Полная версия

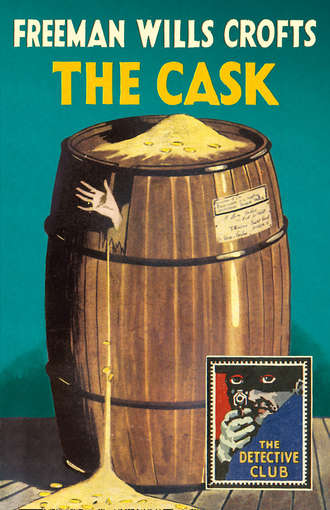

The Cask

Broughton emptied the cap on to the top of the cask. Three more sovereigns were found hidden in it, and these he pocketed with the others. Then he turned to re-examine the cask.

It was rather larger than the wine barrels, being some three feet six high by nearly two feet six in diameter. As already mentioned, it was of unusually strong construction, the sides, as shown by the broken stave, being quite two inches thick. Owing possibly to the difficulty of bending such heavy stuff, it was more cylindrical than barrel shaped, the result being that the ends were unusually large, and this no doubt partly accounted for Harkness’s difficulty in upending it. In place of the usual thin metal bands, heavy iron rings clamped it together.

On one side was a card label, tacked round the edges and addressed in a foreign handwriting: ‘M. Léon Felix, 141 West Jubb Street, Tottenham Court Road, London, W., via Rouen and long sea,’ with the words ‘Statuary only’ printed with a rubber stamp. The label bore also the sender’s name : ‘Dupierre et Cie., Fabricants de la Sculpture Monumentale, Rue Provence, Rue de la Convention, Grenelle, Paris.’ Stencilled in black letters on the woodwork was ‘Return to’ in French, English, and German, and the name of the same firm. Broughton examined the label with care, in the half-unconscious hope of discovering something from the handwriting. In this he was disappointed, but, as he held the hand-lamp close, he saw something else which interested him.

The label was divided into two parts, an ornamental border containing the sender’s advertisement and a central portion for the address. These two were separated by a thick black line. What had caught Broughton’s eye was an unevenness along this line, and closer examination showed that the central portion had been cut out, and a piece of paper pasted on the back of the card to cover the hole. Felix’s address was therefore written on this paper, and not on the original label. The alteration had been neatly done, and was almost unnoticeable. Broughton was puzzled at first, then it occurred to him that the firm must have run out of labels and made an old one do duty a second time.

‘A cask containing money and a human hand—probably a body,’ he mused. ‘It’s a queer business and something has got to be done about it.’ He stood looking at the cask while he thought out his course of action.

That a serious crime had been committed he felt sure, and that it was his duty to report his discovery immediately he was no less certain. But there was the question of the consignment of wines. He had been sent specially to the docks to check it, and he wondered if he would be right to leave the work undone. He thought so. The matter was serious enough to justify him. And it was not as if the wine would not be checked. The ordinary tallyman was there, and Broughton knew him to be careful and accurate. Besides, he could probably get a clerk from the dock office to help. His mind was made up. He would go straight to Fenchurch Street and report to Mr Avery, the managing director.

‘Harkness,’ he said, ‘I’m going up to the head office to report this. You’d better close up that hole as best you can and then stay here and watch the cask. Don’t let it out of your sight on any pretext until you get instructions from Mr Avery.’

‘Right, Mr Broughton,’ replied the foreman, ‘I think you’re doing the proper thing.’

They replaced as much of the sawdust as they could, and Harkness fitted the broken piece of stave into the space and drove it home, nailing it fast.

‘Well, I’m off,’ said Broughton, but as he turned to go a gentleman stepped down into the hold and spoke to him. He was a man of medium height, foreign looking, with a dark complexion and a black pointed beard, and dressed in a well-cut suit of blue clothes, with white spats and a Homburg hat. He bowed and smiled.

‘Pardon me, but you are, I presume, an I. and C. official?’ he asked, speaking perfect English, but with a foreign accent.

‘I am a clerk in the head office, sir,’ replied Broughton.

‘Ah, quite so. Perhaps then you can oblige me with some information? I am expecting from Paris by this boat a cask containing a group of statuary from Messrs Dupierre of that city. Can you tell me if it has arrived? This is my name.’ He handed Broughton a card on which was printed: ‘M. Léon Felix, 141 West Jubb Street, Tottenham Court Road, W.’

