Полная версия

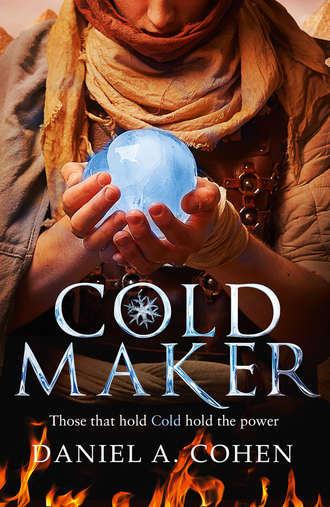

Coldmaker: Those who control Cold hold the power

I raised my head, fear stiffening the rest of my body. However, his eyes were soft, and he gave me a conspiratorial smile.

‘Arms up,’ he said.

I did as he commanded, hoping he would take it easy on me.

‘Spin.’

I turned around and felt him tugging at my shirt, making it look as if he was fixing something. I could feel the heat of his breath as he leaned in and whispered, ‘Pretend to faint after the first hit.’

He stepped back, and then I heard the rod cut through the air, to land on my shoulder. The blow was quite strong – he had to make it look real – but the pain wasn’t anything I couldn’t handle. I doubted the bruise would be bigger than my thumb, barely even playable in Matty’s shape game. I gasped loud enough for my audience to hear, and then crumpled to the ground, not daring to move.

‘Enjoy your new fan,’ Geb said to the High Noblewoman. ‘Praise be to the Khat.’

‘That’s it?’ she asked, aghast. ‘One hit? No—’

Geb cut her off. ‘You requested until he fainted. He fainted. Praise be to the Khat. I believe we are done here.’

‘But it’s faking! It—’

‘Your words, not mine. Now please, allow me to do my job or I will be submitting a writ of complaint to Lord Suth that a member of his family is interfering with one of the Khat’s Jadanmasters, and by decree six, stanza twelve of the Khat’s law, which prohibits High Nobles from—’

The woman gave a venomous huff, and I heard her heavy feet pad away.

I kept still, trying not to breathe in too much sand from the ground as the rest of the audience dispersed to a chorus of disappointed moans. Soon enough they’d be swept up in the fervour of trading precious Cold for useless goods and forget all about me.

After a few moments, hands swept under my armpits and lifted me up. ‘Thank you, sir,’ I said, as he set me on my corner.

He gave me a firm pat on the shoulder, glaring at the three taskmasters, who were still waiting nearby, just in case. ‘Liars are not beneficial for my operations. As always, you did exemplary, Spout. Perfect shade of pink. Like I imparted, more Jadans like you, smooth as silk through fingers.’

Chapter Five

The last of the Street Jadans trickled in, and eventually the sloping right wall of the common area was completely lined. Although most of us had some sort of painful trophy to show from the day, we’d returned in one piece, another shift having survived the Sun.

At the end of the day, Jadans’ mouths were usually too thirsty for small talk, but it never usually stopped Matty from keeping my ears occupied.

‘Hey, Spout,’ he practically shouted.

‘Yeah,’ I said, trying not to move my lips too much for fear of them cracking.

He dug a finger in his ear, shifting his jaw. I wondered if his Jadanmaster had boxed his ears again. ‘Wanna play “whatsit”?’

I nodded. My mind was still racing from tinkering on the Cold Bellows, and in truth I would have loved to ponder quietly on that, but I had sworn to myself long ago that I’d do anything I could to keep Matty happy.

My friend lifted off his shirt and pointed to a series of fresh lashes on his shoulder. I winced, knowing how much they would still sting. As soon as the curfew bells rang and we were allowed off the walls, I would give him as much of the groan salve as he wanted.

‘Whatsit?’ Matty asked.

‘Hmmm.’ I traced the lines on Matty’s back, trying to come up with something good. ‘It’s the three paths that Adam the Wise took through the sands to the Southern Cry Temple.’ I touched the first path. ‘This one is where he had the vision that the Drought was coming.’ I touched the second. ‘This is the one where he found the white fig tree.’

Matty gave a thoughtful nod. ‘Pretty good. I figured it felt like that.’

I took my shirt off next, careful not to rotate my arm too much. I pointed to the bruise on my shoulder that Geb’s rod had given me. ‘Whatsit?’

Matty’s small fingers traced the outline of the bruise. ‘Dwarf camel.’

‘A camel?’ I smirked. ‘That’s all you see?’

