Полная версия

Stepan Bandera: The Life and Afterlife of a Ukrainian Fascist

Until now, three scholars have published monographs on the OUN. In 1955 John Armstrong published his classic and meanwhile problematic study. Roman Wysocki’s and Franziska Bruder’s monographs appeared after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, when it became possible to investigate Soviet archives. Wysocki concentrated on the OUN in Poland between 1929 and 1939. Bruder wrote a critical and thoroughly researched study of OUN ideology, paying particular attention to antisemitism and political and ethnic violence.[98] Another scholar who investigated the antisemitism of the OUN is Marco Carynnyk.[99] Alexander Motyl in 1980 and Tomasz Stryjek in 2000 presented studies on Ukrainian political thinkers, including Dmytro Dontsov, the main ideologist of the Bandera generation.[100] Grzegorz Motyka published the most comprehensive monographs on the UPA, in which he also investigated the Polish-Ukrainian conflict during the Second World War, the anti-Polish atrocities in eastern Galicia and Volhynia, and the conflict between the UPA and the Soviet authorities. Motyka’s study, however, analyzes the anti-Jewish violence only marginally.[101] Important articles on the Ukrainian police, OUN, UPA, and ethnic violence were published by Alexander Prusin.[102] Jeffrey Burds published articles on the conflict between the Ukrainian nationalists and the UPA, and on the early Cold War in Ukraine.[103] Alexander Statiev published a very well researched monograph on the conflict between the Ukrainian nationalists and the Soviet authorities, as did Karin Boeckh on Stalinism in Ukraine.[104]

An important monograph on the German occupation of eastern Ukraine (Reichskommissariat Ukraine) during the Second World War, which also pays attention to the ethnic violence of the OUN and UPA in Volhynia, was written by Karel Berkhoff.[105] Dieter Pohl published a significant and authoritative monograph on the German occupation of eastern Galicia in which he investigated in depth how the Germans, with the help of the local Ukrainian police persecuted and exterminated the Jews. The roles of the OUN, the UPA, and the local population in the Holocaust, however, are analyzed only as a sideline in this book.[106] Thomas Sandkühler, who also published a monograph on the German occupation of western Galicia, took the role of the OUN more seriously to some extent, but also concentrated on the German perpetrators.[107] Both Dieter Pohl and Frank Golczewski published several important articles on the Ukrainian police and on Ukrainian collaboration with the Germans.[108] Shmuel Spector investigated the Holocaust in Volhynia, paying special attention to survivor accounts, on the basis of which he published an important study that does not marginalize the non-German perpetrators.[109] A decade ago, Hans Heer published an article about the Lviv pogrom of 1941, and John-Paul Himka, Christoph Mick, and I did so more recently.[110] The Holocaust survivors and historians Philip Friedman and Eliyahu Yones also conducted significant studies of various aspects of the extermination of the Jews in western Ukraine, including the Lviv pogrom, and the attitude of the UPA toward the Jews.[111] The Holocaust survivor and historian Aharon Weiss published an important analytical article about Ukrainian perpetrators and rescuers.[112] In 2012 Witold Mędykowski published a transnational study of pogroms in the summer of 1941 in Belarus, the Baltic states, Poland, Romania and Ukraine.[113] Omer Bartov, Wendy Lower, Kai Struve, and Timothy Snyder have published on various issues relating to the Holocaust in western Ukraine.[114]

Several scholars published material on the subject of the Ukrainian diaspora, but with the exception of articles written by John-Paul Himka, Per Anders Rudling, and myself, the history of the OUN and Ukrainian nationalism in the Ukrainian diaspora has remained untouched.[115] Diana Dumitru, Tanja Penter, Alexander Prusin, and Vladimir Solonari published articles about the Soviet postwar investigation and trial records, and about the methodological problems related to their analysis.[116] Tarik Cyril Amar published an article about the Holocaust in Soviet discourse in western Ukraine.[117] Scholars such as Per Anders Rudling, Anton Shekhostov, and Andreas Umland published several articles about radical right groups and parties after 1990 in Ukraine.[118] Whether Ukrainian nationalism is a form of fascism has been discussed in publications by Frank Golczewski, Anton Shekhovtsov, Oleksandr Zaitsev, and myself.[119]

