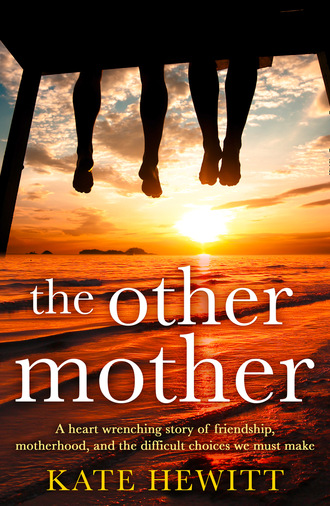

Полная версия

The Other Mother

“Why can’t you?” he asks.

“Have you been to my apartment?” I try to joke, but it falls flat. “Look, I’m not like you guys. We know that. I’m single, I have no savings, my apartment is a sixth-floor walk-up…” I shake my head. “I want my child to have more than that.” It sounds kind of lame and superficial, but it’s true. I think.

“Let’s forget about all the obstacles for a moment,” Rob says. “The real question, Alex, is do you want to keep this baby? Because if you do, then we can explore ways we can support you in that.”

I can hear the silence from Martha; it’s like a pulsating, living thing. Rob is smiling at me kindly, but I see the worry in his eyes and I know what he’s really thinking. He wants me to be sure. Well, duh. If I’m not sure, if I change my mind, I’d break both their hearts.

I’m not going to change my mind. Which is why it’s taking me so long to say yes.

“That’s really nice of you, Rob,” I say, and my voice sounds clogged again. “But it’s not really about the money or my apartment. Those are excuses.” I take a deep breath. “It’s about me.” And it hurts to say that. “I don’t think—I mean, my life is—” I stop, take a breath as thoughts and images flash through my mind. My tiny, messy apartment, my carefree life, the two abortions that I never even thought about but somehow now make me ache. “I’m not really mom material, you know?”

Neither of them says anything. I try to smile. “And I want to do this for you. You guys are so great, and you’ve been wanting a baby for so long…” I trail off, near tears again. “I really would love to make you happy,” I finish, and even though I am near tears—and not happy ones—I do mean it.

Rob gazes at me steadily, but he looks pretty emotional too. “Maybe you should think about it for a while.”

“I have thought about it. A lot.” I don’t want to go back to my crappy apartment and see all the potential child hazards. I don’t want to scroll through my life in my mind and realize how a baby could never, ever fit into it. I don’t want to feel as if my choices have been mistakes.

So I take a breath, and then I say it. “I’d like for you and Martha to adopt this baby.”

Martha lets out a rush of breath and Rob nods slowly. “I’d still like you to think about it for a while.”

“Rob—” Martha sounds exasperated, almost pleading, and I understand because I feel the same way.

“That’s really nice of you,” I say again, “but I am sure.” I give a wobbly smile that feels as if it could slide right off my face. “Being sure doesn’t mean I’m not going to be emotional, you know.”

“I know. This is emotional for all of us.” Rob lets out a shaky laugh, and we sit and stare at each other, all of us wondering, What now?

Then, to my complete surprise, Martha lurches off her chair and comes over and hugs me. I can feel the sharp angle of her collarbone pressing into my shoulder. “Thank you,” she whispers against my hair, and a tear trickles down my cheek as my doubts, in this moment at least, fall away.

Chapter 7

MARTHA

When I put my arms around Alex surprise jolts through me. This is not me. I acted on impulse, an impulse I never have, and I can feel the tension in Alex’s body at my embrace, and then it slowly dissipates and she hugs me back.

Okay, enough. I disengage as gently as I can, smiling even though part of me feels like crying out of pure emotion. I am going to have a child of my own. I’ll hold her—I’m already thinking of the baby as a girl—the day she’s born. The minute she’s born, because I want to be there when Alex delivers. There are so many things I want, and they are tumbling through my mind and crowding in my mouth but I force it all back. Too soon. I know that.

“Okay.” Rob smiles at Alex and leans back in his chair, his hands on his thighs. “Well, we have plenty of time to figure out how this is all going to work. Plenty of time.”

And I nod as if I agree, because I don’t want to freak Alex out, but my mind is racing, racing. I am thinking about her pregnancy, and how everything has changed because she is now carrying my baby, but I want to be respectful and I definitely don’t want to push. A sudden thought flits through my brain and pops out of my mouth.

