Полная версия

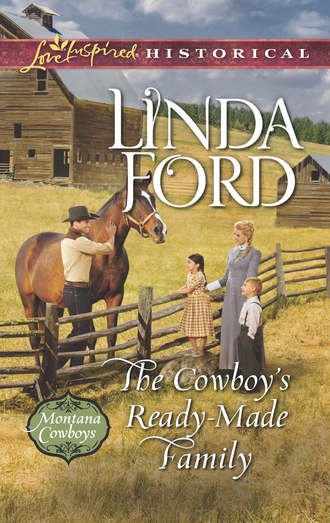

The Cowboy's Ready-Made Family

He rode past the farm, then stopped to look again at the corrals behind him. They were sturdy enough to hold wild horses...and he desperately needed such a corral... A thought began to form, but he squelched it. He couldn’t work here. Not with a woman with so many needs and so much resistance. Not with four white kids. Every man, woman and child in the area would protest about him associating with such fine white folk.

He shifted his gaze past the corrals to the overgrown garden spot and beyond to the field where a crop had been harvested last fall and stood waiting to be reseeded. He thought of the disorderly tack room. His gaze rested on the idle plow.

This family needed help. He needed corrals. Was it really that simple?

Only one way to find out. He rode back to the farm and dismounted to face a startled Miss Susanne. “Ma’am, I know you don’t want to accept help...”

Her lips pursed.

“But you have something I need so maybe we can help each other.”

Her eyes narrowed. She crossed her arms across her chest. “I don’t see how.”

He half smiled at the challenging tone of her voice. “Let me explain. I have wild horses to train and no place to train them.”

“How can that be? You live on a great big ranch.”

“My pa doesn’t want me bringing wild horses in.” He continued on without giving her a chance to ask any more questions. “But you have a set of corrals that’s ideal.”

For a moment she offered no comment, no question, then she finally spoke. “I fail to see how that would help me.”

“Let me suggest a deal. If you let me bring my horses here to work with them and—”

She opened her mouth to protest, but given that she hadn’t yet heard how she’d benefit he didn’t give her a chance to voice her objections.

“In return, I will plow your field and plant your crop.” The offer humbled him. He’d made no secret of the fact he didn’t intend to be a farmer. Ever. He only hoped his brothers never found out or they’d tease him endlessly. Even before he finished the thought, he knew they would. He’d simply have to ignore their comments.

“I have no desire to have a bunch of wild horses here. Someone is likely to get hurt.”

“You got another way of getting that crop in?” He gave her a second to contemplate that, then added softly, “How will you feed the livestock and provide for the children if you don’t?”

She turned away so he couldn’t see her face, but he didn’t need to in order to understand that she fought a war between her stubborn pride and her necessity.

Her shoulders sagged and she bowed her head. Slowly she came about to face him. “This morning I prayed that God would provide a way for me to get the crop in. Seems this must be an answer to my prayer.”

He was an answer to someone’s prayer? He kind of liked that. Maybe he should pray that God would make Himself plain to him. He’d sure like the answer to that prayer, as well.

“So I agree to your plan.” Her eyes flashed a warning. “With a few conditions.”

He stiffened, guarding his heart against the words he expected. Stay away from the children. Don’t think you can make yourself at home. Don’t forget you’re a half-breed. She might not use those exact words but the message would be the same.

“The children must be treated kindly at all times. And I don’t want them getting hurt because of the horses.”

His mouth fell slack. He was lost for words. Nothing about his heritage? Nothing at all?

“Ma’am, there is no need for such conditions. I would never be unkind to a child. Or an adult. Or an animal. Everyone deserves to be treated with respect. And I would never put anyone in danger. For any reason.”

She studied him for several heartbeats. She seemed to be searching beyond the obvious, but for what?

He met her look.

His mouth grew dry. He blinked and shifted away. He saw depths of need and a breadth of longings that left him both hungry to learn more and wishing he saw less.

“Then we have a deal.” She held her hand out.

He took it before she remembered he was a half-breed, and marveled at her firm grip despite the smallness of her hand.

Inside his heart, buried deep, pressed down hard beneath a world of caution, there bubbled to the surface a desire to protect.