As already mentioned, a number of volumes of reprinted archival documents appeared in Ukraine during the last two decades.[120] They included much significant material, and should not be excluded solely because their authors, such as Volodymyr Serhiichuk, deny the ethnic and political violence of the OUN and UPA, or, like Ivan Patryliak, quote the former Ku Klux Klan Grand Wizard David Duke as an “expert” on the “Jewish Question” in the Soviet Union.[121] In addition to the above-mentioned academic studies, many books have been written by veterans of the OUN, UPA, and Waffen-SS Galizien, some of whom became professors at Western universities. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the apologetic and selective narrative initiated by these historians and other writers was taken over mostly by young Ukrainian patriotic historians and activists based in western Ukraine. On the one hand, works by Ukrainian patriotic historians such as Mykola Posivnych, and OUN veterans such as Petro Mirchuk, contain important material for a Bandera biography. On the other hand, they propagate the Bandera cult and are therefore analyzed in chapters 9 and 10, in which the Bandera cult is examined.[122]

Objectives and Limitations

This book investigates Bandera’s life and cult. It concentrates on Bandera’s political, and not his private life. It pays attention to Bandera’s thoughts and his worldview, which can be reconstructed from books and newspapers that he read, published, or edited, opinions that he held and that he expressed in public, as well as the combat and propagandist activities that he organized or participated in. The history of the OUN and UPA takes up a substantial part of the study, in order to provide important background knowledge. The form of this book is determined by the major questions, the long period covered by the narrative, and the methods applied. It thereby differs from studies that ponder the advantages and disadvantages of nationalism or socialism for the life of a nation, or that explore short-term processes such as collaboration in a particular region or country during the Second World War.

The book is written “against the grain” in order to uncover several covered-up, forgotten, ignored, or obfuscated aspects of Ukrainian and other national histories. Obviously, the study does not seek to exonerate the Germans, Soviets, Poles, or any other nation or group for the atrocities committed by them during or after the Second World War but it cannot present and does not pretend to present all relevant aspects in an entirely comprehensive way. It pays more attention to subjects such as the ethnic and political violence of the OUN and UPA than it does to German or Soviet occupation policies in Ukraine. This method of presenting history is determined by the main subject of this study, which is Bandera and his role in the Ukrainian ultranationalist movement. Parts of the book may therefore evoke the impression that the major Holocaust perpetrators in western Ukraine were the Ukrainian nationalists and not the occupying Germans and the Ukrainian police. It is not the aim of this study to argue this. This study makes clear estimates of the percentages of people who were killed by the Germans and the Ukrainian police on the one hand, and by the OUN and UPA and other Ukrainian perpetrators on the other.

It is not the aim of this book to argue that all eastern Galician and Volhynian Ukrainians (and logically not all Ukrainians) supported the politics of the OUN, fought in the UPA, were involved in the Holocaust, the ethnic cleansing against Polish population, and other forms of ethnic and political violence conducted by the OUN and UPA, or that they agreed with such actions. The study explores the interrelation between nationalism and the violence committed in its name, but it does not ignore the economic, social, and political factors that contributed to ethnic conflicts or to the formation of fascist movements.

This monograph does not negate the fact that, during the Second World War, Ukrainians were both victims and perpetrators, and that the same persons who were involved in ethnic and political violence became the victims of the Soviet regime. Moreover, the study does not suggest that all Ukrainians who were in the OUN or UPA were fascists or radical nationalists. There were different reasons for joining the OUN and UPA, and various kinds of people joined these organizations, some of them under coercion. Logically, the study does not imply that all Ukrainians who joined the OUN or UPA committed atrocities, or that among Ukrainians, only OUN and UPA members were involved in the Holocaust or other atrocities. Such an assumption would distort reality, and exonerate groups such as non-nationalist Ukrainians, the Ukrainian police, and Ukrainians who participated primarily for economic and other non-political reasons. Finally, Ukrainian political parties and organizations other than the OUN appear only marginally in this study, because the monograph concentrates on Bandera and the OUN. As a result, readers might receive the impression that the OUN was the organization that dominated the entire political life of Ukraine. This, of course, is not true. Many other nationalist, democratic, conservative, and communist organizations and parties existed in Ukraine before the Second World War, and also impacted political life there, but they are not the subject of this book.

