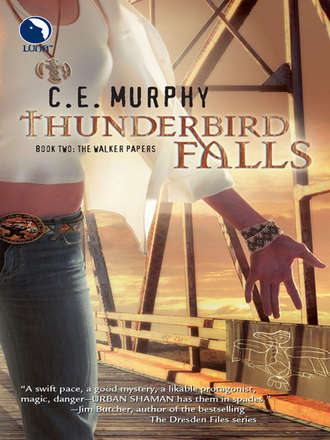

Полная версия

Thunderbird Falls

“Arright,” I muttered. “One healthy little girl for one esoteric death investigation. I guess that’s fair.” Five more minutes before calling the cops wasn’t going to make a difference to the body. “I’m here,” I said out loud, “if you want to talk.”

There was a place between life and death that spirits could linger in, a place that, with all due apology to Mr. King, I’d started calling the Dead Zone. If I could catch this young woman’s spirit there, I might just be able to learn something useful, like how she’d ended up filling a drain at the University of Washington’s gym locker rooms.

Reaching that world was easier with a drum, but somewhere in the shower room a shower leaked, a steady drip-drop of water hitting water. It was a pattern, and that was good enough. I closed my eyes. The sound amplified, deliberate poiks bouncing off the bones behind my ears. I lost count of the drops, and rose out of my body.

I slid through the ceiling, skimming through pipes and wires and insulation that felt laced with asbestos. The sky above the university was so bright it made my eyes ache, and for a few seconds I turned my attention away from the journey for the sake of the view.

The world glittered. White and blue lights zoomed along in tangled blurs, each of them a point of life. Trees glowed in the full bloom of summer and I could see the thin silver rivers of sap running through them to put out leaves that glimmered with hope and brightness. Concrete and asphalt lay like heavy thick blots of paint smeared over the brilliance, but at midmorning, with people out and doing things, those smears of paint had endless sparks of life along them, defying what seemed, at this level, to be a deliberate attempt to wipe out the natural order of the world.

Don’t get me wrong. Not only do I like my indoor plumbing and my Mustang that runs roughshod over those dark blots of freeway, but I also think that a dam built by man is just as natural as a dam built by a beaver. We’re a part of this world, and there’s nothing unnatural about how we choose to modify it. If it weren’t in our nature, we wouldn’t be doing it.

Still, looking down from the astral plane, the way we lay out streets and modify the world to suit ourselves looks pretty awkward compared to the blur of life all around it. Humans like right angles and straight lines. There weren’t many of those outside of man-made objects.

But even overlooking humanity’s additions to the lay of the land, there was something subtly wrong with the patterns of light and life. I’d noticed it months earlier—the last time I’d gone tripping into the astral plane—and it seemed worse now. There was a sick hue to the neon brilliance, like the heat had drawn color out, mixed it with a little death, and injected it back into the world without much regard to where it’d come from. It made my nerves jangle, discomfort pulling at the hairs on my arms until I felt like a porcupine, hunched up and defensive.

The longer I hung there, studying the world through second sight, the worse the colors got. Impatient scarlet bled into the silver lines of life, black tar gooing the edges of what had been pure and blue once upon a time. I had no sense of where the source of the problem was. It felt like it was all around me, and the more I concentrated on it the harder it got to breathe. I finally jerked in a deep breath, clearing a cough from my lungs, and shook off the need to figure out what was wrong. I suspected it had more to do with procrastination than anything else. I’d been warned more than once that my own perceptions could get me in trouble, in the astral plane.

It wasn’t that I was scared. Just wary. Apprehensive. Cautious. Uneasy. And that exhausted my mental thesaurus, which meant I had to stop farting around and go do what I meant to do.

Coyote had told me that traveling in the astral plane wasn’t a matter of distance, but a matter of will. It seemed like distance to me, always different, always changing. Seattle receded below me, darkening and broadening until the Pacific seaboard seemed to be just one burnt-out city, the sparks of life that colored it faded and scattered with distance. Skyscrapers that seemed to defy physics with their height leaped up around me and crumbled again, and the stars were closer.

A tunnel, blocked off by a wall of stone, appeared to my left, and I felt him waiting there. Him, it—whatever. Something was there, and it tugged at me. It laughed every time I forged past it, and every time I did I felt one more spiderweb-thin line binding me to it. The first time I traveled the astral plane I almost went to him, compelled by curiosity and a sense of malicious rightness. The second time, the stone wall was in place, my dead mother’s way of protecting me from whatever lay down that tunnel. This time I knew he was there, and it was easier to ignore him.

