Полная версия

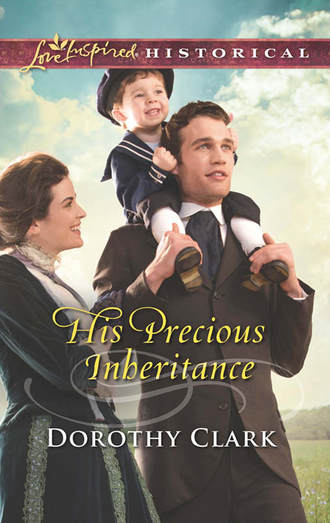

His Precious Inheritance

“How will you have time to answer all of those letters when you begin teaching?”

She shoved away the bitter memories. “I’m going to resign my position. I will earn more answering those letters every month than I would earn as a teacher. And more yet by writing my monthly column. And doing so will further my career.”

Oh, how wonderful that sounded! She snatched up her wrapper, put it on and crossed to the dressing table to pull the pins from her hair. Soft, dull clinks accompanied their drop into a small pewter dish. “And he has a typewriter I will use!”

“A ‘typewriter’?” Her mother’s questioning gaze fastened on hers in the mirror. “What is a typewriter?”

“It’s a machine that prints letters on a piece of paper when you depress a round button. I saw a picture of one once in an advertisement. Mr. Thornberg says that when a person becomes proficient in its use, they can write—type—up to eighty words a minute.” She stared into the distance trying to imagine it, then ran her hands through her hair and set the long silky tresses rippling free. “And that is another bles—benefit. I am to be at the newspaper tomorrow morning at eight to begin my work.” She ran her brush through her hair, looked at her mother and smiled. “The Journal building is close by, and unless Mr. Thornberg objects, I will be able to come home and see you at dinnertime. And I will be here with you for supper and every evening.”

She slipped a length of ribbon between her neck and her hair, tied it and stepped over to the bed. “Lean forward and I will rub your back, Mama.” She pulled the pillows out of her way, handed them to her mother, then massaged the muscles along her spine, frowning at the bony protrusions. Her mother was much too thin from all that hard work. Her face tightened. She thrust aside the infuriating memories. Her mother would never have to do such heavy lifting again. If only she could walk. But at least she was no longer in constant pain.

“That feels good, Clarice. It takes away the ache. Thank you.”

“My pleasure, Mama.” She lifted her hands and massaged her mother’s bony shoulders and thin neck, wished it were her father beneath her hands. She would pummel him until he ached and be glad for doing it. She took a breath, reached for the pillows and punched them instead. “I’m sorry I had to leave you alone so soon after bringing you here, Mama. How was your day with Mrs. Duncan? Did she help with your personal needs all right? Did she bring you your meals?”

“Everything worked out fine, Clarice. Mrs. Duncan and I chatted like old friends. I enjoyed her company. I—”

She glanced at her mother’s tightly pressed lips, tucked the pillows in place and finished the sentence for her. “You never had visitors on the farm. Father scared them all away, except for Miss Hartmore.”

“Yes. God bless Miss Hartmore for her courage in rescuing you.”

It was a prayer. She said it, too, every time she thought of her old teacher. The difference was her mother believed God heard and answered prayer—for her it was an expression of gratitude.

“And you, Mama.”

“And me.” Her mother shivered and smoothed the wrinkles from the quilt covering her legs. “What sort of man is Mr. Thornberg?”

The question caught her off guard. “I don’t know, Mama. I only spoke with him for a few minutes.” She thought about his handsome, strong-featured face. There was nothing soft about Mr. Thornberg, but he seemed eminently fair...even generous. Of course, he hadn’t any choice. “He’s strong, with decisive ways.”

Her mother grabbed her arm. “Don’t anger him, Clarice. If he does not want you to come home for dinner, I will be fine with Mrs. Duncan.”

Her chest tightened. “You don’t have to be afraid for me, Mama. Mr. Thornberg is a bit autocratic—as men are. But he’s no despot. And I’m certainly in no physical danger.” An image of Mr. Thornberg towering over her as she stuffed letters into the bag he held flashed into her head. He was a big man—like her father. Odd that she hadn’t been frightened. Likely she’d been too focused on his job offer. She hid her shiver and smiled reassurance. “He’s a businessman with socially acceptable manners. He would never hit a woman. It would ruin his reputation.”