“Have you talked to the father?”

Alex’s mouth quirks in a sad little smile. “Yes.”

“And he’s—he’s okay with adoption?”

“Yes.” A pause and she glances down at her lap. “It’s Matt.”

It takes me a few seconds to place the name, and then I remember an old boyfriend of hers from years ago—I met him a couple of times—and the first thing that flashes through my mind is relief. I know Matt. He’s a good guy. He has good genes.

Is it awful for me to think that way? Is it wrong?

“Well, that’s good,” Rob says into the silence. “I think, legally, you might need his consent before you sign the adoption papers.”

And suddenly it’s as if he’s thrown a bomb into the middle of the room, he’s lobbed a hand grenade and it lies there on the floor, waiting to detonate and spill out all its ugly words. Words like legally.

Because this is—this will become—a legal transaction, and there will be papers to sign and rights to give up and, no matter how friendly we are, how much we like each other, it will be uncomfortable. Painful.

“Of course,” Rob says, and I think he realizes he shouldn’t have gone there so quickly, “that’s a long way away. We don’t even have to think about any of that until you’re close to delivering.” Alex nods and he continues, his voice turning just a little too hearty, “The important thing now is that you stay healthy. That the baby stays healthy.”

And I’m racing ahead again, wondering if I can recommend an OB. Would it be rude to ask her if she’s taking folic acid supplements? And what about prenatal yoga?

We don’t talk much more after that, and eventually Alex leaves. Already it feels a little awkward, although I feel as if it shouldn’t. We’re friends, after all. I touch her shoulder at the door, wanting somehow to convey how much I appreciate what she’s doing, how happy I am.

“This is such a great thing you’re doing, Alex,” I say. “This is such a gift.”

She smiles at me, although she still seems a little teary. “You’ll make a great mom, Martha,” she says, but there is a note in her voice that makes me feel as if she is thinking she wouldn’t. And I want to say she would, in her own funky way, but I can’t because I’m not sure I believe it and in any case I’m too afraid. I don’t want to risk this. So I smile and squeeze her shoulder and then she is gone.

Rob and I clean up the kitchen, watch some TV. We don’t talk about it by silent, mutual agreement, maybe because it feels so new, so fragile. Words will poke holes in possibility; they will breathe life into our fears.

That night in bed, in the dark, we lie there side by side, our minds spinning, saying nothing. I want to touch Rob; I want him to roll over and pull me against him, make me feel safe. I want to banish the memory of our argument before Alex arrived, the disapproval and suspicion I saw in his face.

“I can’t believe this is happening,” he finally says, and his voice is full of both wonder and fear.

“Me neither.”

We’re both silent, just breathing, and then Rob says, “I think we should see a lawyer.”

I’m shocked; it’s not like him to think that way. I’m the suspicious, cynical one. “Already?”

“Just to be prepared. Informed. You know these types of private adoptions are tricky? I mean, I looked up on the Internet and they’re not even legal in every state. And there’s a lot of laws regulating everything, even how much money we spend.”

“I know that.” I’ve spent a fair amount of time online myself.

“Alex could change her mind even after the baby is born, like a month after, and she’d be within her legal rights.”

“I know that, Rob.” My voice is sharp. “Look, you sound like you know everything, so why do we need to see a lawyer?”

“Because reading a couple of articles on the Internet isn’t the same thing as getting advice from a professional.”

“But there’s no advice for now, because you don’t actually sign any papers until after the baby is born. Most people don’t even approach a potential birth mother until much closer to the due date.”

“I know that,” he says, “but it might help to speak to someone who’s familiar with these kinds of situations, who can advise us on how to act now.” He takes a deep breath and lets it out slowly. “I don’t want to fuck this up, Martha.”

“I thought you didn’t care whether we had kids,” I retort, before I can think better of it, and Rob turns to me in the dark.

“I didn’t think I did. I never let myself hope. But now there’s an actual possibility that in eight months we could be holding our child…” I hear the optimism in his voice, but, instead of making me happy that he wants this as much as I do, it fills me with panic and fear. If Rob wants this as much as I do, the stakes are so much higher.

Now, if we lose out on this baby, Rob will be hurt too. And I have a horrible feeling that, just like with the IVF, it will be my fault.

