Полная версия

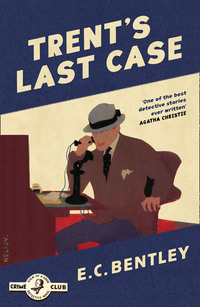

Trent Intervenes

‘No, sir; the canon had an arrangement with Mr Giles, the vicar of Cotmore, about that. The canon never knew that Mr Verey was a clergyman. He never saw him. You see, it was Mrs Verey who came to see over the place and settled everything; and it seems she never mentioned it. When we told the canon, after they had gone, he was quite took aback. “I can’t make it out at all,” he says. “Why should he conceal it?” he says. “Well, sir,” I says, “they was very nice people, anyhow, and the friends they had to see them here was very nice, and their chauffeur was a perfectly respectable man,” I says.’

Trent nodded. ‘Ah! They had friends to see them.’

The girl was thoroughly enjoying this gossip. ‘Oh yes, sir. The gentleman as brought you down, sir’—she turned to Langley—‘he brought down several others before that. They was Americans too, I think.’

‘You mean they didn’t have an English accent, I suppose,’ Langley suggested drily.

‘Yes, sir; and they had such nice manners, like yourself,’ the girl said, quite unconscious of Langley’s confusion, and of the grins covertly exchanged between Trent and the superintendent, who now took up the running.

‘This respectable chauffeur of theirs—was he a small, thin man with a long nose, partly bald, always smoking cigarettes?’

‘Oh yes, sir; just like that. You must know him.’

‘I do,’ Superintendent Owen said grimly.

‘So do I!’ Langley exclaimed. ‘He was the man we spoke to in the churchyard.’

‘Did Mr and Mrs Verey have any—er—ornaments of their own with them?’ the superintendent asked.

Ellen’s eyes rounded with enthusiasm. ‘Oh yes, sir—some lovely things they had. But they was only put out when they had friends coming. Other times they was kept somewhere in Mr Verey’s bedroom, I think. Cook and me thought perhaps they was afraid of burglars.’

The superintendent pressed a hand over his stubby moustache. ‘Yes, I expect that was it,’ he said gravely. ‘But what kind of lovely things do you mean? Silver—china—that sort of thing?’

‘No, sir; nothing ordinary, as you might say. One day they had out a beautiful goblet, like, all gold, with little figures and patterns worked on it in colours, and precious stones, blue and green and white, stuck all round it—regular dazzled me to look at, it did.’

‘The Debenham Chalice!’ exclaimed the superintendent.

‘Is it a well-known thing, then, sir?’ the girl asked.

‘No, not at all,’ Mr Owen said. ‘It is an heirloom—a private-family possession. Only we happen to have heard of it.’

‘Fancy taking such things about with them,’ Ellen remarked. ‘Then there was a big book they had out once, lying open on that table in the window. It was all done in funny gold letters on yellow paper, with lovely little pictures all round the edges, gold and silver and all colours.’

‘The Murrane Psalter!’ said Mr Owen. ‘Come, we’re getting on.’

‘And,’ the girl pursued, addressing herself to Langley, ‘there was that beautiful red coat with the arms on it, like you see on a half crown. You remember they got it out for you to look at, sir; and when I brought in the tea it was hanging up in front of the tallboy.’

Langley grimaced. ‘I believe I do remember it,’ he said, ‘now you remind me.’

‘There is the canon coming up the path now,’ Ellen said, with a glance through the window. ‘I will tell him you gentlemen are here.’

She hurried from the room, and soon there entered a tall, stooping, old man with a gentle face and the indescribable air of a scholar.

The superintendent went to meet him.

‘I am a police officer, Canon Maberley,’ he said. ‘I and my friends have called to see you in pursuit of an official inquiry in connection with the people to whom your house was let last month. I do not think I shall have to trouble you much, though, because your parlourmaid has given us already most of the information we are likely to get, I suspect.’

‘Ah! That girl,’ the canon said vaguely. ‘She has been talking to you, has she? She will go on talking for ever, if you let her. Please sit down, gentlemen. About the Vereys—ah yes! But surely there was nothing wrong about the Vereys? Mrs Verey was quite a nice, well-bred person, and they left the place in perfectly good order. They paid me in advance, too, because they live in New Zealand, as she explained, and know nobody in London. They were on a visit to England, and they wanted a temporary home in the heart of the country, because that is the real England, as she said. That was so sensible of them, I thought—instead of flying to the grime and turmoil of London, as most of our friends from overseas do. In a way, I was quite touched by it, and I was glad to let them have the vicarage.’

