Полная версия

The Maze

‘THE DETECTIVE STORY CLUB is a clearing house for the best detective and mystery stories chosen for you by a select committee of experts. Only the most ingenious crime stories will be published under the THE DETECTIVE STORY CLUB imprint. A special distinguishing stamp appears on the wrapper and title page of every THE DETECTIVE STORY CLUB book—the Man with the Gun. Always look for the Man with the Gun when buying a Crime book.’

Wm. Collins Sons & Co. Ltd., 1929

Now the Man with the Gun is back in this series of COLLINS CRIME CLUB reprints, and with him the chance to experience the classic books that influenced the Golden Age of crime fiction.

Copyright

COLLINS CRIME CLUB

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published for The Crime Club by W. Collins Sons & Co. Ltd 1932

Copyright © Estate of Philip MacDonald 1932

Introduction © Estate of Julian Symons 1980

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008216375

Ebook Edition © December 2016 ISBN: 9780008216382

Version: 2016-11-23

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Introduction

Preface

Part One

Part Two

Chapter I

Chapter II

Chapter III

Chapter IV

Chapter V

Chapter VI

Chapter VII

Chapter VIII

Chapter IX

Chapter X

Chapter XI

Chapter XII

Chapter XIII

Chapter XIV

Chapter XV

Chapter XVI

Chapter XVII

Part Three

Part Four

Appendix

I

II

III

Enclosure

The Detective Story Club

About the Publisher

INTRODUCTION

THE idea of the crime story in which the solution should be the result of perfectly rational deductions from given facts—an exercise in ratiocination, as Poe called it—was one that preoccupied writers in the ’twenties and early ’thirties, when the crime story was coming of age. It was this dream that the early Ellery Queen books tried to fulfil with their ‘Challenge to the Reader’ three-quarters of the way through; that was at the heart of John Dickson Carr’s locked room mysteries; that was approached at times by writers as various as Anthony Berkeley, Agatha Christie and C. Daly King.

The Maze, which was published in 1932, is Philip MacDonald’s contribution to this conception of the totally logical puzzle. It is, he says, ‘An Exercise in Detection’, and he claims that you are provided with all the evidence on which his detective, Anthony Gethryn, works, and from which he deduces the truth. He says more than this:

In this book I have striven to be absolutely fair to the reader. There is nothing—nothing at all—for the detective that the reader has not had. More, the reader has had his information in exactly the same form as the detective—that is, the verbatim report of evidence and question.

This is a fair story.

Does Philip MacDonald claim too much? I don’t think so. The facts are clearly laid out, and Gethryn’s deductions are admirably logical, beginning with what he calls oddities, and moving from one of these to another to build a case which—if we had spotted the oddities—we could have formulated ourselves. Upon the basis of logic, Gethryn’s case is not to be denied, although, as he acknowledges, it is a structure that can be demonstrated but not proved. A perfect crime story, then? Why no, for The Maze has the weakness inherent in that desire for a wholly logical crime story, the weakness that we take an interest in the solution to the crime but not in the people who may have committed it. Yet in its time The Maze was a notable and underrated crime story, and it remains one of the truly original experiments of the period.

Today Philip MacDonald is almost forgotten, but he and his detective Anthony Gethryn were celebrated figures in the years between the Wars. The Rasp, the first crime story he published under his own name, was an immediate success, and The Noose (he had a taste for single word titles) was the first Crime Club choice in 1930. The Evening Standard bought the serial rights, MacDonald’s sales quadrupled, and within a year the Crime Club had 200,000 members. MacDonald continued to produce successful books under several pseudonyms and a number of them were experimental in one way or another. Three of the best were Rynox, Murder Gone Mad, and X v Rex, the last of which was written under the pseudonym of Martin Porlock. The construction of these books is sometimes careless, but they all contain extremely ingenious ideas, and the desire to do something new is always apparent. Then, in the early ’thirties, MacDonald was invited to Hollywood by RKO Pictures, became a scriptwriter, and wrote little more except for the screen, although he produced in 1952 a collection of short stories called Fingers of Fear, some of which show his characteristic cleverness. As a crime novelist, however, MacDonald’s career really ended in the ’thirties. It is not surprising that he has been forgotten.

