Полная версия

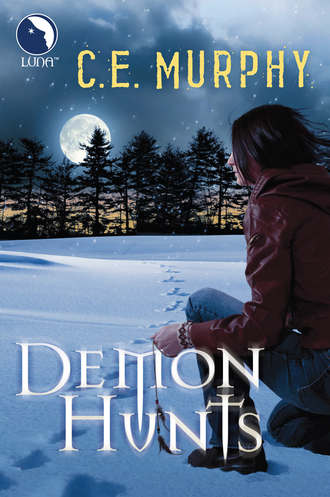

Demon Hunts

“December twentieth, why?”

I’d known that. I’d known it very clearly, because tomorrow was the first anniversary of my mother’s death. I’d only asked in order to buy time. Sadly, the second and a half it took Billy to answer wasn’t nearly as much as I’d hoped to buy, and it didn’t give me any way out of proposing a supernatural hypothesis. “Tomorrow’s the solstice. These things tend to get stronger around the pagan high holy days.”

Pagan high holy days. Like half of them—more than half—weren’t marked in some way by the modern world and practitioners of most modern religions. Easter fell suspiciously close to the spring fertility festival of Beltane, midsummer meant a weekend of partying while the sun didn’t go down, and I didn’t think there was much of anybody fooling themselves about Christmas lying cheek-by-jowl with the midwinter solstice. Mardi Gras, Halloween—they were all tied in with ancient holy days, even if we didn’t always consciously draw the lines between them. I snorted at myself and shook it off; it didn’t really matter who celebrated them or what they were called. The point was, certain times of the year had natural mystic punch, and we were on the edge of one of those days today. That didn’t exactly comfort me.

Neither did the fact that banshees seemed inclined to swarm during the holy days. Twice this year I’d faced them, and I was in no particular hurry to go up against one again. They worked for a much bigger bad, a thing they called the Master. I only knew a handful of things about him, but none of them was good.

No, that wasn’t true. One of them was good: as far as I could tell, he wasn’t corporeal. No killer demon walking the earth. That was a win, and I’d learned to be grateful for small favors.

Everything else about him, though, scared the crap out of me. I knew he found me amusing, and it was my general opinion that being found amusing by alarmingly powerful entities was not something to be sought. I also knew that ritual murders, carried out by his banshee minions, fed him enough strength to keep an eye on the world. I knew he could come a hair’s breadth from killing a god, and I knew the only reason I wasn’t already dead was my mother had sacrificed herself to keep me alive.

I very much didn’t want Charlie Groleski’s and Karin Newcomb’s shriveling forms to be the work of banshees, because that meant the Master was stirring, and I’d already pissed him off twice this year. Unfortunately for me, that’s what experience suggested we were looking at.

“Joanne?” Billy put his hand on my shoulder, startling me out of my grim examination of the bodies. “You okay, Walker?”

“Are the bodies exsanguinated?”

My partner gave me a look usually reserved for his kids mouthing off. “You know they aren’t. You just wanted an excuse to use ‘exsanguinate’ in conversation.”

I flashed him a guilty little smile that turned back into a frown. “Yeah, but maybe it’s good that they’re not, since the winter moon murders were all pretty much drained of blood. Even if it’s banshees again, this is different.”

“If it’s banshees again I’d rather it was the same, so we’d have a pattern to follow. Holy shit!” Billy levitated about four feet back, with me right beside him, as Groleski’s body fwoomped into a much smaller mass. Dust rose up, lingering in the air, and Billy all but vaulted another slab to snatch up medical masks. He tossed one to me and put one on, eyes bugged above its white line. “What the hell was that? Where’s the doctor?”

“Here, Detective.” A red-haired woman wearing medical glasses over her own mask swept in, hurrying but not alarmed. “You did ask me to step outside.”

We had, because although Sandra Reynolds had been the coroner on this case for the past six weeks, neither Billy nor I had wanted to stand around discussing things like banshees in front of her. She’d been watching through the window of the observer’s room, the place where families were most often taken to identify the bodies of their loved ones. It wasn’t soundproofed, but with the door closed it was unlikely she’d have overheard us running through mystical answers to our murders. Magic didn’t seem like her thing. She picked up a slim metal rod and bent over Groleski’s deflating body, dust poofing up to mar her safety glasses. I felt a shock of relief she was wearing them. I had no reason to think the particles were dangerous, but then, I didn’t have a reason not to think so, either.

