Полная версия

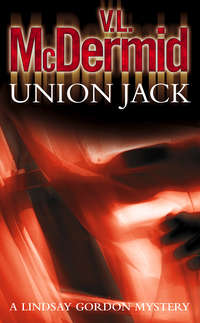

Union Jack

V.L. McDERMID

Union Jack

Contents

Title Page Note To Readers Prologue: Mid-Atlantic, April 1993 Part One: Blackpool, April 1984 Chapter One Chapter Two Chapter Three Chapter Four Part Two: Sheffield, April 1993 Chapter One Chapter Two Chapter Three Chapter Four Chapter Five Chapter Six Chapter Seven Chapter Eight Chapter Nine Chapter Ten Chapter Eleven Chapter Twelve Chapter Thirteen Chapter Fourteen Chapter Fifteen Chapter Sixteen Chapter Seventeen Epilogue About the Author By The Same Author Copyright About the Publisher

NOTE TO READERS

For the best part of a decade, I was an active member of the National Union of Journalists, holding a variety of posts at local and national level. During that time, I was elected as one of Manchester’s representatives for several Annual Delegate Meetings. My experiences in the union provided me with the knowledge that underpins this book. But I should emphasise that neither the events nor the characters in Union Jack are even remotely based in fact. The truth is that, just as thousands of delegates to union conferences have told their spouses, we spent our time in earnest debate, working tirelessly to improve the lot of our members. If we looked worn out by the time we returned home, it was simply because of the energy we had expended in passionate argument. Would I lie to you?

On a more serious note, I’d like to thank the many fellow trade unionists who became friends over those years for their help, conscious and unconscious, in the preparation of this book. These include Sue Jackson and Kerttu Kinsler, Diana Muir, Scarlett MccGwire, Gina Weissand, Malcolm Pain, Eugenie Verney, Nancy Jaeger, Pauline Norris, Sally Gilbert, Colin Bourne, Tim Gopsill and Dick Oliver. Most of all, I want to thank BB, who gave me inspiration when I needed it most.

Any resemblance to real people, living or dead, is purely in the mind of the reader.

For BB: Good things come to she who waits

PROLOGUE

Mid-Atlantic, April 1993

‘I could murder some proper orange juice,’ Lindsay Gordon grumbled, wrinkling her nose in disgust at the plastic cup of juice on her airline breakfast tray. She sipped suspiciously. It managed to be both sharp and sickly at the same time. ‘You know, something that tastes like it once met an orange. This stuff hasn’t even been shown a photograph.’

‘You’d better get used to it,’ Sophie Hartley said, peeling the lid back from her own cup and knocking back the liquid. She winced. ‘Not that it’ll be easy. Think you can survive two weeks without freshly squeezed juice?’

Lindsay shrugged. ‘Who knows? If it was only the juice …’

Sophie snorted. ‘Hark at it. This is the woman whose idea of healthy eating used to be adding a tin of baked beans to bacon, sausage, egg and chips. Listen, Gordon, you can’t come the California health freak with me. I can remember when the nearest thing to fruit juice in your flat was elderberry wine.’

‘Huh,’ Lindsay grunted. ‘Don’t get superior with me just because you used to eat your vegetables raw even though you could afford the gas bill. Anyway, I’m not a California health freak. It would take more than a bunch of New Age born-again hippies to change Lindsay Gordon, let me tell you. First thing I’m going to do when I get off this plane is head for a chip shop and get tore in to a fish supper.’

Sophie shook her head, smiling. ‘You can’t fool me, Gordon. Three years in California and you’re working out, eating salad twice a day, swallowing vitamins like Smarties, even wearing jumpers made from reclaimed wool. You’re a California girl now, like it or not.’

Lindsay shuddered. ‘Rubbish. The odd jog up the beach, that’s all, and I was doing that long before America.’

Sophie grinned affectionately at her lover, and wisely held her peace.

‘Ladies and gentlemen, we are now commencing our descent into Glasgow Airport. Please return to your seats and fasten your seat-belts. Please extinguish all smoking materials …’

‘Looking forward to it?’

Lindsay shrugged. ‘Yes and no. I’ve been out of the game a long time. I’m not sure I even know what the issues are for trade unionists in the UK any longer.’ Sophie squeezed her hand. ‘It’ll be just fine.’

