Полная версия

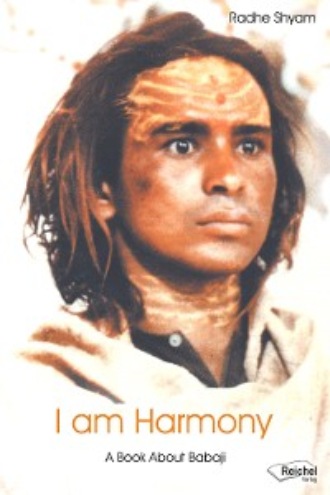

I am Harmony

In His teaching and life, Babaji used miraculous powers, but indicated (as have other Masters} that they are attainable by anyone who can exercise the discipline to focus his or her mind and follow their Path to unity with The Divine. The powers come from thinking, working, living in harmony with the Creative Energy of the Universe. Babaji, for example, knew - even before they arrived or spoke to Him - who was coming to His ashram, whether they were ready for the experience of Haidakhan, whether they should stay or go. He read people's minds, healed their ailments, guided them into experiences they needed. And it has been people's experience that He comes and goes in human form, at will, through the course of human history.

His Message is not sectarian, but for all human beings of whatever religious or philosophical leaning. Hindus, Moslems, Christians, Parsis, agnostics, animists, atheists, and others came to live and learn in His presence. His teachings and actions express the best in all religions and can challenge, enrich and expand spiritual knowledge, wisdom and experience within the framework of any of them. Krishna, Moses, Jesus, Mohammed, all stated that their highest and best followers can be identified by how they live - how they put into practice the religion they profess. Jesus, when asked "Which is the first commandment of all?", answered, "...thou shalt love the Lord thy God with all thy heart, and with all thy soul, and with all thy mind, and with all thy strength: this is the first commandment. And the second is like, namely this, Thou shalt love thy neighbour as thyself." Babaji s teachings are focused on living in harmony with The Divine, and loving the whole of Creation as thyself, more than on worshiping The Divine by any particular ritual or belief. He would surely agree with a statement attributed to His old friend, Neemkaroli Baba, "It is better to see God in everything than to try to figure it out."

When He had given His message, through example, experience and teaching, Babaji left, in order that people might absorb the Message and learn to live in Truth, Simplicity and Love, rather than to blindly follow His charming and beautiful Presence like so many sheep.

This book is a collection of people's experiences of Babaji; it is something of a biography of Babaji based on personal stories and recollections of people in whose veracity I have reason to believe. No one person and no one book can possibly "capture" this Being in print: The Divine in Its manifest forms is beyond human capacity to understand or to relate. Still, I invite you to read this book about Babaji as I and others have experienced Him. He does not come to create a new religion or to establish a "new God"; He comes to remind and teach humankind of a harmonious way of life. Whether you experience Babaji as divine or as a stimulating, challenging, unusual human being, His life and message (which are really the same thing) have much to offer to people in this era of change and possible growth.

"I surrender to Thee, O Lord; Thou alone art my refuge; Thou alone art my mother, my father, my kin, my all; Thou art my Lord in the world and in the scriptures. Hail, hail, O King of Sages, Remover of the pain of Thy devotees! From the Haidakhan Aarati (worship service)

CHAPTER I

WE MEET HAIDAKHAN BABA

Margaret met me in New Delhi on February 21, 1980, and insisted we go the very next morning to meet Babaji, despite an unconfirmed business meeting I had requested at the Indian Ministry of External Affairs. We arranged for a car and driver and rode for two and a half hours south, to Vrindaban, where there is a Babaji ashram.

We rode across the flat plains of central India, sharing the sometimes divided highway with forms of transportation that reflected thousands of years of human existence - cars, smoke-belching trucks, crowded buses, two-wheeled, horse-drawn carts, four-wheeled, rubber-tired ox carts, a few camels, one or two laden elephants, and hundreds of people walking along the side, carrying everything from children to bundles of firewood and jugs of water. It was a lovely scene (and a slow ride), similar to what I had experienced in other third-world countries during my just-completed career in the Department of State in Washington, D.C.

What was more unusual, in my experience, was the peaceful repose of a sari-clad Margaret sitting beside me as we drove to meet Babaji. In the United States, Margaret Gold was a lawyer and teacher of law, a dynamo of energy directed at relieving the problems of all who came into her sphere. For much of the time as we drove, she was content to sit quietly, repeating a mantra6 as she moved the beads of her mala (rosary) through her fingers, and occasionally pointing out to me the timeless beauties of the Indian landscape. It was clear that the seven weeks she had spent in Babaji's presence in India had made a profound change in Margaret.

