I loaded the food in the buckboard. Millie and I will tidy that little room tonight. Bring Pete by anytime before noon, will you?”

“You got me,” Ned told Katie after he helped her into the buckboard and went around to his side.

“I saw the sign and thought of Pete,” she said simply, determined not to apologize for a good idea acted upon.

He didn’t say anything for half the journey home, and then he started to chuckle. Kate felt the tension leave her shoulders.

“We’ll try it out,” he told her. “Pete used to milk the cow morning and night. You up for that?”

“If you’ll remind me how. It’s been years.”

“My pleasure.” He started on his tuneless whistle that she was already familiar with. She relaxed some more when Pete met them at the front door—the only door—of the worst place she had ever lived. Funny that she was already thinking of it as home.

Chapter Ten

Katie gave Ned credit for impressive self-control that night when Pete kept asking every few minutes if he was really going to work in town for Mr. Bradley. He asked it from the stew to the muffins, and only stopped when Ned told him to put a lid on it or he would take it all back.

Reasoning that he hadn’t made any promises to Katie, Pete then asked her over and over, when he was supposed to be teaching her to milk the cow, a rangy little number that didn’t appear to suffer fools gladly, if all those looks she gave Kate were any indication.

“Pack your clothes in that old carpetbag of Pa’s,” Ned said finally. “And don’t drive Pa nuts!” he called after his brother.

“I should have just stuck him in the buckboard tomorrow and told him on the way to town,” Ned grumbled to Kate. He sat down beside her on the stool and nudged her over. He told her to watch him milk and she did, aware of how close he sat and that he smelled of hair oil.

“You got your hair cut,” she said. “I was hoping you didn’t spend all that time in the Watering Hole,” she teased.

He gave her another nudge, which sent her off the stool and frightened the patient mama cat waiting for her turn.

“Beg your pardon,” he said in mock contrition, but he moved over a little and she sat again. “Put your hands beside mine.”

She wondered if she should tell him she had milked cows when she was a little girl. Her step pa had hit her when she didn’t do a good job, but Ned Avery didn’t need to know that.

“You try it now,” he directed.

She did as he said and he watched her. For one small moment, that same irrational fear came over her, but the ending was different this time.

“You’ll do,” he said, and touched her shoulder. He returned to the other side of the barn and finished his chores. He carried the bucket of milk into the house when she finished and told her that his father wanted to see her.

“Don’t look so worried,” he exclaimed.

“My step pa used to beat me when I didn’t do chores the way he wanted,” she told him, embarrassed to admit it, but wanted him to understand her own fear.

“That will never happen here,” he said quietly, then stopped so suddenly that the milk slopped over a little. “In fact, I know something about you that you probably don’t even realize.”

“What could that possibly be?” she asked, half amused, half wary.

“I’ve thought about this while I was riding fence,” he began, shaking his head. “Riding fence is so boring that my flights of fancy sometimes amaze me!” He turned serious then. “You’ve told me what you’ve been through at the hands of a very bad man.”

Even when he said no more, she understood what Ned wanted. “Are you wondering why I agreed to work for you?”

“I’m wondering more than a little. How did you know I wasn’t a bad man, too? You didn’t even know my name.”

They stood there in the empty space between the barn and the house, no one else in sight, the sky dark, snow threatening. She did not know how he would feel about her answer, but it was the only one she had. “Something about you told me I could trust you,” Kate said finally. She thought some more. “You didn’t crowd me. You just stood there so respectful, your hat in your hand.”

“Pa says I’m too serious. He says ladies want someone exciting.”

Katie shook her head. “Not me! Something told me I could trust you.”

He followed her into the kitchen, setting the milk into pans and covering it with a clean cloth. Tomorrow she would skim off the cream and add it to the cream of the day before. In another day she would churn it. She had found a small glass rose, stuck in that same cabinet with the calving rope, that she intended to press into the still soft butter to make a decoration.

“I should have asked you before I promised Pete to Mr. Bradley,” she said.

“Maybe, maybe not. Just thinking of that conversation embarrasses me,” he said. He sat down at the table and patted the chair beside him. “You notice how quick I was to say no, without even thinking?”

“I noticed,” she told him, “but you make the decisions.”

“No excuse for not considering something before I shut it down,” he said. He touched her hand lightly. “Thank you for not giving up on a good idea that I probably would have strangled at birth.”

She couldn’t help but feel flattered. “Everyone is taking a chance with this idea.”