Lindsay smiled. ‘Shouldn’t it be me saying that to you, Dr Hartley? You’re the one delivering a keynote paper at an international conference.’

‘Play your cards right at this media conference, and you’ll be a doctor soon too. Pick the right brains for your thesis, and they’ll be begging you to accept a Ph. D.’

Lindsay pulled a face. ‘I’m not so sure. I’m not even sure I’ve still got the old interview techniques. Teaching journalism’s a long way away from practising it.’

‘You’ll be fine,’ Sophie assured her. ‘You’ll soon adapt to being back in the old routine. After all, you’ll be among friends.’

Lindsay gave a shout of laughter that turned heads three rows away. ‘Among friends? At a union conference? Soph, I’d feel safer in the lion’s cage half an hour before feeding time. One thing I’ll never be able to forget is the aggro level of Journalists’ Union conferences. You’d think we were arguing over life and death, not politics. I can’t imagine that amalgamating with the broadcasting and printing unions has made the atmosphere any friendlier. It’s not culture shock I’m afraid of – it’s being trapped in a time warp.’

PART ONE

Blackpool, April 1984

1

‘Delegates are discouraged from travelling to conference by private car, and mileage expenses will only be paid in extraordinary circumstances. This is because, firstly, the union has negotiated a bulk-rate discount with British Rail; secondly, there are limited car-parking facilities available at the hotels we are using; and thirdly, the chances are that when driving home on Friday afternoon at the end of conference you will still be over the limit from Thursday night’s excesses. It is not the union’s policy to encourage members to lose their licences due to drink-driving.’

from ‘Advice for New Delegates’, a Standing Orders Sub-Committee booklet.

‘This traffic’s murder,’ Ian Ross complained, easing the car forward another couple of feet. ‘Look at it,’ he added, waving his arm at the sea of hot metal that surrounded them.

Lindsay Gordon did as she was told, for once. In the distance, Blackpool Tower’s iron tracery stood outlined against the skyline like an Eiffel Tower souvenir on a mantelpiece. ‘Only the Journalists’ Union could organise a conference that involves 400 delegates travelling to the biggest holiday resort in the North of England on Easter Monday,’ he remarked caustically. ‘Bloody Blackpool. It’s taken us an hour to travel six miles. By the time we get to the hotel, the conference will be over and it’ll be time to come home. I bet you wish you’d taken the train, don’t you? You could have been walking along the prom by now, eating candy-floss and wearing a kiss-me-quick hat.’ Ian glanced sideways and saw the bleak look on Lindsay’s face. He sighed. ‘Sorry, love. I wasn’t thinking.’

‘It’s okay. I’ve told you. You don’t have to treat me like a piece of porcelain.’ An awkward silence filled the car. Lindsay patted Ian’s hand and repeated, ‘It’s okay.’

Ian nodded. ‘Time for The World At One. Shall I stick the radio on?’

‘Sure.’ Lindsay leaned back in her seat and tried to let the radio obliterate her thoughts.

‘A hundred arrests are made in Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire in the worst violence of the miners’ strike so far. Police clash with miners outside several collieries, and NUM leader Arthur Scargill accuses officers of intimidation. Anti-apartheid protesters besiege the Home Office after last week’s decision to grant British citizenship to the South African runner Zola Budd. And Senator Gary Hart fights to continue his campaign against Walter Mondale for the Democratic nomination in the US Presidential race.’ The announcer’s voice droned on, fleshing out the day’s headlines. But Lindsay’s mind was already miles away.

It had been a mistake to come. She had been too easily persuaded by Ian. She wasn’t ready for this. It was hard enough coping with the day to day routine of life, a routine that was manageable precisely because it was familiar, because her mind could drift off into free-fall while she gave the appearance of being in touch with what was going on around her. But to plunge into something so strange and challenging as her first national union conference was madness. It had been bad enough just reading about conference. She’d had to give up on the ‘Advice for New Delegates’ booklet half-way through, her head spinning with such bizarre and diverse items as ‘taking a motion seriatim’ and ‘compositing sessions’. How on earth was she going to wrestle with the real thing with only half her brain functioning?