The superintendent shook his head. ‘People as clever as they are make things very difficult for us, sir. And the lady never mentioned that her husband was a clergyman, I understand.

‘No, and that puzzled me when I heard of it,’ the canon said. ‘But it didn’t matter, and no doubt there was a reason.’

‘The reason was, I think,’ Mr Owen said, ‘that if she had mentioned it, you might have been too much interested, and asked questions which would have been all right for a genuine parson’s wife, but which she couldn’t answer without putting her foot in it. Her husband could do a vicar well enough to pass with laymen, especially if they were not English laymen. I am sorry to say, Canon, that your tenants were impostors. Their name was certainly not Verey, to begin with. I don’t know who they are—I wish I did—they are new to us and they have invented a new method. But I can tell you what they are. They are thieves and swindlers.’

The canon fell back in his chair. ‘Thieves and swindlers!’ he gasped.

‘And very talented performers too,’ Trent assured him. ‘Why, they have had in this house of yours part of the loot of several country-house burglaries which took place last year, and which puzzled the police because it seemed impossible that some of the things taken could ever be turned into cash. One of them was a herald’s tabard, which Superintendent Owen tells me had been worn by the father of Sir Andrew Ritchie. He was Maltravers Herald in his day. It was taken when Sir Andrew’s place in Lincolnshire was broken into, and a lot of very valuable jewellery was stolen. It was dangerous to try to sell the tabard in the open market, and it was worth little, anyhow, apart from any associations it might have. What they did was to fake up a story about the tabard which might appeal to an American purchaser, and, having found a victim, to induce him to buy it. I believe he parted with quite a large sum.’

‘The poor simp!’ growled Langley.

Canon Maberley held up a shaking hand. ‘I fear I do not understand,’ he said. ‘What had their taking my house to do with all this?’

‘It was a vital part of the plan. We know exactly how they went to work about the tabard; and no doubt the other things were got rid of in very much the same way. There were four of them in the gang. Besides your tenants, there was an agreeable and cultured person—I should think a man with real knowledge of antiquities and objects of art—whose job was to make the acquaintance of wealthy people visiting London, gain their confidence, take them about to places of interest, exchange hospitality with them, and finally get them down to this vicarage. In this case it was made to appear as if the proposal to look over your church came from the visitors themselves. They could not suspect anything. They were attracted by the romantic name of the place on a signpost up there at the corner of the main road.’

The canon shook his head helplessly. ‘But there is no signpost at that corner.’

‘No, but there was one at the time when they were due to be passing that corner in the confederate’s car. It was a false signpost, you see, with a false name on it—so that if anything went wrong, the place where the swindle was worked would be difficult to trace. Then, when they entered the churchyard their attention was attracted by a certain gravestone with an inscription that interested them. I won’t waste your time by giving the whole story—the point is that the gravestone, or rather the top layer which had been fitted onto it, was false too. The sham inscription on it was meant to lead up to the swindle, and so it did.’

The canon drew himself up in his chair. ‘It was an abominable act of sacrilege!’ he exclaimed. ‘The man calling himself Verey—’

‘I don’t think,’ Trent said, ‘it was the man calling himself Verey who actually did the abominable act. We believe it was the fourth member of the gang, who masqueraded as the Vereys’ chauffeur—a very interesting character. Superintendent Owen can tell you about him.’

Mr Owen twisted his moustache thoughtfully. ‘Yes; he is the only one of them that we can place. Alfred Coveney, his name is; a man of some education and any amount of talent. He used to be a stage-carpenter and property-maker—a regular artist, he was. Give him a tub of papier-mâché, and there was nothing he couldn’t model and colour to look exactly like the real thing. That was how the false top to the gravestone was made, I’ve no doubt. It may have been made to fit on like a lid, to be slipped on and off as required. The inscription was a bit above Alf, though—I expect it was Gifford who drafted that for him, and he copied the lettering from other old stones in the churchyard. Of course the fake sign-post was Alf’s work too—stuck up when required, and taken down when the show was over.

