Полная версия

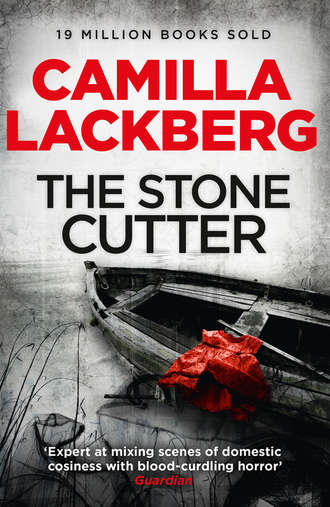

The Stonecutter

The binder he’d received from Fredrik felt heavy lying on his lap. It contained everything he needed to know. The whole fantasy world he himself was unable to create was gathered there inside the binder’s stiff covers and would soon be converted into ones and zeros. That was something he had mastered. While emotions, imagination, dreams and fairy tales had, by a caprice of nature, never found space in his brain, he was a wizard at the logical, the elegantly predictable in ones and zeros, the tiny electrical impulses in the computer that were converted into something legible on the screen.

Sometimes he wondered how it would feel to do what Fredrik was able to do. Plucking other worlds out of his brain, summoning up other people’s feelings and entering into their lives. Most often these speculations led Morgan to shrug his shoulders and dismiss them as unimportant. But during the periods of deep depression that sometimes struck him, he occasionally felt the full weight of his handicap and despaired that he had been made so different from everyone else.

At the same time it was a consolation to know that he was not alone. He often visited the websites of people who were like him, and he had exchanged emails with some of them. On one occasion he had even gone to meet one of them in Göteborg, but he wouldn’t be doing that again. The fact that they were so essentially different from other people made it hard for them to relate even to each other, and the meeting had been a failure from beginning to end.

But it had still been great to find out that there were others. That knowledge was enough. He actually felt no longing for the sense of community that seemed to be so important for ordinary people. He did best when he was all alone in the little cabin with only his computers to keep him company. Sometimes he tolerated his parents’ company, but they were the only ones. It was safe to spend time with them. He’d had many years to learn to read them, to interpret all the complex non-verbal communications in the form of facial expressions and body language and thousands of other tiny signals that his brain simply didn’t seem designed to handle. They had also learned to adapt themselves to him, to speak in a way that he could understand, at least adequately.

The screen before him was blank and waiting. This was the moment he liked best. Ordinary people might say that they ‘loved’ such a moment, but he wasn’t really sure what ‘loving’ involved. But maybe it was what he felt right now. That inner feeling of satisfaction, of belonging, of being normal.

Morgan began to type, making his fingers race over the keyboard. Once in a while he glanced down at the binder on his lap, but most often his gaze was fixed on the screen. He never ceased to be amazed that the problems he had coordinating the movements of his body and his fingers miraculously disappeared whenever he was working. Suddenly he was just as dextrous as he always should have been. They called it ‘deficient motor skills’, the problems he had with getting his fingers to move as they should when he had to tie his shoes or button his shirt. He knew that was part of the diagnosis. He understood precisely what made him different from the others, but he couldn’t do anything to change the situation. For that matter, he thought it was wrong to call the others ‘normal’ while people like him were dubbed ‘abnormal’. Actually it was only societal preconceptions that landed him in the wrong group. He was simply different. His thought processes simply moved in other directions. They weren’t necessarily worse, just not the same.

He paused to take a swig of Coca Cola straight out of the bottle, then his fingers moved rapidly over the keys again.

Morgan was content.

STRÖMSTAD 1923

Anders lay on the bed with his hands clasped behind his head, staring up at the ceiling. It was already late, and as always he felt the weight of a long day’s work in his limbs. But this evening he couldn’t seem to relax. So many thoughts were buzzing round in his head that it was like trying to sleep in the midst of a swarm of flies.

The meeting about the memorial stone had gone well, and that was one of the reasons for his ruminations. He knew that the job would be a challenge, and he ran through the different approaches, trying to decide on the best way to proceed. He already knew where he wanted to cut the big stone out of the mountain. In the south-west corner of the quarry there was a sizeable cliff that was as yet untouched. That was where he thought he could cut out a large, fine piece of granite. With a little luck the stone would be free of any defects or weaknesses that might cause it to crack.

The other reason for his musing was the girl with the dark hair and blue eyes. He knew that these were forbidden thoughts. Girls like that were not for someone like him; he shouldn’t even give them a thought. But he couldn’t help it. When he held her little hand in his he’d had to force himself to release it at once. With each second that her skin touched his, he felt it more difficult to let go, and he had never been fond of playing with fire. The whole meeting had been a trial. The hands on the clock on the wall had crept along, and the whole time he’d had to restrain himself from turning round and looking at her as she sat so quietly in the corner.