Her mother nodded and rested back against the fluffed pillows, but the remnant of past fear shadowed her blue eyes. “Just be careful, and do as Mr. Thornberg says, Clarice. I can’t protect you anymore.”

She turned her mind from all the times her mother had stepped in and taken a blow meant for her from her father’s hand, swallowed hard and pushed words out of her constricted throat. “There’s no need, Mama. You and I are here together, and I will take care of us both. No man will ever hurt either of us again. I promise you. Not ever.”

* * *

Charles tightened the screw in the wobbly table leg, tossed the screwdriver down and rose to shove the end of the table against the wall. “Ugh!” He ducked, rubbed the top of his head and shot a look upward. The three-lamp chandelier overhead was swinging. There were six of the traps for the tall and unwary hanging evenly spaced in two rows that ran the length of the room. One chandelier for each of the desks for the six reporters he hoped to need someday. So far he had one reporter—two counting himself—and a correspondence secretary acquired quite by accident. Well, accidental necessity. The deal he had made to edit and print the Assembly Herald newsletter was not quite as good as he had expected it to be, thanks to those letters. But he would still profit by it.

He tugged the chain to lift the weights and lower the light closer to the work surface, then glanced across the width of the room to the new black walnut typewriter desk sitting at a right angle to the outside wall. Miss Gordon would be out of the way there at the back of the editorial room. And the desk was handy to the shelves on the back wall that held reference books and supplies, and also to this table he had brought in to give her a place to sort those letters. She was going to need it.

He lifted the overstuffed burlap bag from where it leaned against the inside wall to the tabletop. Letters spilled out of the mouth of the bag onto the waxed wood when he let go. Curiosity reared. He picked up an envelope, broke the seal and scanned the contents.

Dear Chautauqua Literary and Scientific Circle teacher,

I have been doing my studying and reading and have come across these words I don’t understand or know how to properly say. There is no library near me where I can look them up in a dictionary. Would you help me, please? The words are phenomena and pantheists.

Also, please, how do you say these names correctly? Leucippus and Democritus.

Thank you for helping me.

Chautauqua Literary and Scientific Circle member Martha Hewitt, Burgessville, Iowa

He laid the letter on the table, lifted his hand and rubbed the muscles at the back of his neck. How would Miss Gordon ever manage to answer all of these letters in a column? It would take an entire page or more. He shook his head, strode to the door that opened into the composing room and continued on to the long, deep table that held the uncrated typewriters.

Miss Gordon had tried to hide her excitement at his mention that she would use a typewriter, but her eyes had betrayed her. Their gray color had warmed and those blue flecks had glowed with anticipation. And then she had challenged him.

He picked up one of the three typewriters and headed for her desk. How enthused and confident would Miss Gordon be when she saw the complex machine? Not to mention the thirteen-page brochure of directions on how to use and care for it. He would most likely have to help her in the beginning. Women weren’t meant to work with machines. It wasn’t their forte. They were best suited for caring for a home and a family. At least, most of them. His face went taut. He shoved away thoughts of his mother.

He settled the typewriter on the pullout shelf, tested it a couple of times to make certain it remained stable. Odd that Miss Gordon was yet unmarried. She wasn’t unattractive. It was her plain manner of dress and that cool, standoffish attitude she manifested that made one think so. Still, when she smiled...

He shook his head to rid himself of the image, strode back to the composing room, picked up another of the new typewriters and carried it to Boyd Willard’s desk in the front corner facing the stairwell. The reporter pounded up and down those stairs chasing after stories all day long and his comings and goings were less of a distraction with his desk in the front corner.

Boyd wasn’t too keen on learning to use a typewriter, but he’d given him no choice. He wanted a modern, efficient newspaper and employees who would fit in with his plans. If Boyd continued to balk, he’d fire him and hire someone willing to learn modern ways.

One more. He carried the last typewriter to his desk, looked around and smiled. The new machines gave the editorial room a modern, businesslike look. He distributed the manuals that had come with the machines to the other desks, plopped down in his desk chair and opened his. He might as well get a head start so he’d have the answers when Miss Gordon came to him looking for help.