‘Well, Alf got into bad company. They found how clever he was with his hands, and he became an expert burglar. He has served two terms of imprisonment. He is one of a few who have always been under suspicion for the job at Sir Andrew Ritchie’s place, and the other two when the Chalice was lifted from Eynsham Park and the Psalter from Lord Swanbourne’s house. With what they collected in this house and the jewellery that was taken in all three burglaries, they must have done very well indeed for themselves; and by this time they are going to be hard to catch.’

Canon Maberley, who had now recovered himself somewhat, looked at the others with the beginnings of a smile. ‘It is a new experience for me,’ he said, ‘to be made use of by a gang of criminals. But it is highly interesting. I suppose that when these confiding strangers had been got down here, my tenant appeared in the character of the parson, and invited them into the house, where you tell me they were induced to make a purchase of stolen property. I do not see, I must confess, how anything could have been better designed to prevent any possibility of suspicion arising. The vicar of a parish, at home in his own vicarage! Who could imagine anything being wrong? I only hope, for the credit of my cloth, that the deception was well carried out.’

‘As far as I know,’ Trent said, ‘he made only one mistake. It was a small one; but the moment I heard of it I knew that he must have been a fraud. You see, he was asked about the oar you have hanging up in the hall. I didn’t go to Oxford myself, but I believe when a man is given his oar it means that he rowed in an eight that did something unusually good.’

A light came into the canon’s spectacled eyes. ‘In the year I got my colours the Wadham boat went up five places on the river. It was the happiest week of my life.’

‘Yet you had other triumphs,’ Trent suggested. ‘For instance, didn’t you get a Fellowship at All Souls, after leaving Wadham?’

‘Yes, and that did please me, naturally,’ the canon said. ‘But that is a different sort of happiness, my dear sir, and, believe me, nothing like so keen. And by the way, how did you know about that?’

‘I thought it might be so, because of the little mistake your tenant made. When he was asked about the oar, he said he had rowed for All Souls.’

Canon Maberley burst out laughing, while Langley and the superintendent stared at him blankly.

‘I think I see what happened,’ he said. ‘The rascal must have been browsing about in my library, in search of ideas for the part he was to play. I was a resident Fellow for five years, and a number of my books have a bookplate with my name and the name and arms of All Souls. His mistake was natural.’ And again the old gentleman laughed delightedly.

Langley exploded. ‘I like a joke myself,’ he said, ‘but I’ll be skinned alive if I can see the point of this one.’

‘Why, the point is,’ Trent told him, ‘that nobody ever rowed for All Souls. There never were more than four undergraduates there at one time, all the other members being Fellows.’

II

THE SWEET SHOT

‘NO; I happened to be abroad at the time,’ Philip Trent said. ‘I wasn’t in the way of seeing the English papers, so until I came here this week I never heard anything about your mystery.’

Captain Royden, a small, spare, brown-faced man, was engaged in the delicate—and forbidden—task of taking his automatic telephone instrument to pieces. He now suspended his labours and reached for the tobacco-jar. The large window of his office in the Kempshill clubhouse looked down upon the eighteenth green of that delectable golf course, and his eye roved over the whin-clad slopes beyond as he called on his recollection.

‘Well, if you call it a mystery,’ he said as he filled a pipe. ‘Some people do, because they like mysteries, I suppose. For instance, Colin Hunt, the man you’re staying with, calls it that. Others won’t have it, and say there was a perfectly natural explanation. I could tell you as much as anybody could about it, I dare say.’

‘As being secretary here, you mean?’

‘Not only that. I was one of the two people who were in at the death, so to speak—or next door to it,’ Captain Royden said. He limped to the mantelshelf and took down a silver box embossed on the lid with the crest and mottoes of the Corps of Royal Engineers. ‘Try one of these cigarettes, Mr Trent. If you’d like to hear the yarn, I’ll give it you. You have heard something about Arthur Freer, I suppose?’

‘Hardly anything,’ Trent said. ‘I just gathered that he wasn’t a very popular character.’

‘No,’ Captain Royden said with reserve. ‘Did they tell you he was my brother-in-law? No? Well, now, it happened about four months ago, on a Monday—let me see—yes, the second Monday in May. Freer had a habit of playing nine holes before breakfast. Barring Sundays—he was strict about Sunday—he did it most days, even in the beastliest weather, going round all alone usually, carrying his own clubs, studying every shot as if his life depended on it. That helped to make him the very good player he was. His handicap here was two, and at Undershaw he used to be scratch, I believe.