Chapter 1:

Heterogeneity, Modernity, and the Turn to the Right

“Longue Durée” Perspective and

the Heterogeneity of Ukrainian History

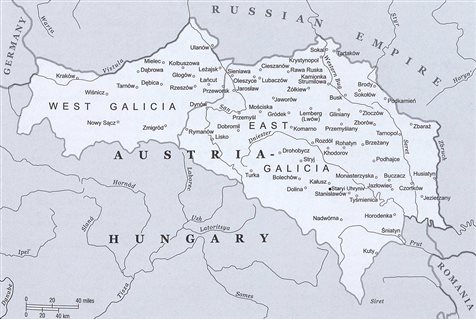

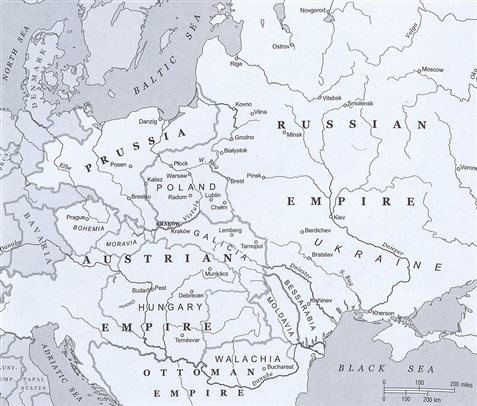

Stepan Bandera was born on 1 January 1909 in the village of Staryi Uhryniv, located in the eastern part of Galicia, the easternmost province of the Habsburg Empire. Galicia, officially known as the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria (Regnum Galiciae et Lodomeriae), was created in 1772 by the bureaucrats of the House of Habsburg at the first partition of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (Res Publica Utriusque Nationis). The province was an economically backward region with a heterogeneous population: according to statistics from 1910, 47 percent of the population were Polish, 42 percent Ukrainian, and 11 percent Jewish. The eastern part of Galicia, which the Ukrainian national movement claimed as a part of the Ukrainian nation state, and where the political cult of Stepan Bandera was born, was no less heterogeneous: 62 percent of the population were Ukrainian, 25 percent Polish, and 12 percent Jewish (Maps 1 and 2).[123]

At the time of Bandera’s birth, close to 20 percent of “Ukrainians,” or people who began to perceive themselves as Ukrainians as a result of the invention of Ukrainian national identity, lived in the Habsburg Empire (in Galicia, Bukovina and Transcarpathia). At the same time, 80 percent of Ukrainians lived in the Russian Empire (in eastern Ukraine, also known as “Russian Ukraine”).[124] This division and other political, religious, and cultural differences caused Galician Ukrainians to become a quite different people from the Ukrainians in Russian Ukraine. The division posed a difficult challenge, both for activists of the moderate, socialist-influenced, nineteenth-century national movement, such as Mykhailo Drahomanov (1841–1895), Mykhailo Hrushevs’kyi (1866–1934), and Ivan Franko (1856–1916), and later for the extreme, violent, and revolutionary twentieth-century nationalists such as Dmytro Dontsov (1883–1973), Ievhen Konovalets’ (1891–1938), and Stepan Bandera (1909–1959). These political figures tried to establish a single Ukrainian nation that would live in one Ukrainian state.[125]

To some extent, the dual and heterogeneous state of affairs was a continuation of earlier pre-modern political and cultural divisions of the territories that the Ukrainian national movement claimed as its own. In the twentieth century, the East-West division and the separate development of the two Ukrainian identities did not narrow and, due to new geopolitical circumstances, even widened. One of the most important factors that contributed to the increase of cultural and religious differences between western and eastern Ukrainians was the military conflict between the OUN-UPA and the Soviet regime during the 1940s and early 1950s. This conflict was followed by a powerful propaganda battle between nationalist factions of the Ukrainian diaspora and the Soviet Union; as a consequence, each side demonized and hated the other. In Soviet and Soviet Ukrainian discourse, the personality of Stepan Bandera acquired a significance completely different from that perceived by Galician Ukrainians. As a result, two contradictory myths relating to Stepan Bandera marked the cultural and political division of Ukraine.[126]

In nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Habsburg Galicia, the local Ukrainians identified themselves—and were identified by others—as “Ruthenians” (Ger. Ruthenen, Pol. Rusini, Ukr. Rusyny). In the Russian Empire, Ukrainians were called “Little Russians” (Rus. malorossy, Ukr. malorosy). “Ukraine” as the term for a nation only came into use in Galicia in about 1900. Although the word obviously existed long before this time, it was not the term for a nation, despite the fact that the Ukrainian national movement purported retroactively to impose such an identity on the medieval or even ancient inhabitants of “Ukrainian territories.” In the pre-modern era the term “Ukraine” referred to the “border territories” of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and Kievan Rus’. Such terms as Rosia, Russia, Rus’, Ruthenia, and Roxolonia were also used for the Ukrainian territories.[127]