The one thing he meant to protect was his heart. No one, especially a fragile blonde woman, would be allowed near it.

“We have a deal,” he said.

Their agreement would certainly solve two problems. But he wondered if it would create a whole lot more to take their place.

Chapter Two

A little later, Tanner rode into the yard at Sundown Ranch. His brothers trotted over to the barn as he led Scout in. Though they were close in age—Johnny was twenty, a year younger than Tanner, and Levi two years younger—his brothers were as different from Tanner as was possible. Johnny lived to please his father and to prove he was part of the white world. Levi didn’t much care what anyone except Maisie thought.

“You get them?” Johnny asked.

“I sure did. Ten in all. And all three of Ma’s horses. I have them in that little box canyon over the hill.”

Big Sam ambled into the barn. “Howdy, boys.”

“Hi, Pa,” they replied.

“You capture them horses?” he asked Tanner.

“Ten. Now all I got to do is break them.”

“Sure wish I could help you out, but you know my feelings.”

Tanner did. They all did. He could hardly wait to see their surprise when he announced his good news.

The supper bell rang and the four of them crossed to the house. It was a one-story structure, nothing fancy, but, as Big Sam often said with a great deal of pride, it was solid.

Maisie waited at the door to greet them. As part of her many rituals, she got a kiss on the cheek from each man as he passed. Not that Tanner was complaining. She was a good, loving mama to Big Sam’s boys and had never let their mixed heritage influence her affections for them.

They washed up, sat at the table and automatically reached for one another’s hands as Big Sam asked the blessing. Holding hands was another of Maisie’s rituals. He’d found the gesture comforting when he was eight and still found it comforting at twenty-one. There was one place he knew he belonged. Right here in this house.

They passed the food and then began another of Maisie’s rituals.

“Sam, did you get the cows moved up to summer pasture?” Over the evening meal, Maisie asked each of them about their day, starting with Pa and then proceeding in descending age.

“Sure did. Grass is looking good already. The cows will get lots to eat. Soon there will be calves on the ground.”

Tanner listened as Big Sam described every aspect of the herd. He’d grown up hearing this sort of thing and knew the importance of each detail.

When Pa was done, it was Tanner’s turn.

Maisie turned to him. “How did your day go? Did you get those horses you wanted?”

“Sure did.” Again, he told of his day, describing the horses in more detail for her than he had for his brothers or Pa.

“And I had a visitor.”

“Up there?” She sounded as surprised as his brothers looked.

“A young boy.” He enjoyed parceling out the information in a way that increased their curiosity.

Maisie sat back, dumbfounded. “What would a child be doing up there? How old was he?”

“Five.”

“That’s hardly more than a baby. Levi’s age when your mama died.” She gave Levi a look of love. It was no secret the two of them shared a special bond. She brought her attention back to Tanner. “Was he lost? Abandoned?”

“Nope. Just wandering a little far from home. It was Robbie Collins. You know, from Jim Collins’s farm.”

Maisie made a sound half distress, half regret. “Why, it’s—” She counted on her fingers. “It’s four months since he died. I’ve been meaning to get over there. I hear his sister is caring for the children. That poor girl. They say she hasn’t anyone to help. How are they faring?”

“I’d say she was struggling.”

“Sam, someone ought to help them.” Maisie shook her head, her look part pity, part scolding.

Tanner felt rather pleased that he’d be able to reassure her that someone was. “I have a set of corrals to work the horses.”

Maisie, Big Sam and his two brothers looked at him.

Big Sam found his voice first. “You built some already? How’d you manage that?”

“Didn’t build some. Found some ready and waiting.” He grinned at the curiosity his words triggered.

“Where?”

“How?”

“Are you joshing us?”

“At the Collins place. Pa, did you know Jim Collins had dreams of capturing some of the horses?”

Pa looked thoughtful. “Come to think of it, I might have heard him mention it a time or two. Took it as just that. Talk.”

“Nope. It wasn’t. He has a set of corrals over there that are just about perfect.”

Levi eyed his brother suspiciously. “How’s that going to work? You bought them? Rented them?”

“Traded for them.” He explained his work agreement with Susanne Collins. That brought a look of complete astonishment from those around the table.

