Полная версия

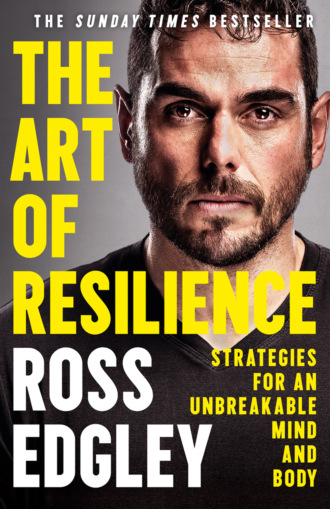

The Art of Resilience

I had been on our boat this morning doing a round of interviews with the media along with some local fishermen intrigued about my round Britain adventure. The tide had begun to turn, which signalled the media interviews were over and another swim was about to begin. As the journalists and fishermen left the boat, I sat in silence with Matt as I delicately attempted to put on my cold, clammy wetsuit over my tender and raw wounds. As I did, one lone writer lingered on deck and plucked up the courage to ask three final questions that would become integral to both the swim and this book:

‘Why are you doing this?

‘Why doesn’t your body break?’

‘How does your mind not quit?’

In truth, I was still trying to answer these questions for myself.

Fatigue and pain were deeply entrenched in each and every cell of my body, and as I sat there they were threatening to bring a stop to the swim. In front of the journalist, even though I was still not 100 per cent sure of the answers, I tried my very best to articulate the conclusion I’d come to so far after 74 days at sea.

‘I think the reason my body hasn’t broken and my mind hasn’t quit (yet) is because I’ve been able to fuse the teachings of ancient Greek philosophers with modern sport scientists to form my own form of philosophy called Stoic Sports Science.’

The journalist appeared puzzled at first but then nodded with his pen and notepad poised as if eagerly anticipating my next answer, hoping I was about to dispense some profound, deep and spiritual seafaring wisdom. But unfortunately, I had nothing else for him. Since I still had over 900 miles left to swim, my newly found philosophy was far from proven. But I told him if I completed the swim, I would finish my study and the book.

‘Then I’ll have to wait to buy a copy,’ he said laughing.

I smiled as we sat there taking in the vast expanse of our surroundings while pondering what had brought us together in this unlikely gathering.

‘Okay, why are you doing this then?’ he asked.

I looked at Matt. He looked back at me with knowing eyes. Nothing needed to be said.

The memory of the start of this journey (and life back on land) seemed like a lifetime ago. Many miles, tides and sunsets had passed since that day. But to understand why we were doing this, you must understand we as humans have been practising the art of resilience for centuries. It’s the one key trait we possess over all other species. Therefore, in many ways, what began on 1 June 2018 on the sands of Margate beach in southeast England was just an exaggerated expression of our unique human ability to find strength when suffering.

PART 1 | LIFE ON LAND (BEFORE THE SWIM)

CHAPTER 1 | WHY DID I DO IT?

LOCATION: Margate

DISTANCE COVERED: 0 miles

DAYS AT SEA: 0

It’s 7.00 a.m. on 1 June 2018 in the small coastal town of Margate. Tucked away on England’s southeast coast, this seaside resort has down the years served as a magnet for Londoners, with its sandy beaches less than 80 miles away from the capital. In fact, Margate has an old-world charm that makes the ice cream parlours, pie and mash shops and amusement arcades seem almost timeless. Yet the town’s history is also closely tied to the sea and the absence of their once great Victorian pier, destroyed after a storm in 1978, is a constant reminder to the locals (and all who visit) of the ocean’s power.

This is why the British coastline was the ideal ‘testing ground’ to research The Art of Resilience. Known around the globe for having some of the world’s most dangerous tides, waves and weather, every menacing whirlpool, rugged headland and North Sea storm would become a tool for me to sharpen my mind and harden my body.