Someday I’m not going to be able to.

The tunnel whipped away into a wash of light, the sky bleeding gold and green around me. New skyscrapers blossomed into tall trees, filled with the light of life, but here that light was orange and red, not the blues and white I was used to. I grinned wildly and lifted my hands, encouraging the speed that the world swum around me with.

Under the gold sky, palaces built like where the Taj Mahal’s wealthy older sister grew up. A tiger paced by, sabre-toothed and feral, watching me like I might be a tasty snack. A man’s laughter broke over me, and the world spun into midnight, the sky rich and blue and star-studded. I relaxed, letting myself enjoy the changing vistas, and in the instant I did, the shifting worlds slammed to a stop.

A red man stood in front of me. Genuinely red: the color of bricks, or dark smoked salmon. His eyes were golden and his mouth was angry. “Haven’t you learned anything?”

I gaped at him, breathless. “What are you doing here?”

“You’re making enough noise to wake the dead.”

“That was kind of the idea.”

“Siobhán Walkin—”

“Don’t call me that.”

“It’s your name.”

“Don’t,” I repeated, “call me that. Not here.”

I’d become uncomfortably protective of that name: Siobhán Walkingstick. It was my birth name, the one I’d been saddled with by parents whose cultures clashed just long enough to produce me. My American father’d taken one look at Siobhán and Anglicized it to Joanne. Until I was in my twenties, no one had called me Siobhán except once, in a dream.

The last name, Walkingstick, I’d abandoned on my own when I went to college. I’d wanted to leave my Cherokee heritage behind, defining myself by my own rules. I was Joanne Walker. Siobhán Walkingstick was someone who barely existed.

But whether I liked it or not, that name belonged to the most internal, broken parts of me, and flinging it around astral planescapes made me vulnerable. I had learned to build protective shields around it, the one thing I’d managed to do to Coyote’s satisfaction over the past six months. I saw those shields as being titanium, thin and flexible and virtually unbreakable, an iridescent fortress in my mind. They were meant to protect my innermost self from the bad guys.

So I didn’t like having the two names rolled together in the best of circumstances, and I resented the shit out of having them flung around the astral plane as a form of reprimand by the very same brick-red spirit guide who’d insisted I develop the shields in the first place.

The spirit guide in question flared his nostrils, inclining his head slightly, and inside that motion, shifted. A loll-tongued, golden-eyed coyote sat in front of me, looking as disgruntled about the eyes as the man had.

“Dammit,” I said, “I hate when you do that.”

“This is not about what you hate,” the coyote said, in exactly the same tenor the man owned. His mouth didn’t move, and I was, as ever, uncertain if he was speaking out loud or in my mind. “You haven’t got the skill for this, Joanne.”

I wet my lips. “Looks to me like you’re wrong.”

“Do you really understand what you’re doing?” The coyote’s voice sharpened, making my chin lift and my shoulders go back defensively.

“I’m just trying to see if she can tell me anything about what happened, Coyote.”

“There are more mundane ways to find out. You are a policeman, are you not?”

“I’m a beat cop,” I said through my teeth. “Beat cops don’t get to investigate dead bodies in the women’s shower.”

Coyote cocked his head at me, a steady golden-eyed look that spoke volumes. Then, in case I’d missed the speaking of volumes, he said it out loud, too: “Then maybe you shouldn’t.”

Which comedian was it who said wisdom came from children, especially the mouth part of the face? I felt like he must have when he first thought it: like it would be nice to wrap duct tape around the talking part until nothing more could be said.

Coyote snapped his teeth at me, a coyote laugh. “Wouldn’t work anyway.”

“Oh, shut up.” Yet another incredibly annoying thing: he heard every thought I had, and I heard none of his. “This is supposed to be my dreamscape. Why can’t I hear your thoughts?”

He cocked his head the other way, wrinkles appearing in the brown-yellow fur of his forehead. “First,” he said, “it’s not your dreamscape. Haven’t you learned even that much? The astral plane is a lot bigger than just you or me.”

“I thought it was all basically the same,” I muttered. “How’m I supposed to know?”

“By studying,” Coyote suggested, voice dry with sarcasm. “Or is that asking too much?”

For one brief moment I wondered if it was possible that Coyote might also be my boss, Morrison.

