Полная версия

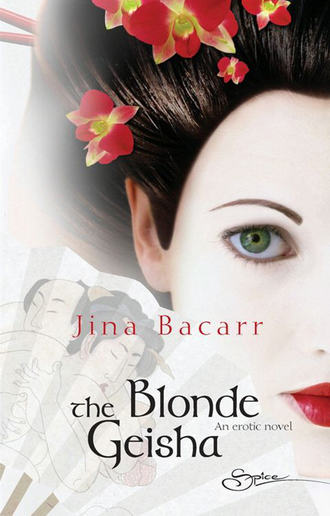

The Blonde Geisha

I opened my mouth, ready to ask Father what he was keeping from me, but the girl sitting next to me cleared her throat. I stared at the young maid as she put her finger to her lips, warning me to keep silent.

“What’s wrong?” I asked her, somewhat confused. Had I broken the geisha rules?

“I’m most sorry and beg your pardon,” the girl whispered, bowing. “I didn’t wish to offend you.”

I bowed, saying nothing. How could I have let my excitement to become a geisha make me forget my manners? The girl saved me from losing face by speaking to my father in a situation where I was supposed to remain invisible.

My actions hadn’t escaped my father’s eyes.

His stare was fixed on me, making my heart beat wildly in my chest, fluttering like a butterfly caught in a jar. He was aware of my language skills, so I wasn’t surprised when he turned back to Simouyé and said, “She knows my life is in danger.”

“Does she know you’re returning to America?” Simouyé asked, the words catching in her throat.

This time I couldn’t suppress the fear leaping into my heart as quickly as a rabbit fleeing the arrow of the hunter. This wasn’t what I’d expected to hear. I panicked.

“It’s not true, Father, is it?” I cried out, jumping to my feet, not caring if I was breaking the rules. My father was more important to me than rules. I rushed into his arms and pressed my cheek against his chest, sobbing, “You’re not going away, are you? You can’t.”

“Shouldn’t you tell her the truth?” Simouyé asked. This time her voice was stern, demanding.

“No, she’d be in greater danger if she knew,” my father answered. “She must stay here with you, Simouyé-san, and learn to be a maiko. Leaving her here is the only way I can escape from the Prince’s devils.”

The woman bowed and I could see it was with great effort when she said, “As you wish, Edward-san.”

I didn’t want to believe this was happening to me. Couldn’t.

“I want to go with you, Papa,” I blurted out without thinking, pushing aside my dream to become a geisha, my heart speaking out to my father as I grabbed on to the sleeve of his coat. He noticed my use of the endearment and it startled him. I thought he was going to change his mind. Instead, he cupped my face in his hands and looked into my eyes. I couldn’t see his face through my tears, flowing as fast and sure as the rain beating down upon the wooden teahouse, but I could hear his words.

“I must return to America, Kathlene, until I can find a way to right the wrong I’ve done.”

“You’ve done no wrong, Father. You’re good and kind.”

“I wish it were true, Kathlene, but I’ve failed you this time. And for that reason, I must go.”

“Why can’t I go with you?” I cried out, my voice carrying throughout the teahouse, inviting peeping eyes through the paper doors, listening. Young, curious girls huddled together outside the half-open sliding door, staring out at me, the blond gaijin, but I paid them no attention. Yes, I wanted to be a geisha, but my father was more important to me.

“The danger is too great, Kathlene. I must travel quickly and not always in the most pleasant surroundings. You must stay here with Simouyé-san. She’s a good woman and will treat you like a daughter,” he said. Then he finished with, “You must do what she tells you, Kathlene, even if you don’t understand why. My life depends on it.”

“Is this the only way, Father?”

“Yes. I’ve never asked anything of you, Kathlene,” my father said, deepening his voice with a dark color I hadn’t heard before, ordering me not to disobey him. “But you know the ways of this land, and the importance of filial duty.” He stroked my hair with his fingers, pushing it away from my face and forcing me to look him in the eye. “Don’t bring disgrace upon us.”

Although I was often too curious for my own good, listening to Father speaking to me in such a demanding voice frightened me. Yes, I knew how important duty was in this land. The whole society was built on loyalty to one’s family.

I had no choice but to do as my father asked, though this was a strange proposition fate had dealt me. To achieve my dream to become a geisha, I must give up the one person in the world I loved the most. My father. What unholy trick were the gods playing on me?