Groleski flattened a little more as she edged the rod through his remains. I was glad I hadn’t poked him after all. The guilt of making him collapse like that would’ve kept me awake for days. Reynolds muttered, “This is fascinating,” in a tone that suggested that it was genuinely fascinating, and also a pain in the ass. “None of the other bodies have shown this kind of exsanguination.”

I shot a triumphant look at Billy, who rolled his eyes as the doctor continued, “It’s not just blood loss. A thawing body should be—” she glanced at us and clearly decided to go for a non-technical term “—squishy. I have no explanation for the rapid decay into dust.” Apparently quite happy, she scraped a pile of Charlie’s remains into a test tube and stoppered it. “I’m going to have to take a look at this.”

“So,” I said much more quietly, “am I.”

I hadn’t been using the Sight, mostly because it’d shown me nothing useful when we’d come across the bodies in the first place. I let it slip over my vision now, and watched a trail of red and yellow sparks follow Dr. Reynolds out of the morgue. I’d heard guys on the force call her a spitfire, and thought her aura colors reinforced that.

To my dismay, hers was the only aura I got a read on. There were no hints of dark magic clinging to the disintegrating bodies. They just looked dead. I glanced at Billy just to make sure my mojo was working, and got a reassuring flare of his orange and fuchsia colors. Well, reassuring in that I wasn’t defective. Less reassuring in that I was still batting zero in the paranormal detecting ballpark. “Morrison’s not going to like this.”

Worry sharpened Billy’s voice: “Not going to like what? What do you see?”

“Nothing.” I leaned against the nearest non-body-carrying slab and pulled my mask down. “You don’t need that thing. There’s nothing more dangerous there than any long-dead body might be carrying.”

Billy tugged his own mask down. “Like bubonic plague, you mean?”

I snorted, waving him off. “They’re not that long dead. And besides, aren’t most of the annual cases of plague in this country in, like, Arizona? No, what Morrison’s not going to like is I’m still not getting anything. If they weren’t falling apart like rotting…” I couldn’t think of anything that fell apart like they were doing, and finished, “…corpses,” lamely. “Anyway, I’d just think it was natural if it wasn’t happening so fast. I don’t like to go back to the captain with nothing.”

“None of us do.”

“Yeah, but…” There was nothing to say after that, because the sentence would end “but you don’t have a crush on him,” if I was being flippant, and with the same sentiment expressed in weightier terms if I was being brave. I wasn’t brave. Or flippant, for that matter, because even though it was an embarrassingly open secret, I wasn’t actually in the habit of going around admitting I’d sort of fallen for my captain. I didn’t even like admitting it to myself.

Billy, who was a better man than I, said, “So how do we find something to go to him with?” instead of taking the opportunity to razz me.

“I have two ideas. Do you want to hear the one you’ll be okay with or the one you’ll hate first?”

He stared at me. “If I say the one I’m okay with, is there any chance I won’t have to hear the one I’ll hate?”

I held my fingers an inch apart. “A little one.”

“Let’s go with that, then.” He folded his arms across his chest and glowered at me, which would have been thoroughly intimidating if I was one of his children.

“Okay. We go talk to your friend Sonata and see if she’s in tune enough with the dead to get a rise out of any of our murder victims. We also find out if she knows anybody who can diagnose a decomposition like this one, because it’s obviously not natural. Then we go to Morrison with whatever we’ve learned.”

“This is the better idea? Share case details with someone outside the force? How much will I not like the other one?”

“A lot.” I tilted my head toward the door. “So shall we go talk to Sonny?”

Sonata Smith outclassed Billy by a mile in the rank of speaks-with-the-dead. She was in her sixties and lived in a gorgeous old Victorian up on Capitol Hill, exactly the kind of house I’d imagine a medium lived in. That, though, was the end of where she conceded to meet my expectations. Her séance partner was a surfer-boy-looking former theology student in his early thirties, and she liked wearing violent comic book T-shirts, neither of which seemed very peaceable and medium-like to me. On the other hand, Billy was a six-foot-two police detective with a fondness for yellow sundresses, so I should’ve known better than to try to lay expectations on what constituted typical behavior for a medium. Or anybody else, probably.

Either way, Sonny was one of the relatively few Magic Seattle people I knew, and pretty much the only one I trusted besides Billy and Melinda. Left to my own devices, I’d managed to meet up with entirely the wrong crowd, so I was happy to lean on Billy’s expertise instead of my own shaky judgment.