“I’ll have to meet him someday,” Coyote said idly. I winced.

“Sure, he’ll like that a lot. Talking coyotes from the astral plane. That’ll go over well.” Morrison made Scully look like a paragon of belief. Once upon a time, our skepticism for the occult was the only thing we had in common. Then I’d done some unpleasantly weird things, like come back from the dead more or less in front of him, and now the only thing we had in common was neither of us was happy about me being a cop, though our reasons were different. “What was the second thing?” I asked, unwilling to pursue any more thoughts of Morrison.

For a moment Coyote looked blank as a happy puppy. Then he shook himself and stood up to pace, the tip of his tail twitching. “Second, you can’t hear my thoughts because I have shields, and I can hear yours because even after six months of study your shields are rudimentary and poorly crafted.”

“Thank you,” I said, “would you like me to lie down to make it easier to kick me?”

Coyote stopped turning in a circle and flashed, seamlessly, into the man-form. He had perfectly straight black hair that fell down to his hips, gleaming with blue highlights even in the star-studded blackness near the Dead Zone.

I closed up my thoughts like all the windows rolling up in a car at once, and privately admitted to myself that Coyote was a hell of a lot easier to deal with as a coyote. As a man he was almost too pretty to live, and I mostly wanted to look at him, not listen to him.

“Joanne, you took on a great power when you chose life.”

“If you say, ‘With great power comes great responsibility,’ so help me God, I’m going to kick you into last week.”

He gave me the same unblinking gaze that the coyote could. “Try it.”

A beat passed in which we neither moved nor spoke, until Coyote dropped his chin, watching me through long dark eyelashes. “You accepted this life months ago, Joanne. Why do you insist on fighting it?”

“I’m here, aren’t I?” I snapped. “Isn’t that something?”

“Something,” he agreed, but shook his head. “But not enough. Speaking with the dead is a dangerous art, and you’re not even doing that. You’re just opening yourself up and offering yourself as a conduit for anybody who has a piece to speak.”

“Yeah, so?” I admired my mature rebuttal. High school debate teams would weep to have me. “It’s all I know how to do.” Ah, a defensive attack. Good, Joanne, I said to myself, and hoped the windows of my mind were still sealed tight enough that Coyote didn’t hear me. That’ll show him you’re really the It girl. Any moment now legions of cheerleaders would leap out and rah-rah-rah their support of my rapier wit and keen discussion skills.

“That,” Coyote said with more patience and less sharpness than I deserved, “is my point. Has it occurred to you, Joanne, that I’d prefer it if you didn’t get yourself killed out here?”

I blinked, and swallowed.

“Why are you so afraid?” he asked, much more softly.

There are questions a girl doesn’t want to answer, and then there are the ones she doesn’t even want to think about. I reached out, around Coyote and beyond him, for the Dead Zone.

The stars shut down and the world went blank.

CHAPTER THREE

In time, stars began winking in and out again, solitary dots of light that made me feel like a single extremely small point on an endless curve of blackness. I was cold beneath my skin, but when I touched my arm, my body temperature seemed normal. I didn’t remember the chill in the Dead Zone before. It was as if it was tainted, too, with the same subtle wrongness that had marred Seattle.

I held my breath and turned, one slow circle, reaching out with my hands and my mind alike. The former felt nothing.

The latter encountered pain.

It rolled through me, a bone-cold ache that settled in my spine at the base of my neck, creating a headache. Ice throbbed into my veins with every heartbeat. My skin was flayed from my flesh and my flesh from my bones, knives thrusting into my kidneys and cutting out my heart. My bones broke, crushed by a weight of regret that lay heavier than the sea. It dragged me down to my knees, too weak from a hundred billion lifetimes of mistakes to bear up any longer.

And rapture shattered through me, turning the ice in my blood to golden heat. I staggered to my feet again, fire in my lungs so pure it seemed I could breathe it. Burning tears scalded my face, tracks following a thin scar to the corner of my mouth. I swallowed them down, not caring that they seared my throat.

Disbelief caught me in the belly, a bowel-twisting moment of realization that culminated in the words, “Oh, shit,” when I knew I couldn’t stop the carcrash-bombexplosionrunawayhorsetrainwreckshipsinking followed by relief and dismay, to put down the burden of a body after secondsminuteshoursdaysyearsdecades-centurieseons of life.