With a tiny rattling in my throat, and though my self-control was barely holding, I managed to speak.

“I understand,” I said, feeling the weight of numerous pairs of dark eyes riveted on me, especially the young maid who’d held me back when I wanted to rush forth with my wild emotions.

“Are you certain you know what’s expected of you, Kathlene?” Father demanded, lowering his gaze to meet my eyes.

“I’ll do as you wish, Father,” I said with reverence, not understanding why I did so. Maybe it was because I was painfully aware of the importance of the situation, or the number of black-haired young girls peeping at me, their eyes taking in my uniqueness, their voices whispering. Perhaps for the first time in my life, I was pitted against something I could neither fully understand nor successfully defy. I couldn’t deny I was intrigued with the idea of joining these young women who so openly showed their curiosity of me.

They don’t believe I’ll stay. Americans are like butterflies flitting from flower to flower, a Japanese poet once wrote, and as restless as the ocean. I must pull back my own restless feelings and wait. Wait for my father to return and wait for the day when I would become a geisha.

I let go of his coat.

My eyes blurred with tears I struggled not to let fall when my father kissed me on the cheek. Then without another word, he raced out the secret entrance of the teahouse and disappeared into the rain, into the night, into another world where I couldn’t go. The voyage back to America could take as long as eighteen days, Father had told me, the weather often cold and stormy. Although icebergs didn’t float down the shallow reaches of the Bering Strait, fierce winds blew through the gaps and passes in the Aleutian Islands and many ships were lost in the rough seas. I prayed my father’s ship wouldn’t meet such a fate.

I lifted my chin and pulled up my shoulders. It wasn’t the way of this land to show emotion in front of anyone. I forced myself to show courage and make my father proud of me.

Here at this late hour on this summer night in the Teahouse of the Look-Back Tree, I would begin my training to become a geisha. Geiko, as the geisha were called in Kioto dialect. I’d learn to be the perfect woman in an artificial world where such a woman was schooled in the erotic, her mouth sensuous, her smile winning but discreet, her eyes sparkling, ready to seduce as well as to entertain.

I’d be taught to have better manners than anyone else but to also speak my mind, to laugh inan engaging manner and to be flirtatious. Every dainty gesture—whether it be the lowering of my eyes, the tilt of my head to show the exposed back of my neck, the sway of my long fingers—would complement the meticulous stylization of my training. I’d exude the art of sexual sublimation and function as a living sculpture of the female ideal, polished to perfection.

And always, above everything else, I would make men feel good. I’d learn how to entice them with the curves of my body and bring them sexual excitement. Like a bee savoring its first taste of the nectar or a hungry bird pecking at the peach and melting the soft pulp in its mouth, so the world of pleasure would be my world, embracing me like a lost daughter.

Gathering up my curious and girlish spirit and putting it away into a secret spot in my heart until I could let it run free once more, I turned to Simouyé and bowed.

“I’m ready to begin my training to become a geisha.”

3

Snip-snip. Snip-snip.

My stomach clenched with fear. What was that noise? It sounded like scissors cutting. I tried to open my eyes to see what was going on. I couldn’t. I lay helpless, unable to move, as if I were under a spell.

Then I heard a different sound. A sigh, then another, followed by more snip-snips and a paper door sliding open. A girl’s voice asked, “What are you doing, Youki-san?”

“Cutting off her golden hair.”

My hair? Oh, no! I struggled, struggled, but I couldn’t raise my arm to protect my hair.

“Why, Youki-san? She’s so beautiful.”

“Don’t you understand, Mariko-san? She’ll ruin everything for us with her hair the color of silken gold threads.”

Ruin what? I kept trying to open my eyes, move my arms, my legs. I couldn’t. My lids weighed so heavy on my eyes while the rest of my body lay helpless like the cold, slimy fish I’d seen tossed up onto the pier when Father took me down to the wharf to meet the ships arriving from across the sea.

No matter how hard I tried, I couldn’t move. I lay on my back on a scratchy mat digging into my skin, shielded from its prickly weave by what I perceived to be a sheer kimono underrobe, its silkiness hugging my body. A cool breeze swept over my skin when someone walked near me. I heard the swish of long robes on the tatami mat and the glide of soft feet. Salty drops of perspiration wet my lips and drizzled down my chin. I let out my breath and relaxed. The girls had gone.

