Полная версия

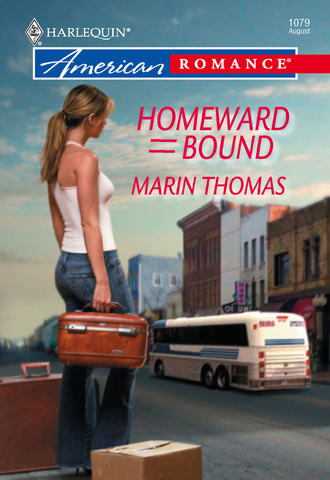

Homeward Bound

Royce stopped in the doorway and glanced around. He cleared his throat. “Do you mind?” Without waiting for an answer, he stepped farther into the room and shut the door.

She held her breath as his hand hovered over the door-knob. She didn’t know whether to be disappointed or relieved when his large masculine fingers fell away without securing the lock.

Shoving his fists into the front pockets of his jeans, he rocked back on his heels. The stubborn lug looked so out of place standing in the peach-colored room with flower-stenciled walls and a mint-green velvet canopy hanging over her bed. Barbed wire was definitely more his style.

“Your room’s nice, Heather.”

A compliment? Admiring comments from Royce had been few and far between over the years. “Anything is better than that hovel I grew up in.”

“If I’d known you cared, I’d have given you money to spruce up the trailer.”

A knot formed in her chest. She had cared. Once, she’d started to paint the kitchen a soft buttercup yellow, but her old man, in one of his drunken rages, had stumbled and fallen against the wall, smearing the paint and cursing her for ruining his clothes. After enough of those “instances,” she had realized caring was a waste of time and energy. Besides, acting as though living in a trash dump hadn’t mattered to her gave Royce one less thing to butt his nose into.

She sat on the end of her bed, smoothed a hand over the white lace spread and swallowed twice before she could trust her voice.

“Have a seat,” she said, motioning to the chair at the desk by the window.

As he crossed the room, she noticed the way his western shirt pulled at his shoulders. Noticed his backside, too. The cowboy was in a category all his own. Ranching was physical work, but most of the ranchers she’d known growing up didn’t have bodies like Royce. She’d touched a few of his impressive muscles when they’d kissed long ago, and this cowboy was in a category all his own. She wondered how he managed to stay in such great shape. She knew for a fact there wasn’t a health club within fifty miles of Nowhere.

Some fool named Sapple had opened a small sawmill in the 1920s south of town, but like so many other East Texas sawmills, the place closed up five years later. Sapple and most of the loggers and their families had moved on, but a few people stayed behind. The town was officially named Nowhere when the interstate went in twenty-five miles away, leaving the local residents out in the middle of…nowhere. Aside from a barbershop, a bank, her father’s feed store and a couple of mom-and-pop businesses, the town, surrounded by miles of ranchland and pine forests, boasted little else. If a person wanted excitement they had to get back on the interstate to find a popular restaurant or a honky-tonk.

Royce sat on her desk chair, expelled a long breath, then clasped his hands between his knees and stared at the floor.

Stomach clenching with apprehension, she asked, “What’s so important you couldn’t have told me over the phone?”

Her question brought his head up, and she stopped breathing at the solemn expression in his dark eyes. “What I have to say should be said in person.”

She almost blurted, Three years ago you had no trouble telling me that our kiss had been a terrible mistake. That you didn’t want to see me again. That you didn’t want me to come back to Nowhere. Instead, she settled for “A long time ago you had no trouble telling me over the phone to get lost.”

He stiffened, then cleared his throat and studied the Titanic movie poster hanging on the wall beside her bed. He turned his attention to her face, embarrassment and regret pinching his features. This time she looked away.

“How are you situated for money?”

The news must really be bad if Royce was stalling. “If I get the job that I applied for at the law library, I’ll be able to make ends meet this summer.” She’d already exhausted all the partial scholarships and government grants she’d been eligible for during the first four years of school. From then on, she’d had to work to pay for tuition and books, expenses and rent. She hated admitting it, hated that she was still dependent on him, but without Royce’s more-than-generous Christmas and birthday checks she would have had to drop out of college long ago.

