Полная версия

Hidden Warrior

HIDDEN WARRIOR

Book Two of the Tamír Triad

Lynn Flewelling

Copyright

Voyager An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpervoyagerbooks.co.uk

This edition published in 2003

Copyright © Lynn Flewelling 2003

The Author asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Source ISBN: 9780007113101

Ebook Edition © MARCH 2016 ISBN: 9780007401604

Version: 2016-03-14

Dedication

For my father

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

The Skalan Year

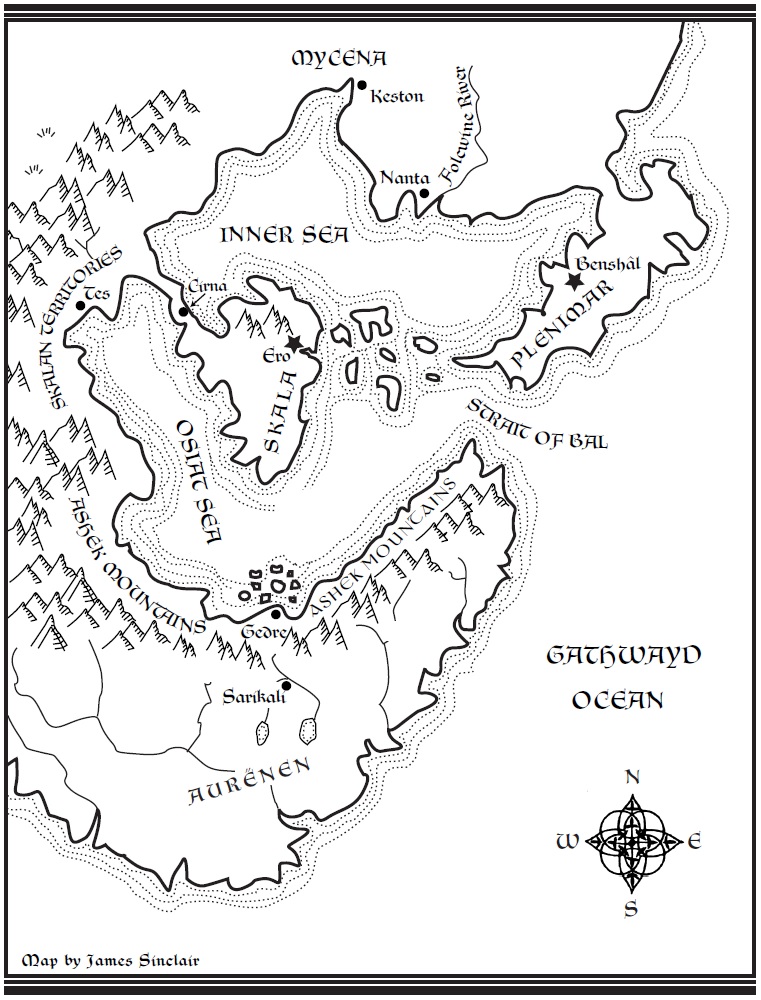

Maps

PART I

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

PART II

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

PART III

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

PART IV

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Chapter 55

Chapter 56

Chapter 57

Chapter 58

Chapter 59

Chapter 60

Keep Reading

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Also by the Author

Praise for the BONE DOLL’S TWIN

About the Publisher

The Skalan Year

I. WINTER SOLSTICE—Mourning Night and Festival of Sakor; observance of the longest night and celebration of the lengthening of days to come.

1. Sarisin: Calving

2. Dostin: Hedges and ditches seen to. Peas and beans sown for cattle food.

3. Klesin: Sowing of oats, wheat, barley (for malting), rye. Beginning of fishing season. Open water sailing resumes.

II. VERNAL EQUINOX—Festival of the Flowers in Mycena. Preparation for planting, celebration of fertility.

4. Lithion: Butter and cheese making (sheep’s milk pref.) Hemp and flax sown.

5. Nythin: Fallow ground ploughed.

6. Gorathin: Corn weeded. Sheep washed and sheared.

III. SUMMER SOLSTICE

7. Shemin: Beginning of the month—hay mowing. End and into Lenthin—grain harvest in full swing.

8. Lenthin: Grain harvest.

9. Rhythin: Harvest brought in. Fields plowed and planted with winter wheat or rye.

IV. HARVEST HOME—finish of harvest, time of thankfulness.

10. Erasin: Pigs turned out into the woods to forage for acorns and beechnuts.

11. Kemmin: More plowing for spring. Oxen and other meat animals slaughtered and cured. End of the fishing season. Storms make open water sailing dangerous.