Dimly, I was aware that I was connected, hideously and intimately, to everything that had ever died.

More immediately, I understood that now I was going to die. Again. For good.

Then somebody hit me in the face. New, fresh pain blossomed, shattering all the old. I clapped both hands to my nose, doubling over and shrieking.

Note to self: grabbing a broken nose does not, in any fashion, help. Lightning shot through my head in blinding stabs of agony. I made a retching noise and fell to the ground, knocking my forehead against the featureless planescape. Brightness flashed in my eyes. I closed them, grateful for the ache in my skull that took a little away from the shards of pain in my nose. “Mother of Christ.”

I rolled onto my side, panting, and gingerly put my hand over my nose, envisioning a Mustang with a dented hood as I did so. Undenting it was easy: stick a suction cup over it and ratchet up the pressure until it popped back into place. In my mind’s eye, the dent banged into shape. I opened my eyes, relieved.

Pain slammed through my nose and stabbed me in the pupils. I shot to my feet, clutching my nose more cautiously, and stared accusingly at Coyote.

“This is the realm of the dead, Joanne,” he said with a shrug. He was back in coyote form, his narrow shoulders twitching lankily. “It’s not a place for healing.”

None of the things that came to mind were very ladylike. I managed to hold my tongue, but Coyote tilted his head at me and gave a very human snort of derision. “Nice girls don’t think things like that.”

“Thank you for getting me out of that,” I said without the slightest degree of genuine gratitude. I hadn’t felt even a hint of the healing power that normally boiled behind my breastbone when I envisioned fixing my nose. I should’ve known it hadn’t worked.

“You’re welcome,” Coyote said, not meaning it any more than I had. “Can we go now?”

“No, we’re here. I might as well see if I can find her.”

Coyote sighed, a tremendous puff of air. “All right. What’s her name?”

“I don’t know.”

I didn’t know dogs could look scathing. I thought they were supposed to be all about supportive looks and hopeful puppy eyes. Coyote turned a scathing look on me anyway.

“I’m not,” he said through his teeth, which seemed larger and whiter and much pointier suddenly, “a dog. How do you expect to find someone in the realms of the dead if you don’t even have a name to start with?”

“The others just met me here,” I said uncomfortably. Coyote said something in an Indian language I didn’t know, but I didn’t really need a translation. The tone was enough.

“When you get out of here,” he went on, “if you don’t find a teacher I’m going to…” He snapped his teeth.

“Bite me?” I supplied, as helpfully as I could. He snapped his teeth again.

“The others met you here,” he said, instead of completing the threat, “because you invited them to contact you. They drew you here through their skill. This time you’re on your own.”

“Am not. I have you.”

This time he said, “Ministers and angels of grace defend us,” in English, and shifted back into his human form, stepping forward to put his hands on my shoulders. I blinked. Aside from hitting me in the face a few minutes ago, I couldn’t remember him having touched me before. “Have you no sense of self-preservation at all, Joanne? Are you—” Sudden clarity lit his gold eyes to amber, and his chin came up with evident surprise. “Ah,” he said more quietly, and let me go.

“What? What? Am I what?”

“I think we’d better try to do what you came to do, and get out of here.” He stepped away from me. A strangled sound of frustration erupted from my throat. “This is a dangerous place for you, in more ways than one. Tell me what you know about this girl, and we’ll see if we can find her.”

I told him what I knew: young, black, dead in the shower of the women’s locker room. It was pathetically little, and I began to feel embarrassed. “Focus on her,” Coyote said. “Focus on what she looked like. If we’re lucky she won’t have lost her body sense yet, and we’ll be able to find her that way.”

“And if we’re not?”

“Then we’re going home and you’re going to have to do your research the old-fashioned way. I don’t want you to be here.”

I muttered under my breath as I closed my eyes, constructing an image of the dead girl behind my eyelids. She’d been pretty, with round cheekbones and a pointed chin. Her hair was short with kinky curls, a few of them bleached and dyed fire engine-red. She was dark-skinned, even in death, and I tried to imagine away the ashy blue that had tinged full lips and discolored her fingernails.

A chill slid down my back, slow and thick, like cold blood wending its way around my spine. Fine hairs stood up all over me, sweeping in waves until I shivered and shook my hands. “I’m sorry,” I said, eyes still closed. “I can’t do any better.”

Coyote’s voice came from a long way away, echoing as if through a cavernous chamber. “I think you’ve done more than well enough.”