The exuberant and indefatigable American crime buff Dilys Winn recently discovered MacDonald living in the Motion Picture Retirement Home near Malibu, and talked to him about his career. She found him inclined to deprecate the books that had made his name: ‘They’re all a bit dated, aren’t they?’ The Noose he thought ‘awfully old-fashioned’, and he would probably have said the same about The Maze. Dilys Winn found conversation difficult, and from her account of the interview one gets the impression that the time when MacDonald wrote crime stories was for him an ocean and a different life away. He belonged even in appearance to that different life. For the interview he sported an ascot, carried a silver-handled cane, and had his hair precisely parted and slicked down with pomade.

He said firmly that he was born in 1900, but this would mean that his first book Ambrotox and Limping Dick, written in collaboration with his father, was published when he was twenty years old. He thought that his best book was Patrol, which is not a crime story, rated his short stories higher than his novels, and expressed his aversion to literary company. ‘Two writers in one room is too many.’

I think it must be acknowledged that The Maze, like its author, is a period piece, but it is one that must give pleasure to any reader who likes to solve a puzzle and to pit his own wits against those of the author’s detective. And there is another reason why I hope that Philip MacDonald will be pleased to see the book republished. The most wistful thing he said in the course of the interview was that the Home’s library did not contain ‘one tiny word, not one, of mine.’ At least The Maze can now find its proper place upon the shelves.

JULIAN SYMONS

1980

PREFACE

I HAVE given this book the subtitle of ‘An Exercise in Detection’.

I have used the word ‘exercise’ deliberately; I mean it to be an exercise not only upon my part, but upon the part of any reader who may have the tenacity to get through it. In Parts Two, Three and Four of the book—the actual evidence of the witnesses upon the first time of their calling and the summing up of the Coroner—is contained all the information upon which Gethryn has to work. In other words, you, the reader, and he, the detective, are upon an equal footing. You know just as much as and no more than he knows. He knows just as much as and no more than you. He finds out: could you have found out without his help?

I should like to emphasise that although, for the sake of ‘balance’ and of avoiding tediousness, part of the evidence (that is, the re-examination and re-examination of the witnesses) has been omitted, none of this evidence was anything except repetitive. Gethryn, in fact, was not supplied with this repetitive evidence, as is shown by the note to him from Lucas. What Gethryn had is what you have. From what you have he made his deductions.

I have frequently been annoyed—as any reader of the analytical type of detective fiction must have been annoyed—by books in which the detective holds an unfair advantage over the reader in that he has opportunities which the reader cannot share. He may, for instance, in Chapter II ‘dash up to London and spend two hours there.’ And then the reader, not having been allowed to see what the detective did during those two hours in London, is at a disadvantage. Again, in Chapter XVII, the detective may suddenly, in a foully offhand and altogether offensive manner, ‘pick some small object off the ground’ which he puts in his waistcoat pocket and doesn’t say anything more about until Chapter XXIII, when it forms the basis upon which his whole case is founded. Again the reader has been subjected to the most dastardly unfair play!

In this book I have striven to be absolutely fair to the reader. There is nothing—nothing at all—for the detective that the reader has not had. More, the reader has had his information in exactly the same form as the detective—that is, the verbatim report of evidence and question.

This is a fair story. If you get the right answer—not merely a ‘guessed’ answer, but an answer for which you are prepared to put forward reasons—then you are as good at this job as A. R. Gethryn. If you don’t, you are not. In either case I think you should be satisfied—unless, of course, you find the whole business too impossibly easy, in which case you ought—if you are not indeed already one—to become a really big noise at Scotland Yard.

PHILIP MACDONALD

1932

PART ONE

LETTER DATED 14th JULY, 193– FROM ASSISTANT COMMISSIONER SIR EGBERT LUCAS, C.I.D., TO LIEUT.-COL. ANTHONY RUTHVEN GETHRYN

SCOTLAND YARD,

14th July, 193–

MY DEAR GETHRYN,

It is with a good deal of diffidence that I approach you, remembering our conversation before you left England for this holiday. You said that upon no account were you going to ‘inaugurate, contemplate or elucidate crime or any minor or major misdemeanours!’ You also said, I believe, that you were not going to read any English newspapers while you were out of England. Be that as it may, I am worrying you. I would like you to understand, however, that the fact that I am worrying you is due only partly to my own inclination. Charters himself, Pike and Jordan—and, this morning, even Bunter—have all brought pressure to bear upon me. I suggested to Charters that if he wanted to worry you he should do it himself. But he wasn’t having any. And so, as usual, I’m left to do the dirty work. It may be very pleasant to be the First Commissioner of Police. It’s certainly very pleasant to be an ordinary Police Constable. But who would be an Assistant Commissioner?