He scanned the information about setting the machines in place and skipped down the page. Machines are packed and shipped, properly adjusted and ready for use. Good to know. Placing the Paper. Ah, this was the information he needed.

He grabbed a piece of paper off the pile sitting on his desk and read the instructions. Lay the paper upon the paper shelf (F) with the edge close down between the cylinder and the feed roll...

* * *

Clarice turned onto the stone walkway and glanced again at the impressive building. The morning sun shone on the brick, warmed the gray stone that framed the doors and windows and formed the legend Jamestown Journal above the second-story windows. She worked here! Her dream come true. Almost. The word calmed her rush of nerves. It was true Mr. Thornberg had hired her, but her work was for the Assembly Herald, not for the Journal. Still, she would be working here at the newspaper building every day. The chance for her to prove herself as a journalist would come.

She took a deep breath, lifted the hem of her skirt and climbed the two steps to the large stoop. A long window in the wide paneled door reflected her image, the small white dots on the bodice of her midnight-blue day dress twinkling like stars in a night sky as she moved forward. She stole a quick glance to be sure every strand of hair was swept into the thick coil on the back of her head, then opened the door and stepped into a large entrance hall. There was a strange scent in the air—faintly metallic, rather...stale, though not like food. She sniffed, then sniffed again but couldn’t identify it. She turned toward the open door on her left marked Office and stepped inside. The odd scent grew stronger.

A portly man with a bald spot and bushy gray eyebrows above eyes with squint lines at their corners turned from the counter he was leaning on and peered at her. She glanced at his ink-stained fingers and the black blotches smearing his leather apron. Printer’s ink. That’s what that smell was.

“May I help you, miss?”

“Yes, thank you. I’m looking for Mr. Thorn—”

“Here’s the copy for that advertisement, Clicker.” Charles Thornberg came striding out of what she took to be an inner office, glanced her way and stopped short. He handed the paper in his hand to the portly man. “Mr. Gustafson wants twenty posters. He’ll send someone to pick them up this afternoon.”

The printer nodded and hurried out the door beside her.

Her nose twitched as he passed by. It was the ink.

“You are prompt, Miss Gordon.”

There was an underlying note in Charles Thornberg’s voice that suggested he was surprised by the fact. Because she was a woman? What other reason would he have? She gave him a cool look. “It is my belief that tardiness shows a flagrant disregard for another’s time. It has no place in the business world, Mr. Thornberg.”

His left brow rose. “An admirable point of view, Miss Gordon.” He came around the desk, gestured toward the door. “If you will come with me, I will show you to your desk so you are not delayed in your work.”

Was he gibing her for having an opinion? She swallowed the desire to ask him if he would have addressed a man thus, lifted her chin and preceded him out of the door then waited for his direction.

“This way, please.”

She followed him down the entrance room, through a door with a No Admittance sign and into a wide hallway. The odor of printer ink, much stronger in the smaller space, mingled with another somewhat rancid chemical smell.

“That is the...er...‘necessary.’” Mr. Thornberg waved a hand toward a door opposite the one through which they had entered, then turned to the right and motioned to a door in the end wall. “Those chemicals you smell are from the photography room. It’s located inside the printing room—Clicker’s domain, which one enters at his peril.”

His lips slanted in a wry grin that was utterly charming and impossible to withstand. She tried, but her traitorous lips curved in response.

He pivoted and strode toward the room then stopped at the base of a wide stairwell on his right. “We’ll go upstairs.” He moved to the far edge and waited.

A muted clicking came from the printing room. She shot a sidelong look toward the door, wishing he would take her in there to see how the printing was done. Perhaps if she were a man, he would have. Was that why he had warned her away? Because she was a woman? Her father had no such problem in assigning her man’s work on the farm. Her face tightened. She took hold of the railing, lifted her hems with her left hand and started to climb, the whisper of the short train of her long skirt against the polished wood accompanied by the taunting clicking sound. Mr. Thornberg fell into step beside her. Her stomach tensed at his closeness. She forced herself to maintain a dignified pace instead of bolting ahead to put space between them.