In the end I agree to see a lawyer, and we go to her office in midtown one day during our lunch hour. Her name is Rebecca Stein and she’s tall and spare and sharply dressed, clearly my kind of woman, and yet I don’t like her.

“These kinds of adoption agreements between friends can be complex,” she says, which is no more than what Rob has said, what I know, but I still don’t like her saying it. “To be perfectly frank, it would be far easier on all parties if you arranged a private adoption through an agency or even an advertisement and conducted everything through a lawyer.”

Yes, I know that. I’ve seen the ads in the back of the free newspapers, I’ve watched Juno. I know there are thousands of desperate couples who will pay women to give them their babies, and that even if we put an ad in tomorrow we might never get picked. Alex is already pregnant, already willing. I could be holding my child in less than eight months.

“We’re committed to this particular situation,” I say and Rebecca Stein nods.

“Then you need to think very carefully about your relationship with the biological mother, and be very clear in the paperwork about what kind of relationship she will have with the child after he or she is born. I’m afraid I’ve seen these types of situations ruin a friendship all too often. And more than a friendship,” she finishes, her voice heavy with emphasis. A marriage. A life. Many lives.

I sit back in the chair. Am I willing to risk my friendship with Alex, for the sake of this child? And, to my shame, the answer is obvious, easy. Yes. Yes, I am.

Rebecca talks about the paperwork we’ll have to fill out closer to the time, the pre-certification, fingerprint records, child abuse checks, home study, all of it, but I tune it out. I am thinking about what she said.

What place will Alex have in our lives after the baby is born? Will this be an open adoption, so our child knows Alex was her birth mother? Have some kind of relationship with her? I reject that idea instinctively; it’s too…communal. But what’s the alternative? We all keep this huge secret, and it spills out eventually, awful and ugly? Or Alex just tiptoes quietly away and never bothers any of us again? How could that even happen, considering how our families are friends? How will we explain to our parents?

Rob touches my arm. “We should go.”

It’s ten minutes past the end of my lunch hour, and I have a meeting in fifteen minutes. An important meeting. I walk out of the office and into the sunshine in a daze. I am reeling from all the questions I don’t have answers to.

A couple of days later I phone Alex and ask her if she wants to meet for coffee. We haven’t spoken since she came to our apartment; Rob and I wanted to give her some space. She agrees, and we meet at a cute little café in the East Village. It is nearly the end of August but amazingly it doesn’t feel muggy or hot; everything feels clean, the sidewalks hosed down, the air fresh. We sit outside, and I drink coffee and Alex sips orange juice.

“How are you?” I ask. “How are you feeling?” She looks terrible.

She shrugs. “I’ve been better. This morning sickness thing pretty much sucks.”

“I’m sure.” I pause, wondering how much advice to offer. But then I think how I’ve always offered her advice; that’s been my role. It shouldn’t change now just because of this. I shouldn’t change at all. “I’ve heard protein in the mornings helps. A fried egg or bacon or something.”

Alex makes a face, as if to say gross, and shakes her head.

“Or eating lots of little meals all throughout the day,” I continue. I know all about being pregnant, even though I’ve never been. And never will be. “Never letting your stomach get completely empty.”

“Right.”

I can’t tell anything from her tone, whether she’s annoyed or not, and after just ten minutes I’m tired of feeling like I have to tiptoe. “Alex, you know I’m so excited about this, and I want to be involved in your pregnancy, but if I’m being too pushy just tell me to back off, okay?” I smile, trying not to feel so tentative, and Alex shakes her head.

“Martha, of course I want you to be involved in my pregnancy. We’re friends, after all.”

I take a breath. “Well, in that case, can I recommend a great OB? She was the one I was going to use, you know, if…” If IVF had worked. If I were pregnant instead of Alex. I swallow, smile. “She’s really good.”

“I’m sure she is.”

There is something hesitant, almost repressive about Alex’s tone, and I start to feel on edge again. There are going to be so many of these conversations, and I know we need to work through them. “What is it?” I ask and she sighs.

“Martha, you know I don’t have health insurance.”

“Dr. Cohen doesn’t take health insurance.” A lot of in-demand OBs don’t. You pay out of pocket and claim it back from your insurance company afterwards. Only in a place like New York could this happen.

Alex shakes her head. “And how much does she cost?”