“You’re going to farm?” Johnny shook his head. “Never thought I’d see the day.”

Tanner knew what Johnny meant. He’d often scoffed at stooping to join the white man in breaking the land and sowing crops. “It’ll be worth it to have the use of the corrals.”

As if sensing Tanner’s brothers might have a whole lot more to say about the subject, perhaps things Tanner didn’t care to hear, Maisie turned the conversation to Johnny, asking about his day.

Tanner listened with half his attention, his thoughts on his recent agreement. What had he done by agreeing to farm? He’d never been interested in hitching a horse to a plow, though he’d had to do it a few times as Pa insisted they grow oats for feed and wheat for flour. How many times had Tanner said his Lakota mother would have hated her sons in such a role? They should be on horseback hunting buffalo. But he hadn’t been thinking about that earlier today. In fact, all he’d been thinking when he suggested the agreement was what a shame that those corrals weren’t being used and that someone ought to help Susanne no matter how much she insisted she didn’t need it. There would be plenty of people saying he wasn’t the right sort of man to do it, but no other man had appeared on the scene in months. He’d be fair to her, though, and stay as far away from Susanne and the children as was humanly possible, considering the corrals were a few hundred feet from the house. Like it or not, they needed each other.

* * *

Susanne wanted nothing so much as to chase Tanner Harding down and tell him in no uncertain terms she couldn’t accept his plan. But the place was falling into rack and ruin. Jim had neglected it the past year or two as he dealt with Alice’s illness and then tried to cope with her death. Susanne would be the first to admit she needed help and she would hire a man in a snap if she had the funds to pay one.

She didn’t, so that left her no option but to accept help to get the crop into the ground. The rest of the work she’d manage on her own with the children’s help. Starting this morning. She called to them. “Let’s go fix the fence.” They wasted too much time every day chasing the cow and bringing her home.

The girls came readily enough, but Frank and Robbie stared toward the hill, no doubt curious about Tanner’s horses. She hadn’t seen them or his pen, but Robbie had provided a detailed description. She knew the place where he held the horses. Before Jim’s death, she’d loved wandering across the hills, finding wildflowers, watching hawks soar overhead and enjoying nature. She’d always felt close to God out there. She missed those times alone.

“Come on, boys.”

The pair had an animated discussion before they trotted toward her. She was certain the topic of their conversation was the wild horses. Robbie had talked of nothing else since Tanner had brought him back yesterday.

When they joined her, she caught Robbie’s chin and turned his face to her. “Robbie, I don’t want you going to see those horses. They’re dangerous. Besides, you shouldn’t be wandering about on your own. Something might happen.” Tanner had given no indication as to when he’d bring the horses to the corrals; nor when he’d turn his hand to planting the crop. She certainly had no intention of suggesting he should do it sooner rather than later, if she even saw him again. What was to stop him from riding in and out without acknowledging either her or their agreement?

She was getting suspicious. There was no point in blaming Aunt Ada for making her that way, even though the woman had assured Jim she’d give Susanne a good and loving home and she’d done quite the opposite. The experience had made Susanne cautious and more than a little suspicious of seemingly kind offers.

But that was in the past and she did not intend it to color her whole life.

“Yes, Auntie Susanne,” Robbie said.

With a kiss to his forehead, she released him. Each day he promised not to wander, but she knew he’d forget it if the urge hit him. So every day she reminded him again. Despite her frustration, she smiled at him and his siblings.

Each of the children handled the loss of their parents in different ways. Robbie wandered. Frank tried too hard to be a man. Liz looked for ways to make things go smoothly. Janie got lost in her dreams. Susanne often found her up a tree or tucked into a corner almost hidden from view talking to her doll.

And what did Susanne do? she asked herself.

She tried to take care of the work.

As she twisted wire together and tacked it to the wobbly post, she tried not to think too hard of all she’d lost. First her parents, then Alice and Jim. It was enough to make her certain she would never let herself care for another soul apart from these children, for fear of more loss. It was a strange world. Those who loved her died, while those who would use her to their own advantage lived to do so.

Never again, she vowed. She’d see to that.