I opened my eyes.

Snakes.

Snakes were everywhere, winding through the empty blackness of the floor like sanguine rivers, curdling in spots and making pools of heart’s-blood red. They wrapped around my ankles and crawled up my thighs, invasive and intimate. One twisted itself around my waist and ribs and lifted its face to mine, a hissing, flickering tongue tasting my breath. Smelling me and seeing me. Fangs curved dangerously past its wide-open lower jaw, drops of venom forming and splashing away. It didn’t blink; I couldn’t. “Coyote?” I could barely hear myself.

“I can’t help you.” He sounded even farther away. I dared to turn my head, the smallest motion I could manage, very aware that doing so exposed my jugular to the snake. It hissed softly, dropping its jaw wider.

Coyote was no longer off to my right. No, he was, just at an impossible distance, a speck of man-shape among the sea of snakes. They roiled and bubbled over one another, making the floor a living thing, and as I watched they began to drip from the emptiness above me.

I was caught in a Salvador Dali painting gone horribly wrong.

I laughed. It reverberated, short and broken, off the nonexistent walls of the Dead Zone. The snake around my middle tightened and hissed, bringing its head closer to my throat. My laughter cut off with a shudder.

Garter snakes, crimson and russet, crept up my body, tangling around my fingers and extending like writhing talons. They nestled through my hair until I could see them wriggling in my line of vision, making me a modern-day Gorgon. “Coyote, what’s happening?” My voice was scared and thin, just the way I hadn’t liked hearing Phoebe sound.

There was no answer from the trickster.

The snake at my waist still watched me. I felt my pulse jumping in my throat like a frightened mouse and ducked my head, trying to hide it from the snake. “What do you want?”

It drew its head back, flaring a hood, and hissed at me. My knees locked up, keeping me from bolting, but I didn’t know if that was good or bad. “What do you want?” I managed a second time. The snake spat, venom flying past my face so close I thought I could feel it burn. Then it twisted its head away from me without releasing its grip around my middle, focused on something I couldn’t see.

The Dead Zone heaved with a bloody mass of bodies, seething and knotted reptiles washing around one another in sea-sickening motion. A wave broke through them, like a submarine cruising just beneath the surface, displacing water without being visible. Then the surface ruptured, spraying frightened, twisting snakes through the air. They wriggled frantically, clutching at unsupportive sky, and collapsed soundlessly back down into the melting mess of serpents.

The thing that looked down at me was not at all like a submarine. Monster leaped to mind, and then a narrower classification: sea serpent. Why I was worried about the very specific kind of monster I was facing was beyond me, but the label hung in my thoughts as the thing reared up above me.

It was massive. It had a weight to it unlike anything I’d seen in the Dead Zone, a heaviness that seemed to bear down like the guilt and pain I’d experienced moments ago. There was no sense of being dead about the serpent. I wasn’t sure I’d ever seen anything so alive or so filled with purpose. It lived, and it lived to kill.

Its scales were black, fastened together like intricate armor, and gleamed so hard against the darkness of the Dead Zone they hurt to look at. It flared out a ruff, exposing gills that glittered and sparkled with hard edges. Tentacles, like Medusa gone mad, waved around its head. It had no legs, but the word snake fell pitifully short. Ridges crested its back, sharp and deadly. Even in the half-light, it looked as if the spires glistened with poison. It coiled higher, enough strength visible in its body to crush a ship. If this was the kind of thing that had inspired ancient mariners to their warnings of Here Be Dragons, I couldn’t blame them for wanting to avoid the unknown areas of the sea. It opened its mouth to hiss at me.

Its fangs were nearly as long as I was.

I wondered if I would stop feeling right away, or if I’d be alive a while inside the serpent’s maw, feeling the muscle of its throat crush me as it swallowed me down.

The smaller snakes began to drop off me, slithering down my arms and legs again and falling to the floor. I couldn’t blame them: I didn’t want to be facing their lord and master, either. One wriggled under my shirt and down my spine, then panicked, thrashing around, when it met the taut muscle of the snake around my ribs, blocking its passage. The snake around my ribs whipped its head around, pinning my arm against my body as it sank its teeth into the littler one under my shirt. The smaller reptile spasmed, flailing under my shirt in its death throes. Its cold terror seeped in through my skin, leaving me in an icy sweat. I stared up at the monster, feeling the snake die, little and boneless against the small of my back.