Where am I? What happened?

I remembered following Simouyé down a shining corridor and upstairs to a long, low room divided into three sections by screens of dull gold paper. Before she could stop me, I ran to the open balcony of polished cedar and looked out into the night, hoping to see my father. But he had vanished.

My heart ached so, I couldn’t help but sink down to my knees in front of a wall screen and claw at the delicate branches painted on it, crying. I prayed the gods wouldn’t look unkindly on my actions, but I had the strange feeling I’d never see my father again. My loss brought up so much anger in me, so much sorrow, I pushed aside everything the missionaries taught me. In my anguish, I grabbed the flower vase out of the alcove in the wall and threw it across the room to vent my fury. Simouyé stood and watched, her face showing no emotion, as was the way of the geisha. Panting, out of breath, my emotions spent, I stood there, watching her watching me. It was the most spiritual moment of my life up to that point. Strange, but that lack of emotion calmed me down, made me dry my tears.

I shivered now as the coolness played tag over my bare breasts, bringing my nipples to hardness like the buds of a cherry tree. A pleasant feeling washed over me as I began to move my fingers, then my toes. Were the gods releasing me from the sleep of dead spirits? If so, I must escape before the two girls returned. I wiggled my hips and the silk robe fell away from my belly. My entire body quivered as if I’d been touched by a probing hand. I spread the palm of my hand between my legs to cover myself and the softness of my bare skin slid under my fingers, then—

A gasp caught in my throat, pressing into my brain a truth I didn’t want to believe.

My pantaloons were gone. I was naked down there.

Where were my clothes? Yes, I remembered. Simouyé had called her house servant, Ai, to help me remove my wet garments. Ai said little, except to criticize anything done differently from the way it was done in the Teahouse of the Look-Back Tree, and this included my request to keep my clothes. They disappeared along with the servant when I wasn’t looking. I was so embarrassed, standing naked in the cool room.

Was this part of my geisha training?

I wrapped myself up in the futon and, racing into the corridor, bumped head-on into the old servant woman. Mumbling about “stinking foreigners,” she gave me a white silk robe and a cup of tea with a strange taste that burned my lips. With Ai watching me, I finished the green tea—laced with rice wine, I’m sure—then fell into a deep sleep. I awakened when I heard the sound of the scissors.

I tried to sit up, but my muscles stiffened. I cursed the gods who tied me to the floor with invisible bonds from the effects of the strong drink. I tried to move again. Nothing. My breathing became sharper when I heard voices. Girls’ voices.

They were coming back.

“She’s done us no harm, Youki-san. Why do you wish to make her lose face?”

“Is your brain as soft as duck feathers, Mariko-san?” the girl named Youki scolded. “Don’t you know what the emperor has decreed?”

Mariko answered in a timid voice, “No.”

“He has much august respect for the ways of the Westerners and he has expressed his wish our men marry white women.”

I could hear Youki rattling on about how everything was changing because of these Westerners, these speakers of English, who talked nothing but politics at geisha parties and ignored the geisha and her accomplishments. I wanted to tell her what I thought, but the effects of the rice wine made me sluggish and fuzzy-headed.

“What can we do if the emperor wishes these marriages?” Mariko asked. “We’re servants.”

“I will soon become a maiko. And if the gods smile upon your plain face, Mariko-san, someday you’ll also be a maiko.”

“I wish to be a maiko with all my heart.”

“Then why do you want this girl to get all the attention, Marikosan? What will happen to us?”

“Don’t worry, Youki-san,” Mariko assured her. “As long as men have sexual desire, there will be geisha.” Her voice was childlike yet silky, soft and smooth. I detected a longing for fulfillment in the young girl that matched my own. I squeezed my eyes shut harder, saying a prayer she would help me.

“Okâsan, mama-san, says this girl is also going to be a maiko. That means someday she’ll be a geisha,” Youki said, her words filled with ire and contempt for what she saw as a direct threat to her future.

“Are you certain this is true, Youki-san?”

“You wait and see, Mariko-san. She will capture the hearts of all the men who come to the Teahouse of the Look-Back Tree, and you and I will have nothing.”