She sought a more pleasant topic for her thoughts and settled on the diamond brooch Jim had given to her. It used to be their mother’s and before that, her mother’s. She and Jim had laughed together knowing the little stone in the setting was likely only glass. It didn’t matter. It represented their mother.

“You can hand it down to your eldest daughter,” he’d said.

She’d laughed. “What makes you think I’ll get married?”

He’d squeezed her shoulder. “You’re beautiful. You’ll have dozens of suitors calling.”

At the time, she’d been moved by his praise. Not since her parents died had she felt so blessed. But now it didn’t matter if she was beautiful or not. She’d not have suitors calling once they heard she had four children to raise as her own. She certainly didn’t count Alfred Morris. He was more of a dictator than a suitor. A man who wanted to own her. She knew he would constantly remind her how much she owed him for giving her a fine home.

She’d had enough of that.

And it wasn’t as if she’d have time for courting.

She’d thought a time or two of selling the brooch. But it was the only physical reminder she had of her mother and wasn’t worth a lot in the way of money. The diamond—if it was such—was so small she could barely see it. Instead, she’d trusted God to lead her to another way to manage.

She’d certainly not considered trading the corrals for seeding the crop and would still refuse if the good Lord would provide another way. Please, God, perhaps there’s an old married man who would work for a crop share. Straightening, she squinted toward the trail that led to town in the hopes of seeing a wagon headed her way. The breeze lifted a swirl of dust but nothing more. Seems that prayer was not to be answered at the moment. Anytime soon would do, Lord. She turned back to the fence.

A few minutes later, she twisted the last wire and straightened. “That should hold.”

“Can we go play now?” Robbie asked.

“Yes, you may.” She remained at the fence as they scampered off in various directions. “Don’t wander away,” she thought to call.

Alone for a few minutes and everything momentarily peaceful, she looked about and breathed deeply. She needed this time to think and pray. Father God, please help me keep the children. That means a way to do the farm work as well as time to tend to the children’s needs. Of course, God didn’t need the constant reminding, but she knew no other way to set her worries aside.

She could not linger, and hurried toward the house and the many tasks at hand.

The milk cow trotted away as she neared the yard and headed straight for the hole Susanne had just fixed. Seeing her way blocked, the cow mooed and shook her head.

“Too bad, old girl, you’ll have to stay in your pasture from now on.” Susanne entered the house and found Liz and Janie sitting at the table.

“Can we eat now?” Liz asked. “We’re hungry.”

Susanna didn’t need to look at the clock over the doorway to the living room to know the morning was almost gone and she’d accomplished so little. Being every bit as hungry as the children, she pulled out a frying pan, wiped it clean and set it on the stove to heat while she cut the leftover potatoes. Once they were browned, she broke in eggs. What did it matter if it was only eleven o’clock?

“Call your brothers and we’ll have dinner.”

When the boys clattered through the door, she told them to wash up.

She smiled at the way they bumped into each other. Two boys full of energy and playfulness. Guilt stung her throat. When Jim was alive, he’d romped with them, and she’d played quiet games with them. But it had been weeks since she’d had time to play with any of them.

Susanne put the pan in the middle of the table and looked at Liz and Janie on one side, Frank and Robbie on the other. Her gaze lingered on the vacant spot at the end where Jim used to sit. She swallowed hard, missing him yet feeling blessed by the presence of the children. “Let us pray.” Her voice caught on the words.

The children obediently clasped their hands together under their chins and bowed their heads.

“Lord, we are so blessed to have each other and to have food to eat. Thank You. Amen.”

“Amen!” Frank added with so much enthusiasm that Susanne chuckled.

“It’s not like you’ve been starving to death.” She again felt a sting of guilt. Her meals were simple fare. She lacked time for anything else.

She really should do more cooking. Make bread again. It was weeks since they’d had anything but biscuits and fry cakes. Not that both weren’t perfectly adequate. Just as fried potatoes and eggs were perfectly fine for a meal. Perhaps not day after day, an inner voice suggested. Susanne promised herself she’d do better...once she got the work on the farm taken care of.

“Robbie, slow down.” The child ate as if it was a race.

Frank spoke slowly. “I’m glad Tanner is going to bring his horses here. Pa would have liked that.” Frank’s jaw grew firm, reminding her of Jim. Tears caught in the back of her throat. She’d waited so long to be reunited with her brother only to lose him again. At least until she got to heaven.