I stare at her for a second, trying to figure out why it matters. Then it hits me. “Alex, I told you that Rob and I will pay your medical costs.”

She bites her lip, looks down. “Right.”

And I am wondering how she has forgotten this. I pause, feel my way through the words. “I mean, of course we would. It’s expected in these situations.” She nods, and I tense. “That’s okay with you, isn’t it?”

She looks up and her expression veils. “Yes, of course. Of course. I’m grateful.”

“You don’t need to be grateful. I mean, I’’m grateful. Rob’s grateful.”

A smile flickers across her face. “So everybody’s grateful.”

“Great.” I smile back, and even though I think we’ve both relaxed a little it still feels a bit too much like a truce. Already I miss our friendship, the jokey ease Alex always had with me. “So I’ll give you the OB’s number?” I finally say, and she nods. “What were you thinking you’d do, I mean, otherwise?” I’m just curious, honestly, because I mean, really? What…?

“I qualify for free prenatal services,” she says quietly. “My income is that low, amazingly enough. There’s a clinic in Brooklyn.”

A clinic in Brooklyn? I try, I really do, to keep my face neutral. Expressionless. Because inside I’m appalled. I’m horrified. I don’t want Alex going to some welfare clinic in Brooklyn. I don’t want my baby going there.

I swallow, say nothing, because with every second that passes between us I am realizing just how hard this is going to be.

Chapter 8

ALEX

I’m doing that not-thinking thing again. After I met with Rob and Martha at their place, I felt a huge wave of relief, followed by an almost unbearable wave of grief. I knew I was making them happy, which made me feel happy. Sort of. But I also felt as if I was losing something, even if it was my choice. I told myself it was natural to feel some sadness; this was a big deal. I touched my still-flat stomach and told myself to start thinking of this little bean inside me as Martha’s baby, Martha’s child.

The thought hurt.

In any case, the next few days I didn’t have time or energy to think much because I was feeling so sick, and work was crazy both at the café and the community center. We always run a week-long day camp at the end of August, and Julia gives me the week off at the Sunflower so I can be involved. Before all this happened I was excited about it. I always like the summer camps. Now I’m wondering how I’m going to make it through an eight-hour day without barfing or collapsing from exhaustion.

And all the while, at the back of my brain, I’m composing a to-do list Martha style. Buy prenatal vitamins. Call the OB. Think about everything, because I know there will be more conversational minefields about how everything is going to work, and I need to be prepared; I need to get myself into a mental place where I can handle all this stuff without freaking out or wanting to burst into tears.

Except I don’t want to think.

The first day of camp is absolutely sweltering, one of those end-of-summer heatwaves, and the gym where we register the campers is airless and teeming with kids. Jim, the director of the camp, puts me on the welcoming committee by the door, and one little kid comes in holding his big brother’s hand, about five years old and scared shitless. He stops in the doorway, pulls on his brother’s hand as if he’s trying to make him take him back outside.

“Hey there.” I smile and crouch down so I’m eye-level. He’s got the most amazing eyes, huge and dark with long, lush eyelashes. His eyes are glassy with unshed tears. “What’s your name?” I ask. He doesn’t answer and his brother prompts him with a little push on his back.

“Ramon,” he whispers, and I widen my smile.

“Hey, Ramon, I’m Alex. I run the art department. Do you like to paint? Or draw?” He stares at me uncertainly, and I wonder if he’s ever had the opportunity. A lot of the kids who come through these doors haven’t; I love introducing them to paint and clay, freshly sharpened pencils and crisp, thick white paper. It’s like candy to them, or magic.

“Ramon,” his older brother prompts, exasperated, and silently he shakes his head.

“Well, you can try both with me,” I tell him. “Whatever you like. We have clay too, and a kiln.” He’s wide-eyed and I know he probably doesn’t know what a kiln is, but it doesn’t really matter. It’s about possibility.

I smile at the big brother and as I stand up they go past me, to the registration table, and something in me tugs hard at the sight of Ramon’s little hand encased in his big brother’s, that tie of family. It makes me feel as if I’m missing out on something, as if I’m lonely.

I push the feeling away and go to greet some other kids.