But why Margate to start? When planning for the swim, we decided we needed to swim clockwise around Great Britain because the prevailing winds affecting our island are from the west or southwest. So we would be facing the ‘harder’ half of the journey – if we made it down the south coast, around Cornwall and up the Irish Sea towards western Scotland – during the summer months. The ‘easier’ half of the swim would theoretically be over the top of Scotland and down the east coast of Britain where we would be more sheltered from the southwesterlies by the topography of the coastline. Speed was of the essence, however, in order to complete our mission before the onset of winter.

But this morning, standing on the beach looking out to sea, I had absolutely no idea what lay ahead. Many people considered this ‘swimming suicide’, believing it was an impossible swim that was foolish to even attempt. But to quote the award-winning novelist Pearl S Buck, ‘The young do not know enough to be prudent, and therefore they attempt the impossible – and achieve it, generation after generation.’

Which is why my plan was simple. Using myself as a sea-dwelling, human guinea pig I would attempt to complete the first 1,780-mile swim in history all the way around Great Britain, while putting to test the science behind strength, stoicism and fortitude. As I researched the intricacies of resilience on this swim, my goal was to fully understand what makes the human spirit so unbreakable.

The regulations governing the swim were pretty straightforward too. It would be classed as ‘the world’s longest staged sea swim’ (where the distance of the individual stages can vary each day, and the start point of each stage begins at the finish point of the previous stage) and would abide by the rules of the World Open Water Swimming Association (WOWSA) and the Guinness Book of World Records. I would be fitted with an electronic GPS tracker and my location recorded with WOWSA at the end of each day’s swim. I would also tow an inflatable buoy during every swim for safety (especially at night, since it contained a flashing light so I could be seen). I myself insisted that I would not set foot on land during the entire swim, but would take my rest periods out on the water on a support boat.

Of course, this wasn’t a solo endeavour. To even contemplate a swim of this magnitude I needed a boat captain equipped with ironclad fortitude and years of experience sailing in the most adverse conditions Mother Nature could conjure up. Then I needed a crew with unwavering faith who would sail day and night alongside me, through hell and high water, to make this mission a success.

But instead of finding a team, I found something far better. I found a family.

The Knight family were a committed band of sailors and big-wave surfers who had the (joint) dream of sailing around Great Britain for many years. With a love of adventure and penchant for the impossible, dad, husband and captain Matt Knight was recommended to me by a mutual friend as the ideal man to lead my crew. When we first met down in Torquay to discuss the mission, he was struck by my enthusiasm and didn’t need much convincing to adopt an utterly naive and wildly optimistic swimmer and mastermind the first circumnavigation swim around this big rock we call Great Britain.

As a personality and a character Matt’s hard to explain, but let me try. Standing just over six foot, he was 60 years old but had a physique that resembled an elite triathlete. With not an ounce of body fat, he had giant, cartoon-like forearms that rivalled Popeye’s and skin like hardened leather from years of battling wind, waves and salt water. But these features were purely a physical representation of his deep connection with the sea, which all began in the 1980s when, as a young boy, he left his hometown in search of adventure and sailed across the Atlantic employed as a deckhand. Hardworking and with an insatiable love of the sea, he moved through the ranks; years later he gained his Yachtmaster qualification and skippered boats across the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian oceans.

Which is when he met mum, wife and chief cook, Suzanne, a petite, blonde Devonshire lady whose maternal instinct only seemed to be fulfilled when cooking for the family and crew while battling 20-ft waves somewhere across the high seas. In tandem with Matt, they sailed the coastlines of France, Cornwall, Devon, Wales, Ireland, Portugal and Madeira and explored some of the most remote islands in the South Pacific and Indonesia.

They even found time to produce four incredible children along the way, who would become the crew and my newly adopted brother and sisters: Taz, Harriet, Peony and Jemima. With no hierarchy, each one of my ‘sea siblings’ would do anything and everything possible to ensure we could continue making progress around the coast, from guiding me past lobster pots, jagged rocks and dangerous shipping lanes to guarding me from sharks, killer whales and seals during mating season.