‘At a quarter to eight he’d be on the first tee, and by nine he’d be back at his house—it’s only a few minutes from here. That Monday morning he started off as usual—’

‘And at the usual time?’

‘Just about. He had spent a few minutes in the clubhouse blowing up the steward about some trifle. And that was the last time he was seen alive by anybody—near enough to speak to, that is. No one else went off the first tee until a little after nine, when I started round with Browson—he’s our local padre; I had been having breakfast with him at the vicarage. He’s got a game leg, like me, so we often play together when he can fit it in.

‘We had holed out on the first green, and were walking onto the next tee, when Browson said: “Great Scot! Look there. Something’s happened.” He pointed down the fairway of the second hole; and there we could see a man lying sprawled on the turf, face-down and motionless. Now there is this point about the second hole—the first half of it is in a dip in the land, just deep enough to be out of sight from any other point on the course, unless you’re standing right above it—you’ll see when you go round yourself. Well, on the tee, you are right above it; and we saw this man lying. We ran to the spot.

‘It was Freer, as I had known it must be at that hour. He was dead, lying in a disjointed sort of way no live man could have lain in. His clothing was torn to ribbons, and it was singed, too. So was his hair—he used to play bareheaded—and his face and hands. His bag of clubs was lying a few yards away, and the brassie, which he had just been using, was close by the body.

‘There wasn’t any wound showing, and I had seen far worse things often enough, but the padre was looking sickish, so I asked him to go back to the clubhouse and send for a doctor and the police while I mounted guard. They weren’t long coming, and after they had done their job the body was taken away in an ambulance. Well, that’s about all I can tell you at first hand, Mr Trent. If you are staying with Hunt, you’ll have heard about the inquest and all that, probably.’

Trent shook his head. ‘No,’ he said. ‘Colin was just beginning to tell me, after breakfast this morning, about Freer having been killed on the course in some incomprehensible way, when a man came to see him about something. So, as I was going to apply for a fortnight’s run of the course, I thought I would ask you about the affair.’

‘All right,’ Captain Royden said. ‘I can tell you about the inquest anyhow—had to be there to speak my own little piece, about finding the body. As for what had happened to Freer, the medical evidence was rather confusing. It was agreed that he had been killed by some tremendous shock, which had jolted his whole system to pieces and dislocated several joints, but had been not quite violent enough to cause any visible wound. Apart from that, there was a disagreement. Freer’s own doctor, who saw the body first, declared he must have been struck by lightning. He said it was true there hadn’t been a thunderstorm, but that there had been thunder about all that weekend, and that sometimes lightning did act in that way. But the police surgeon, Collins, said there would be no such displacement of the organs from a lightning stroke, even if it did ever happen that way in our climate, which he doubted. And he said that if it had been lightning, it would have struck the steel-headed clubs; but the clubs lay there in their bag quite undamaged. Collins thought there must have been some kind of explosion, though he couldn’t suggest what kind.’

Trent shook his head. ‘I don’t suppose that impressed the court,’ he said. ‘All the same, it may have been all the honest opinion he could give.’ He smoked in silence a few moments, while Captain Royden attended to the troubles of his telephone instrument with a camel-hair brush. ‘But surely,’ Trent said at length, ‘if there had been such an explosion as that, somebody would have heard the sound of it.’

‘Lots of people would have heard it,’ Captain Royden answered. ‘But there you are, you see—nobody notices the sound of explosions just about here. There’s the quarry on the other side of the road there, and any time after seven a.m. there’s liable to be a noise of blasting.’

‘A dull, sickening thud?’

‘Jolly sickening,’ Captain Royden said, ‘for all of us living near by. And so that point wasn’t raised. Well, Collins is a very sound man; but as you say, his evidence didn’t really explain the thing, and the other fellow’s did, whether it was right or wrong. Besides, the coroner and the jury had heard about a bolt from a clear sky, and the notion appealed to them. Anyhow, they brought it in death from misadventure.’

‘Which nobody could deny, as the song says,’ Trent remarked. ‘And was there no other evidence?’

‘Yes, some. But Hunt can tell you about it as well as I can; he was there. I shall have to ask you to excuse me now,’ Captain Royden said. ‘I have an appointment in the town. The steward will sign you on for a fortnight, and probably get you a game too, if you want one today.’