When we reached Vrindaban, our driver slowly and carefully threaded his way through the crowded, narrow streets of the ancient town, famed as the childhood home of the great Lord Krishna. The rivers of people, rickshaws, hand carts, ox carts, cows, pigs and other cars parted gently to allow our progress to the winding, narrow lane on which Babaji's Vrindaban ashram is located. Our driver parked in a wide spot in the street and Margaret led me toward the door of the ashram.

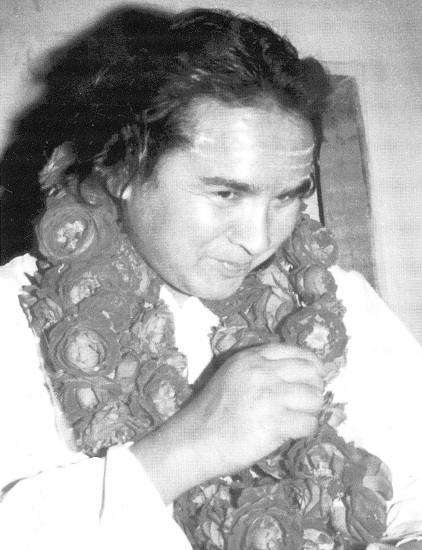

We left our shoes on a porch outside the entrance, along with a hundred other pairs of shoes and sandals, and walked into Babaji s ashram. The temple, which occupies two-thirds of the ground floor area of the ashram, was jammed with perhaps four hundred devotees who were sitting cross-legged on the floor, singing and chanting rhythmically, with harmonium, drums and bells playing. Margaret and I got into the long line of people who were going to where Babaji sat, yogi-fashion, on a raised dais, blessing devotees, receiving their gifts of flower garlands, candies, nuts, fruits, etc., and Himself giving out gifts. Margaret and I both had gifts for Babaji. Margaret had a mobile of hearts from Finland and I had a golden, heart-shaped locket that I had bought in Paris for $300 and on which I had paid another $100 in customs duties at the airport in Bombay.

It took perhaps fifteen minutes for us to reach Babaji, so I had a chance to see how people knelt before Him and touched His feet, handed Him a gift, or just raised up for His touch of blessing. When my turn came, I felt awkward in kneeling and touching my forehead to the floor before Him, but I did that and looked up at Him. Babaji was older - looking like someone in his early 30's - and chubbier than the photographs of Him that I had seen. He looked intently into my eyes as I reached to hand Him my little jewel box with its locket and chain. Babaji took the box, gave it a puzzled look and handed it back to me to open. I opened the box and gave it back to Babaji, who glanced casually at my gift - apparently far less impressed by it than I - and gave it to the devotee standing at His left who was handling the gifts which Babaji did not immediately give away.

I stood up to go, but Babaji motioned for me to sit down before Him at His right. So I sat on the floor, legs crossed, and watched Babaji for five or ten minutes. He sat soberly, with His hand raised in blessing, for some devotees. Others He received with a smile or laughter and a touch of blessing, perhaps exchanging a few words in Hindi. With an impish grin on His face, He threw apples, oranges, and candies into the laps of the ladies and children sitting directly in front of Him. There was constant hustle, noise, and activity swirling around Babaji, and yet an atmosphere of peace and serenity. I remembered the many "little miracles" of my European trip on my way to India and I chuckled to myself as I inwardly asked, "Is this God on earth?"

After a few minutes, the mustachioed Indian devotee standing at Shri Babaji's left came to me and said Babaji had told him to take me to see "Swamiji," who could answer my questions in English. I wondered if Babaji had been reading my mind, as people said He did. We picked our way through the crowded temple to the far corner where Swami Fakiranand7, a 70-year-old devotee who administered Babaji's ashram at Haidakhan, sat selling English and Hindi literature about Babaji. We talked for a few minutes about Babaji as the present physical manifestation of the scriptural Lord Shiva; then Swamiji was called away to a meeting. I stood up in that corner farthest from Babaji and watched the scene, so foreign to anything that even my Foreign Service travels had prepared me for.