“Nothing?” Mariko asked, her voice not believing. I began to lose hope she would help me.

“Nothing. No benefactor to give us a teahouse of our own when we’re old. We’ll be poor and worth nothing more than a sack of bones to be tossed to the dogs for their dinner. Is that what you wish, Mariko-san?”

Mariko was silent for a long moment, then she said, “The blond gaijin won’t do this to us, Youki-san. I know so in my heart.”

“I’m warning you, Mariko-san, we must rid ourselves of this girl or we’ll all pay a price to the gods who rule our fortunes.”

“No, Youki-san, I won’t let you do this terrible thing to her.”

“You can’t stop me—”

“I will stop you!”

A great rumbling followed, making my whole body shake, as if the teahouse were being torn apart by two wild animals. With great effort, I forced my eyes open.

It was true.

Two girls.

Fighting.

In spite of my drugged stupor, I could see the hazy shapes of the girls wrestling with each other, their long hair coming unbound, flowing down their backs like capes unraveling in a tempest storm. The pale yellow silk of one girl’s underrobe swirled around the pink damask kimono of the other as they pulled on the kimonos until they came undone and flew about them like the wings of birds trying to take off into flight.

Flashes of their nude skin startled me. I’d never seen girls my own age naked. My father wouldn’t allow me to attend the public baths. Bare young breasts, slim thighs, silky dark tufts of hair between their legs, they continued grappling at each other, pulling, tugging. Nothing could stop them. I suspected every inch of their beings was involved in gaining control of the other.

I flinched when I saw one of the girls grab the small scissors out of the other girl’s hand and throw them away. I tried to grab them, but the scissors slithered across the slippery floor beyond my reach. The two girls paid them no attention, pulling and grabbing at each other for what seemed like long minutes, their buttocks shaking, me watching, feeling a fluttering along my spine, as if I were awakening from a bad dream.

I’ve got to get those scissors.

My knees shook when I tried to stand up again, then buckled beneath me. My shoulders bent under the heavy weight of the liquor dominating my will, but I forced my left hand to raise slowly. Then I crawled to the spot where the scissors lay and saw my cutoff hair spread on the floor. Forget about the scissors.

I grabbed my hair. The long, blond strands slid through my fingers, but I held on to them. I heard one of the girls gasping for air when I saw her slip on the mat in her stockinged feet, knocking the breath out of her. I looked up in time to see the other girl fleeing through the paper door and sliding it shut. Then I heard the sound of feet running away.

“I have deep sorrow and must apologize for what Youki-san has done, Kathlene-san,” the girl said, breathing hard, bowing, her forehead touching the mat. She struggled to get her breath back. I know her. She was the young maid who helped me save face with Father.

“You know my name?” I asked.

“Yes.” Silence, then the girl said, “I’m called Mariko.”

“Thank you, Mariko-san.” I also bowed, though not touching my head to the mat, my gaze fixed upon the girl instead. In the dim and fluttering light I saw the red, bruising marks of the fight on her wrists and arms.

“You speak our language most precisely, Kathlene-san.”

I smiled at her compliment. It pleased me. “I studied your language at missionary school.”

The girl sighed. “I’ve often wished I were a boy so I could attend the Tokio School of English,” Mariko said with great expression. Then believing she’d said too much, she bowed her head and said in a submissive voice, “But I’m not worthy of such an honor. I’m a girl and don’t have the brain to learn about commerce and business and other things as boys do.”

“Why do you say such things about yourself?” I admonished her. “You’re as smart as any boy.”

Mariko thought for a moment, then with her eyes still lowered she said, “It’s written in Shinto belief women are impure.”

“Are you certain of that?” I asked, not wanting to offend her, but curious.

She nodded. “Buddhist teachings proclaim if a woman is dutiful enough, she can hope to be reincarnated as a man.”

“Dutiful? What does that mean?”

“I must do as my superiors have decreed.”

“And what’s that?” I asked.

“I’m born to please men, to make them feel pleasure when they mount me like a leaping white tiger,” she said without embarrassment, “to mix my honey with their milk.”

I lowered my eyes. The girl’s overt declaration about pleasing men made me uncomfortable. I didn’t know what to say, so I said, “I’m going to attend the Women’s Higher Normal School when my father comes back.”