Ian had meant well, she knew that. He was a news sub-editor on the tabloid newspaper where Lindsay, at twenty-five, was the most junior staff reporter. When she had started to show an interest in the union, speaking up at the meetings of the Daily Nation’s office chapel, it was Ian who had taken the time to explain to her how their union functioned in national newspapers. He had spent the weary, slow hours of several night-shifts outlining the organisation and the internal politics that governed the union far more than the rule book.

Lindsay, who had learned about socialism and solidarity from her fisherman father as soon as she could grasp the concepts, was bemused by the schisms and hierarchies of what she had naïvely imagined would be an organisation unified by a common aim. It didn’t take her long to decide that the entrenched power of the national newspaper chapels generated its own inbuilt conservatism, and that the real arenas for potential change within the union lay elsewhere. The radical concepts of feminism and genuinely representative democracy that were dear to her were clearly never going to find fertile soil in this sector of the industry. Here traditions had provided the hacks with a comfort zone where they could all be good old boys together, and to hell with troublesome dykes, poofs, women, jungle bunnies and cripples.

That complacency placed the Daily Nation’s chapel high on Lindsay’s list of institutions in need of a short, sharp shock. But before she could do anything about it, she’d been overtaken by events that had rendered the Journalists’ Union as significant as a speck of dust in a rainstorm. In the weeks that had followed, Ian had tried to take her mind off her own problems by involving her in the JU, but she couldn’t have cared less. When he’d tried to jog her out of her misery by arranging for her to be elected as one of the Fleet Street Branch’s dozen delegates to the Annual Delegate Conference, she’d simply let herself be carried along with the tide.

Frances. It would all be all right if Frances was still with her. They could have laughed about these codes and rituals that made the Freemasons sound rational. Frances would have worked through the agenda with her, discussing the 246 motions. She and Frances would have snuggled up in bed together, giggling over the strange injunctions in the advice booklet. And Lindsay would have had the anticipation of nightly phone calls to keep her going through the difficulties of the days. She wouldn’t be going through this state of semi-panic that seemed to grip her all the time.

But Frances wasn’t ever going to be with her again. Lindsay knew that getting used to that idea was the hardest thing she’d ever have to face. No more Frances at the breakfast table, frowning over The Times’ law reports, or, if she was due in court, taking a last-minute look through her brief for the day. No more meeting for a snatched lunchtime drink in one of the dozens of pubs between the Daily Nation’s Fleet Street offices and the law courts. No more sitting on the press benches, watching Frances on her feet defending her client, face stern beneath the barrister’s absurd curly wig. No more coming home from a hard day’s news reporting to sit on the side of the bath sipping dry white wine while Frances luxuriated in the suds and they swapped stories. No more Frances.

It wasn’t self-pity. At least, she didn’t think it was. It was the difficulty of adjusting to absence. Someone who had been there was no longer around. And it had left a Frances-shaped hole in her life that sometimes felt as if it would engulf her and drain the very life from her. That was the worst feeling of all. The pain of loss, a physical stab in the chest that sometimes made her gasp, that was bad enough. But the hollowness, that was the worst.

With a start, Lindsay realised that Ian was speaking. ‘I’m sorry?’ she said.

‘That lot,’ Ian said, gesturing with his thumb at the radio. ‘Bloody coppers on their horses, acting like the Cossack army. The writing’s on the wall, Lindsay. This government isn’t going to stand for any sort of trade union activity, you mark my words.’ When he was angry, Ian’s Salford accent always reemerged from the southern patina it had acquired over ten years of working in London. The thickness of his accent was a rough guide to the level of his anger. Right now, he sounded like a refugee from Coronation Street.

‘Before Thatcher’s finished with us, she’ll have the Combination Acts back on the statute book. A few years from now, we’ll all be arrested for conspiracy if we try to hold a chapel meeting,’ he continued.

Lindsay sighed and reached for her cigarettes. ‘It’s so short-sighted,’ she said. ‘The government’s always telling us about the wonderful economic success of the Germans, about how they don’t have strikes. It never seems to occur to them that that’s because the German bosses consult the workforce before they embark on anything that affects them. But this government doesn’t want consultation, they want confrontation.’

‘Yeah, but only on their terms. As soon as journalists try to confront them with the hard questions about what’s happening in this country, they slam the shutters down. Look at the hassle they’ve been giving the BBC!’ Ian exploded. Then, suddenly, he fell silent, mouth clamped shut, the muscles standing out against the sharp line of his jaw.