We’d called ahead, but Sonny still pursed her lips as if we were unexpected when she answered the door. After a moment she rearranged the expression into a smile and said, “William, Joanne, come in,” and stepped aside. We got about two steps past the threshold before she said, “I take it this is about the murders. Can I get you some tea?”

Billy and I exchanged looks, and I put on a patently fakey smile. “At least Morrison can’t be pissed if everybody’s already talking about them, right?”

“Not everyone,” Sonata said. “Just that awful woman on Channel Two. She broke the story this morning. The Seattle Slaughterer, they’re calling him.”

I winced from the bottom of my soul all the way out. Billy groaned. “Tea would be great, Sonny. Green tea is supposed to be good for you, right? Would enough of it make somebody invulnerable? Because Joanie’s going to need it.” He followed Sonata into the kitchen, and I trailed along behind, wondering how many different ways Morrison was going to kill me. I’d gotten up to four highly creative ways to die before Sonata got us seated at the table and put a kettle on to boil.

“I’m afraid not,” she said. “I don’t know of anything that’s that good for you.”

Billy, more cheerfully than I thought was appropriate, said, “You’re dead,” to me.

I dropped my forehead to the table and said, “Maybe not,” words muffled by the shining wood. It smelled faintly of lemon Pledge, old and familiar. “Neither of us can pick up anything at all from the bodies we’re finding, Sonny. Even the one this morning didn’t have a ghost lingering, and she was freshly dead. I was thinking maybe if you gave it a shot, or if you knew somebody who could…” I peeked up, trying for convincing puppy-dog eyes.

Sonata looked unmoved, not even blinking when the kettle suddenly whistled. She let it go on, piercing the air, and finally shook her head. “I know who should be able to help.”

I sat up, hope surging in my chest as Sonata went to take the kettle off. “Who?”

She turned her profile to me, concern thinning her lips. “Joanne, it should be you.”

CHAPTER SIX

The kettle’s whistle faded into a rush of staticky background noise that lingered underneath, then swallowed, Sonata’s words. I was vaguely aware of Billy’s grimace, but mostly I was paying attention to the hiss between my ears and the abiding feeling that I should have expected Sonata to say something like that.

Three or four thousand self-directed recriminations lined up to pile themselves on me. If I hadn’t done this, if I’d only done that—I had a list of mistakes longer than my arm. It was all too easy to believe that by foundering around as I’d done the past year, I’d missed the mark on where I was supposed to be standing. Back in January, when everything had started and I’d been burning with power released after years of imprisonment, there’d been one brief and kind of glorious moment when I’d believed I could save, or heal or protect the whole city of Seattle. I’d lost most of that confidence while struggling to learn about my talents, but apparently I hadn’t lost the sensation that I should be able to do something like that. That I should, in essence, be so much better than I was.

Memory caught me in the gut, a visceral recollection of an alternate timeline I’d briefly been given viewing access to. There’d been a woman a lot like me in that other world, only she had her shit together. She had a life, a family, friends and she would have known how to hunt down whoever was killing and snacking on Seattleites. For a moment I ached with the regret of not being her.

But—and this was the crux, and always would be—she had never chosen to come live in Seattle. Whatever battles she had to fight, they were somewhere else, with someone else. This was the path I was on, and if I’d screwed up, well, that was life. I was finally starting to wrap my mind around the idea of making things better in the future instead of beating myself up for things that had gone wrong in the past. Maybe it wasn’t much, but it had to be enough.

I spread my fingers wide on the shining kitchen table, and made my voice louder than the blood rushing in my ears. The moment of believing I could protect Seattle came back to me, but like through a fun-house mirror: it was a little too far away, a little too distant to feel real. “You’re probably right. It probably should be me. Here’s the thing, though, Sonny. I hardly even know what that means. Can you…” I got up, suddenly unable to hold still, and stalked across the kitchen, trying not to look at either Billy or Sonata.

“Can you tell me what’s missing? What…what I should be? God, what a stupid question. It’s just that I’m so far behind the curve I can’t even see it. I don’t know what’s wrong, much less how to fix it. If I can understand…” I spread my hands again, this time against the air, and made myself meet the others’ eyes. “Some hero I am, but right now I don’t have any idea where to start.”

