Полная версия

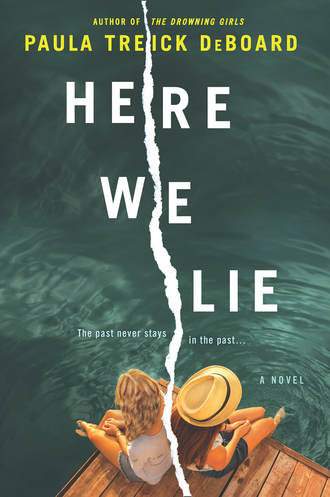

Here We Lie

“What’s your dorm?” Joe asked.

“Stanton.” I’d read the housing form so many times that I’d memorized the details by heart. Stanton Hall, room 323 South. Roommate, Ariana Kramer.

Joe circled a row of buildings and pulled into a parking lot that was mostly empty. He nodded his head in the direction of a brick monolith, patches of ivy creeping up its sides. “That’s it, then.”

I unbuckled my seat belt and it zipped back to its holster. “Thanks for the ride. I really appreciate it.”

“Hold on,” he said, shifting the car into Park. He popped the trunk and met me there, hoisting both of my bags over his shoulders with an exaggerated groan.

“I can at least carry one,” I protested.

“You ordered the deluxe service, right? This is the deluxe service.” He staggered next to me like a pack mule. At the door to Stanton, he set the bags on the ground and held out a hand, palm up. “So. Five dollars.”

“Oh.” I blinked and felt around in my pocket.

He laughed, shaking his head. “Just kidding. The first ride is free. Maybe someday we’ll run into each other in town and you’ll buy me a cup of coffee or something.”

“Absolutely.”

He turned, waving over his shoulder.

“Hey,” I called. “You ended up not being a creep after all.”

He put a hand to his heart. “I’m flattered, Midwest. A bit disappointed in myself, but flattered.”

I’d only managed to drag one bag inside the dorm when I heard his car start, followed by the rattle of his tailpipe, which grew fainter and fainter until it became part of the night.

* * *

Five minutes later, I’d retrieved a key from the resident advisor on duty and wrestled my bags into the elevator and down a long hall, past dozens of closed doors. My roommate hadn’t checked in yet, and two neatly arranged sets of furniture greeted me—beds, dressers and desks, industrial and plain. I was too exhausted to change clothes or find my bedding, so I collapsed onto one of the bare mattresses still wearing my tennis shoes.

You did it, I thought, grinning in the dark. You made it. You’re here.

For the first time in hours, I thought about my dad. I didn’t know if I believed in angels that could look down from heaven or karma or anything beyond this very moment. But right then, I thought he would be happy for me.

Lauren

The summer after I graduated from Reardon, I spent ten lazy weeks on The Island, our five acres in the Atlantic, not far from Yarmouth. The land had been in the Holmes family for generations, passed down to Mom as the last standard-bearer of the name. With nothing expected of me, I slept in until eleven, dozed in the hammock in the afternoons, avoided my mother except at mealtimes, and took late-night smoke breaks with MK in the old gazebo, perched on the east cliff of The Island.

“I wish I could just disappear,” I told MK, staring out at the water, the cigarette turning to ash in my hand.

He narrowed his eyes, giving me a faux push, as if it might send me not only toppling over the edge of the gazebo but out to the Atlantic itself, to the blue-green forever that waited beyond the rocky edge of The Island.

“Very funny,” I told him.

He stubbed out his cigarette and flicked the butt, which bounced on the railing and disappeared into the vegetation below. There were thousands of cigarette butts there by now, the accumulation of our idle summers. “Poor kid, condemned to a life of luxury.”

I tapped off an inch of ash, watching it crumble before it hit the ground. “Easy for you to say. You’re doing what you want to do.”

MK shrugged. He was starting law school at Princeton in the fall, following in Dad’s footsteps. The only difference was that he didn’t seem to mind that his life had been planned out for him, the way I did. “Well, what do you want to do?”

I shrugged.

“There must be something you’re half-good at,” he said, knocking his shoulder into mine in a way that suggested he was joking.

“Nope.”

He was quiet for a minute, as if he were trying to dredge up some hidden skill I didn’t know I possessed. Eventually, he said, “You used to draw people’s faces all the time. Remember? It made Mom furious. Instead of taking notes in class, you would basically just doodle.”

I laughed. “I could be a professional doodler.”