‘I suppose it’s keeping Laura busy,’ Lindsay said uncertainly, assuming Ian’s silence was somehow connected to his lover, Laura Craig. Laura was employed by the JU to organise union activities in the broadcasting sector. The government’s recent ham-fisted efforts at censorship and control had given her several thorny problems to deal with. Lindsay had often heard Ian complain that he hardly saw her these days.

‘I suppose it is,’ he said coldly. A slight gap in the traffic opened up, and Ian accelerated jerkily to take advantage of it. As he drew close to the car in front, he braked sharply enough to throw them both against their seat-belts. ‘Sorry,’ he muttered, running a hand through his thick, straight salt-and-pepper hair.

‘Problems?’ Lindsay asked with sinking heart. She had enough on her own plate without having to bother with someone else’s hard time, she thought bitterly. But Ian was a friend. She felt obliged to give him the opening.

‘You could say that.’ The news programme ended, and the jaunty signature tune of The Archers jangled in their ears. Ian’s hand shot out and twisted the volume knob as far down as it would go. ‘She’s moved out,’ he said softly in the sudden peace. His grey eyes stared straight ahead.

Lindsay tried out various responses in her head. ‘When?’ ‘Why?’ ‘I never liked her anyway.’ ‘Is there … someone else?’ She settled for, ‘Oh, Ian. Poor you. What happened?’ It seemed to combine solicitude with support. Please God, he wouldn’t feel like telling her.

At first, it seemed as if Lindsay’s prayer had been answered. Ian said nothing, simply concentrating on the road and the car in front. They started moving again, and, miraculously, whatever had been clogging the traffic vanished. Within minutes, the engine was in third gear, the tower was growing taller and Ian had become talkative. ‘You know how you think you know someone? You feel comfortable with them? You could see yourself spending the rest of your life with them? Well, that’s how it was with me and Laura,’ he said.

And me and Frances, Lindsay echoed mentally. ‘You seemed to get on so well together,’ she said.

Ian gave a hollow laugh. ‘Just shows how blind you can be, doesn’t it? What a mug.’ He took a deep breath, then broke into a fit of coughing. As he recovered, his hand went out automatically to the glove box. He opened it and took out a blue plastic tube with an angled end which he put in his mouth. Lindsay tried not to look as if she was paying attention as he used the inhaler and chucked it back in the glove box.

‘Is my cigarette bothering you?’ she asked.

Ian shook his head, holding his breath. He let the air out in a controlled gasp. ‘Cigarette smoke doesn’t set my asthma off. Now, if you were wearing Rive Gauche or you had a dog at home, I’d have to strap you to the roof-rack. Poor Laura could never treat herself to a new perfume without consulting me first. Oh well, that’s one thing she won’t have to worry about any more.’

The bitterness in his tone shocked Lindsay. It seemed so alien from Ian, that most gentle of men. It was hard to square with the devoted adoration he’d always displayed when he’d talked about Laura in the past. He was one of those men who carry photographs of their lovers and find the most tenuous excuses to pull them out of their wallets and display them. Long before she’d ever met Laura in the flesh, Lindsay had seen Laura in Greece, Laura in Scotland, Laura on horseback, Laura in a sailing dinghy, Laura in evening dress and Laura asleep.

‘When did all this happen? You haven’t mentioned it at work,’ Lindsay said.

‘I could do without the snide jokes. Worse than that, the pity,’ Ian said. He wasn’t misjudging their colleagues, Lindsay thought sadly. ‘I threw her out three weeks ago last Saturday,’ he added.

He threw her out. It took a moment for Lindsay to grasp what Ian had said. Given his devotion, it could only mean Laura had been seeing someone else and Ian had found out. With her looks, and the force of her personality, she couldn’t have been short of other offers. And although you’d go a long way before you found a kinder man than Ian, not even his own mother would have described his sharp features, beaky nose and long, skinny body as handsome. Lindsay had occasionally wondered what had attracted them to each other in the first place. Laura Craig was a woman who liked beautiful things, if her clothes and jewellery were anything to go by. But Ian wasn’t given to superficial judgements so Lindsay had always thought that must mean that there was more to Laura than the stylish, hard-edged exterior she presented to the world. She flicked a sidelong glance at Ian. His mouth was clamped shut, his lips a thin line. Clearly, he didn’t want to dissect what had happened. Lindsay breathed a silent sigh of relief. The sordid details of Laura’s infidelity she could do without.