Though the clerk saw at a glance the name was the same as that on the label on the cask, he pretended to read it with care while considering his reply. This man clearly was the consignee, and if he were told the cask was there he would doubtless claim immediate possession. Broughton could think of no excuse for refusing him, but he was determined all the same not to let it go. He had just decided to reply that it had not yet come to light, but that they would keep a look out for it, when another point struck him.

The damaged cask had been moved to the side of the hold next the dock, and it occurred to the clerk that any one standing on the wharf beside the hatch could see it. For all he knew to the contrary, this man Felix might have watched their whole proceedings, including the making of the hole in the cask and the taking out of the sovereigns. If he had recognised his property, as was possible, a couple of steps from where he was standing would enable him to put his finger on the label and so convict Broughton of a falsehood. The clerk decided that in this case honesty would be the best policy.

‘Yes, sir,’ he answered, ‘your cask has arrived. By a curious coincidence it is this one beside us. We had just separated it out from the wine-barrels owing to its being differently consigned.’

Mr Felix looked at the young man suspiciously, but he only said: ‘Thank you. I am a collector of objets d’art, and am anxious to see the statue. I have a cart here and I presume I can get it away at once?’

This was what Broughton had expected, but he thought he saw his way.

‘Well, sir,’ he responded civilly, ‘that is outside my job and I fear I cannot help you. But I am sure you can get it now if you will come over to the office on the quay and go through the usual formalities. I am going there now and will be pleased to show you the way.’

‘Oh, thank you. Certainly,’ agreed the stranger.

As they walked off, a doubt arose in Broughton’s mind that Harkness might misunderstand his replies to Felix, and if the latter returned with a plausible story might let the cask go. He therefore called out:

‘You understand then, Harkness, you are to do nothing till you hear from Mr Avery,’ to which the foreman replied by a wave of the hand.

The problem the young clerk had to solve was three-fold. First, he had to go to Fenchurch Street to report the matter to his managing director. Next, he must ensure that the cask was kept in the Company’s possession until that gentleman had decided his course of action, and lastly, he wished to accomplish both of these things without raising the suspicions either of Felix or the clerks in the quay office. It was not an easy matter, and at first Broughton was somewhat at a loss. But as they entered the office a plan occurred to him which he at once decided on. He turned to his companion.

‘If you will wait here a moment, sir,’ he said, ‘I’ll find the clerk who deals with your business and send him to you.’

‘I thank you.’

He passed through the door in the screen dividing the outer and inner offices and, crossing to the manager’s room, spoke in a low tone to that official.

‘Mr Huston, there’s a man outside named Felix for whom a cask has come from Paris on the Bullfinch and he wants possession now. The cask is there, but Mr Avery suspects there is something not quite right about it, and he sent me to tell you to please delay delivery until you hear further from him. He said to make any excuse, but under no circumstances to give the thing up. He will ring you up in an hour or so when he has made some further inquiries.’

Mr Huston looked queerly at the young man, but he only said, ‘That will be all right,’ and the latter took him out and introduced him to Mr Felix.

Broughton delayed a few moments in the inner office to arrange with one of the clerks to take up his work on the Bullfinch during his absence. As he passed out by the counter at which the manager and Mr Felix were talking, he heard the latter say in an angry tone:

‘Very well, I will go now and see your Mr Avery, and I feel sure he will make it up to me for this obstruction and annoyance.’

‘It’s up to me to be there first,’ thought Broughton, as he hurried out of the dock gates in search of a taxi. None was in sight and he stopped and considered the situation. If Felix had a car waiting he would get to Fenchurch Street while he, Broughton, was looking round. Something else must be done.

Stepping into the Little Tower Hill Post Office, he rang up the head office, getting through to Mr Avery’s private room. In a few words he explained that he had accidentally come on evidence which pointed to the commission of a serious crime, that a man named Felix appeared to know something about it, and that this man was about to call on Mr Avery, continuing:

‘Now, sir, if you’ll let me make a suggestion, it is that you don’t see this Mr Felix immediately he calls, but that you let me into your private office by the landing door, so that I don’t need to pass through the outer office. Then you can hear my story in detail and decide what to do.’