12. Cinrin: Indoor work, including threshing.

Maps

PART I

I ran away from Ero a frightened boy and returned knowing that I was a girl in a borrowed skin.

Brother’s skin.

After Lhel showed me the bits of bone inside my mother’s old cloth doll, and a glimpse of my true face, I wore my body like a mask. My true form stayed hidden beneath a thin veil of flesh.

What happened after that has never been clear in my mind. I remember reaching Lhel’s camp. I remember looking into her spring with Arkoniel and seeing that frightened girl looking back at us.

When I woke, feverish and aching, in my own room at the keep, I remembered only the tug of her silver needle in my skin and a few scattered fragments of a dream.

But I was glad still to have a boy’s shape. For a long time after I was grateful. Yet even then, when I was so young and unwilling to grasp the truth, I saw Brother’s face looking back at me from my mirror. Only my eyes were my own—and the wine-colored birthmark on my arm. By those I held the memory of the true face Lhel had shown me, reflected in the gently roiling surface of the spring—the face that I could not yet accept or reveal.

It was with this borrowed face that I would first greet the man who’d unwittingly determined my fate and Brother’s, Ki’s, even Arkoniel’s, long before any of us were born.

Chapter 1

Still caught at the edge of dark dreams, Tobin slowly became aware of the smell of beef broth and a soft, indistinct flow of voices nearby. They cut through the darkness like a beacon, drawing him awake. That was Nari’s voice. What was his nurse doing in Ero?

Tobin opened his eyes and saw with a mix of relief and confusion that he was in his old room at the keep. A brazier stood near the open window, casting a pattern of red light through its pierced brass lid. The little night lamp cast a brighter glow, making shadows dance around the rafters. The bed linens and his nightshirt smelled of lavender and fresh air. The door was closed, but he could still hear Nari talking quietly to someone outside.

Sleep-fuddled, he let his gaze wander around the room, content for the moment just to be home. A few of his wax sculptures stood on the windowsill, and the wooden practice swords leaned in the corner by the door. The spiders had been busy among the ceiling beams; cobwebs large and fine as a lady’s veil stirred gently in a current of air.

A bowl was on the table beside his bed, with a horn spoon laid out ready beside it. It was the spoon Nari had always fed him with when he was sick.

Am I sick?

Had Ero been nothing but a fever dream? he wondered drowsily. And his father’s death, and his mother’s, too? He ached a little, and the middle of his chest hurt, but he felt more hungry than ill. As he reached for the bowl, he caught sight of something that shattered his sleepy fantasies.

The ugly old rag doll lay in plain view on the clothes chest across the room. Even from here, he could make out the fresh white thread stitching up the doll’s dingy side.

Tobin clutched at the comforter as fragments of images flooded back. The last thing he remembered clearly was lying in Lhel’s oak tree house in the woods above the keep. The witch had cut the doll open and shown him bits of infant bones—Brother’s bones—hidden in the stuffing. Hidden by his mother when she’d made the thing. Using a fragment of bone instead of skin, Lhel had bound Brother’s soul to Tobin’s again.

Tobin reached into the neck of his nightshirt with trembling fingers and felt gingerly at the sore place on his chest. Yes, there it was; a narrow ridge of raised skin running down the center of his breastbone where Lhel had sewn him up like a torn shirt. He could feel the tiny ridges of the stitches, but no blood. The wound was nearly healed already, not raw like the one on Brother’s chest. Tobin prodded at it, finding the hard little lump the piece of bone made under his skin. He could wiggle it like a tiny loose tooth.

Skin strong, but bone stronger, Lhel had said.