“The stairway divides at the landing. The steps on the right go to the composing room. We’ll take the left side that goes to the editorial room.”

She nodded, crossed the landing to the left side and began to climb the second flight of stairs. Sunlight poured in a window on their right, making the polished oak treads glow. She stepped off the stairs onto the oak floor, turned toward the room and stared. “It’s—it’s huge.”

“I built for the future. This town will grow and I expect to need the space for more reporters when the paper increases in circulation.”

More reporters. Her heart skipped. Oh, God, please, let me be— She squelched the spontaneous prayer. Even after years of knowing it was simply a waste of time, the urge to pray rose from her heart during unguarded moments. She glanced at the morning sunlight pouring in the four large windows in the long side wall. “It’s wonderfully bright in here.”

“Yes. I wanted to capture all the natural light I could. There’s little enough on stormy, rainy days or in the winter when it turns dark early. But I had chandeliers hung over each desk to take care of that problem—or for when there’s an emergency of some sort and we have to work nights to get the story written and printed.”

“That sounds challenging.” She glanced up at the chandeliers hanging by loops of chain from the ceiling and took a step to the side. Not all men were cruel like her father and brothers, but being alone with one still unnerved her. It was a situation she tried to avoid. “It seems you’ve thought of everything.”

“I’ve tried. But I’m sure there will come some point in the future when I’ll discover something else was needed.”

She stole a surprised glance at him through her lowered lashes. Where was the supercilious male attitude that had been so apparent?

He moved forward, gestured to the right, then to the left. “That is Boyd Willard’s desk—he’s my reporter. This is mine.”

His? Didn’t he have an office?

“This area is empty at the moment.” His lips slanted in another of those charming grins. “It will hold the desks for those reporters of the future.”

“I’m sure it will, Mr. Thornberg.” She wasn’t sure why she uttered the reassuring words, or even if she meant them for him or for herself. It just seemed that somehow her dream of one day being a journalist blended with his dream of one day having a thriving newspaper. His patronizing attitude toward women in the workplace was a little daunting as far as her dream went, but biting her tongue when a retort sprang to her lips and working hard should change that. Her writing ability would speak for itself.

“Yes. Well... Through this doorway is the composing room.” He motioned her ahead of him.

She stepped into the adjoining room, swept her gaze over three of the largest tables she had ever seen. On the opposite wall, between the windows, three hangers with serrated-edged cutters held wide, thick rolls of white paper. Supplies too numerous to take in and give name to filled floor-to-ceiling shelves that framed two windows on the back wall. She longed to go and peek in the boxes and small wood crates, to open the stoppered bottles and jars and find out what treasures they held. “This is where you design and lay out the pages the way you wish them to appear in the newspaper?” She moved forward to the center table and ran her hand over the smooth surface, imagining the process.

“Yes.”

A small box filled with pieces of paper with writing on them sat at the end of the table. “What are these?”

“Fillers.”

She looked up at him.

“They hold snippets of information, usually historical in nature—recipes, gardening hints, that sort of thing.” He stepped to her side, reached into the basket and pulled out a few of the pieces. “As you can see, they are different widths and lengths.” He glanced at her, then looked down at the papers he’d spread on the table. “Stories or articles or advertisements don’t always fill a column or allotted block, and you don’t want empty space on a newspaper page, so you choose one of these of the right length that will match the width of the column and use it to ‘fill’ that area.”

“I see.” She stared down at the filler pieces, touched the one touting “Indian Pudding.” Her pulse quickened. “Who writes these?”

“There was an ample supply of them when I bought the paper, but they’re running low. I’ve only enough for a few weeks left. I’ll see about making more soon.” He swept the pieces together and tossed them back in the box. “I’ll show you to your desk.”

Her desk. Her stomach flopped. She pressed her hand against it and followed him back into the editorial room.

“I put this table here for your use. I presumed you will need a place to sort through all of those letters.”

She followed the sweep of Mr. Thornberg’s hand and eyed the burlap bag with letters spilling out of it lying on its side on the table. “That was very thoughtful. Thank you.”

He nodded and moved on, stopped.