“Glen Bradley will let me know if it’s not working,” he said. He gestured down the hall. “Pa wants to talk to you. Want me in there, too?”

Pride nearly made her say no, but as Katie looked into his eyes, she saw the kindness there. “I do,” she whispered.

Mr. Avery told her to take a seat and she did, pulling up the one chair in the room until it was closer to his bed. Ned stood behind her chair, his hands on the back of it.

“Ned, I’m not going to scold her,” Mr. Avery said. “You can leave.”

She was too embarrassed to look around, but heard Ned’s laugh as he backed out of the room. He didn’t go far, because she heard the rustle of his mattress in the next connecting room.

“You did a good thing for Pete,” Mr. Avery told her. “None of us knew what to do, but you did.”

“I got lucky,” she managed to say.

“It’s more than that,” he contradicted. “You’re looking out for Pete, same as we are, but you’re looking at him from a different angle. Thank you.”

“You’re welcome,” she said simply.

He motioned her to lean closer. She did.

“My other boy needs to find a wife,” he whispered. “He’s thirty-one. Got any good ideas for him?”

Kate felt her face grow hot. “Surely he can find a wife by himself,” she whispered back.

“He hasn’t so far,” Dan said. “Think about it and do what you can. I’m going to sleep now. Good night.”

Laughing inside, despite her embarrassment, Kate stood up and went to the door. Dan called her back. “I’m getting a window tomorrow. You mentioned that to him, didn’t you?”

“I did, Mr. Avery. When will he do it?”

“As soon as he gets back from dropping off Pete.” Mr. Avery smiled at her, and her heart turned over. “’Cept for finding a wife, he’s a prompt fellow. Good night, now.”

Chapter Eleven

Ned got Pete to town, gave him all sorts of admonition and advice that probably rolled right off his back, if the amused look Mrs. Bradley gave him was any indication.

“We’ll watch out for Peter,” she said as they stood on the sidewalk. “You’ve been a good brother, but he’s growing up and needs duties of his own.”

It always rolled around to duty, he thought, on the ride home, after purchasing a pane of glass at the lumberyard and anchoring it safely between two-by-fours. He’d had this conversation with himself before, especially during hard times. To his gratification, there wasn’t much sting to this duty. Pa wanted a window and he could install one. He’d have to ask Kate if he could borrow her room for Pa, because he doubted he had time to finish the window today, what with winter bringing darkness so much sooner.

He could put Kate in his room and he could bundle up and sleep in Pa’s bed for the one night it might take him to finish the little project and caulk the new window against the bitter winter headed their way soon. Ned knew the doctor had warned Pa not to exert himself at all, but the more he thought about that injunction, the more he wondered about it. Sure, Daniel Avery’s battered heart might last longer if he never did anything more strenuous than sitting up, but to what end?

He wanted to mull it all around with Katie Peck, and see what she thought about helping Pa walk down to the kitchen, or maybe even outside. One of the more pleasant byproducts of his impulsive hiring of her was the discovery that behind her solemn face was a sensible brain.

He glanced at the two-story Odd Fellows Hall as he crossed the tracks and rode south toward home, wondering if Katie knew a few dance steps. Mrs. Bradley had mentioned a dance there in mid-December and asked, “Who are you saving yourself for, Edward Avery?”

He was saving himself for no one and he thought Katie might help. She was a woman and she could probably dance. Would it hurt to ask for help?

As he passed through the gate onto Avery land, Ned’s thoughts took him in another direction, one that surprised him. For years, Pa had promised Ma a real house. Once she died, Pa had lost interest. Just thinking of a house instead of a log cabin made Ned stop at the top of the little rise and stare down at his home. The logs were stripped of bark now, the result of hungry deer and elk during many a bleak midwinter. He’d been meaning to paint the door, and even had the paint to do it, but hadn’t bothered.

It was time for a real house. He’d humor Pa by putting in a window so he could see a sampling of Avery land through it, but maybe in the spring he could draw up some plans. Kate would probably have good ideas.

With the buckboard driven into the open-sided wagon lean-to, and his horse rubbed, grained and watered, Ned went inside, sniffing appreciatively. Kate had a way with beans, beef and onions. He served himself a bowl of stew. Kate had found the ceramic bowls from somewhere and retired the tin cups.