Shifting on the chair, he removed his checkbook from the back pocket of his jeans. She had only one pen on her desk, a neon-pink one with a bright yellow feather and beaded ribbon attached to the end. She pressed her lips together to keep from smiling at the disgusted expression on his face when he tried to see around the feather as he wrote out the check.

“I don’t want your money, Royce.” Her face heated at the lie, but she felt compelled to offer a token protest.

He didn’t hand the check to her. Instead, he set the draft on top of her psychology text. “For someone who had to be forced to go to college, you’ve hung in there and beaten the odds.”

Two compliments in one day. This must be some sort of record for Royce. But knowing that she’d done something he approved of made her feel good. Proud. Vulnerable. She smiled sheepishly. “To be honest, I’m a little surprised I didn’t drop out my first year.”

“Just think. If you hadn’t been involved with that group of misfits who held up the Quick Stop, you might never have gone to college.”

Heather groaned. “Please. Let’s not bring that up.” She’d just as soon forget that fateful July night seven years ago when Royce had bailed her out of the county jail after being arrested in connection with the gas station holdup. She’d been using the restroom, unaware that the other teens had planned to rob the place. Because she hadn’t been in the store during the robbery, Royce had been able to convince the judge to let her off the hook. But the judge had added a condition of her own—college.

“The expression on your face when the judge announced your sentence was priceless. One would have thought you’d been sentenced to death, not college,” Royce chuckled, then his face sobered.

“What are your plans after you get your degree in August?”

“I want to work with children. Socioeconomically disadvantaged kids.”

He started to protest, but she held up a hand. “You’re thinking I wouldn’t be a good role model, right?” Why was it so hard for Royce to believe she’d changed since going away to school?

Shrugging, he slouched in the chair. “As long as I’ve known you, you’ve always been the one receiving help, not giving it.”

Ouch. That stung. Irritated with herself for allowing his comment to hurt, she changed the subject. “Enough reminiscing. Why the surprise visit?”

“I wish there were an easier way to say this.” He dragged a hand down his face.

The suspense rattled her nerves. “Spit it out, Royce.”

“Your father’s dead.”

She opened her mouth to suck in air, but nothing happened. Her lungs froze as her body processed the shock. After several seconds, her chest thawed, and she gulped a lungful of oxygen.

“I’m sorry, Heather.” He leaned forward again and squeezed her hand.

Numbly, she stared at the tanned hand, wondering whether the rough, calloused touch of his skin against hers or the news of her father’s death shook her more.

“How—?” Her eyes watered, surprising her. After all these years, she didn’t think she had any emotion left for her father. That she still felt something for the old man made her stomach queasy.

“A fire.”

Her gaze flew to his face. “The feed store burned down?”

He tugged his hand loose, and she bit her lip to keep from protesting the loss of his warmth and gentleness.

“The trailer caught fire. The county fire investigator believes it was accidental.”

No need to explain the gory details. As a child, how many times had she gone to bed, only to get up in the middle of the night to use the bathroom and find her father asleep on the couch, a lit cigarette dangling from between his fingers?

“A tourist passing by called 911. By the time the volunteer fire department got there…” Royce shook his head, sympathy in his eyes. “Nothing but a burned-out shell remained.”

“When?”

“Late yesterday afternoon.”

Her father was dead. She was alone in the world. Really alone. But maybe that was okay. Even when her father was alive she’d been alone. Still, Royce had always been there.

And he’s here now.

Royce stood. “I’ll wait in the truck while you pack.”

Dazed, she mumbled, “Pack?”

His eyebrows dipped. “For the funeral.”

“Funeral?” Why wasn’t anything making sense? She rubbed her temples, wincing at the onset of a headache.

He lowered his voice. “There’s usually a funeral after someone dies, Heather.”

“Why bother? No one will show up.” Not one person in Nowhere had liked her father, including her. The man had been an alcoholic, chain-smoking, card-gambling jerk.

“People will want to pay their respects to you.” He moved toward the door. “We’ll keep the service simple.”

“Simple.” She laughed at the absurdity of the whole situation. “I guess good ol’ Dad handled the cremation himself.”

Royce’s eyebrows shot straight up into his hairline. “I realize you didn’t have the best relationship with the man. But there are times when you have to do what’s right. This is one of them.”