I feel that I’m taking an unconscionably long time to get down to brass tacks. That’s probably due to the fact that I’m dictating this letter and also to the fact that I’m nervous about its reception when I remember my promise to you of a few weeks back. However, here goes:

Since you’ve been away there has happened—near Kensington Gore of all unlikely places!—a case which is the most extraordinary within my fairly long experience and also, I am told, within the thirty-five years’ experience of old Jordan. Certainly in all my knowledge—official and private, actual and literary—there has never been anything quite like it.

In Kensington, on the night of the 11-12th July, a man was killed. He met his death, abiding by all the canons of the best ‘mystery fiction’ in his study. It is certain beyond all possibility of doubt that he was murdered. It also seems certain beyond all possibility of doubt that he met his death at the hands of a person who was, for the time being at least, resident beneath his roof. There were, besides the murdered man, ten people sleeping in the house on the night of his death. One of them must surely have done it! But it has proved quite impossible for us to fix upon this one person. This doesn’t look good for the police. Moreover, it is intensely annoying to any person of intelligence. Having been with the case since it began a few weeks ago—which seem like ten years—I can most earnestly vouch for this. I felt—and still feel—as I used to feel as a child when I went to Maskelyne and Cook’s. I can still feel the appalling, stifling, impotent irritation of the Irish peasant priest faced with the question: ‘If God is omnipotent, can He make a stone so heavy that He can’t lift it?’

What we want you to do is to look at the papers we have on the case and just see if you can spot anything which we may have overlooked. I think it is hopeless. But I also think—knowing you as I do—that the chance is worth taking even at the risk of drawing down upon myself a sulphurous rebuke.

I had originally intended to write this letter and ask your permission to send you the papers (verbatim report of inquest, etc.). On maturer thought, however, I have decided to enclose copies of these herewith, for it has struck me that your answer to a request as to whether one might send papers would be useless, whereas your reaction to a bundle of papers might well be one of sufficient curiosity at least to make you read them through. And if you do read them through I am convinced that the sheer complexity of an apparently simple business will decoy you into spending thought upon it—and that, after all, is what we really want.

With all my respects to your wife and admiration to your small son,

Yours very sincerely,

E. LUCAS

PART TWO

VERBATIM REPORT OF EVIDENCE GIVEN AT THE CORONER’S INQUEST HELD UPON THE BODY OF MAXWELL BRUNTON, DECEASED (1st DAY)

I

L.I. 84833 SERGEANT GEORGE CRAWLEY,

METROPOLITAN POLICE

WHAT is your full name?

George Crawley.

Now, will you please take the oath.

I swear by Almighty God that what I shall say in evidence in this Court shall be the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth.

You are a sergeant in the Metropolitan Police Force?

Yes. L.I. 84833. Full-Sergeant George Crawley.

Would you please tell the Court, Sergeant, the circumstances under which you were called to 44 Rajah Gardens in the early morning of Thursday last, the twelfth of July.

I was going round the beats. I had just spoken to the constable in charge of the Baroness Gardens—Stukeley Road beat, and was walking on to my next point, going through the northern end of Rajah Gardens, when a man ran out of one of the houses and hailed me. Time 2.40 a.m. He told me he was a servant at Number 44, Mr Maxwell Brunton’s. He was agitated and made a rambling statement which I had some difficulty in following. He was dressed in a dressing gown and slippers. On the doorstep there was a gentleman in evening dress. He said he was Mr Brunton’s secretary, and he himself had just made the discovery that Mr Brunton was dead in his study. I asked to see the room, and this gentleman, Mr Harrison, said he would take me up. There were a number of the other inmates of the house gathered round in the hall. I asked them to stay where they were until sent for. I also sent the manservant, Jennings, to fetch the constable on the beat and told him to let me know when he arrived.