In 1916 the historian Stanisław Smołka, son of the Austrian conservative and Polish nationalist politician Franciszek Smołka, to whom he dedicated his book Die Reussische Welt, argued that “the geographic Ukraine” is the “Ruthenian territory par excellence.”[128] The bureaucracy of the Russian Empire did not regard Ukrainians as a nation, but as an ethnic group with close cultural and linguistic affinities to Russians. The Ems Ukaz of 1876, which remained in force until the revolution of 1905, forbade

Map 1. Galicia 1914. YIVO Encyclopedia, 2:565.

not only printing in Ukrainian and importing literature in Ukrainian into the Russian Empire but even the use of the terms “Ukraine” and “Ukrainian.” The Ukaz caused the emigration of many Ukrainian intellectuals to Galicia, where they could publish in Ukrainian.[129]

Although the Galician Ruthenians differed from the Russian Ukrainians culturally and politically in many respects, they were similar to each other in that they lived mainly in the countryside and were under-represented in the cities and industrial regions. During the nineteenth century and the first half of the twentieth, Ukrainians in Lviv numbered between 15 and 20 percent.[130] In Kiev, 60 percent of the inhabitants spoke Ukrainian in 1864; but by 1917, only 16 percent.[131]

One group of Galician Ruthenians, known as Russophiles, further complicated the process of creating a Ukrainian nation. The origins of this movement can be traced back to the 1830s and 1840s, although it did not expand until after 1848. The Russophiles claimed to be a separate brand of Russians, although their concept of Russia was ambiguous and varied in relation to the context, between Russia as an empire, eastern Christianity, and eastern Slavs. The Russophile movement was created by Russian political activists, and by the local Ruthenian intelligentsia who were disappointed by the pro-Polish policies of the Habsburg Empire, especially in

Map 2. Eastern Europe 1815. YIVO Encyclopedia, 2:2144.

the late 1860s. The Russophiles identified themselves with Russia, partly because of the Russian belief that Ukrainian culture was a peasant culture without a tradition of statehood. Identifying with Russia, they could divest themselves of their feelings of inferiority in relation to their Polish Galician fellow-citizens who, like the Russians, possessed a “high culture” and a tradition of statehood.[132]

Galician Ukrainian culture was for centuries deeply influenced by Polish culture, while eastern Ukrainian culture was strongly influenced by Russian culture. As a result of long-standing coexistence, cultural and linguistic differences between Ukrainians and Poles on the one side became blurred, as they did between Ukrainians and Russians on the other. The differences between the western and eastern Ukrainians were evident. The Galician dialect of Ukrainian differed substantially from the Ukrainian language in Russian Ukraine. Such political, social, and cultural differences made a difficult starting point for a weak national movement that sought to establish a single nation, which was planned to be culturally different from and independent of its stronger neighbors.[133]

The western part of the Ukrainian territories was dominated by Polish culture from 1340 onwards, when King Casimir III the Great annexed Red Ruthenia (Russia Rubra), with a break between 1772 and 1867, during which Austrian politicians dominated and controlled politics in Galicia. Motivated by material and political considerations, the Ukrainian boyars and nobles had already become Catholics in pre-modern times and had adopted the Polish language. The Polonization of their upper classes left Ukrainians without an aristocratic stratum and rendered them an ethnic group with a huge proportion of peasants. Polish language and culture were associated with the governing stratum, while the Ukrainian equivalents were associated with the stratum of peasants. There were many exceptions to both propositions. For example, the Greek Catholic priests might be classified as Ukrainian intelligentsia, while there were numerous Polish peasants. However, the difference between the “dominant Poles” and the “dominated Ukrainians” caused tensions between them and, as a result of a nationalist interpretation of history, caused a strong feeling of inferiority on the part of the Ukrainians.