“Artist, dummy.” He patted me on the shoulder. “Don’t worry. You’ll get the lingo down.”

Except I knew that the little faces I drew really weren’t more than doodles, and certainly not the sign of artistic talent. I’d taken a drawing class at Reardon, and the instructor had been less than enthusiastic about my work. The proportions were all wrong, she said—the necks too skinny, the shoulders too broad. At The Coop, I’d watched Marcus capture the essence of a person with a few brushstrokes, not needing to pencil in first or leave room for erasure. I might have liked doodling, but it clearly wasn’t a skill that was going to get me anywhere.

Every day on The Island, I’d read the classifieds in the Boston Globe, scanning for options: education, engineering, medicine, social work—anything to get me away from the predicted Mabrey track. I didn’t even meet the qualifications to be a night clerk at the 7-Eleven, which required previous cashier experience. I’d entertained briefly the idea of the Peace Corps—a lifestyle that would have suited me for about five seconds—but there was a surprisingly long list of requirements, none of which I met. It turned out no one was looking for a spoiled eighteen-year-old with an unimpressive GPA.

Finally, I gave in.

It was easier to accept that I was nothing more than a cog in a machine that had been set in motion long before I was born.

* * *

Keale College in northwest Connecticut was the perfect choice from my mother’s viewpoint—far enough away that we wouldn’t bump into each other, but close enough to keep me under her thumb. Since it was an all-girls school, she must have figured I was less likely to become romantically involved with the resident pot dealer. She filled out my application, requested housing, registered me for classes and signed my name to everything: Lauren E. Mabrey. It amazed me to think of the strings she must have pulled to get me into Keale with my dismal grades and my spotty list of extracurricular activities. Had she begged administrators, promised to endow a scholarship or fund a new wing at the library? Or had the Mabrey name—as in Charles Mabrey, freshman senator from the great state of Connecticut and already something of a dynamo on Capitol Hill—done all the talking?

Mom drove me to campus at the end of August, the trunk of her Mercedes stuffed with the accoutrements for my dorm room: a new duvet, two sets of Egyptian cotton sheets, down pillows, thick blankets in zippered plastic bags. We were silent for most of the trip, the two hours stretching painfully between us. Mom’s face was stony behind her Jackie-O getup, the dark glasses and headscarf she wore whenever she was at the wheel of her car, as if to announce that she was someone, even if she wasn’t instantly recognizable. In the passenger seat, I closed my eyes against a pulsing headache and waited for the inevitable lecture, the Mabrey rite of passage, delivered on momentous occasions, like when I’d first gone away to summer camp, and every fall when I left for Reardon. Since my disaster at The Coop, her warnings were no longer vague but specific, centered on staying away from “certain kinds of people” and promising to yank me out of school if she caught so much as a whiff of pot. She wouldn’t have believed me if I told her I’d sworn off all that, that I wasn’t planning to get into any kind of trouble she would need to rescue me from, that I’d learned my lesson.

It wasn’t until we were in Scofield itself, just a few miles from Keale, that Mom cleared her throat. I waited, steeling myself.

“Your father and I disagree on certain things,” she began. “He’s willing to give you more chances, Lauren. He’s willing to excuse what you’ve done, saying you’re young and you’re still learning. He thinks we might have made some mistakes ourselves, taken our eye off the ball.” Her eyes were dark shadows behind her lenses. “But not me. I don’t agree with him, not for a second.”

I looked from her face with its slightly raised jaw to her white-knuckled hands on the wheel, a two-carat diamond winking in the sunlight.

“As far as I can tell, we’ve given you plenty of opportunities, and you’ve squandered all of them. You’ve had chance after chance to do anything, one single thing, to make us proud. But even when you were under our noses, you were involved in unspeakable things—”

Speak them, I thought, like a dare. Say his name, the one we promised never to say.

“—and we had to scramble to cover for you, in the midst of all the stress of the campaign. But I won’t do that again. I’m ready to cut you loose. The first time you get in any kind of trouble at Keale, I’m going to say, ‘Too bad, so sad,’ and let you figure it out on your own. What happens if you burn through all the money in your bank account? Too bad! What if you get caught for drinking and doing drugs because you haven’t learned your lesson? So sad! I’ll tell the officer to let you sit in jail until you figure it out on your own.”

I closed my eyes, as if I could ward off her words. I wondered if she really believed them, or if she had already come to accept that Dad’s career would always be paramount, the mountain that would bury all our sins.