He heard laughter as he walked down the hall, bowl in hand. He saw his copy of Roughing It in Kate’s lap, and wondered how it was that a quiet mill girl from Maine knew just how to handle his father. He sat on the edge of Pa’s bed and ate as she finished the chapter.

“One chapter left,” she said. “What will we do then?”

“I’ll find you another book,” he promised. “Got one somewhere.”

She held out her hand for his now empty bowl and he shook his head. “I can probably struggle all the way back to the kitchen with this.”

“I’m the chore girl,” she reminded him.

Suddenly, as if some cosmic hand had flicked his dense head with thumb and forefinger, he knew she was more than that; Katie Peck was a friend. He wondered if she felt his friendship. Never mind. He had all winter to figure it out.

When Ned returned to Pa’s bedroom, he outlined his ideas for the window.

Between the two of them, they helped Pa walk the short distance to Kate’s room. He was breathing heavy from the mere steps from one room to the other, and Ned felt his own heart sink.

Ned watched his father until his color returned and his breath became less labored. “I need Kate to help me with this window. Rest now.”

Pa nodded and closed his eyes. Ned stood looking down at his father, remembering earlier days and wishing for them like a child. Kate touched his shoulder, recalling him to the project at hand.

Kate moved things out of the way as he measured the window glass, the log wall, and his two by fours, which he took to the barn to finish. It took longer than he thought, because after a while he heard the sound of milk in a bucket. He looked over the partition to see Kate milking his cow, resting her head against the animal’s flank.

She looked so pretty, her dark hair pulled back in that jumbled, untidy way that he liked. He couldn’t help smiling when she began to hum. Ma used to do that. God knows he never hummed to a milk cow.

She finished before he did, and gratified him by coming to his impromptu workshop to perch on the grain bin and watch him groove the wood.

“I like your company,” he blurted out, then felt his face grow warm.

“I like yours, too,” she replied in her sensible way, and his embarrassment left. “You can do a little bit of anything, can’t you?”

“That’s part of running a place like this,” he said, as he blew sawdust from the frame he was building. He tossed her an extra cloth and she wiped down the wood, blowing off sawdust, too.

“There’s a dance at the Odd Fellows Hall in a couple of weeks,” he told her, after a few minutes of working up his courage. “I want to go, but I don’t know how to dance. Do you?”

“Ayuh,” she said. He grinned because she only said that now when she felt playful. “I can two-step and waltz and do something Mainers call a quadrille. I doubt you’ll need that.”

“Would you mind teaching me?”

“Not at all.” She cleared her throat. “Your father thinks you should find a wife, and it’ll never happen playing solitaire in the kitchen.”

“Not many ladies in Wyoming,” he said. Her pointed look wouldn’t allow excuses. “All right! Maybe I’ll find a wife at the dance. I’ll get married and next year you can go to the dance while we watch Pa, and find yourself a husband.” He laughed at her skeptical look. “Stranger things have happened, Katie.”

He picked up his work and she fetched the milk pail. They walked together to the house, neither in a hurry.

“Does my father talk a lot?” he asked.

“Mostly he listens as I read,” she said, and gave a satisfactory sound between a sigh and an exclamation. “We’ve come a considerable distance in the past few weeks.”

Ned helped her with the milk, even though she didn’t really need his help anymore. When he finished, he picked up the wood frame and she held up her hand to stop him.

“Ned, he wants to eat at the table and not in bed,” she said.

“The doctor said he shouldn’t exert himself,” he told her, wondering why he had to even mention the obvious.

“I know, but that’s no fun,” she replied.

“It’s not a matter of fun,” he said, maybe a little sharper than he meant to, because the subservient look came back into her eyes. He took her arm, but gently. “Katie, I want him to live longer.”

“Maybe it’s not living,” she said, her voice gentle. “He needs some say in what he wants.”

“I’m not convinced.” He released her arm. “Help me get this frame in the window?”

She nodded. He snuck another look at her, and didn’t see a woman convinced. Something told him the discussion wasn’t over, and that he might not win this one. The idea pained him less than he thought it would.

Pa insisted on watching, so they bundled him up and Ned carried him to his bedroom, over his protests that he was capable of walking. He glowered at them both, then resigned himself to sitting silent as Ned planed down the rough logs, then set in the frame for the window glass.

At his request, Kate brought in more kerosene lamps to counterbalance the full dark. The room was cold and she shivered until he went into his room, found an old sweater of his and draped it around her shoulders.