Tension turned to uncomfortable sympathy in Sonata’s gaze. “For what it’s worth, Joanne, it wasn’t until I met you that I began to understand, myself. William…?”

Billy shook his head. “I’m not part of the scene like you are, Sonny, you know that. For me it’s mostly what I can do through the job. You’re my one real contact with the world.”

“Why is that?” I interrupted, genuinely surprised. “You’re like a true believer, Billy. Why aren’t you neck-deep in it?”

“Mostly because of Brad.”

“Oh.” I wished I hadn’t asked. Doctor Bradley Holliday was Billy’s older brother. They’d had a sister, too, Caroline, who’d been between them in age, but she’d drowned in an accident when she was eleven. Her bond with Billy had kept her ghost at his side for thirty years, and that had driven a wedge between the brothers. I wasn’t certain whether it was envy or anger or some combination thereof, but Brad had never taken to the paranormal the way Billy had. It’d never occurred to me that maybe Billy hadn’t embraced it as much as he’d have liked, in order to keep a degree of peace in the family.

Or maybe he’d embraced it just as much as he needed to. I knew he and Melinda had met at a conference about the paranormal. Fifteen years and five kids later it didn’t look, from the outside, like he was missing too much.

“We had a disaster last year,” Sonata said quietly. “Within the community, at least, it was a disaster. This city had a number of genuinely powerful protectors, Joanne. Shamans, mostly. People who mitigated the world’s effects, both meteorological and anthropological.” A brief sad smile turned one corner of her mouth. “They were one of the reasons Seattle had a reputation as a good place to live.”

A space in my belly turned hollow and worried. “They all died, right? Hester and Jackson and…”

Pure surprise wiped Sonata’s sorrow away. “That’s right. You knew them? Roger and Adina and Sam?”

I sat again, suddenly weary. “I met them. I met them after they died.” They, as much as Coyote, had set me on a shaman’s path.

Sonata, who communed with the dead, didn’t even blink at that confession. Instead she said, “A few others left, after the murders. They were afraid, and that fear poisoned their ability to help the city, so maybe it was the right choice. But it left Seattle vulnerable. I thought we would have to simply work it out, that we’d eventually draw new talent back to us. But then I met you.”

“And you realized the new talent was here in a shiny incompetent package.”

Sonata pursed her lips. “I wouldn’t have put it that way. You’re not incompetent, merely…”

“Uneducated.” Really, not even I thought I was genuinely incompetent, not anymore. When push came to shove I had so far managed to get the job done, so I probably wasn’t actually incompetent. Inept, inexperienced, ill-equipped, yes, but those all had a little less sting than incompetency. “How can you tell I’m supposed to be the one who steps up? How can you tell I’m worth half a dozen other shamans?”

“You single-handedly destroyed the black cauldron.”

I wet my lips and caught Billy’s gaze. “That wasn’t technically me.”

To my surprise, he shook his head. “Sonata’s right, Joanie. That was pretty close to impossible. The cauldron was hundreds, maybe thousands, of years old, and imbued with enough magic that it essentially had a life of its own. You know what getting near it felt like.”

I did. It was seductive, calling me home to a promise of rest and peace. Not even gods were immune to its song. But I clung to a stubborn thread of denial. “Billy, I didn’t destroy it. You know that.”

“I know that over the cauldron’s whole history there are stories of people trying to break it. In all that time, you were the only one who pulled all the right elements to her so that it could be shattered. It wasn’t your sacrifice, but I think it was your presence as a nexus that made it possible.”

I wailed, “But what if I’d moved to Chattanooga?” and they both looked at me before Sonata laughed.

“Then perhaps the cauldron would have gone to Chattanooga. You’ll drive yourself crazy if you start wondering down those lines, Joanne. We can’t know what might have been.”

I thought of the alternate self whose life I’d seen glimpses of, and clamped my mouth shut on an I can. It hadn’t, after all, been my talent that let me see a dozen different timelines. “Okay. One more stupid question, and then I promise to go…” Save the world seemed a little melodramatic, so I went with “stop the killer,” and added, “somehow,” under my breath.

Out loud, I said, “Does every city have a group of shamans like Seattle did? People who try to protect the place?”