Colin Hunt and his wife, when Trent returned to their house for luncheon, were very willing to complete the tale. The verdict, they declared, was tripe. Dr Collins knew his job, whereas Dr Hoyle was an old footler, and Freer’s death had never been reasonably explained.

As for the other evidence, it had, they agreed, been interesting, though it didn’t help at all. Freer had been seen after he had played his tee-shot at the second hole, when he was walking down to the bottom of the dip towards the spot where he met his death.

‘But according to Royden,’ Trent said, ‘that was a place where he couldn’t be seen, unless one was right above him.’

‘Well, this witness was right above him,’ Hunt rejoined. ‘Over one thousand feet above him, so he said. He was an R.A.F. man, piloting a bomber from Bexford Camp, not far from here. He was up doing some sort of exercise, and passed over the course just at that time. He didn’t know Freer, but he spotted a man walking down from the second tee, because he was the only living soul visible on the course. Gossett, the other man in the plane, is a temporary member here, and he did know Freer quite well—or as well as anybody cared to know him—but he never saw him. However, the pilot was quite clear that he saw a man just at the time in question, and they took his evidence so as to prove that Freer was absolutely alone just before his death. The only other person who saw Freer was another man who knew him well; used to be a caddy here, and then got a job at the quarry. He was at work on the hillside, and he watched Freer play the first hole and go on to the second—nobody with him, of course.’

‘Well, that was pretty well established then,’ Trent remarked. ‘He was about as alone as he could be, it seems. Yet something happened somehow.’

Mrs Hunt sniffed sceptically, and lighted a cigarette. ‘Yes, it did,’ she said. ‘However, I didn’t worry much about it, for one. Edith—Mrs Freer, that is: Royden’s sister—must have had a terrible life of it with a man like that. Not that she ever said anything—she wouldn’t. She is not that sort.’

‘She is a jolly good sort, anyhow,’ Hunt declared.

‘Yes, she is; too good for most men. I can tell you,’ Mrs Hunt added for the benefit of Trent, ‘if Colin ever took to cursing me and knocking me about, my well-known loyalty wouldn’t stand the strain for very long.’

‘That’s why I don’t do it. It’s the fear of exposure that makes me the perfect husband, Phil. She would tie a can to me before I knew what was happening. As for Edith, it’s true she never said anything, but the change in her since it happened tells the story well enough. Since she’s been living with her brother she has been looking far better and happier than she ever succeeded in doing while Freer was alive.’

‘She won’t be living with him for very long, I dare say,’ Mrs Hunt intimated darkly.

‘No. I’d marry her myself if I had the chance,’ Hunt agreed cordially.

‘Pooh! You wouldn’t be in the first six,’ his wife said. ‘It will be Rennie, or Gossett, or possibly Sandy Butler—you’ll see. But perhaps you’ve had enough of the local tittle-tattle, Phil. Did you fix up a game for this afternoon?’

‘Yes; with the Jarman Professor of Chemistry in the University of Cambridge,’ Trent said. ‘He looked at me as if he thought a bath of vitriol would do me good, but he agreed to play me.’

‘You’ve got a tough job,’ Hunt observed. ‘I believe he is almost as old as he looks, but he is a devil at the short game, and he knows the course blindfolded, which you don’t. And he isn’t so cantankerous as he pretends to be. By the way, he was the man who saw the finish of the last shot Freer ever played—a sweet shot if ever there was one. Get him to tell you.’

‘I shall try to,’ Trent said. ‘The steward told me about that, and that was why I asked the professor for a game.’

Colin Hunt’s prediction was fulfilled that afternoon. Professor Hyde, receiving five strokes, was one up at the seventeenth, and at the last hole sent down a four-foot putt to win the match. As they left the green he remarked, as if in answer to something Trent had that moment said: ‘Yes; I can tell you a curious circumstance about Freer’s death.’

Trent’s eye brightened, for the professor had not said a dozen words during their game, and Trent’s tentative allusion to the subject after the second hole had been met merely by an intimidating grunt.

‘I saw the finish of the last shot he played,’ the old gentleman went on, ‘without seeing the man himself at all. A lovely brassie it was, too—though lucky. Rolled to within two feet of the pin.’