The day ends at four o’clock, and I smile at Ramon as he runs towards his big brother. I noticed how quiet he was all day, how shy. During the art period I gave him a big piece of blank white paper and a tub of crayons and he just stared at me, as if he didn’t know what he was supposed to do. Then he watched the other kids going crazy with the colors, scribbling and doodling everywhere, and he spent the last fifteen minutes of class very carefully drawing a rainbow.

I sat next to him, giving encouragement, and his shy smile cracked open my heart. I can’t believe how emotional I’m being. I like working with kids, but I also like leaving them at the end of an afternoon. I like being a teacher, not a mom, being invested enough but not too much, but something about Ramon’s quiet shyness makes me protective. Or maybe it’s just the pregnancy hormones, making me see every kid here as someone’s child, someone’s person to love.

It’s close to five by the time we’ve cleaned and locked up, and as I walk outside I realize I have no plans. I haven’t told any of my friends about my pregnancy, and yet I don’t have the strength to hang out with them and pretend life is normal. I could call Martha, but that would be more of a negotiation than a conversation at this point, and just the thought exhausts me.

I stop outside my building, everything in me resisting climbing those steep stairs and sitting in my hot, cramped studio alone for the rest of this glorious summer evening.

I turn around and start to walk back towards the community center, although I know it will be locked up, empty. I suddenly feel the barrenness of my life, wandering the streets of the Lower East Side alone, nowhere to go, nowhere to be. No one to talk to.

I’m used to being alone; I usually like it. I’ve always thought of myself as independent, secure in my singleness, a free spirit. Now I just feel the absence of real relationships in my life, a loneliness I never felt before. I never let myself feel it.

I’m walking down Avenue A but at St Mark’s Place I turn west and start walking across past all the funky clothes shops and tattoo parlors interspersed every so often with the ever-present Starbucks. At Third Avenue I start walking south again until I hit Fourth Street and I’m in front of the Sunflower. It’s busy with customers waiting for their skinny lattes and chai teas, the door propped open to the still, hot air.

I’m not even sure why I’m here, until Eduardo suddenly appears from the alleyway that leads to the back entrance. He’s wearing a white tank top and cargo shorts, a backpack hooked over one shoulder. He stops when he sees me, eyebrows raised.

“Alex?”

“Hey.” I try to smile, although I’m still not sure why I’m here, or why I’m so very glad to see him.

“What’s up?”

“Nothing, really. I just…” I stop, swallow. I’m trying to remind myself that I don’t actually know this man very well. We’re work colleagues, yes, and we’ve joked behind the counter and I’ve seen him dance and we did have that one semi-intense conversation when I told him I was pregnant but added up that’s not all that much. He shouldn’t be my go-to guy, the person I need when I’m feeling lonely or lost, but the truth is I don’t have anyone like that in my life. I just didn’t realize it until now.

Eduardo hitches his backpack higher on his shoulder. “You hungry?” he asks. “You want to grab a bite?”

And it seems like the most wonderful offer in the world. I nod, too desperate and relieved to feel pathetic. “Yeah, that would be great.”

We go to Veselka’s on Tenth and Second Avenue, the Ukrainian diner that is a fixture of the East Village and has the best pierogis in the world.

“So,” Eduardo says as he bites into his huge burger and I slather my pierogis with sour cream. “Have you decided what you’re going to do?”

I don’t pretend not to get what he’s asking. “I’m not having an abortion,” I say quietly, and he nods in what feels like approval, or maybe just acceptance. For some reason I don’t say any more. I don’t tell him about the adoption or Martha; I don’t want to go into all that right now. Instead I take a bite of pierogi and ask him about his dance rehearsal. For a few hours, a single evening, I don’t want to be this sad pregnant woman whose life feels like a jumbled mess. I just want to be a woman in Manhattan enjoying the company of a guy friend who happens to be incredibly attractive.

And maybe Eduardo gets that, because he starts telling me about his rehearsal and neither of us mentions pregnancy again.

Chapter 9

MARTHA

I don’t call Alex for a week. I think about it all the time, and twice I start to scroll through my contacts to call her number before I stop myself. I am not going to micromanage her. It’s going to be awkward enough without me seeming like I’m checking up on her all the time. I know that, but it feels weird—abnormal, somehow—not to call her. We’re friends, after all. Admittedly, we only saw each other every couple of weeks if that, but not calling her now isn’t just about being busy or forgetting; it’s a choice.