He’d never seen anyone so beautiful. None of the girls, or women for that matter, who had been a fleeting part of his life could even be mentioned in the same breath. She belonged to a whole other world. He sighed and turned on his side, attempting once again to get to sleep. The new day would begin at five o’clock, just like every other day, and took no account of whether he had lain awake all night mulling over his thoughts or had slept soundly.

There was a sharp noise. It sounded like a pebble hitting the windowpane, but the sound came and went so quickly that he wondered whether he’d just imagined it. In any case it was quiet now, so he closed his eyes again. But then the sound was back. There was no doubt about it. Someone was throwing pebbles at his window. Anders sat bolt upright. It must be one of the friends he sometimes joined for a beer. He thought indignantly that if his widowed landlady woke up, someone would have to answer for it. His lodging arrangement had functioned well for the past three years, and he didn’t need any trouble.

Cautiously he unlatched the window and opened it. He lived on the ground floor, but a big lilac bush partially blocked his view. He squinted to see who was standing in the faint moonlight.

And he couldn’t believe the testimony of his own eyes.

5

She hesitated for a long time. She even put on her jacket and then took it off again, twice. But finally Erica made up her mind. There could be nothing wrong with offering her support; then she could see whether Charlotte wanted to have a visitor or not. It felt impossible just to sit at home when she knew that her friend was mired in her own private hell.

As she walked she saw evidence of the storm from two days earlier still scattered along her route. Trees that had toppled, branches and debris lay strewn about, mixed with small piles of red and yellow leaves. But the wind also seemed to have blown away a dirty autumn layer that had settled over the town. Now the air smelled fresh, and it was as clear as a washed pane of glass.

Maja was shrieking at the top of her lungs in the pram, and Erica walked faster. For some reason the baby seemed to have decided that it was utterly meaningless to lie in the pram if she was awake, and she was again protesting loudly. Her screams made Erica’s heart beat faster, and tiny panicked beads of sweat appeared on her brow. A primitive instinct was telling her that she had to stop the pram at once and pick up Maja to save her from the wolves, but she steeled herself. It was such a short way to Charlotte’s mother’s house, and she would be there soon.

It was odd that a single event could alter so completely the way she looked at the world. Erica had always thought that the houses along the cove below the Sälvik campground stood like a peaceful string of pearls along the road, with a view over the sea and the islands. Now a gloomy mood seemed to have descended on the rooftops and especially onto the house of the Florin family. She hesitated once again, but now she was so close that it seemed foolish to turn round. They could just ask her to leave if they thought she was coming at an inopportune time. Friendships were tested in times of crisis, and she didn’t want to be one of those people who out of exaggerated caution and perhaps even cowardice avoided friends who were having a hard time.

Puffing, she pushed the pram up the hill. The Florins’ house was partway up the slope, and she paused for a second at their driveway to catch her breath. Maja’s yells had reached a decibel level that would have been classified as unlawful in a workplace, so she hurried to park the pram and picked her up in her arms.

For several long seconds she stood at the front door with her hand raised and her heart pounding. Finally she gave the wood a sharp rap. There was a doorbell, but sending that shrill sound into the house seemed somehow too intrusive. A long moment passed in silence, and Erica was just about to turn and go when she heard footsteps inside the house. It was Niclas who opened the door.

‘Hi,’ she said softly.

‘Hi,’ said Niclas, grief evident in his red-rimmed eyes, glistening with tears in his pale face. Erica thought that he looked like someone who had died but was still condemned to walk the earth.

‘Pardon me for bothering you, it’s not what I intended, I just thought …’ She sought for words but found none. A heavy silence settled between them. Niclas fixed his gaze on his feet, and for the second time since she knocked on the door Erica was about to turn on her heel and flee back home.

‘Would you like to come in?’ he asked.

‘Do you think it would be all right?’ Erica asked. ‘I mean, do you think it would be any …’ she searched for the right word, ‘help?’

‘She’s been given a sedative and isn’t really …’ He didn’t finish the sentence. ‘But she said several times that she should have rung you, so it would be good if you could reassure her on that point.’

The fact that Charlotte had worried about not ringing to cancel, after what had happened, told Erica something about how confused her friend must be. But when she followed Niclas into the living room she still couldn’t help uttering a startled cry. If Niclas looked like the walking dead, Charlotte looked like someone who’d been buried long ago. Nothing of the energetic, warm, lively Charlotte was left. It was as though an empty shell were lying on the sofa. Her dark hair, which usually formed a frame of curls around her face, now hung in lank wisps. The extra weight that her mother had always criticized had seemed becoming in Erica’s eyes, making Charlotte look like one of Zorn’s voluptuous Dalecarlian women. Yet as she lay huddled up under the blanket her complexion and body had taken on a doughy, unhealthy look.