‘It all sounds rather vague and mysterious,’ replied the distant voice, ‘can you not tell me what you found?’

‘Not from here, sir, if you please. If you’ll trust me this time, I think you’ll be satisfied that I am right when you hear my story.’

‘All right. Come along.’

Broughton left the post office and, now when it no longer mattered, found an empty taxi. Jumping in, he drove to Fenchurch Street and, passing up the staircase, knocked at his chief’s private door.

‘Well, Broughton,’ said Mr Avery, ‘sit down there.’ Going to the door leading to the outer office he spoke to Wilcox.

‘I’ve just had a telephone call and I want to send some other messages. I’ll be engaged for half an hour.’ Then he closed the door and slipped the bolt.

‘You see I have done as you asked and I shall now hear your story. I trust you haven’t put me to all this inconvenience without a good cause.’

‘I think not, sir, and I thank you for the way you have met me. What happened was this,’ and Broughton related in detail his visit to the docks, the mishap to the casks, the discovery of the sovereigns and the woman’s hand, the coming of Mr Felix and the interview in the quay office, ending up by placing the twenty-one sovereigns in a little pile on the chief’s desk.

When he ceased speaking there was silence for several minutes, while Mr Avery thought over what he had heard. The tale was a strange one, but both from his knowledge of Broughton’s character as well as from the young man’s manner he implicitly believed every word he had heard. He considered the firm’s position in the matter. In one way it did not concern them if a sealed casket, delivered to them for conveyance, contained marble, gold, or road metal, so long as the freight was paid. Their contract was to carry what was handed over to them from one point to another and give it up in the condition they received it. If anyone chose to send sovereigns under the guise of statuary, any objection that might be raised concerned the Customs Department, not them.

On the other hand, if evidence pointing to a serious crime came to the firm’s notice, it would be the duty of the firm to acquaint the police. The woman’s hand in the cask might or might not indicate a murder, but the suspicion was too strong to justify them in hiding the matter. He came to a decision.

‘Broughton,’ he said, ‘I think you have acted very wisely all through. We will go now to Scotland Yard, and you may repeat your tale to the authorities. After that I think we will be clear of it. Will you go out the way you came in, get a taxi, and wait for me in Fenchurch Street at the end of Mark Lane.’

Mr Avery locked the private door after the young man, put on his coat and hat, and went into the outer office.

‘I am going out for a couple of hours, Wilcox,’ he said.

The head clerk approached with a letter in his hand.

‘Very good, sir. A gentleman named Mr Felix called about 11.30 to see you. When I said you were engaged, he would not wait, but asked for a sheet of paper and an envelope to write you a note. This is it.’

The managing director took the note and turned back into his private office to read it. He was puzzled. He had said at 11.15 he would be engaged for half an hour. Therefore Mr Felix would only have had fifteen minutes to wait. As he opened the envelope he wondered why that gentleman could not have spared this moderate time, after coming all the way from the docks to see him. And then he was puzzled again, for the envelope was empty!

He stood in thought. Had something occurred to startle Mr Felix when writing his note, so that in his agitation he omitted to enclose it? Or had he simply made a mistake? Or was there some deep-laid plot? Well, he would see what Scotland Yard thought.

He put the envelope away in his pocket-book and, going down to the street, joined Broughton in the taxi. They rattled along the crowded thoroughfares while Mr Avery told the clerk about the envelope.

‘I say, sir,’ said the latter, ‘but that’s a strange business. When I saw him, Mr Felix was not at all agitated. He seemed to me a very cool, clear-headed man.’

It happened that about a year previously the shipping company had been the victim of a series of cleverly-planned robberies, and, in following up the matter, Mr Avery had become rather well acquainted with two or three of the Yard Inspectors. One of these in particular he had found a shrewd and capable officer, as well as a kindly and pleasant man to work with. On arrival at the Yard he therefore asked for this man, and was pleased to find he was not engaged.

‘Good-morning, Mr Avery,’ said the Inspector, as they entered his office, ‘what good wind blows you our way today?’

‘Good-morning, Inspector. This is Mr Broughton, one of my clerks, and he has got a rather singular story that I think will interest you to hear.’

Inspector Burnley shook hands, closed the door, and drew up a couple of chairs.