“He planned to capture some of the wild horses himself,” Frank explained.

Susanne knew that. In fact, he might well be alive today if not for that dream. He had been following the whereabouts of the herd when he got caught in a downpour that eventually led to his pneumonia.

Frank continued. “He had the corrals all ready and would have gotten his horses for sure except Ma got sick and then he got sick.” His voice quavered but he pushed on. “He told me I could help him when he got the horses. He’d have to gentle them first, but then I could help feed them and could talk to them so they’d learn not to be afraid of children.” Frank sucked in a ragged breath, as did his brother and sisters. This talk of their father and mother would soon have them all in tears. “I want to help Tanner with the horses.”

Susanne jolted back. “I’m sorry, but I must refuse you permission. It simply wouldn’t be safe and I sure don’t want anything to happen to any of you.”

Frank hung his head but not before she caught a glimpse of rebellion in his eyes.

She’d never considered she’d encounter problems with the children. But she must insist. Being around wild horses simply wasn’t safe.

The children were subdued throughout the remainder of the meal. Afterward they helped with the dishes, then scattered outside. She should give them more chores but couldn’t seem to get any organized for them and she freely admitted she didn’t want them to have to work as hard as she had for Aunt Ada.

She glanced about the kitchen. It needed a good cleaning. Alice would be shocked at the way it looked, and Aunt Ada would have had her whipped for the neglect.

But she no longer answered to Aunt Ada or depended on her for a roof over her head and a meal to warm her insides.

She stepped outside when she heard a horse approach. Goodness, months had gone by without anyone but Alfred Morris visiting, and now she had a steady stream of visitors. Or rather, she corrected herself as she recognized the rider, one recurring visitor. Was this what she’d agreed to? For Tanner Harding to come and go at will? Her insides grew brittle at the idea. Frequent visitors, in her mind, came with demands. Demands she didn’t care to fulfill. Thinking of Mr. Befus, she shuddered.

Her eyes narrowed as she saw the milk cow bawling and bucking behind Tanner, protesting at being pulled home at the end of a rope. What was he doing with her cow?

“I brought you something,” he said, jerking his thumb in the direction of the cow.

“Was she out? I fixed the fence just a few hours ago.”

“I saw her jump over the fence where the wires were slack. She was intent on the wide-open spaces.”

“What am I going to do with her?”

“You could try tethering her.”

She hadn’t meant the question for him but if he knew how to keep the cow home, she would like to know. “How do you do that?”

“I’ll show you.” He led the cow toward the barn.

“You tell me and I can do it myself.” Susanne followed hard on his heels, intent on making it clear she didn’t need his help. She did not want him to think he could take advantage of her failures.

“You’re back,” Robbie called to Tanner.

The four children stood in the doorway of the barn, their faces eager.

“I brought your cow home.”

“She won’t stay,” Frank said.

“That’s our problem,” Susanne pointed out, not wanting Tanner to think she couldn’t manage. Never mind that there was plenty of proof she wasn’t doing well on her own.

Ignoring her protests, Tanner handed the rope to Frank and went into the tack room, picking his way over the items on the floor.

Susanne’s cheeks burned. She’d been meaning to clean up that mess. Another of the chores that never seemed to get done.

Tanner returned, a halter in his hands, and went to the cow, five people watching him, four with keen interest, one with reluctance. Okay, maybe she’d let him do it this time, while she watched and learned. After that, she’d do it herself.

“Let’s see if we can train her to stay home.” He slipped the halter over her head, found a length of rope on a nail by the door and hooked it to the halter.

“It’s long enough we can secure it to anything solid enough to hold her. Which might have to be a tree with a girth of at least six feet.”

The children giggled at his explanation as they followed him from the barn. The cow balked, but he leaned into the rope and persuaded her to walk along.

Could this control the stubborn animal? It must. She had no other choice.

“That tree will do.” He led them to the spot where the grass was green and the tree stout, and tied the rope about the tree. “Now she needs water.”

“I’ll get it.” Frank ran back to the barn and dragged out a small trough. He put it beside the tree and then hurried to fill it with water.