I then mounted the stairs with Mr Harrison, who took me to the deceased’s study. This is a room at the western side of the house. It is a room which has been built out over the area which lies below, beside the passage leading through from the street to the gardens belonging to the block. There is only one door to this study. This door faces you as you go down the corridor after turning left from the landing …

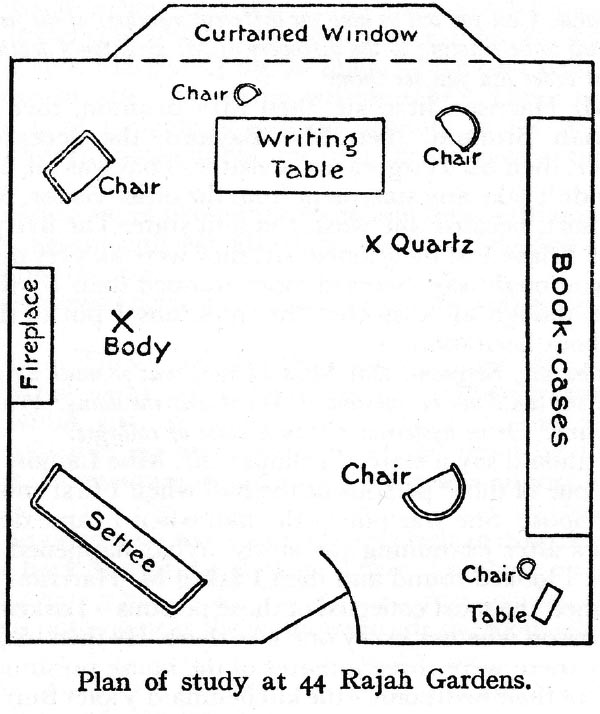

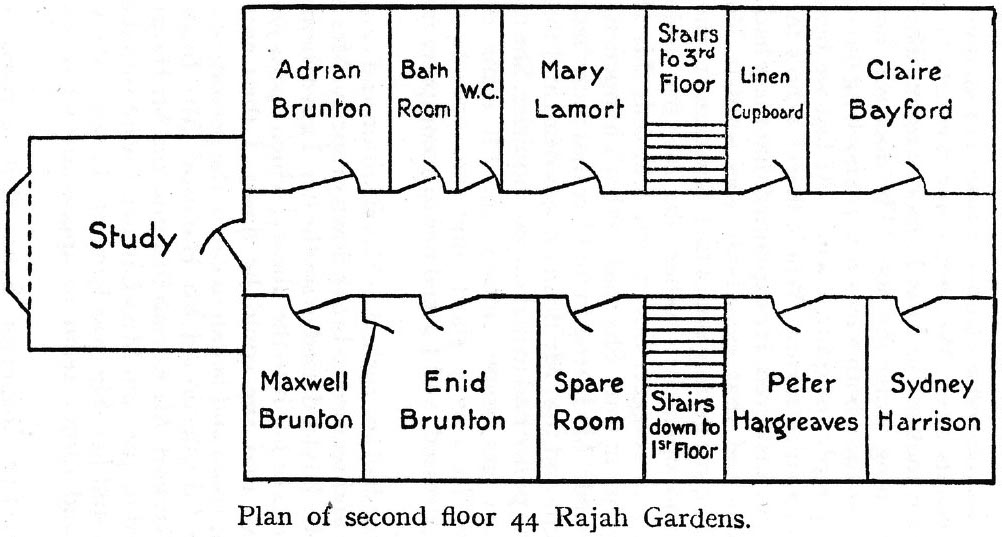

One moment, Sergeant. Have the police any plans of this house? Perhaps the jury might like to see them.

Yes, sir. One was put in with the other Police papers. I think it was marked Number 6 on the docket.

Ah! … Number 6 you said. Yes! Yes! Stupid of me … Gentlemen, you may like to pass this plan round among yourselves.

. . . . . .

Thank you. I hope the plan is clear to you all.

. . . . . .

Excellent! Now, Sergeant, if you’ll continue …

Very good, sir. I entered the study and found the body of the deceased lying on the hearth-rug. With the police papers, sir, there’s a plan of the room showing the exact position of the body. The head was pointing toward the centre of the bay window and the feet toward the door. Deceased was dead. I judged life to have been extinct for quite a while. The only injury I could find on examination was to the right eye. This had been penetrated, the object which effected the injury having pierced apparently right through to the brain. There was a good deal of blood. Lying by the body was a large lump of mineral which I took to be gold quartz. That mineral lump is among your exhibits, sir. I found the long spur which projects from one end of it to be covered with blood. The lump was lying at some distance from the body at the spot marked Q on the plan which you will see is close by the foot of the writing-table. There were no signs of struggle or any disturbance in the room. All the furniture, papers, etc., on the desk were quite tidy.