‘Sit down, gentlemen,’ he said. ‘I am always interested in a good story.’

‘Now, Broughton, repeat your adventures over again to Inspector Burnley.’

Broughton started off and, for the second time, told of his visit to the docks, the damage to the heavily-built cask, the finding of the sovereigns and the woman’s hand, and the interview with Mr Felix. The Inspector listened gravely and took a note or two, but did not speak till the clerk had finished, when he said:

‘Let me congratulate you, Mr Broughton, on your very clear statement.’

‘To which I might add a word,’ said Mr Avery, and he told of the visit of Mr Felix to the office and handed over the envelope he had left.

‘That envelope was written at 11.30,’ said the Inspector, ‘and it is now nearly 12.30. I am afraid this is a serious matter, Mr Avery. Can you come to the docks at once?’

‘Certainly.’

‘Well, don’t let us lose any time.’ He threw a London directory down before Broughton. ‘Just look up this Felix, will you, while I make some arrangements.’

Broughton looked for West Jubb Street, but there was no such near Tottenham Court Road.

‘I thought as much,’ said Inspector Burnley, who had been telephoning. ‘Let us proceed.’

As they reached the courtyard a taxi drew up, containing two plain clothes men as well as the driver. Burnley threw open the door, they all got in, and the vehicle slid quickly out into the street.

Burnley turned to Broughton. ‘Describe the man Felix as minutely as you can.’

‘He was a man of about middle height, rather slightly and elegantly built. He was foreign-looking, French, I should say, or even Spanish, with dark eyes and complexion, and black hair. He wore a short, pointed beard. He was dressed in blue clothes of good quality, with a dark green or brown Homburg hat, and black shoes with light spats. I did not observe his collar and tie specially, but he gave me the impression of being well dressed in such matters of detail. He wore a ring with some kind of stone on the little finger of his left hand.’

The two plain clothes men had listened attentively to the description, and they and the Inspector conversed in low tones for a few moments, when silence fell on the party.

They stopped opposite the Bullfinch’s berth and Broughton led the way down.

‘There she is,’ he pointed, ‘if we go to that gangway we can get down direct to the forehold.’

The two plain-clothes men had also alighted and the five walked in the direction indicated. They crossed the gangway and, approaching the hatchway, looked down into the hold.

‘There’s where it is,’ began Broughton, pointing down, and then suddenly stopped.

The others stepped forward and looked down. The hold was empty. Harkness and the cask were gone!

CHAPTER II

INSPECTOR BURNLEY ON THE TRACK

THE immediate suggestion was, of course, that Harkness had had the cask moved to some other place for safety, and this they set themselves to find out.

‘Get hold of the gang that were unloading this hold,’ said the Inspector.

Broughton darted off and brought up a stevedore’s foreman, from whom they learned that the forehold had been emptied some ten minutes earlier, the men having waited to complete it and then gone for dinner.

‘Where do they get their dinner? Can we get hold of them now?’ asked Mr Avery.

‘Some of them, sir, I think. Most of them go out into the city, but some use the night watchman’s room where there is a fire.’

‘Let’s go and see,’ said the Inspector, and headed by the foreman they walked some hundred yards along the quay to a small brick building set apart from the warehouses, inside and in front of which sat a number of men, some eating from steaming cans, others smoking short pipes.

‘Any o’ you boys on the Bullfinch’s lower forehold?’ asked the foreman, ‘if so, boss wants you ’alf a sec.’

Three of the men got up slowly and came forward.

‘We want to know, men,’ said the managing director, ‘if you can tell us anything about Harkness and a damaged cask. He was to wait with it till we got down.’

‘Well, he’s gone with it,’ said one of the men, ‘less’n ’alf an hour ago.’

‘Gone with it?’

‘Yes. Some toff in blue clothes an’ a black beard came up an’ give ’im a paper, an’ when ’e’d read it ’e calls out an’ sez, sez ’e, “’Elp me swing out this ’ere cask,” ’e says. We ’elps ’im, an’ ’e puts it on a ’orse dray—a four-wheeler. An’ then they all goes off, ’im an’ the cove in the blue togs walkin’ together after the dray.’

‘Any name on the dray?’ asked Mr Avery.