Tucking his chin, Tobin looked down and saw that neither the bump nor the stitching was visible. Just like before, no one could see what she’d done to him.

A wave of dizziness rolled over him as he remembered how Brother had looked, floating facedown just above him while Lhel worked. The ghost’s face was twisted with pain; tears of blood fell from his black eyes and the unhealed wound on his breast.

Dead can’t be hurt, keesa, Lhel told him, but she was wrong.

Tobin curled up against the pillow and stared miserably at the doll. All those years of hiding it, all the fear and worry, and here it lay for anyone to see.

But how had it gotten here? He’d left it behind when he’d run away from the city.

Suddenly scared without knowing why, he almost cried out for Nari, but shame choked him. He was a Royal Companion, far too old to be needing a nurse.

And what would she say about the doll? Surely she’d seen it by now. Brother showed him a vision once of how people would react if they knew, their looks of disgust. Only girls wanted dolls …

Tears filled his eyes, transforming the lamp flame into a shifting yellow star. “I’m not a girl!” he whispered.

“Yes, you are.”

And there was Brother beside the bed, even though Tobin hadn’t spoken the summoning words. The ghost’s chill presence rolled over him in waves.

“No!” Tobin covered his ears. “I know who I am.”

“I’m the boy!” Brother hissed. Then, with a mean leer, “Sister.”

“No!” Tobin shuddered and buried his face in the pillow. “No no no no!”

Gentle hands lifted him. Nari held him tight, stroking his head. “What is it, pet? What’s wrong?” She was still dressed for the day, but her brown hair was unbound over her shoulders. Brother was still there, but she didn’t seem to notice him.

Tobin clung to her for a moment, hiding his face against her shoulder the way he used to, before pride made him pull back.

“You knew,” he whispered, remembering. “Lhel told me. You always knew! Why didn’t you tell me?”

“Because I told her not to.” Iya stepped partway into the little circle of light. It left half her square, wrinkled face in shadow, but he knew her by her worn traveling gown and the thin, iron-grey braid that hung over one shoulder to her waist.

Brother knew her, too. He disappeared, but an instant later the doll flew off the chest and struck the old woman in the face. The wooden swords followed, clacking like a crane’s bill as she fended them off with an upraised hand. Then the heavy wardrobe began to shake ominously, grating across the floor in Iya’s direction.

“Stop it!” cried Tobin.

The wardrobe stopped moving and Brother reappeared by the bed, hatred crackling in the air around him as he glared at the old wizard. Iya flinched, but did not back away.

“You can see him?” asked Tobin.

“Yes. He’s been with you ever since Lhel completed the new binding.”

“Can you see him, Nari?”

She shivered. “No, thank the Light. But I can feel him.”

Tobin turned back to the wizard. “Lhel said you told her to do it! She said you wanted me to look like my brother.”

“I did what Illior required of me.” Iya settled at the foot of the bed. The light struck her full on now. She looked tired and old, yet there was hardness in her eyes that made him glad Nari was still beside him.

“It was Illior’s will,” Iya said again. “What was done was done for Skala’s sake, as much as for you. The day is coming when you must rule, Tobin, as your mother should have ruled.”

“I don’t want to!”

“I shouldn’t wonder, child.” Iya sighed and some of the hardness left her face. “You were never meant to find out the truth so young. It must have been a terrible shock, especially the way you found out.”

Tobin looked away, mortified. He’d thought the blood seeping between his legs had been the first sign of the plague. The truth had been worse.

“Even Lhel was taken by surprise. Arkoniel tells me she showed you your true face before she wove the new magic.”

“This is my true face!”

“My face!” Brother snarled.

Nari jumped and Tobin guessed even she’d heard that. He took a closer look at Brother; the ghost looked more solid than he had for a long time, almost real. It occurred to Tobin that he’d been hearing his twin’s voice out loud, too, not just a whisper in his mind like before.

“He’s rather distracting,” said Iya. “Could you send him away, please? And ask him not to make a fuss around the place this time?”

Tobin was tempted to refuse, but for Nari’s sake he whispered the words Lhel had taught him. “Blood, my blood. Flesh, my flesh. Bone, my bone.” Brother vanished like a snuffed candle and the room felt warmer.