Matty shook his head. ‘No. Course not. It’s a camel that carries the Frosts from the Patches to the Pyramid.’

I pretended to wince. ‘That’s one strong camel.’

Matty shook his head. ‘Frosts are almost as light as air.’

I raised an eyebrow. ‘How would you know? Jadans aren’t allowed to touch them.’

‘Because they don’t fall ’smuch as the other Cold,’ Matty said, as though it were obvious. ‘They prolly don’t weigh a lot since they float in the sky so long.’

I chuckled. ‘You might be onto something.’

Matty lifted his chest off the wall so he could look across me to Moussa. ‘Hey, Moussa. Whatsit. Your turn.’

Moussa looked down at his feet, keeping his eyes decidedly off the piece of front wall reserved for the Patch Jadans. ‘I don’t really feel like playing.’

‘What? You didn’t get any marks?’ Matty asked.

Moussa gave a resigned shrug. ‘A few. I just don’t want to play.’

I gave Moussa a light nudge with my elbow. He shook his head, but I countered with a look that asked him to play along. At ten years old, Matty was still young enough to find beauty in such a world, and Moussa and I both knew that sort of innocence was something worth prolonging.

Moussa sighed, lifting off his shirt in a long pull.

Matty’s face dropped. I had to hold back my grimace.

Moussa’s chest was riddled with fresh bruises. It looked as if he’d been tossed down the Khat’s Staircase. Puffy welts wrapped around both sides of his stomach, and from my limited training with Abb, I thought Moussa would have at least one cracked rib.

Jadans weren’t allowed to get off the wall, so instead I turned to the side and placed my hand gently on the back of his neck, pulling his forehead against mine. ‘Sorry, brother.’

Matty had tucked himself back against the wall, his face mortified. Moussa leaned across me so he could give Matty a weak smile, his dry lips cracking. ‘Right, I thought we were playing whatsit? So whatsit?’

I looked over all the bruises, imagining the strength that must have been behind the blows. ‘It’s a song.’

Moussa nodded gently. ‘What song?’

‘We can call it the “Jadan’s Anthem”,’ I said, hoping he’d play into it. ‘It’s about time we had one of our own.’

Matty’s face lifted, a sly grin on his lips.

Howdin, who was standing on the other side of Moussa, shot us a fierce stare. ‘Don’t blashpheme like that.’

Moussa shrugged. ‘Listen. I’ll make sure the words won’t be blasphemy. Besides’ – he nodded to the main doors—‘no one’s going to hear.’

‘The Crier will hear,’ Howdin said, his face anxious, looking at the slats in the ceiling, the Sunlight finally retreating.

‘Here’s the thing. The Crier doesn’t listen to us,’ Moussa said with a huff, prodding at his bruises. ‘Closed Ears, too.’

Matty leaned forward, looking over the bruises. ‘Whatsit sound like, Moussa? Our song?’

Moussa finally cracked a smile, pointing to the bruise above his belly button. He sang out a long note, and my ears shuddered with delight. It’d been a long time since I had heard my friend sing, and I’d missed his voice.

‘The Jadan’s work upon the sands,’ Moussa sang, hopping from bruise to bruise on his stomach. Then he stopped, his burned lips searching for the fitting words.

‘Those who need the Cold?’ I offered.

‘Those who need the Cold,’ Moussa sang softly. He seemed satisfied, and moved his finger back to the first bruise, hopping along the painful spots:

‘The Jadan’s work upon the sands

Those who need the Cold

Family forever

Older than the old

Blessed be …’

Howdin was pushing as far away from Moussa as he could, but Howdin had always been a little twitchy. The rest of the Street Jadans looked on, smiling. Considering we had to drone the ‘Khat’s Anthem’ every morning, most nearby ears seemed eager to listen to something else – so long as Moussa kept his word about staying away from blasphemy.

‘Blessed be the birds,’ Matty offered with a smile, tucking the metal feather behind his ear.

Moussa laughed, which was almost better than the music. ‘Listen. Why don’t we sing for something real?’ He thought it over and then picked up where he had left off:

‘Strength to the forgotten

Who still bleed for the lands

So maybe the World Crier

Might release their han—’

Moussa was about to move over to the bruises on his side, when the Patch Jadans burst in through the main doors. They always came together, and were always last to make it home, but Joon led them right to their wall, settling into their stances.

Moussa darkened at the sight of their leader, quickly finding interest in his own feet.

At last, everyone was home.