“Can you at least nod to let me know you understand?”

“Mom,” I said, “I’m not going to—”

She waved a hand, like she was swatting away a fly. “Or you could choose to see this as a fresh start, a chance to fall in line. And if you do that, of course, there will be rewards. There are benefits to being in a family like ours.”

The laugh escaped my mouth before I could stop it. If MK had been here, we would have quoted lines from The Godfather to each other and talked about family with a capital F.

Mom’s voice was icy. “You’ll make your bed, Lauren, and you’ll lie in it. And maybe then you’ll see what it’s like to be cut off from all of this.”

We were heading out of Scofield by this time, in stop-and-go traffic on the tiny main street. I made eye contact with a little girl on the sidewalk holding a balloon in her chubby fist. Don’t let go, I thought.

“Lauren!” Mom snapped. “Are you listening to me?”

Behind us a car honked, and Mom pressed on the gas. The Mercedes jerked forward, only to come to a halting stop again a few feet later. I focused on what was outside the car—the hair salons and antique stores, a building with a giant tacky ice cream cone pointing toward the sky.

I already hated Scofield.

* * *

By the time we arrived on campus, Mom was back in loving mom/senator’s wife mode, schmoozing with the other incoming freshmen and their parents, shaking hands and commiserating about “our babies going off to school,” like she hadn’t rushed to ship me off to Reardon each fall and to sleepaway camp each summer. A few Keale upperclassmen were on hand to help lug things from the parking lot to the elevator bank, and Mom asked them polite questions about their hometowns and majors. “Oh, let me help you,” she said, holding the elevator for a harried-looking woman carrying a giant plastic bed in a bag. And then she held out her hand, introducing herself in her full, hyphenated glory.

“Elizabeth Holmes-Mabrey,” one of the upperclassmen repeated as we stepped out of the elevator. “Isn’t that—” The question was cut off by the doors closing, and by the time I caught up with her, Mom was already halfway down the hall, pushing open the door of room 207.

There were already two women in the room, wrestling with the corners of a fitted sheet. From the doorway, it was difficult to determine which was my roommate and which was her mother—they were both tall and slim in jeans and saltwater sandals, blond hair spilling to the middle of their backs.

I dropped my bags on the other twin bed and said, “Hi, I’m Lauren.”

One of the women stepped forward, holding out a hand with a perfect French manicure. Up close she was clearly the younger of the two, wearing only slightly less makeup than her mother. “I’m Erin.”

“Oh, goodness,” Erin’s mom gushed, clasping her hands together nervously. “I know who you are. I voted for your husband in the last election. Carole Nicholson.”

Mom beamed. “Oh, that’s wonderful. It’s so nice to meet you, Carole.”

The four of us bustled around each other, unpacking boxes and trying to navigate a space designed for two. Then Carole Nicholson let out a squeal and clapped her hands. “Oh, look, you two have the same sheets! Those are from Garnet Hill, aren’t they? The flannel ones?”

Mom looked back and forth between Erin and me, as if we’d pulled off a noteworthy accomplishment. “Well, this couldn’t have worked out better.”

“We’re practically twins,” I said drily.

When Mom stepped around me to begin organizing my toiletries, the heel of her sandal ground into my instep as a warning.

* * *

That night Erin chattered away in her bed about her boyfriend back home and how amazing it was to meet all these other girls, and my thoughts drifted to Marcus, who had been dead for almost a year. If he had lived, we would have broken up at the end of that summer and gone on to the rest of our lives. If he’d lived, he would have finished the mural and gone on to other projects, other dreams. Instead, I was here, and I had no dreams at all.

Erin’s questions interrupted my thoughts. “Were you a good student in high school? Did you have straight A’s and everything?”

“I did okay.”

She laughed. “I bet you’re just being modest, and you were like class valedictorian or something.”

“I wasn’t a valedictorian,” I assured her. It occurred to me that the Keale girls had probably all been at the tops of their classes, the sort of motivated girls who took seven classes a semester, played two sports and one musical instrument and spoke conversational French. Basically, they were just younger versions of my sister, Kat.

“Don’t you think it’s exciting?” Erin gushed, and I realized that I had no idea what she was asking, or what was supposed to be so exciting.

“I guess,” I said. From her silence, I knew it was the wrong answer.

“Maybe it’s not so exciting for someone like you,” Erin said, and she snapped out the light.