“That’s better!” Taking up the bowl, Nari went to the brazier and dipped up the broth she had warming in a pot on the coals. “Here, get some of this into you. You’ve hardly eaten in days.”

Ignoring the spoon, Tobin took the bowl and drank from it. This was Cook’s special sickroom broth, rich with beef marrow, parsley, wine, and milk, along with the healing herbs.

He drained the bowl and Nari refilled it. Iya leaned over and retrieved the fallen doll. Propping it on her lap, she arranged its uneven arms and legs and looked down pensively at the crudely drawn face.

Tobin’s throat went tight and he lowered the bowl. How many times had he watched his mother sit just like that? Fresh tears filled his eyes. She’d made the doll to keep Brother’s spirit close to her. It had been Brother she’d seen when she looked at it, Brother she’d held and rocked and crooned to and carried with her everywhere until the day she threw herself out of the tower window.

Always Brother.

Never Tobin.

Was her angry ghost still up there?

Nari saw him shiver and hugged him close again. This time he let her.

“Illior really told you to do this to me?” he whispered.

Iya nodded sadly. “The Lightbearer spoke to me through the Oracle at Afra. You know what that is, don’t you?”

“The same Oracle that told King Thelátimos to make his daughter the first queen.”

“That’s right. And now Skala needs a queen again, one of the true blood to heal and defend the land. I promise you, one day you will understand all this.”

Nari hugged him and kissed the top of his head. “It was all to keep you safe, pet.”

The thought of her complicity stung him. Wiggling free, he scooted back against the bolsters on the far side of the bed and pulled his legs—long, sharp-shinned boy legs—up under his shirt. “But why?” He touched the scar, then broke off with a gasp of dismay. “Father’s seal and my mother’s ring! I had them on a chain …”

“I have them right here, pet. I kept them safe for you.” Nari took the chain from her apron pocket and held it out to him.

Tobin cradled the talismans in his hand. The seal, a black stone set high in a gold ring, bore the deep-carved oak tree insignia of Atyion, the great holding Tobin now owned but had never seen.

The other ring had been his mother’s bride gift from his father. The golden mounting was delicate, a circlet of tiny leaves holding an amethyst carved with a relief of his parents’ youthful profiles. He’d spent hours gazing at the portrait; he’d never seen his parents happy together, the way they looked here.

“Where did you find that?” the wizard asked softly.

“In a hole under a tree.”

“What tree?”

“A dead chestnut in the back courtyard of my mother’s house in Ero.” Tobin looked up to find her watching him closely. “The one near the summer kitchen.”

“Ah yes. That’s where Arkoniel buried your brother.”

And where my mother and Lhel dug him up again, he thought. Perhaps she lost the ring then. “Did my parents know what you did to me?”

He caught the quick, sharp look Iya shot at Nari before she answered. “Yes. They knew.”

Tobin’s heart sank. “They let you?”

“Before you were born, your father asked me to protect you. He understood the Oracle’s words and obeyed without question. I’m sure he taught you the prophecy the Oracle gave to King Thelátimos.”

“Yes.”

Iya was quiet for a moment. “It was different for your mother. She wasn’t a strong person and the birthing was very difficult. And she never got over your brother’s death.”

Tobin had to swallow hard before he could ask, “Is that why she hated me?”

“She never hated you, pet. Never!” Nari pressed a hand to her heart. “She wasn’t right in her mind, that’s all.”

“That’s enough for now,” said Iya. “Tobin, you’ve been very ill and slept the last two days away.”

“Two?” Tobin looked out the window. A slim crescent moon had guided him here; now it had waxed nearly to half. “What day is it?”

“The twenty-first of Erasin, pet. Your name day came and went while you slept,” said Nari. “I’ll tell Cook to make the honey cakes for tomorrow’s supper.”

Tobin shook his head in bewilderment, still staring at the moon. “I—I was in the forest. Who brought me to the house?”