The car had slowed again as they reached the centre of the town. The pavements were thronged with day-trippers, enjoying the brief moments of sunshine that escaped from the drift of cloud. Like any British Bank Holiday crowd, people were dressed for extremes. It was either cap-sleeved T-shirts or macs as far as the eye could see.

‘The street map’s in the glove box,’ Ian told her as they emerged on the Golden Mile in all its tacky glory. Ian turned north, the tram-lines and the sea wall to the left, the endless string of cheap hotels, amusement arcades, Gifte Shoppes, pubs and fast food outlets to their right.

Lindsay studied the photostat sheet that had been enclosed in their delegates’ fact pack. Efficient as ever, Ian had marked the Princess Alice hotel with a red cross. Lindsay checked the name of the next side street they passed.

‘About another mile to go, I’d say,’ she estimated. The Golden Mile’s attractions petered out, giving way to more hotels, boarding houses, and bed and breakfast establishments. ‘There it is,’ Lindsay said at last, pointing to a huge red brick edifice whose five storeys looked forbiddingly over the grey Irish Sea. ‘It looks more like a Victorian asylum than a hotel.’

‘Couldn’t be more appropriate for a JU conference, as you’ll discover soon enough,’ Ian replied. ‘And as you’ve probably noticed from the map, it’s conveniently situated only two miles from the conference centre itself. Bloody hell,’ he exclaimed as he pulled off the road on the forecourt. ‘They weren’t joking when they said there was limited car-parking, were they?’ The whole area in front of the hotel was asphalted over to provide spaces for cars, but it had clearly never been a majestic sweep of lawn to start with. Ian inched forward, looking for a space.

‘Over there. Right by the wall, look, someone’s pulling out,’ Lindsay said. Ian shot forward and squeezed his Ford Escort into the narrow gap.

‘Well spotted,’ he said, opening his door and getting out. He raised his arms in a long stretch and yawned. Then he opened his eyes and froze. ‘Jesus Christ. What the hell is she playing at?’ he whispered.

Lindsay turned to look at the woman who had caught his eye. Laura Craig strode up the short drive of the hotel, wavy brown hair lacquered solid against the whipping westerly wind. But Laura wasn’t alone.

2

‘Delegates are reminded that their duty is to follow debates and cast votes on behalf of their members. However appealing the bars, cafés, fringe meetings, gossip sessions and members of your gender of choice, the conference hall is where you should be. We know it can be boring; we even know of delegates who prefer hanging around at Standing Orders Sub-Committee rather than staying in the hall. In the interests of preserving your SOS members’ sanity, please do not attend our sessions unless you are entitled to a voice [see S05(b) (ii) and Footnote xiv]. Flattered though we are to be the centre of delegates’ attention, this does not help the smooth flow of conference order papers!’

from ‘Advice for New Delegates’, a Standing Orders Sub-Committee booklet.

Lindsay sighed. In spite of sitting up past midnight ploughing through the final conference agenda, with all its proposed amendments, she still hadn’t a clue what this discussion was about. She was sitting on the margin of a group of a dozen delegates arguing with Brian Robinson, the Standing Orders Sub-Committee member responsible for preparing the industrial relations order-paper.

As Brian wiped his perspiring pink face with a flamboyant silk handkerchief, Ian leaned over and said quietly to Lindsay, ‘With it so far?’

‘Not really,’ she admitted. ‘What exactly are they arguing about?’

‘Manchester Branch and Darlington Branch have both submitted motions on the same broad topic, and Brian wants to amalgamate them into one composite motion. Now they’re each arguing about what they think their motion really said. Brian has to make sure they end up with something that includes all of the key points in the two original motions, without incorporating anything that wasn’t there to start with.’

Lindsay shook her head. ‘I can’t believe grownups think this is a reasonable way to spend their time,’ she muttered. ‘It’s like an Oxford tutorial without the relevance to real life.’ She tried to concentrate on the obscure negotiation that continued like some quaint ritual dance whose meaning was lost in the sands of time. But it was no use. There wasn’t enough meat in the argument to occupy her mind, and her grief kept butting in like an anarchist at the trooping of the colour. After another half hour, she leaned towards Ian and muttered, ‘I’m going to get some air.’