* * *

The day before the semester was scheduled to begin, I made an appointment with the registrar. Mom had scheduled me for five general education classes, and there wasn’t a single one that interested me.

“My parents are concerned about my class load,” I told Dr. Hansen, who had a severe white bob and owlish eyes behind her oversize frames. I leaned close to her desk, keeping my voice conspiratorial. “I was hospitalized for stress last fall.”

Dr. Hansen raised an untrimmed eyebrow, frowning at her computer screen. “There was no mention of a hospitalization due to stress,” she murmured, tapping keys.

“No, there wouldn’t be. My parents were trying to protect me, I think. They probably said it was mono or something.”

“Ah,” Dr. Hansen said, nodding. “Well, of course it’s best for you to talk with your academic advisor, but—”

“Oh, I’ll absolutely do that. But for now, with classes starting tomorrow...”

Dr. Hansen said, “Right. Well, let me pull up your schedule and see what we can do.”

After a bit of searching and waiting for the appropriate screens to load, she agreed that with my medical history, it might be best to drop Biology for now, and switch my math class for Introduction to the Arts. Half an hour later, I left her office feeling decidedly better about life.

* * *

Intro to the Arts was taught by a team of professors, each quirkier than the last: a visual artist, a theater director and a musician. The goal was to spend five weeks studying in each discipline and finish the semester with a portfolio of critical and creative work. I completed a shaky landscape sketch and a self-portrait that looked more like the face of a distant cousin before attending a presentation on basic photography skills. Fill the frame. Align by the rule of thirds. Look for symmetry. I watched pictures flash by on the giant screen at the front of the room, subjects so close that I could see the crackly texture of leaves, the blood vessels in a woman’s eyes. Afterward, on a whim, I wandered up to the front of the lecture hall where Dr. Mittel was packing up his equipment.

“Hi, I’m Lauren. I’m in this lecture,” I began.

“Dr. Mittel,” he said, his lower lip almost lost in an enormous beard. “But I imagine you know that.”

I looked down at the table, where a binder was open to a page of detailed notes. I wasn’t used to chatting with instructors eye-to-eye; I had never been the kind of student who was distinguished for academics, admirable work ethic or even, for that matter, decent attendance. “I was just wondering. You mentioned there was a darkroom on campus.”

“Ah,” he said. “Are you a photographer?”

“No. I mean—I’m interested, though.”

He gave me a quick glance before closing the binder and zipping up his bag. “Do you have a camera?”

“Not a very good one,” I acknowledged. Most summers, when I’d gone off to camp, Mom had sent me along with a cheap point-and-click camera and several rolls of film with the understanding that neither might survive the summer. Somewhere, in my jumble of unpacked belongings, I had a 35mm Kodak.

“Tell you what,” Dr. Mittel said. “Why don’t you shoot a roll or two and bring it by my office? I’d be happy to develop your film and look at it with you.”

“Is there something...” I hesitated, afraid the question would be stupid. Knowing it was. “I mean, in terms of a subject, is there something I should focus on?”

Dr. Mittel’s smile was kind, and behind it I read a sort of mitigated pity. Poor little rich girl, trying hard for that A. “Shoot what speaks to you,” he said. “People, scenery, whatever.”

* * *

That weekend, I rode the shuttle into town and bartered with the owner of an electronics repair store over a forty-year-old Leica, all but draining my bank account.

Erin whistled later, finding the receipt I’d placed on my desk. “You spent nine hundred dollars on that thing?”

“The owner said it was the best,” I told her. The camera and its accessories were spread out on the bed, and I was figuring out the lenses and attachments from the store owner’s scribbled notes. The Leica came with a somewhat battered case that I instantly loved, thinking of all the places it must have gone with its previous owner.

“But this is just for one assignment, right?” she asked. I could see her mind clicking like a cash register. She would tell her friends, all the other Keale girls who were just like her, and I would be an anecdote to their stories, an inside joke. The girl who tried to buy her way to an A.

“For now, but I might take a photography class next semester,” I said, the idea just occurring to me.

Erin frowned. “Isn’t everything supposed to be switching to digital?”

I raised the camera to my eye, locating Erin’s perfect, pouty face in the viewfinder. She raised a hand in protest, and I snapped a picture, relishing the smart click of the shutter, the dark curtain spilling over the lens.

“Lauren! I don’t even have my hair done.”

“Relax,” I said. “It’s not loaded.”