Finally, I must mention my ‘home’ for 157 days. Hecate was a 53-ft (16-m) long and 23-ft (7-m) wide specially designed catamaran (known as a Wharram after its designer). Comprised of two parallel hulls that are essentially held together by rope and rigging, the entire boat bends, moves and contorts with the waves thanks to this form of traditional Polynesian boat-building that’s remained unchanged for thousands of years.

The idea for us on the swim was for Hecate to progress under sail as often as possible, but there would be times when travelling through rough seas or difficult tides that we would have to rely on her engine.

But the best part of Hecate? The galley. Serving as the kitchen and library, it was where most of this book was written. After swimming up to 12 hours per day, the remaining time I would spend eating, sleeping (dreaming) and writing about theories and philosophies in resilience that I’d been thinking about when staring at the bottom of the seabed. In fact, during the entire 157-day swim, we calculated I spent over 1,500 hours (over 60 days) swimming with my face down looking into the dark blue abyss, writing the chapters of this book in my own head before the words ever appeared on paper.

This is why the contents of this book have become a blend of:

Real-life events from the swim.

Stories from my past that influenced the swim.

Tales from the strange world of sensory deprivation that occurred in my head.

The one common theme that runs throughout is resilience. This was also inspired by research in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology which found, ‘The importance of intellectual talent to achievement in all professional domains is well established, but less is known about the importance of resilience. Defined as perseverance and passion for long-term goals … resilience did not relate positively to IQ, but demonstrated incremental predictive validity of success measures over and beyond IQ. These findings suggest that the achievement of difficult goals entails not only talent but also the sustained and focused application of talent over time.’1

Essentially, intelligence is great and being genetically gifted physically is an advantage. But one of the most underrated, yet powerful virtues a human can possess is resilience – which is exactly why I wanted to embark on this swim.

I wanted to follow in the footsteps of my hero Captain Matthew Webb, who, on 25 August 1875 achieved what many believed was impossible: the first crossing of the English Channel (swimming 21 miles from Dover in England to Calais in France). At the time, sailors claimed this was swimming suicide because the tides were too strong and the water too cold. But Captain Webb, in a woollen wetsuit and on a diet of brandy and beef broth, swam breaststroke (because front crawl was considered ‘ungentlemanly-like’ at the time) and battled waves for over 20 hours to make history.

I loved this story. It was one of grit, resilience and defying all odds as his dogged persistence and self-belief captured the spirit of the times and cemented Webb as a hero of the Victorian age.

Therefore, for me, circumnavigating Great Britain would serve as a way of reconnecting with these powerful and primitive human traits. Looking at the anthropology of us humans (and earth’s 4.5 billion-year history), it’s the reason we’re all here today sitting firmly at the top of the food chain, as we compete in the game that Charles Darwin and Herbert Spencer referred to as the survival of the fittest.

How did we do that? Well, our strategy has been simple. Around 100,000 years ago our ancestors developed these huge brains and amazing ability for endurance and physical labour and ever since have been able to outsmart, outhunt and outlast the bigger, stronger and faster members of the animal kingdom.

To them, bravery and tenacity weren’t rare and respected virtues. They were daily habits that people possessed solely in order to survive when everything outside of the comfort of their cave wanted to eat them.

Fast-forward to the era of modern (civilised) man and the same attributes of grit, determination and fortitude that saw us survive, now see us thrive. From the first ascent of Everest by Sir Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay in 1953 to Captain Matthew Webb’s first crossing of the English Channel, it seems this idea of persistence, valour and intestinal fortitude is what bonds great feats of human endeavour throughout history.

But today we are in danger. We are ignoring these key attributes that made us great as a species and are losing our ancient, age-old abilities for mental and physical robustness. Living between our desks at work and sofas at home, we would be almost unrecognisable to our intrepid forefathers who 70,000 years ago had dreams beyond their horizons as they left East Africa to explore the world. Which is exactly why I decided to swim around Great Britain and to write this book.

To show that we modern humans are capable of the same superhuman resilience as our intrepid ancestors.

CHAPTER 2 | WHY THE BODY DOES NOT BREAK

LOCATION: Margate

DISTANCE COVERED: 0 miles

DAYS AT SEA: 0

The clock strikes 2.00 p.m. on Margate beach and signals my final three hours on land.