Sunlight pouring in the last of four windows in the outside wall shone on the polished wood of a low hooped-back chair with a red pad and a beautiful desk with six drawers. But it was the box on top that made her pulse race. Did it contain a typewriter?

“I placed your desk here close to the shelves of our research materials on the back wall, where it would be handy for you.”

Another thoughtful gesture. She tugged her gaze from the box and looked at the shelves, stared in amazement at the treasure trove of rich leather-backed books.

“There is a dictionary and thesaurus, of course, along with other research books. Volumes of literature and poetry...books on history and the sciences...legal books...a Bible and concordance, of course...maps... There are also office and writing supplies. And now typewriter supplies, as well. You’ll not need them to start, however.”

Her heart sank. She promptly took herself to task for her attitude. So she wouldn’t have a typewriter of her own. She had a job as a columnist, and she would work here in the editorial room of a newspaper, and she was free to use one of the other typewriters when—

“The machines come adjusted and ready for use.”

Her heart all but stopped when he reached down and grasped the front of the box. He opened the hinged front sections out to the side like double doors and a typewriter sat there, sunlight gleaming on the metal, shining on the round white keys and warming the narrow wood bar at the bottom front. Her breath caught. It was the most beautiful thing she’d ever seen. Her fingers tingled to touch it.

“The shelf the machine sits on pulls out and locks in place when you wish to type—like this.” He slid the shelf forward. “When you are finished with your work, you unlock the shelf and push it back, thus...” He demonstrated, then straightened and stepped back. “I believe that is all I need show you, Miss Gordon.” His gaze fastened on hers. “I think it best if you learn how to use and care for the machine on your own. I will, of course, be ready to answer any questions you may have or give you any help you require. You may feel free to interrupt my work at any time—while you are learning about the typewriter. I trust it will not take more than a few days.”

His tone said he expected there would be quite a few interruptions. She stiffened and lowered her gaze back to the typewriter. If a man could learn to use it, so could she!

“I placed the direction manual on the machine’s use and care in the top right-hand drawer of your desk, along with paper for its use.”

There were directions! She gave an inward sigh of relief.

“Any other writing supplies you might need are on the shelves. I felt it best if you arrange your desk as you wish.”

“That is very considerate of you, Mr. Thornberg.” And not at all autocratic. She shoved aside her surprise. He must have a reason. No doubt all of those letters! “Thank you...for everything.”

“Not at all, Miss Gordon. I trust you will find all of the research material you need on the shelves. However, if you come upon a CLSC member’s question you cannot find the answer to, you are to come to me. If necessary, I will purchase the needed resource material.”

If necessary. The stiffness shot back into her spine. He might as well say straight out that he was certain he would be able to supply the answer to any question she found it necessary to bring to him. Well, she would wear her legs down to stubs walking to the public library to find any answer she might need before she would walk the few feet to Mr. high-and-mighty-superior-male Thornberg’s desk!

“I shall leave you to your work now, Miss Gordon. I will be at my desk or in the composing room whe—should you need me.”

She watched him walk away, then sat in the chair and slid the typewriter shelf toward her. The metal was cold to her touch, but, oh, how the feel of those round white keys warmed her. She pulled out the direction manual, cast a surreptitious look at the surprisingly thoughtful Mr. Thornberg and began to read.

* * *

Charles glanced toward Miss Gordon’s desk, frowned and directed his gaze back down to the article he was editing. He scanned the words, looking for the spot where he’d been reading... those who use science...spiritual existence...one truth can never contradict another... Ah. There it was. ...accustom people to... Now, what was she doing?

He scowled and put down his pen. The carriage on Miss Gordon’s typewriter was lifted and she leaned forward peering down into the works, the manual in her hand. Why didn’t she come to him with her questions? She had to have questions.

Her head lifted and their gazes met. His gut tightened. She gave him a tentative smile and went back to whatever she was doing with the typewriter, but the look in her eyes had said more clearly than words that she was uncomfortable with his attention. It was the same look she’d given him when she’d caught him looking at her aboard the Griffith. The woman made him feel like some lecher, and that would end right now! He sucked in air, shoved his chair back and rose. “Miss Gordon...” Her head lifted again and her unusual, expressive gray eyes fastened on him, uneasiness shadowing their depths.