Soon I saw Babaji beckoning for someone to come to Him. The man next to me said Babaji was telling me to come, so I walked back through the crowd, feeling that four hundred pairs of eyes were on me. As I knelt before Babaji, He opened a cardboard box and took out two big round pieces of sugar-and-milk candy and placed them in my right hand. I sat at His feet, eating the candy and looking up into His face. He was full of kindness and love, beyond anything I recollect having seen in any person's face and form; He seemed to literally radiate that love, like a measurable energy force. Suddenly, Babaji moved to get up; He leaned forward, put both His hands on my back and raised Himself to His feet, then hurried along the path through the crowd and out of the temple area. It was time for lunch. Margaret and her American and European friends came to tell me that Babaji had honored me greatly in His welcome and that I had been greatly blessed. I had no experience of how Babaji greeted other newcomers, but my mind and body held the 'charge' of His blessing for a long time. Even through the great confusion of entering into a culture that was very strange to me, I felt that I had been pulled to Babaji by His will and in His time.

In typical ashram fashion, we sat cross-legged on the floor of the temple for our noon meal, about a hundred people at each sitting. Plates made of broad leaves sewn together were placed before each person and devotees served us, from steaming buckets, with rice, lentils, vegetables, fried bread (chapatis), a sweet, and tea in stainless steel 'glasses.' The food we ate had been offered first to Babaji and blessed by Him. This blessed food is called prasad: all the meals served to Babaji's devotees, wherever He went, were blessed and served as prasad. We ate with our right hands. As I ate, Shri Babaji came back into the temple, stood before me, and asked my name.

After prasad, there was a period for rest and household activities before Babaji's late afternoon darshan - the time in which a saint sits with devotees to share his or her radiance, advice and uplifting energy - and the evening aarati (a sung worship service). Margaret and I went to a guesthouse and napped and bathed before starting back to Babaji's ashram.

Vrindaban is the town where Lord Krishna, a great manifestation of The Divine as Lord Vishnu, and the central character of the Indian epic, The Mahabharata, lived as a child with his cow-herding tribe. Scriptural tradition places Lord Krishna's time in Vrindaban about 6700 years ago, but many historians guess the time to be much closer to the birth of Christ. Recent archaeological finds push the date back toward the traditional dates. Under any circumstances, Vrindaban is an old town and its narrow, winding, crowded streets, even though paved now with asphalt, provide the many religious pilgrims and tourists with a setting more conducive to spiritual search than the bustling, aggressive commercial cities of India. Vrindaban is still famous for its milk and milk products and there are many street-side stalls and shops where delicious hot milk or milky tea, called chai, is served, and we could buy milk-and-sugar sweets to offer to Shri Babaji. Outside the many temples, street vendors offered flower garlands at a rupee or so each, to be offered to The Divine during the evening worship services. The streets were full of activity - shoppers, vendors, strollers, rickshaws, bicycles, horse-drawn carts, ox carts, a few cars, many cows, some pigs and piglets. As the afternoon came to a close, Vrindaban's thousand temples offered up the sounds of bells and gongs and chanting and the sweet scent of incense.

Babaji's ashram also filled and again people waited in long lines to touch His feet with reverence and offer their gifts and themselves, while Om Namah Shivaya8 was sung to many tunes. That evening, after aarati, when I placed a flower garland on Babaji's knees and knelt before Him, He put the garland around my neck. On my way back to my place, I stopped in a darkened area behind and to the left of Babaji to talk with an Indian devotee. I happened to look away from the devotee to look at Babaji: I saw He had turned just at that second to look over His left shoulder at me, and before I could even smile at Him, I was aware of an orange flying past a column and over the outstretched hands of three or four devotees - a left-handed, sideways shot that hit me square in the chest, as if to say, "Who else but God could make a shot like that?" Babaji laughed and turned back to the devotees in front of Him.

For two days Margaret and I were caught up in the excitement and joy of being with Babaji. We were up at 3:30 a.m. to bathe and make our way to the temple before 5 for the first activity of the day. Hours were spent in the temple, singing and chanting and being bathed in the waves of love, peace and joy emanating from Babaji and His devotees. We talked with devotees from many parts of India, Europe and North America, hearing tales of their experiences with Babaji.