Until 1848, Ukrainian and Polish peasants in Galicia were serfs of their Polish landlords. They were forced to work without pay from three to six days a week on their landlords’ estates. In addition they were often humiliated and mistreated by the landowners.[134] Even when serfdom was ended in 1848, the socio-economic situation of the Galician peasants did not significantly improve for many decades. In eastern Galicia, where the majority of the peasants were Ukrainians (Ruthenians) and almost all the landlords were Poles, serfdom had a significant psychological impact on the Ukrainian national movement.[135]

The Greek Catholic Church had strongly shaped the identity of Galician Ukrainians and had influenced Galician Ukrainian nationalism from its very beginnings. The Church was originally a product of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. As the direct result of the Union of Brest of 1595‒1596, the Greek Catholic Church severed relations with the Patriarch of Constantinople and accepted the superiority of the Vatican. It did not, however, change its Orthodox or Byzantine liturgical tradition. When the Russian Empire absorbed the greatest part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth between 1772 and 1795, it dissolved the Greek Catholic Church in the incorporated territories and replaced it with the Orthodox Church. The Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church continued to function only in Habsburg Galicia, where it became a Ukrainian national church and an important component of Galician Ukrainian identity.[136]

Especially in the early stage of its existence, the Ukrainian national movement in Galicia was greatly influenced by the Greek Catholic Church. The secular intelligentsia in eastern Galicia who took part in the national movement emerged to a large extent from the families of Greek Catholic priests. Many fanatical Ukrainian activists in the nationalist cause, including Stepan Bandera himself, were the sons of priests. Furthermore, it was only with the help of the Greek Catholic priests present in every eastern Galician village that the activists of the Ukrainian national movement could reach the predominantly illiterate peasants. This situation changed only in the late nineteenth century, when such educational organizations as Prosvita established reading-rooms in villages. In these institutions the peasants could read newspapers and other publications that disseminated the idea of a secular Ukrainian nationalism.[137] However, even after a slight emancipation from the Greek Catholic Church, the Galician brand of Ukrainian nationalism was steeped in mysticism and had strong religious overtones. The Greek Catholic religion was an important symbolic foundation of the ideology of Ukrainian nationalism, although not the only one.

Modern Ukrainian nationalism, as manifested in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in Galicia, became increasingly hostile to Poles, Jews, and Russians. The hostility to Poles was related to the nationalist interpretation of their socio-economic circumstances, as well as the feeling that the Poles had occupied the Ukrainian territories and had deprived the Ukrainians of a nobility and an intelligentsia. The nationalist hostility to Jews was related to the fact that many Jews were merchants, and to the fact that some of them worked as agents of the Polish landowners. The Ukrainians felt that the Jews supported the Poles and exploited the Ukrainian peasants. The resentment toward Russians was related to the government by the Russian Empire of a huge part of the territories that the Ukrainian national movement claimed to be Ukrainian. While the Jews in Galicia were seen as agents of the Polish landowners, Jews in eastern Ukraine were frequently perceived to be agents of the Russian Empire. The stereotype of Jews supporting both Poles and Russians, and exploiting Ukrainians by means of trade or bureaucracy, became a significant image in the Ukrainian nationalist discourse.

Ukrainian nationalism thrived in eastern Galicia rather than in eastern Ukraine where the activities of the Ukrainian nationalists were suppressed by the Russian Empire. The political liberalism of the Habsburg Empire, as it developed after 1867, made Galician Ukrainians more nationalist, populist, and mystical than eastern Ukrainians. During the second half of the nineteenth century, the systematic policy of Russification in eastern Ukraine made the national distinction between Ukrainians and Russians increasingly meaningless. Most eastern Ukrainians understood Ukraine to be a region of Russia, and considered themselves to be a people akin to Russians.[138]

Because of the nationalist discourse that took place in eastern Galicia, the province was labeled as the Ukrainian “Piedmont.” Because of their loyalty to the Habsburg Empire, Galician Ukrainians were known as the “Tyroleans of the East.” In Russian Ukraine, on the other hand, the majority of the political and intellectual stratum assimilated into Russian culture and did not pay attention to Ukrainian nationalism. “Although I was born a Ukrainian, I am more Russian than anybody else,” claimed Viktor Kochubei (1768–1834), a statesman of the Russian Empire with Ukrainian origins.[139] Nikolai Gogol’ (1809–1852), born near Poltava in a family with Ukrainian traditions, described Cossack life in his novel Taras Bulba in a humorous, satirical, and grotesque way. His books appeared in elegant Russian, which included Ukrainian elements, and were written without national pathos. In 1844 Gogol’ wrote in a letter: “I myself do not know whether my soul is Ukrainian [khokhlatskaia] or Russian [russkaia]. I know only that on no account would I give priority to the Little Russian [malorosiianinu] before the Russian [russkim], or the Russian before the Little Russian.”[140]