Wondering if he could see the steam rising from the top of her head, she popped off the bed. “Ever since my mother ran off, you’ve pestered, nagged and lectured me! Well, I’ve had enough. Find yourself another hopeless cause to champion.”

His head snapped back as if she’d slapped him, then a shuttered look crept into his eyes. “Pack your bags, Heather.” His tone could have freeze-dried a whole cow. “You’re coming home.”

Home? She’d never considered the filthy, rattrap trailer she’d grown up in a home. Now, thanks to her father, there wasn’t even that.

And why would the good folks of Nowhere want to pay their respects to a girl who’d done nothing but cause them grief during her rebellious adolescent years? She wouldn’t last ten minutes in town before they ran her out. “No funeral. I’m not going back with you.”

Mr. Responsibility pinched the bridge of his nose, and guilt stabbed her. Undoubtedly, he’d already put in a hard day of ranching, then stuck his mayor cap on and solved the town’s problems, after which he’d driven three hundred miles to College Station. She didn’t doubt he’d return to the ranch tonight, wake up at dawn and start the whole boring process all over again.

“I’ll make the funeral arrangements. All you have to do is show up.”

She shook her head, hating the way her throat swelled and tears burned her eyes. Darn! She would not cry for her father. He didn’t deserve one single tear from her.

Royce’s brown eyes turned stormy. “You might consider yourself a grown-up, but when are you going to start acting like one?”

Ashamed to shove the burden of her father’s burial on Royce, she forced the words past her lips. “I’m not going back.”

The muscle along his jaw ticked. “What about the feed store?”

As far as she cared, the building could sit and rot before she’d ever set foot inside it again. “I don’t want the business. Sell it.”

“You don’t have to decide right this minute.”

“No, really. Just get rid of the place.” She lifted her chin, determined to stand her ground.

“Think about it some more. In the meantime, I’ll contact a Realtor.”

When he headed for the door, her heart skipped a beat. Part of her wanted him to leave so she could sort through the mishmash of emotions knotting her insides, yet part of her yearned for the comfort of his physical presence. Darn! She’d handled his visit badly. But for the life of her she didn’t know how to make things right.

“Royce.”

He stopped but kept his back to her.

“Thank you. For coming all this way.”

A quick nod, and then he was gone.

Just gone. She should be happy she’d escaped without having to suffer through one of his infamous hour-long sermons. Why then did she wish he’d stayed and lectured her?

Because you still haven’t gotten over him!

She flung herself across the bed and buried her face in the pillows, fighting the sting of more tears. Deep in her heart she believed she’d made the right decision not to go back with Royce. Summer classes started soon. And any day now she’d hear about the job at the law library.

Then an image of Royce’s tired face behind the steering wheel of his truck flashed through her mind. She rolled off the bed, went to her desk and lifted the check he’d left there. A thousand dollars! Her eyes zeroed in on the memo line in the bottom left-hand corner…Happy 25th birthday, Heather.

He hadn’t forgotten that tomorrow was her birthday.

She threw herself back on the bed and burst into tears.

Chapter Two

Oh, hell.

Royce hefted the last hay bale into his truck bed, then stopped to watch the cloud of dust trailing the Ford pickup that barreled toward the barn. After checking on the cattle this morning, he’d called the fire inspector and received permission to have the damaged trailer hauled to the dump. The inspector had officially closed the case, declaring Melvin Henderson’s death accidental. Royce had hoped he’d get out of here before his nosy foreman returned from an overnight visit with his ailing sister. No such luck.

Guilt nagged him at the uncharitable thought. Luke was like family. The foreman had hired on at the ranch ten years ago when Royce’s uncle had been diagnosed with cancer and been given only a few months to live. At the time Luke was fifty-five. Royce’s uncle had died in August, and the following winter his aunt had succumbed to pneumonia. After Royce had buried his aunt, he’d insisted Luke move out of the small room at the back of the barn and into the main house.

The truck came to a stop next to the corral. As soon as Luke opened the door, his old hound dog, Bandit, hopped down from the front seat. Tail wagging, the animal hurried toward Royce as fast as his arthritic legs would carry him.

Royce scratched Bandit’s ear. “How’s Martha feeling?”