I made a rapid plan of the room and then went downstairs again with Mr Harrison, locking the door and retaining the key.

One moment, Sergeant. Did you examine the windows of the study?

Yes, sir. They were all open. You will remember it had been a hot night, sir. I examined the windows particularly with a view to ascertaining whether it would have been possible for anyone to leave the room by that means. In my opinion, sir, such a thing was impossible. The room is on the second story of the house, and being built on extra, as it has, there is simply a clean drop down to the back area of the kitchen. There is nothing on the wall for foot or hand-hold. There are no trees near by, and there is nothing near the windows inside the room which could have been used to sling a rope round.

I see. Thank you, Sergeant. You were saying that you went downstairs with Mr Harrison.

Yes, sir. When we got to the foot of the stairs I found that the manservant had returned with a constable. I placed the constable on duty outside the door and then telephoned to my headquarters and reported. I was given instructions to take preliminary statements from the members of the house, and did so. Those statements are, I believe, together with the other statements taken later, in the police papers which you have got, sir.

I see … Now, Sergeant, one or two questions. You were the first outside person to enter this house, and your impressions may be of value. Can you tell us how the different members of the family seemed to be reacting to the discovery of Mr Brunton’s death? In what order did you see them?

Mr Harrison first, sir, then Mrs Brunton, then Mr Adrian Brunton, then Mrs Bayford, the deceased’s sister, then Mr Hargreaves, a visitor. That was all, sir. I couldn’t take any statement from the other visitor, Miss Lamort, because she wasn’t in a fit state. The five persons I’ve just mentioned, sir, they were all very quiet, as you might say. Seemed more stunned than anything else, though all answered the questions I put to them without hesitation.

You say, Sergeant, that Miss Lamort was so much agitated that she could not be questioned. What was she doing? Was she fainting? Or in hysterics? Or in a state of collapse?

I should say a state of collapse, sir. Miss Lamort was not one of those persons in the hall when I first entered the house. She was not in the hall when I came downstairs after examining the study. What happened was this: I looked round and then I asked Mr Harrison—he seemed the most collected of those persons—I asked Mr Harrison whether everyone was there. He then told me that there were three inmates of the house presumably still in their bedrooms—the kitchenmaid Violet Burrage, Mrs Brunton’s maid Jinette Bokay, and Miss Lamort. I left the constable in charge downstairs and went up with Mr Harrison to rouse these three persons. The girl Burrage was fast asleep; we had to enter her room and wake her, and it took us quite a time. The young woman Bokay was already awake—she said the disturbance in the house had roused her. She was beginning to dress when we got there and seemed very scared. Those two rooms were in the top or attic story of the house, as you will see from the plan. It’s up there that all the servants sleep. We then came downstairs, and Mr Harrison took me to Miss Lamort’s room. There was a light shining under the door. The door was locked. Mr Harrison and I both took turns at knocking but could not get any reply for quite a while. At last we heard Miss Lamort’s voice asking, ‘Who’s there? Who’s there?’ Mr Harrison answered. He explained that there had been an accident and that everybody was wanted. We heard Miss Lamort getting out of bed. She came to the door at once and opened it. When she saw my uniform she seemed to stagger. She nearly fell, only Mr Harrison caught her in time. She said: ‘What’s happened? What’s happened?’ Mr Harrison told her that there had been an accident and that Mr Brunton was dead and that naturally the police had to make a few inquiries. She then said: ‘I must get some clothes on. I’ll come down.’ I waited. In a very short time she came to the door again, dressed, and I asked her to accompany me downstairs.

In the hall she rushed to Mrs Brunton and caught hold of her and seemed to break down properly. Mrs Brunton and Mrs Bayford tried to soothe her. I gave them permission to take her into the library, which opens just off the hall, so that she could lie down. I then entered the dining-room and began to call in the persons one by one. When I’d questioned Mr Harrison, Mrs Brunton and Mrs Bayford, Mr Adrian Brunton and Mr Hargreaves, I wanted to question Miss Lamort. I went into the library and found her. She was lying on the sofa. She was very pale and didn’t seem to appreciate what was going on.