I spent the next week shooting rolls of film all over campus, looking for interesting angles and tricks of light. I lugged my camera bag to the chapel to shoot the sunrise streaming through stained glass, and onto the roof of Stanton Hall at sunset to catch the last wink of sun as it disappeared over a row of elms, the branches backlit. I stopped some girls on the way to class, and photographed them with their arms around each other’s shoulders. “Is this for the yearbook?” one of them wanted to know, and I told her it just might be. What I liked most was the feeling of authority that came with the camera hanging from my neck, and the way I could instantly disappear when I looked through the viewfinder.

Dr. Mittel developed two rolls for me and we met in his office to look at the contact sheet through his loupe, a cylindrical magnifying lens that he kept on his desk. He passed over the smiling girls in their stiff poses, the sunrises and sunsets. “This is good for a first attempt,” he said finally. “You’re looking for all the right things—angles, lighting. And you must have a good lens on that camera of yours.”

I told him about the Leica, my splurge, and he frowned, either at the expense or at the thought of some no-talent hack having access to such nice equipment.

“I assume you’re serious about this, then,” he said, passing me the contact sheet. “The best thing for you, I think, would be to take a class this spring. I teach an intro course—very hands-on, lots of time in the darkroom, some developing techniques—”

“I’ll look into it,” I said, my heart hammering. Suddenly it was imperative that I take that class.

“As far as your portfolio is concerned, I think you probably already have a few prints here you could work with. But we’ve got some time, and you could certainly keep going. I feel like you’ve shot the things you think I wanted you to shoot—maybe the things you thought you should shoot. I’d like to see what you’re interested in. What does Lauren find fascinating?”

Over the next two weeks, I shot a half dozen rolls of film, trying to let Dr. Mittel’s words sink in. What did I find fascinating? I shot the empty girls’ bathroom, with its rows of gleaming sinks, the jumble of shoes in the bottom of my closet, the third floor of the library, the shadows of the shelves creeping across the carpet. I shot tree branches and leaves, a lone red-breasted bird perched on a fence. Shoot what you want to shoot, not what you want me to see.

And then one morning, I looked over at Erin, sleeping, lovely Erin, who was just like all the girls I’d ever known. She had a boyfriend at Boston University, and during her nightly chatter, I learned that she had planned their lives down to the most specific detail—engagement after their junior year, the wedding after graduation, kids two years apart. During the daytime, she looked too calculated, too poised, her face hidden behind foundation and powder, blush and mascara, the pinkish lipstick she reapplied even when it was only the two of us and her grand plans for the evening included sending an email to her boyfriend.

But at that moment, with the sunlight filtered through our Venetian blinds, creating light and dark panes on her face, she was a different Erin entirely. Pale wisps of hair covered one cheek, and her mouth was slightly, sweetly slack, with the tiniest bulge of fat beneath her chin. Beneath her pale yellow pajama top, the hard knot of one nipple was visible.

Before I knew what I was doing, I was freeing my camera from its safe spot at the top of my closet. I snapped one picture, and then, moving closer, another. In this moment, Erin was lovely in a way she’d never been before—relaxed, vulnerable. A small red blemish on her chin was visible; her lashes were pale and fragile against her eye socket. I knelt next to the bed, snapping away, entranced.

“What are you doing?” she murmured, drawing a hand over her face.

“Sorry. Just checking something on my camera,” I said, letting it hang loose from the strap around my neck. “I was going to head out to take some pictures...”

“It’s so early,” she moaned, rolling over, pulling her Garnet Hill sheets and the matching comforter into a heap over her head.

I was aware that it was creepy, that photographing a person without her knowledge was crossing a definite line. But I’d captured something good in that fleeting minute, which made me understand something else: none of the pictures I’d taken before—the landscapes and sunsets and reflections off buildings, the stained glass in the chapel—were any good. These ones were.

By this point, after a few weeks of tailing Dr. Mittel, I’d picked up the basics in the darkroom and he usually let me operate more or less on my own, only popping in occasionally to look at my negatives. It was a thrill to see Erin’s face appear during the developing process, the sunlight catching the fine strands of hair, the wet corner of her mouth. I stared at her face in the stop bath, warmth spreading through my body. I’d created this. No—that wasn’t quite right. It was simply there, but I was the one who found it. Afterward, I held my breath while I waited for Dr. Mittel’s regular verbal cues—the harrumph and hmmm, the tapping of his finger against an image. Instead, he was silent.