“Tharin showed up out of nowhere with you in his arms, and Arkoniel behind him with poor Ki,” said Nari. “Scared me almost to death, just like that day your father brought your—”

“Ki?” Tobin’s head reeled as another memory struggled to the surface. In his fevered dreams Tobin had floated up into the air over Lhel’s oak and found himself looking down from a great height. He’d seen something in the woods just beyond the spring, lying on the dead leaves—“No, Ki’s safe in Ero. I was careful!”

But a cold knot of fear took root in his belly, pressing on his heart. In his dream it had been Ki lying on the ground, and Arkoniel was weeping beside him. “He brought the doll, didn’t he? That’s why he followed me.”

“Yes, pet.”

“Then it wasn’t a dream.” But why had Arkoniel been weeping?

It was a moment before he realized that people were still speaking to him. Nari was shaking him by the shoulder, looking alarmed. “Tobin, what is it? You’ve gone white!”

“Where’s Ki?” he whispered, gripping his knees hard as he braced for the answer.

“I was just telling you,” Nari said, her round face lined with new concern. “He’s asleep in your old toy room next door. With you so ill and thrashing about in your sleep, and him hurt so bad, I thought you’d rest easier apart.”

Tobin clambered across the bed, not waiting to hear more.

Iya caught him by the arm. “Wait. He’s still very ill, Tobin. He fell and hit his head. Arkoniel and Tharin have been tending him.”

He tried to pull free, but she held on. “Let him rest. Tharin has been frantic, going back and forth between your rooms like a sorrowful hound all this time. He was asleep by Ki’s bed when I passed.”

“Let me go. I promise I won’t wake them, but please, I have to see Ki!”

“Stay a moment and listen to me.” Iya was grave now. “Listen well, little prince, for what I tell you is worth your life, and theirs.”

Trembling, Tobin sank back on the edge of the bed.

Iya released him and folded her hands across the doll in her lap. “As I said, you were never meant to bear this burden so young, but here we are. Listen well and seal these words in your heart. Ki and Tharin don’t know, and they mustn’t know, about this secret of ours. Except for Arkoniel, only Lhel and Nari know the truth, and so it must remain until the time comes for you to claim your birthright.”

“Tharin doesn’t know?” Tobin’s first reaction was relief. It was Tharin, as much as his father, who’d taught him how to be a warrior.

“It was one of the great sorrows of your father’s life. He loved Tharin just as you love Ki. It broke his heart to keep such a secret from his friend, and it made the burden all that much harder to bear. But now you must do the same.”

“They’d never betray me.”

“Not willingly, of course. They’re both stubborn and stouthearted as Sakor’s bull. But wizards like your uncle’s man Niryn have ways of finding out things. Magical ways, Tobin. They don’t need torture to read a person’s innermost thoughts. If Niryn ever suspected who you really are, he’d know just whose heads to look into for the proof.”

Tobin went cold. “I think he did something like that to me the first time I met him.” He held out his left arm, showing her the birthmark. “He touched this and I got a bad, crawly feeling inside.”

Iya frowned. “Yes, that sounds right.”

“Then he knows!”

“No, Tobin, for you didn’t know yourself. Until a few days ago, all anyone would find inside your head were the thoughts of a young prince, concerned only with hawks and horses and swords. That was our intent from the start, to protect you.”

“But Brother. The doll. He would have seen that.”

“Lhel’s magic protects those thoughts. Niryn could only find them if he knew to look for them. So far, it would seem he doesn’t.”

“But now I do know. When I go back, what then?”

“You must make certain he finds no reason to touch your thoughts again. Keep the doll a secret, just as you have, and avoid Niryn as much as you can. Arkoniel and I will do whatever we can to protect you. In fact, I think it may be time for me to be seen with my patron’s son again.”

“You’ll come back to Ero with me?”

She smiled and patted his shoulder. “Yes. Now go see your friends.”

The corridor was cold but Tobin hardly noticed. Ki’s door stood slightly ajar, casting a thin sliver of light out across the rushes. Tobin slipped inside.

Ki was asleep in an old high-sided bed, tucked up to the chin with counterpanes and quilts. His eyes were closed and even in the warm glow of the night lamp, he looked very pale. There were dark circles around his eyes and a linen bandage wrapped around his head.