After two days, Margaret and I went back to Delhi to tend to my business with the Ministry of External Affairs; then we drove back to Vrindaban. We arrived at the temple late in the evening; the service was over, the temple nearly empty and scantily lit. We feared we had missed Babaji, who was about to leave for Bombay. But Babaji appeared out of the dark shadows in the temple and, through interpreters, told Margaret and me to join Swamiji and a party of mostly Western devotees who were going to the ashram in Haidakhan that night.

We rode through the night on the narrow-gauge train to Haldwani, at the edge of the plains where the foothills of the Himalayas begin to rise. Pedal rickshaws carried us, two by two, with baggage behind, through busy shopping streets to the modest shop of Trilok Singh, a grain and vegetable dealer and strong devotee of Babaji, from which place most of the last 'legs' of people's trips to Haidakhan depart. On this occasion, there was a jeep to take Swamiji and some of his party to the end of the road up the river valley, to what is known as "the dam site."

As the jeep wound its way through the hills overlooking the river, I was amazed at the beauty of the area. Most of the hills are covered with trees - lots of pine - and, here and there, families had cleared, over the years, terraces along the hillside which were, at that season, richly green with corn, wheat, or vegetables. On the edges of some of the fields were stone houses with red tin roofs and barns, outside of which oxen and buffaloes stood or lay. Overhead, eagles flew; a family of monkeys fled through the trees as the jeep rolled by. Down in the wide, stony valley a chastened river flowed quietly in one or more channels down a largely dry bed; the river's time to howl is from July through September, when the monsoon turns the quiet stream into a raging demon and cuts off easy access between the Haidakhan valley and the plains.

In the mid-70's, the Indian Government decided to build a dam near the mouth of 'Babaji's' Gautam Ganga (the river which flows through Babaji's ashram at Haidakhan) in order to supply water to plains cities and farms. A road was built to the dam site, which greatly benefited the farmers of the valley. But despite work crews at the site every year and a dedication speech by Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, the dam has never gotten under way. Nor is it likely to, since engineers note that the rock at the site is too crumbly, too likely to shift, to support a dam; and the monsoon erosion would fill the reservoir with mud within ten or fifteen years, anyway. But the project has supplied needed jobs in the valley, brought buses to the mouth of the valley, and created tea shops where travelers to and from Haidakhan and other villages can sit while they wait for the infrequent buses.

Our jeep stopped at the dam site and we got out to walk the remaining three or four miles up the riverbed to Haidakhan. Village men carried our baggage for ten rupees (about one dollar) - a price then set and enforced by Babaji to provide villagers with a fair income and to keep villagers from gouging naive foreigners who would pay almost anything asked. On our hike up the river on that trip, I counted twenty-one river crossings, some ankle-deep, some knee-deep. As our party walked, we met valley dwellers going to the bus, dogs barked at us from their hillside stations, and as we neared the houses on the hillsides, children came out to shout "Bhole Baba ki jai!" - "Hail to the Simple Father!" - one of Shri Babaji's many names. There was a strong sense of coming home, despite the strangeness of the whole scene and culture.

Within sight of the ashram, about a quarter mile downstream, there is an island in the riverbed on which a tree grows. Legend has it that Lord Shiva brought His consort to the mount known locally as Mount Kailash, which rises above the island, and that Sati used to bathe in the river by the island. The crown of this Mount Kailash and the cave at its feet are associated with Lord Shiva's doing thousands of years of tapas (meditation and other spiritual practices) here for the benefit of humankind. There is now an orange-painted statue of Shri Hanuman - a god9 with the form of a monkey, who came to earth to serve Lord Ram and His consort, Sita - stationed on this island to greet and bless travelers and pilgrims.

I was confused by the numbers of gods and holy figures I was being 'introduced to' in the Hindu culture and I asked what to make of Hanuman. I learned then (and over and over in later experience) that despite the hundreds of identifiable, storied gods, goddesses, and demons in the Hindu culture and religion, the scriptures and thoughtful Hindus firmly declare that "The Lord is One, without a second."10 The multiplicity of gods and goddesses arises from human efforts to demonstrate and give form to the many aspects of the One, Formless God, to illustrate and personalize the laws which make the universe operate in harmony and the principles which underlie the creation, maintenance and 'destruction' (or purification) of the universe. Adherents worship that form - or those forms - of The Divine which are most attractive to them, or whose qualities they wish to attain. And, if one gives credence to statements from past and present, The Divine appears to sincere devotees in the forms that they worship and expect to encounter. Hanuman, noted for his strength and his wholehearted devotion and service to God (as Lord Ram), is a great favorite all over India. Hanuman is also a great favorite of Shri Babaji and His devotees.