I spent these last precious moments bouncing between the local patisseries and pizza parlours along the seafront, as a generous portion of scones, doughnuts and an 18-inch stuffed crust helped to calm my nerves. Not knowing when I might get a freshly cooked pizza again, I ate what I could and then put the rest in my pocket as I headed to the beach to meet the Mayor of Margate who’d kindly agreed to say a few words to me and the local media before we set sail.

Her name was Julie and she was lovely. Impeccably dressed and wearing a huge traditional gold medallion (known as a chain of office), she and her husband Ray had already met my mum and dad who’d arrived earlier that day. So, we skipped the formalities and instead spoke about scones and swimming and I ate pizza out of my pocket as they proudly told me about the history and heritage of their beloved town.

‘How long do you think it will take you?’ Julie asked.

I paused for a moment, since I really had no idea. All I knew was the waves, wind and weather would decide if and when I would finish. But as a very rough guess I replied, ‘Maybe a hundred days, but likely more.’

‘Oh dear,’ she said disappointed and looked at Ray with concern. ‘He’ll miss our food festivals in August if he doesn’t hurry.’

That one moment is why I will forever love Margate.

Marvellous Margate. Traditional and welcoming, but entirely unpretentious and down-to-earth. Whereas everyone else was concerned with the start, Julie was already (ambitiously) planning the finish to coincide with scones and jam at her local food festival. This is why I will be forever grateful to the town who waved me goodbye on my voyage.

But worth noting is that not everyone shared Julie’s optimism and there weren’t many people in attendance that day other than those who lived locally. Sponsors had tried their very best to get the national media to report on the start, but few were taking it seriously. Just months before, another swimmer had attempted the swim but quit after a week due to bad conditions. As a result, most journalists believed this was an equally ill-fated attempt at an impossible adventure.

Also, social media was rife with people posting why they thought this would fail.

Many believed the mind would quit …

Others believed the body would break …

But of all the naysayers, the most vocal were sports scientists within the swimming community who were quick to point out that my chunky five foot eight, 88 kg frame would never make it around; that with such short, stubby arms and legs it was obvious that the laws of hydrodynamics (the study of objects moving through the water) were not in my favour.

I was well aware of this, too. Months before arriving in Margate, I visited a sports laboratory for a full medical examination to see if my body could survive a swim of this magnitude. After hours of being prodded and probed I was told in no uncertain terms that I had ‘no physical attributes to be an elite swimmer’. They also added, I would likely, ‘sink like a stone’ if I embarked on this ill-fated swim.

But it gets worse …

Entering the room that day, the chief sports scientist picked up the clipboard containing my scan results. Looking me up and down he said, ‘You’re very heavy … but also very short.’

Harsh, but true, I thought.

‘That’s not good,’ he continued, now frowning as if the stubby statistics of my body were offending him and his laboratory. ‘But if I can be honest with you, it’s your body composition that concerns me the most. Since fat is buoyant and insulating, and you have very little, and muscle sinks, and you have a lot. Basically, floating and keeping warm is going to be an issue for you, never mind swimming.’

I nodded and thought this must be the most brutal assessment of a body in the history of swimming. But I wasn’t out of the woods yet. His confidence-crippling critique of my body continued and this time he had an issue with specific body parts.

‘Also, it’s your head,’ he continued.

‘What about my head?’ I said, now feeling a bit self-conscious.

‘It’s big and dense,’ he declared bluntly.

‘I know I’ve a big head, but—’ I was interrupted before I could defend my oversized cranium.

‘Yes, but it’s not just big. It’s very dense,’ he said gesturing with his hands. ‘In fact, all your bones are dense, but my concern is when swimming, because of the position and size of your head, you’re basically turning yourself into a human submarine, as the weight of your massive skull plummets you into the ocean bed.’

He then continued to flick through the pages of notes, surveying the metrics while continuing to tell me I had one of the densest skulls he’d ever seen. Moments later (and five pages in) we found a statistical silver-lining.