“Many do. There are…” Sonata sighed and went back to the counter, brewing the tea that had been abandoned. “There are both more and fewer shamans, or adepts of any kind, than there have ever been, Joanne. More, because there are more people than ever before. Fewer, because…”

“Because there are more people than ever before.” I mooshed a hand over my face. “Five hundred years ago there’d have been a shaman in every tribe, maybe. One person for a few hundred, maybe a few thousand, individuals. Now there’re billions of people, and any given shaman has tens of thousands to tend to. Right?”

“In essence.”

I blew a raspberry. “Why aren’t there more…adepts?” I liked that word better than “magic users”, probably because people could be adept at lots of things and I could at least pretend I wasn’t talking about the impossible as if it were ordinary. The whole train of thought led me to snort at my own question before anyone had time to answer. “Like Joanne the Unbeliever has to ask.”

“It’s partly an artifact of the era,” Sonata agreed, then glanced at Billy, who looked uncomfortable. I sat up straighter, ping-ponging my gaze between them, and Sonata sighed again. “The last twelve months have been hard on the magic world, Joanne. More of us have died than usual. It’s like a catalyst was set.”

Oh, God. I said, “Was that catalyst me?” in a small voice, and to my undying relief, Sonata’s frown turned into a quick shake of her head.

“I don’t think so. I could be wrong,” she amended hastily, “but you strike me as the response, Joanne. When I look at you I see the answer to, not the start of, the troubles.”

The hollow place in my belly came back. My brain disengaged from my mouth and went distant, surprised to hear the question I voiced: “Do you know an Irish woman called Sheila MacNamarra?”

Sonata’s eyebrows went up. “Should I?”

“I don’t know. She was an…adept. As far as I can tell, she spent her whole life fighting—” I broke off, looking for a less dramatic phrase than what leaped to mind, then shrugged and used it anyway. “Fighting the forces of darkness. She went up against the Master, the one who created the cauldron. More than once, even. I think that was sort of what she…did.”

Recognition woke in Sonata’s eyes. “The Irish mage. I know of her. I didn’t know her name.”

My heart leaped and a fist closed around it all at once, sending a painful jolt through my chest. “You’ve heard of her? What do you know about her?”

Because what I knew about Sheila MacNamarra was embarrassingly limited. She liked Altoids; that was almost the sum total of what I’d learned about her in four months of traveling at her side. It was only after she died that I discovered she was an adept of no small talent, and that she’d spent her life fighting against—to put it extravagantly but accurately—the forces of darkness.

It was only after she died that I learned how far she’d gone to protect me.

Sonata was nodding. “I know of her as a power, yes. We don’t use names often, Joanne. You should know that by now. And mages are by their nature reclusive. As far as I know, no one’s seen the Irish mage outside of her homeland in decades. I’ve never even heard of anyone going to study with her, which is a little unusual. I don’t know if she has any protégés.”

“One,” I said. “In a manner of speaking.”

It would have taken a dolt to miss the implications, and while Sonata was a bit of a long-haired hippy freak, she was by no means stupid. She sharpened her gaze on me, eyebrows shooting up again, this time making a question all of their own.

“She was my mother,” I said tiredly, “and she died a year ago tomorrow.”

I didn’t typically think of myself as an emotional lightweight. I didn’t tear up at Hallmark commercials, although extreme vehicle makeover shows could get me. I had a secret stash of romance novels that didn’t fit my girl-mechanic image, but even when they got angsty I didn’t sniffle over them. I had not, in fact, cried when my mother died. I’d barely known her, and I hadn’t liked her very much. But for some reason my throat got painfully tight and my nose stuffed up as I made my announcement.

Billy and Sonata were conspicuously silent, for which I was grateful. After a couple deep breaths I regained enough equilibrium to say, “She gave me to my dad when I was just a baby, because she had to keep fighting the Master.” That was so inaccurate as to be an outright lie, but I didn’t feel like getting into the complex time-slip that had happened both nine months and almost thirty years ago in my personal timeline. “Would her death be enough to start messing up the balance? Was she that big a gun?”

Sonata’s eyes were dark. “What’s your calling, Joanne? What are you, in adept terms? What are we?”

“Me? I’m a shaman. You two are mediums. Melinda’s, I don’t know, a witch or something. Why?”

“And what do you suppose a mage is?”

“I don’t know. It’s a wizard. A sorc…” Except sorcerer, in my experience, connotated bad guy, and I was pretty damned sure Sheila MacNamarra hadn’t been a bad guy. I fell silent, staring at Sonata and working through the rankings I was aware of.