“I’ll fit in the glass now, and glaze and putty it tomorrow,” he said.

It took little time, which was good, since Pa had started to fade. He offered no objection to being carried back to Katie’s bedroom.

Ned went back to his father’s room, where Katie was wiping more sawdust off the new window ledge.

“Looks good,” she told him. “He’ll see the trees and that little rise with sagebrush.”

“Maine and Massachusetts are prettier, aren’t they?”

“Different, but maybe not prettier,” she said, and he admired her diplomacy.

“Tell me something, Katie. Would you marry a rancher around here?”

She gave it more thought than he believed the matter needed. But that was Katie. She thought things through.

“I guess not,” he said, which made her laugh, something she didn’t do too often, so it charmed him.

“I haven’t decided!” she said in humorous protest. “P’raps if I was raised here I might be tempted.”

“I mean, you were going to marry...uh...”

“Saul Coffin,” she supplied.

“And he came out here.” He stopped, noting her dismay. “I’m sorry. I shouldn’t have reminded you of Mr. Coffin.”

“That’s not it,” she said.

“What is it?” Good God, Ned thought. I am turning into a nosey person.

“I have to be honest. Some days I’m sorry he’s gone, and other days, I wonder if he is alive.”

“The sheriff in Cheyenne knows where I live, Katie. If he’s alive, we’ll hear.”

She shook out the sawdust onto the floor and started to sweep, then stopped, giving him the clear-eyed look of a realist. “I could live here in Wyoming.” She sighed. “Saul thought he could, too. You should have heard him talk about Wyoming.”

“Like it was the Garden of Eden?”

“Sort of,” she agreed. “It’s not, but I still like it.” She leaned the broom against the wall. “That’s it, Ned. You’ll meet a nice lady at the dance.”

He wondered just how much store to put into one holiday dance at the Odd Fellows Hall. “Better teach me to waltz, Katie. This could be a long ordeal.”

Chapter Twelve

Since Katie had forgotten all about purchasing material for curtains in the excitement of Pete’s job, the next day Ned had found a length of blue-and-white gingham, in a box of Ma’s old things in the barn. No one had sewn anything since Ma, so he had to help her look for the flatirons, once she had cut and hemmed and trimmed the curtains and declared they had to be ironed.

He had no trouble finding the time to help Katie search for the flatirons because she was starting to interest him. He wanted to ask her if she ever wasted a motion or even an hour, but he thought he already knew the answer.

“I vow everything is in this odd little room,” she said, as they both squeezed themselves into the storeroom off the stalls.

He heard her exclamation of delight when she found a copy of A Tale of Two Cities on a shelf with liniment bottles, a gallon or two of vinegar and unidentifiable bits and pieces of ranch life. “I wondered where that book went,” he said.

Katie’s search for flatirons stopped with the discovery of something new to read, now that she had finished Roughing It, and Pa was getting tired of her Ladies’ Home Journal stories. Hardly aware of Ned, she took the book into the kitchen and sat down at the table, where she carefully wiped away the dust. He sat down next to her with the flatirons and held them out. He clapped them together and made her laugh.

She set down the book with some reluctance, and nodded at the flatirons. In another minute, she had them warming on the stove. Back he went to the storeroom for the ironing board.

“When I iron these, we can string them on that dowel, and your Pa will have curtains,” she said. “Since I have this ironing board up, I can press a white shirt for the dance.”

“We have to go to that much trouble? I’ll be wearing a vest. Who’ll see my shirt?” he asked.

“Who will ever marry you if you don’t look presentable?” she asked. “And please tell me you have a collar and cravat somewhere.”

While she ironed, he found a pathetic collar and a cravat in even worse shape. She frowned at the collar, but she shook her head at the cravat. “I’ll make you one,” she told him.

“Out of what?”

“I have some fabric,” she said. He knew he heard something wistful in her voice, and thought perhaps he shouldn’t ask.

When she finished ironing, they each took a panel of fabric to Pa’s room and strung them on a dowel Ned had cut and sanded. Katie clapped her hands in approval and Pa smiled from his bed.

Katie had crocheted ties to hold back the fabric, giving the curtains a certain elegance he never thought to see in their jury-rigged, add-on-as-needed cabin. Ma, you would have liked this, he thought, then smiled at Katie who held her hands together in delight. You’d have liked Katie, too.

“After you find me a shirt, sit with your father,” she said.

He did as she asked, then perched on the edge of his father’s bed.