“Spry as a spring chick.” Luke grumbled a four-letter word. “There wasn’t nothin’ wrong with the woman in the first place. Just lonely is all. No wonder she ain’t never married all these years. Can’t keep her trap shut for nothin’. Yakkin’ about this, yakkin’ about that. I had to get out of there before my ears shriveled up and fell off my head.”

Luke and Martha were twins, and Martha took great pleasure in bossing her brother around. Royce swallowed a laugh at the disgruntled expression on his foreman’s face, then suggested, “Why don’t you invite her to stay at the ranch for the summer. We’ve got plenty of room.”

“Hell, no! You think I want that old biddy askin’ me if I got fresh drawers on every mornin’?” Luke pulled a pouch of Skoal from the front pocket of his overalls. “How’d Heather take the news?”

“Better than I’d hoped.” He hadn’t expected her to feel much of anything at learning of her father’s death. Then he’d caught the glimmer of tears in her baby blues. The lost expression on her face had convinced him that she’d been deeply affected. He supposed no matter what kind of relationship Heather and her father had had over the years, a part of her had always yearned for his love.

“She comin’ home after graduatin’?”

“She won’t be graduating next week.” Royce slammed the tailgate shut and wiped his sweaty palms down the front of his threadbare jeans. He wasn’t in the mood to discuss Heather Henderson with anybody—not even Luke.

Last night had been hell. He’d returned from College Station right around midnight and had fallen into bed exhausted and agitated. He’d lain awake for hours, tossing and turning, his insides and outsides tied in knots.

After his accident three years ago, he’d have sworn he had put Heather behind him. Heck, he’d even had a couple of affairs. A summer fling with a tourist and an off-and-on thing with a local divorcée, whom he’d probably still be seeing if she hadn’t taken a job in Arizona.

But one glimpse at Heather—just one glimpse—and all the feelings for her that he’d thought long dead and buried had rushed to the surface, stunning him with their intensity.

After shoving a wad of chewing tobacco in his mouth, Luke offered Bandit a small pinch and the dog ran off and buried it beneath the sugar maple tree by the front porch. “How come she ain’t gettin’ her degree?”

“She still has a couple of classes to finish, first.”

“After that, is she comin’ home?”

“Nope.” Not if he had his way. Royce marched toward the barn and the old fart followed him like a pesky fly.

“Full of ‘nopes’ lately, ain’t you.”

“Yep.”

Luke stopped inside the barn doors. “You ain’t said how she was?”

“She’s fine.” Royce searched through the junk in the corner for a bushel basket. Fine didn’t come close to describing Heather. She was more than fine. She was beautiful, full of energy and life, and she possessed a new self-confidence that hadn’t been there the last time he’d seen her.

“Just fine, huh?”

“Yep.” He knew he was being an ass. But he couldn’t seem to find the words to tell Luke about Heather’s desire to work with children. About how right she’d looked sprawled on the floor buried under a pile of preschoolers. He couldn’t tell Luke that it had almost physically hurt to watch her wrestle with the kids.

Luke had been the one to find Royce lying unconscious alongside the road. Royce had awakened from surgery and the doctor had given him the bad news. In his own way, Luke had grieved along with Royce. And when the time had come to stop grieving and move on, Luke had been the one to plant his boot heel in Royce’s backside and force him out of his depression, and back into the world of the living.

Compelled to say more, Royce added, “Heather seemed excited about getting her degree at the end of the summer.”

“What kind of degree?”

“In counseling, psychology to be exact. She plans to work with disadvantaged kids.”

Bandit barked somewhere outside the barn and Luke hollered at him to hush. “What about the funeral?”

“There isn’t going to be a funeral.”

“Why not?”

“Heather doesn’t want one.”

“Can’t blame the poor gal.”

“I spoke with Pastor Gates, and he’s agreed to say a few words about Henderson during the service on Sunday.”

“Don’t deserve much more.”

No argument there. Melvin Henderson had been a first-class loser. He hadn’t had a nice word for anyone the whole time he’d been alive.

A stream of tobacco juice sailed past Royce’s face.

“How long ago did that gal start college?” asked Luke.

“Seven years.”

The geezer made a whistling sound as he sucked in air through the gap between his front teeth. “Least she didn’t up and quit on you.”