‘Oh wait,’ he said. ‘There might be some good news.’

I breathed a sigh of relief.

‘You have brilliant … fat … chunky … child-bearing hips.’

‘WHAT?’ I had no idea how this was good news, but decided it was better than a massive submarine skull so decided to listen.

‘You carry your fat around your thighs like a woman,’ he said, again gesturing with his hands. ‘What this means is despite your big heavy head sinking, your fat thighs will float … almost like a duck’s bum.’

He paused to consider his final diagnosis. ‘If you want my advice, I’d stop strength training. Lose muscle. Obtain a body that more closely resembles that of a swimmer. Then try and swim around Great Britain in a few years, because right now I’m not sure you could walk around never mind swim around.’

Sitting there, I agreed with everything he said apart from this hips ‘prescription’.

I do have a heavy head and child-bearing hips, but – completely contradictory to conventional sports science – I would argue that despite being a super-sized sumo-swimmer, these would uniquely equip me to swim around Great Britain.

Why was I so sure? Because his diagnosis was based on an elite swimmer competing in a 100 m or 10 km race and not someone attempting to swim 1,780 miles around several countries. This was the fundamental difference, since I was aware that being a leaner and lighter swimmer would make me faster, but I was also aware that being heavier and stronger would make me more robust.

Studies in strength agreed, too. Research from the National Strength and Conditioning Association (NSCA) stated, ‘When considering sports injury prevention strategies, the role of the strength and conditioning coach can extend beyond observing exercise technique and prescribing training to develop a robust and resilient athlete.’2

This is true in swimming and other sports. As early as 1986, research published in the Journal of Sports Medicine found that, ‘The incidence of various types of overuse injuries, such as swimmer’s shoulder and tennis elbow, may be reduced by the performance of resistance training activities.’3 How? Scientists added, ‘Resistance training promotes growth and/or increases in the strength of ligaments, tendons, tendon to bone and ligament to bone junction strength, joint cartilage and the connective tissue sheaths within muscle. Studies also demonstrate resistance training can cause increased bone mineral content and therefore may aid in prevention of skeletal injuries.’4

Now every athlete is, of course, different. Equally, there are thousands of incredible (and specific) treatments performed by world-leading physiotherapists, osteopaths and injury prevention specialists that are being used to treat thousands of specific intricate injuries, and in no way am I attempting to gloss over these. But evidence suggests – as you will see in a later chapter – that on a large scale across sports, countries, age groups and gender, strength training could hold the key to creating robust and resilient humans.

This (I believed) would be a deciding factor of the swim, because if I was to miss just a few days of perfect swimming conditions due to injury, I could also miss up to 100 miles of progress. Therefore, speed was an advantage, but physical resilience was a necessity.

Of course, many disagreed with this theory. But do you know who agreed with me? Barry. Yes, Barry always believed in me. A local fisherman from Margate, he was 65 years old and had lived here all his life. When news reached his local pub that someone was about to attempt to swim around Great Britain, he and his friend George came down to the harbour to watch the start of the swimming spectacle unfold.

Looking me up and down (like a short racehorse) Barry and George decided that there might be money to be made out of my little adventure. As they sipped their pints of locally brewed ale, they considered the terms of their wager and each gave their verdict on what they thought the outcome of the swim would be.

George approached me first. Very polite, but also very sceptical. He agreed with sports scientists from the swimming community and thought I might get 100 miles down the coast before my body broke or my mind gave up.

‘Young man, please don’t take offence,’ he said, looking up and down at my height (or lack of), ‘but based on how rough the sea gets on the south coast, I think you’ve just won me a hundred quid.’

Barry shook his head and disagreed, putting his arm around me as he said, ‘Go on, lad. I’ll get the beers in when you’re back.’

I laughed and gave Barry a big hug.

Again, this is why I love Margate. I thanked them both for coming as, regardless of the bet, they both showed up to wave me goodbye. But my parting words to Barry were, ‘I prefer cider to beer, but see you in a few months.’