Our journey up the valley ended with a climb up what is called "The 108 Steps." (There are actually a few more than 108 steps from the riverbed to the ashram's temple garden, but 108 has a spiritual and numerological significance.) Near the top of the steps is a one-story building housing an office and tiny bedroom for Swami Fakiranand, facing the steps, and, facing the other direction, a small room in which Babaji slept and received visitors. Outside Babaji's room was a concrete terrace which contained an ancient pipal tree and a sacred fire pit, at which Babaji performed a dawn fire ceremony every day He was in Haidakhan. The terrace, shaded by the sacred pipal tree, looks out over the valley and the little village of Haidakhan. Margaret and I spent ten days in the Haidakhan ashram, living very simply and following the schedule which Babaji had established. We got up at 4 a.m. and went to the river to bathe, in predawn temperatures hovering around 40 degrees Fahrenheit. There was an hour or so for meditation and a hot cup of chai before the hour-long aarati service at sun-up. The ashram did not serve breakfast. The concept was that one meal a day, at noon, is sufficient for simple living, but Babaji also provided an evening supper and frequently distributed fruits, nuts and candies, or gave tea parties, so no one felt hunger. But Western devotees, used to breakfast, found cereals and buffalo milk or cheese and biscuits and chai at the village tea shops. Then we went to work.

Shri Babaji taught that work done without selfish, personal motive, dedicated to The Divine as service performed in harmony with all of Creation, is the highest form of worship. It is also a means of purification for a devotee, transforming inner negativity and hostility and opening the individual to spiritual growth. This is karma yoga. So there were work sessions both morning and afternoon. Our work at that time was enlarging the terrace on the right bank of the Gautam Ganga, where four small temples had been built and two more were under construction. Both men and women tackled the slopes of the hillside with pickaxes and shovels, carrying the dirt away in wheelbarrows and (mostly) in metal pans which Indian laborers carry on their heads. "Moving the mountain" seemed an impossible task with those simple tools, but progress was noticeable week by week, if not day by day. Patience was one of the virtues which Babaji taught through experiences.

At noon, we stopped and washed in the river and sat in the warm sun on the cemented terrace outside the ashram kitchen to eat. There was half an hour or so to rest, then back to work until just before sundown. We washed or bathed and went to the evening aarati service. After the service, the kitchen crew served supper, generally left-overs from the noon prasad, but occasionally something freshly cooked. The ashram rule was that lights go out at 10 p.m., but there were many conversations held after supper until weariness put an end to them.

Margaret had come to my house in Washington shortly after the sudden death, from a bee sting, of my wife Jackie at the end of October 1978. Margaret was a teacher of Transcendental Meditation, looking for a job and a place to stay. I was then part of a State Department team negotiating the contract for construction of the new American Embassy compound in Moscow and I needed someone to house-and-cat-sit while I traveled back and forth before and after Christmas, 1978. By the time my travels were over, I found Margaret so charming and supportive that I had asked her to marry me. She didn't say "yes," but she stayed on in the house. Margaret, like Jackie and me, had read Paramahansa Yogananda's "Autobiography of a Yogi" and had been fascinated by the tales of Mahavatar Babaji. When she learned, in the summer of 1979, of Babaji's presence in Haidakhan, Margaret had decided to travel with Leonard Orr and a group of Rebirthers to meet Babaji in January 1980. I had helped her make the trip and Margaret was to have joined me on a post-retirement business trip through Europe and Israel to test the possibilities of establishing an international consulting firm. But when I got to London to meet Margaret on her return from Haidakhan, I found two letters from her saying that all she wanted to do was to spend the rest of her life in Babaji's presence; and thanks for everything. After a night of pondering what to do, I extended my airline ticket from Tel Aviv to New Delhi and cabled for an interview in the Ministry of External Affairs. It was in this way that I met Babaji somewhat earlier than my Capricornian schedule had contemplated.

In New Delhi, in Vrindaban, and during the ten days in Haidakhan, I tried to talk Margaret into returning to the United States and marriage, but she was firm in her desire to stay with Babaji. I grew more and more concerned with my need to pursue my consulting business proposal and, finally, headed back to the U.S.A. Margaret went with me to Delhi to see me off, but she would not go back to the United States with me.