“Please, I don’t wish to offend, Kathlene-san, but you’re pleasing your father by staying here,” Mariko offered without the least bit of sarcasm, “so are you not also pleasing men?”

I wanted to toss back a response but I was tired. Very tired. The girl’s puzzle resisted an easy answer. A more pressing question burst from my lips. “Why did you help me, Mariko-san?”

Mariko lowered her eyes, then shifted her slender body, allowing her shoulders to slump as if this was something she did at all times. “I know what it’s like to be separated from your family. It makes you different from the others.”

“Where’s your family?”

“Life in my country isn’t easy for anyone who is…dissimilar in any way,” Mariko said, not answering my question directly, which made me more curious about her. She didn’t explain what she meant, but I guessed what she was trying to tell me. Even in my small class of girls at missionary school, anyone who was different was pushed outside the accepted circle.

“I know all about your game of what you say, Mariko-san, and what you really feel.” I twisted my hair. It wasn’t all cut off, but I was still upset by what this Youki had done.

“To understand us, you must open your mind,” Mariko said, “and your heart.”

Following my instincts, I didn’t protest when Mariko bowed and motioned for me to sit down on my knees and remain there with the rustle of silk and the scent of jasmine in the air as I continued to stare at her. I wanted to learn about this strange new world of geisha and I sensed an ally in her.

I sat back on my heels, thinking. I didn’t believe anyone in the Teahouse of the Look-Back Tree but this girl wanted me to stay. Was she merely being polite to me, as was the Japanese way? I wouldn’t be surprised if later I found a knot tied in my clothes or lukewarm ashes under my bedding, common hints to urge unwanted guests to leave. But if I must be separated from my father until he came back for me, then I wanted to stay in the teahouse and become a geisha. Wanted it badly.

I wiped a hand across my face, hoping to stave off my weariness. I took a few breaths, shifting my weight, but still I suffered the inevitable onset of cramping in my legs. On the contrary, Mariko seemed relaxed and poised.

“Okâsan says Mallory-san won’t return for a long time.”

“That’s not true, Mariko-san,” I protested. “My father will come back for me. I know he will.” I clasped the small bundle of my shorn hair to my chest, my eyes filling with tears. I couldn’t help it. Let the girl think what she wanted. It wasn’t my cut-off hair that made me cry. It would grow back. It was the loss of my father that frightened me. Frightened me and made me sad.

“Okâsan says Mallory-san would never have left you in the floating world unless there was great danger.”

I squirmed. There was that word danger again. Mariko sat still, without moving, unnerving me further. I couldn’t stand it any longer. I rubbed my leg.

“Why do you call it ‘the floating world’?” I asked, hoping to take the girl’s attention away from watching me squirm in an uncomfortable position. Would I ever learn to sit as relaxed as she did?

“It’s simple, Kathlene-san. Our geisha world is like the clouds at dawn, floating between the nothingness out of which they were born and the warmth of the pending day that will disperse them.”

I didn’t understand what she was trying to tell me. My mind was dark and cloudy with worry. However curious I was about the geisha world, I couldn’t forget my father was on his way to Tokio then back to America.

“Okâsan says from this night forward we mustn’t speak of Mallory-san,” Mariko continued, then drew in her breath. Slowly.

I looked at Mariko, who was waiting for me to speak. Never speak of him again? I couldn’t. Couldn’t. Never speak of him again? I wasn’t ready to act as if my father never existed. I couldn’t dismiss the emotions pulling at my insides, so I asked her instead, “How long have you been in the Teahouse of the Look-Back Tree?”

“Since I was five years old.”

“How old are you now?”

“Fourteen.”

“Fourteen?” I said, surprised. “You look much younger.”

“Okâsan says I’m like a wildflower springing up on a dung heap.”

I shook my head. All these strange ways of speaking confused me. “What does that mean?”

“That I don’t have the face nor the figure to be part of the world of flowers and willows, but if I have endurance I will grow up to be a geisha in spite of everything in my way.”

Disbelieving, I studied her soft moon face, round cheeks and tiny pink mouth. This girl was going to be a geisha? She was so young and plain-looking. I believed geisha were mythical creatures of great beauty who started the fashion trends and were immortalized in songs. They were the center of the world of style and often called the “flower of civilization” by poets.