Old Man Gum began to wave his arms about, pointing to the chimes. The bells began to ring, our curfew officially set. We couldn’t prove it, but we all knew that Gramble took pity on the Patch Jadans and waited until they got home to ring the bell, instead of judging by his Sundial. Anyone not home in time didn’t get rations, which, considering the little we were given, was torturous.

Our Barracksmaster passed through the doors, dragging in the rations cart. He came around with the Closed Eye, and we all kneeled for our evening portion of figs and cooled water. Then everyone stepped down from their walls, parents and children sweeping together in hugs that often looked painful, limbs careful not to squeeze too tightly. Matty hovered beside Moussa and me, always looking a bit awkward when this time came. A few years back Matty had been assigned Levi as his father, and not all fathers were like Abb. Levi was a man of scowls, who often expressed his disdain at having such a ‘pathetic excuse for a Jadan’ forced upon his lineage. Moussa exchanged a cursory wave with his assigned mother, Hanni, which was the extent of the affection I ever saw them show one another.

Abb began making his way over, a broad smile on his lips, calling to us while pointing at the bells that had now finished ringing. ‘Hey, boys. Did you have a good chime today?’

I slapped my forehead.

Abb shifted around the hugging bodies. ‘Good chime? Like good time. Get it—’And then his eyes went to Moussa’s skin, his expression slipping as the bruises registered.

‘Moussa, come with me, we’ll get the healing box,’ Abb said. ‘Now.’

Moussa didn’t react, having got lost in a feverish stare. Sarra and Joon were now embracing in a lingering hug, doing their best to squish out any air left between their bodies.

Abb put a gentle hand on Moussa’s shoulder. ‘Trust me, kiddo. When it comes to broken hearts, the one with the hammer is never the one with the mortar. Now let’s get you looked at, make sure you don’t have any cracked ribs.’

Moussa nodded, knowing better than to argue with the Barracks Healer when he looked that serious.

‘What’cha sad for, Moussa?’ Matty asked with a curious tilt of his head. ‘I never even seen you talk to Sarra.’

Moussa’s hands balled into shaky fists, shooting a look of pure disdain down at Matty. ‘I was going to!’

Matty gave a single frightened jerk and then fell into his slave stance.

‘Moussa …’ Abb warned.

‘Sorry.’ Moussa sighed. ‘Family.’

Matty slowly reached out his trembling arm, tilting his wrist back.

Moussa rolled his eyes and then touched Matty’s ‘calm spot’ with his thumb.

‘We’ve got enough Nobles yelling at us,’ Abb said with a nod. ‘You boys don’t need to add to the noise.’

I gestured to Matty’s back with a stab of my forehead.

Abb leaned over and graced Matty’s injuries with a glance. ‘You too, featherbrain. Let’s get you Patched up. Get it?’

Moussa groaned, but Matty smiled.

‘Use my salve,’ I said. ‘Save your medicines, Dad.’

Abb raised an eyebrow, but I knew he’d be proud. ‘And are you going to tinker while I work, Little Builder?’

‘I’m going out,’ I said, lowering my voice so the swarming families on either side wouldn’t hear me.

Matty looked up, worried. ‘But the Procession is soon. The taskmasters are prolly going to be all over. Stay here and help me find a place for that marble nose.’

I tapped the side of my head. ‘I’m working on my own thing. Don’t worry, I’ll be careful.’

‘What are you trying to find?’ Moussa asked in the subtle tone he used when he was curious about my tinkering.

I paused. I intended to find more sheets of waxy paper tonight, which would be a vital part of the Idea; I thought if I didn’t say it out loud, maybe I could convince myself to give it up, but I knew it wasn’t only finding materials that I craved. My mind kept returning to the image of a rigid back.

‘Something different,’ I said.

I sat cross-legged on the roof, hoping the Upright Girl might finally appear out of the darkness. Most of the night had already passed, and still she had yet to show her face or braided hair.

In truth, there had been no need to come back to the Blacksmith Quarter, to the alley where the girl had watched me deny the Shiver, and I should have been back in Abb’s room, deep in sleep. With the Procession coming up, it wasn’t safe to be outside the barracks at this time of night. The taskmasters had their own quotas, and the closer it got to the ritual, the more desperate they became to fill them.

I’d been sitting in the same spot so long that my feet had fallen asleep. The light from the stars bathed the Smith Quarter in a soft glow, and in the distance I could see the last streaks of the Crying over the Patches, now swollen with Cold. I thought about my three Wisps and how they had once fallen into those same sands. A tired Patch Jadan would have picked them up and added them to his bucket. What might that Jadan think if he knew those Wisps would end up under my blanket? What might he think if he knew my Idea?