Pride surged through Royce. When Heather had chosen college over juvenile detention, he’d never expected her to last more than a semester or two. “You’re right. She might have taken her sweet time, but she didn’t quit.” He shoved aside several wooden crates, until he found a dented basket; then he carried it to the other side of the barn, where the freshly picked garden vegetables were stored.

Switching the ball of chew to his other cheek, Luke motioned to the loaded pickup. “I thought you was ridin’ fence today.”

“Change of plans. I’m meeting with a Realtor to put the feed store on the market.”

“Ain’t that Heather’s business?”

Should be. Heather might have done some growing up since going away to college, but she still ran the opposite direction when faced with the big R—responsibility. “She doesn’t want anything to do with the store.”

“Don’t seem right.”

Where Heather was concerned, nothing was ever as it seemed. If Royce were honest with himself—something he tried to avoid at all costs in order to keep his sanity—he’d admit Heather had left a void in his life when she’d gone off to college. Prior to that, his weeks had been filled with chasing after her, righting her wrongs, fixing her mistakes. When she’d graduated high school and moved to College Station his life had become…well, dull.

“It’s her decision, Luke.”

“Since when did you ever give that gal a say-so?”

“She’s had plenty of say-so’s.” Like the damn fool major she’d ended up in. Psychology. How the heck a person who’d made a mess of her own life thought she could help straighten out someone else’s baffled him.

“So you’re tyin’ up all the loose ends for her?”

“Haven’t I always kept her life tight and tidy?” Royce rubbed a hand down his face, regretting the testy remark. Heather hadn’t asked for his help; he’d offered. Now, if he could only figure out why he was so all-fired pissed off about it.

“You think she’s gonna look for a job ’round here after graduatin’?”

God, he hoped not. For the sake of his heart he prayed Heather would find a job far, far away from Nowhere. “She didn’t say.”

“What about the car?”

He glanced at the yellow Mustang sitting under a tarp at the back of the barn. His chest tightened when he thought of how he’d helped her purchase the vehicle after she’d worked her tail off to pay for the thing. He hadn’t even had to convince her to leave the Mustang behind when she left for college. She’d known the car was safer in the barn than on campus.

“Luke, I don’t have time to worry about Heather and her plans. I’ve got enough troubles with the town’s sewer system deteriorating as we speak.”

“Heard anything from the governor?”

“His aide called.” Royce carried the bushel of vegetables out of the barn, opened the tailgate and set them in the truck bed next to the hay bales. He pulled a bandana from his back pocket and mopped his brow. At ten in the morning, the temperature hovered near eighty degrees. The above-normal temperature for late May promised a long, hot Texas summer. “To a certain extent the governor is sympathetic.”

“Sympathetic how?”

“If Nowhere turns in a sizable campaign donation, the governor may be able to pull some strings and move us up on the list for government funding for a new sewer.”

“Aw, let him blow it out his ear. There ain’t enough money in this town to build a meetin’ hall, let alone throw away on a politician who don’t give a rat’s turd about our little map dot.”

“Amen. I refuse to use our five hundred and fifteen citizens’ tax dollars to finance the governor’s reelection campaign, when I can’t stand the guy in the first place.” Royce shut the tailgate.

His face puckering like a withered apple, Luke asked, “What’ll you do ’bout the sewer?”

Royce wished that every business in town had its own septic system. But during the 1940s the federal government had laid down sewer pipe as part of a work program to improve the quality of life in rural areas. As far as Royce was concerned, his town’s quality of life was disappearing faster than the water flushed down the toilets. “With a little luck, the system should hold out another year.”

He hopped into the truck, then shut the door before his foreman decided to ride along. “By next spring, I’ll figure out something.” And he would. He’d never before let down the citizens of Nowhere. One way or another he’d find the money to at least repair the sewer. He turned the key and gunned the motor. “Don’t expect me back anytime soon. After I meet with the Realtor, I plan to drop off the hay and vegetables at the Wilkinsons’ place.”

Another brown glob of tobacco flew past the truck window and landed with a splat near the front tire. “When you gonna stop givin’ everybody handouts?”

“I’m the mayor, Luke. I won’t stand by and watch four kids starve because their father’s out of work with a broken back and their mother’s run off to God-knows-where with who-knows-whom.” Right then, Heather’s mother came to mind, making Royce wonder what it was about Nowhere that had women running off in the middle of the night.