‘There was,’ replied the spokesman, ‘but I’m blessed if I knows what it was. ’Ere Bill, you was talking about that there name. Where was it?’

Another man spoke.

‘It was Tottenham Court Road, it was. But I didn’t know the street, and I thought that a strange thing, for I’ve lived off the Tottenham Court Road all my life.’

‘Was it East John Street?’ asked Inspector Burnley.

‘Ay, it was something like that. East or West. West, I think. An’ it was something like John. Not John, but something like it.’

‘What colour was the dray?’

‘Blue, very fresh and clean.’

‘Any one notice the colour of the horse?’

But this was beyond them. The horse was out of their line. Its colour had not been observed.

‘Well,’ said Mr Avery, as the Inspector signed that was all he wanted, ‘we are much obliged to you. Here’s something for you.’

Inspector Burnley beckoned to Broughton.

‘You might describe this man Harkness.’

‘He was a tall chap with a sandy moustache, very high cheekbones, and a big jaw. He was dressed in brown dungarees and a cloth cap.’

‘You hear that,’ said the Inspector, turning to the plain-clothes men. ‘They have half an hour’s start. Try to get on their track. Try north and east first, as it is unlikely they’d go west for fear of meeting us. Report to headquarters.’

The men hurried away.

‘Now, a telephone,’ continued the Inspector. ‘Perhaps you’d let me use your quay office one.’

They walked to the office, and Mr Avery arranged for him to get the private instrument in the manager’s room. He rejoined the others in a few minutes.

‘Well,’ he said, ‘that’s all we can do in the meantime. A description of the men and cart will be wired round to all the stations immediately, and every constable in London will be on the look-out for them before very much longer.’

‘Very good that,’ said the managing director.

The Inspector looked surprised.

‘Oh no,’ he said, ‘that’s the merest routine. But now I’m here I would like to make some other inquiries. Perhaps you would tell your people that I’m acting with your approval, as it might make them give their information more willingly.’

Mr Avery called over Huston, the manager.

‘Huston, this is Inspector Burnley of Scotland Yard. He is making some inquiries about that cask you already heard of. I’ll be glad if you see that he is given every facility.’ He turned to the Inspector. ‘I suppose there’s nothing further I can do to help you? I should be glad to get back to the City again, if possible.’

‘Thank you, Mr Avery, there’s nothing more. I’ll cruise round here a bit. I’ll let you know how things develop.’

‘Right. Good-bye then, in the meantime.’

The Inspector, left to his own devices, called Broughton and, going on board the Bullfinch, had the clerk’s story repeated in great detail, the actual place where each incident happened being pointed out. He made a search for any object that might have been dropped, but without success, visited the wharf and other points from which the work at the cask might have been overlooked, and generally made himself thoroughly familiar with the circumstances. By the time this was done the other men who had been unloading the forehold had returned from dinner, and he interviewed them, questioning each individually. No additional information was received.

The Inspector then returned to the quay office.

‘I want you,’ he asked Mr Huston, ‘to be so good as to show me all the papers you have referring to that cask, waybills, forward notes, everything.’

Mr Huston disappeared, returning in a few seconds with some papers which he handed to Burnley. The latter examined them and then said:

‘These seem to show that the cask was handed over to the French State Railway at their Rue Cardinet Goods Station, near the Gare St Lazare, in Paris, by MM. Dupierre et Cie., carriage being paid forward. They ran it by rail to Rouen, where it was loaded on to your Bullfinch.’

‘That is so.’

‘I suppose you cannot say whether the Paris collection was made by a railway vehicle?’

‘No, but I should think not, as otherwise the cartage charges would probably show.’

‘I think I am right in saying that these papers are complete and correct in every detail?’

‘Oh yes, they are perfectly in order.’

‘How do you account for the cask being passed through by the Customs officials without examination?’

‘There was nothing suspicious about it. It bore the label of a well-known and reputable firm, and was invoiced as well as stencilled, “Statuary only.” It was a receptacle obviously suitable for transporting such goods, and its weight was also in accordance. Unless in the event of some suspicious circumstance, cases of this kind are seldom opened.’

‘Thank you, Mr Huston, that is all I want at present. Now, can I see the captain of the Bullfinch?’

‘Certainly. Come over and I’ll introduce you.’