Abb would be worried by now, but I didn’t want to leave the roof yet. I had no clue what else I could do to draw the Upright Girl out. I continued to keep my back at a scandalous angle, straight and uncomfortable, hoping that it might be the key to her trust. I could have sworn I sensed her out there, in the shadows of Paphos, watching me.

A part of me thought I might just be imagining her presence, so desperate to think she was there that I was creating faces in the shadows and conjuring dark figures at the corners of my eyes. Even the Jadans plundering the rubbish heaps had gone home now, taking advantage of the last hours of darkness to get some sleep. At this point, I thought, even the taskmasters must be in their beds.

My Claw Staff waited impatiently by my side, sitting on top of the pile of waxy fabric it had dredged up, urging me to go home. I’d got what I wanted. After working on Mama Jana’s Cold Bellows, I was now riding a dangerous current of inspiration. The boilweed heaps behind the flower shops had offered me the rest of what I’d need for my next invention. Since the waxy fabric was used to protect the flowers from the Sun as they were delivered, I figured it must also be good at keeping Cold in. Now, I had the Wisps and the materials to make the Idea happen.

I needed to firm up a few new excuses on my crawl home.

In the distance, the Crying finally stopped, and even the stars began to dwindle. The night wind continued to bring in cool air. I yawned deep, enjoying a few moments of Gale’s breath, and then finally let my back settle into the crook it was used to.

I sighed. It was time to go.

I packed up my things and strapped the Claw Staff back to my thigh. Taking one final glance into the alley just in case, I began crawling the long expanse of rooftops back to my barracks. If I was lucky I’d get a few hours of sleep, enough to take the edge off.

I’d just crossed into the Garden District when I saw her.

She was lying flat on her stomach, just like I was, her body huddled on a nearby roof. I wanted to call out, but I wasn’t sure if she was lying motionless because there was a taskmaster lurking in the alley below. My heart began to pound in my chest, nervous for what I might say to her.

I crept over to her, slowly, so the waxy paper wouldn’t rustle in my boilweed bag. Shuffling up from behind, chest hammering, I noticed she looked smaller than I remembered, and her uniform was dirtier. She remained still. I picked up a few pebbles and tossed them forward so they’d land just beside her legs.

No reaction.

I couldn’t tell if she was just dismissing the stones, or if she was unconscious with heatstroke. I took a chance and lifted myself to my knees, jolting my head from side to side, but the street seemed clear as far as I could tell, so I gritted my teeth and stood up, rushing over to her body.

Then I stopped short. The body wasn’t hers.

And it was dead.

Kneeling down, I extended my Claw Staff and rolled the corpse over. The boy’s head had a long piece of boilweed slung over one eye. I recognized him as the feral prowler from last night. I had to put a hand over my mouth to stifle my choking, wondering how the few beetles crawling over his face had been able to devour so much of his remaining eye.

The boy’s limbs were stiff, the blood having pooled in the lower half of his body, and I knew there was a chance he’d been lying there for most of the night. I spun around looking for a loose brick or big chunk of stone. Finding a piece on the next rooftop, I tapped beside the body, trying to scare away anything that might sting or snap from the folds of skin.

‘Family,’ I whispered, making sure the boilweed sling was still tight around his head. Manoeuvring the eyepatch revealed something shiny and smooth tucked away in the empty socket, and I realized that’s where the boy must have hidden the items precious to him. He was an Inventor in his own right. He’d had a need and had created a solution. It was crude, and simple, and beautiful; and although I yearned to know what sort of plunder he’d been keeping in there, I thought it best to let the boy carry his secrets into the darkness.

Making sure the nearest alley was deserted, I rolled the body to the edge of the roof, stepping clear of the little brown insects. One big heave and he was in the air, a hard thud following below shortly after.

In the morning, the dead-cart Jadans would patrol the alleys, but not the rooftops. The boy deserved to rest in the sands with our other fallen kin.

There were dozens of different reasons why he might have died, all unfair, and all perfectly believable. He was born Jadan, which meant he was born in debt. A Noble had probably demanded his eye for some unintended slight, and thus doomed the boy to a very short, very desperate life of scavenging half-blind in the darkness. Anger seethed in my chest. My hands balled into fists, stopping tears that begged to be released. This boy wasn’t alive eight hundred years ago. He had nothing to do with the sins behind the Great Drought, and he didn’t deserve to reap the punishment. None of us did. But still, the Crier continued to forsake us.

Scuttling away, I touched the waxy fabric in my bag, deciding I should use the opaque material for something else. Something less offensive to the Crier. But it was hard, knowing how much needle and gut Abb had in the healing box, how easily I could stitch the body of the Idea together. How perfect it would be.

Jadans could die anywhere, and for anything. There didn’t need to be a reason. Really, I should just take the leap, considering most other paths had us ending up like the eyepatch boy anyway. The Crier hadn’t cared about my other inventions. The crank-fans went against tradition, too, alleviating some of our suffering; and I had about a dozen of those.

My fingers trembled, thinking about putting the crushing chamber of the Idea together. If the Crier didn’t like what I was planning, then He wouldn’t have let me get this far.

Perhaps His Eye genuinely was closed to the Jadan people.

Either way, my feet itched to step into the unknown.

Chapter Six

Five days later I stood on my corner, back hunched against the sizzling sky, thinking again about the three Wisps.

The Gospels told us to focus on one thing only during Procession day: the mercy of the Khat, and how he’d saved the Jadan people from extinction. Though I was supposed to reflect on the fact that I wouldn’t have any Cold without his benevolence, I couldn’t stop thinking about what I’d done.

I hadn’t been able to help myself.

While bringing the Idea to life, I’d fallen into something of a trance, my fingers moving by themselves, my mind simply following them. The tinkering had started slowly, hesitantly, but as the night went on, starlight diving through the slats to encourage my work, things began to feel right. More right than anything else I’d created.

Which was clearly wrong.

I’d finished the Cold Wrap in the early hours of the morning, everything coming together better than I could ever have hoped. The design was simple enough: I’d fashioned two layers of waxy paper into a garment that wrapped around my chest. Thanks to Abb I knew how to stitch a wound properly, and so I was able to sew the layers airtight, leaving a bit of space in between the sheets. With a small metal grate, some springs, gears, and skill, I’d tinkered together a small chamber to crush the Wisps, which I put on the side of the Wrap.

The Idea was similar to Mama Jana’s Cold Bellows, where the Wisps could be crushed throughout the day, slowly spilling the Cold; but in this case, instead of the Cold going into the air, it would filter inside the Wrap itself, meaning I could wear it under my uniform and secretly keep myself cool throughout the day.

That was the theory, at least.

I still hadn’t been able to get myself to try it out, my hands trembling each time I touched the crushing lever, but I didn’t know how much longer I might be able to refrain.

Once I used the Wrap, there was no going back. This was a blatant disregard for a Divine decree. This was blasphemy and rebellion, all rolled into one garment. The Crier had forbidden Jadans from having Cold any more for a reason. He wanted us to feel the burn of His Brother Sun for eternity. Yet, there was still no sign of his discontent.

A sheen of sweat covered my forehead just from the thought. I wanted to wipe it away, but I didn’t dare move in the presence of so many taskmasters, Priests, and Nobles.

The Procession was the most popular event in Paphos, and there were eyes everywhere. Every initial Khatday of the month, the Street Jadans were reminded of what happened to those who broke one of the first three rules.

Caught out at night: chained in the Procession.

Found with stolen property: chained in the Procession.

Off the corner without a Noble token: chained in the Procession.

Arch Road was now filling with spectators, all waiting to watch the Vicaress do her work. Some Nobles even made a full day out of it, following the Procession throughout each Quarter, stretching out the entertainment.

Finely dressed Noblewomen stood in little groups, holding their colourful display of parasols and chatting about all the pain the dirty slaves deserved. They drank flavoured water and ate orangefruit, scattering the precious peels on the road. I could smell the baking citrus, and my mouth grew even more parched. High Noblemen in gleaming white sun-shirts proudly conversed about the brutal techniques they used to keep their personal Jadans in line. A few painters sat on stools, parchments stretched over easels, ready to be inked. Brushes and quills were poised in hands, eager to capture the twisted expressions of pain.

I knew from the Domestics that High Houses paid good Cold for those images to hang on their walls. The Closed Eye was everywhere. Most Nobles displayed the symbol on a necklace, but I also saw stout-brimmed hats with the Eye woven in. Ceramic versions swung on long golden chains. Boilweed sculptures of the Eye, painstakingly glued to precision. A few waterskins, with the Eye painted on their bellies, each drink a reminder of Jadan thirst. Small children holding small cotton pillows in the shape of the Closed Eye, hugging them close, stroking their soft fabric.