She wasn’t asleep. Rather, her eyes stared lifelessly into empty space, and under the blanket she was shivering a little as if from the cold. Without taking off her jacket, Erica instinctively rushed over to Charlotte and knelt down on the floor by the sofa. She put Maja down on the floor beside her, and the baby seemed to sense the mood and lay perfectly still for a change.

‘Oh, Charlotte, I’m so sorry.’ Erica was crying and took Charlotte’s face in her hands, but there was no sign of life in her empty gaze.

‘Has she been like this the whole time?’ Erica asked, turning to Niclas. He was still standing in the middle of the room, swaying a little. Finally he nodded and wearily rubbed his hand over his eyes. ‘It’s the medication. But as soon as we stop the pills she starts screaming. She sounds like a wounded animal. I just can’t stand that sound.’

Erica turned back to Charlotte and stroked her hair tenderly. She didn’t seem to have bathed or changed her clothes in days, and her body gave off a faint odour of sweat and fear. Her mouth moved as if she wanted to say something, but at first it was impossible to make out anything from the mumbling. After trying for a moment, Charlotte said in a hoarse voice, ‘Couldn’t make it. Should have called.’

Erica shook her head vigorously and continued stroking her friend’s hair.

‘That doesn’t matter. Don’t worry about it.’

‘Sara, gone,’ said Charlotte, focussing her gaze on Erica for the first time. Her eyes seemed to burn right through her, they were so full of sorrow.

‘Yes, Charlotte. Sara is gone. But Albin is here, and Niclas. You’re going to have to help each other now.’ She could hear for herself that it sounded like she was simply mouthing platitudes, but maybe the simplicity of a cliché could reach Charlotte. Yet the only result was that Charlotte gave a wry smile and said in a dull, bitter voice: ‘Help each other.’ The smile looked more like a grimace, and there seemed to be some sort of underlying message in her bitter voice when she repeated those words. But maybe Erica was imagining things. Strong sedatives could produce strange effects.

A sound behind them made her turn round. Lilian was standing in the doorway, and she seemed to be choking with rage. She directed her flashing gaze at Niclas.

‘Didn’t we say that Charlotte wasn’t to have any visitors?’

The situation felt incredibly uncomfortable for Erica, but Niclas apparently took no notice of his mother-in-law’s tone of voice. Getting no answer from him, Lilian turned to look at Erica, who was still sitting on the floor.

‘Charlotte is feeling much too frail to have people running in and out. I should think everyone would know better!’ She made a gesture as if wanting to go over and shoo Erica away from her daughter like a fly, but for the first time Charlotte’s eyes showed some sign of life. She raised her head from the pillow and looked her mother straight in the eye. ‘I want Erica here.’

Her daughter’s protest merely increased Lilian’s rage, but with an obvious show of will she swallowed what she was about to say and stormed out to the kitchen. The commotion roused Maja from her temporary silence, and her shrill cries sliced through the room. Laboriously Charlotte sat up on the sofa. Niclas snapped out of his lethargy and took a quick step forward to help her. She brusquely waved him away and instead reached out to Erica.

‘Are you sure you’re all right sitting up? Shouldn’t you lie down and rest some more?’ Erica said anxiously, but Charlotte merely shook her head. Her speech was a bit slurred, but with obvious effort she managed to say ‘… lain here long enough.’ Then her eyes filled with tears and she whispered, ‘Not a dream?’

‘No, it was not a dream,’ said Erica. Then she didn’t know what else to say. She sat down on the sofa next to Charlotte, took Maja on her lap, and put one arm around her friend’s shoulders. Her T-shirt felt damp against her skin, and Erica wondered whether she dared suggest to Niclas that he help Charlotte take a shower and change her clothes.

‘Would you like another pill?’ asked Niclas, not daring even to look at his wife after being so roundly dismissed.

‘No more pills,’ Charlotte said, again shaking her head vigorously. ‘Have to keep a clear head.’

‘Would you like to take a shower?’ asked Erica. ‘I’m sure Niclas or your mother would be happy to help you.’

‘Couldn’t you help me?’ said Charlotte, whose voice was now sounding stronger with each sentence she uttered.

Erica hesitated for a moment, then she said, ‘Of course.’

With Maja on one arm she helped Charlotte up from the sofa and led her out of the living room.

‘Where’s the bathroom?’ Erica asked. Niclas pointed mutely to a door at the end of the hall.

The walk to that door felt endless. When they passed the kitchen, Lilian caught sight of them. She was just about to open her mouth and fire off a salvo when Niclas stepped in and silenced her with a look. Erica could hear an agitated muttering issuing from the kitchen, but she didn’t pay it much attention. The main thing was for Charlotte to feel better, and she was a firm believer in the restorative properties of a shower and a fresh change of clothes.

STRÖMSTAD 1923

It wasn’t the first time Agnes had sneaked out of the house. It was so easy. She just opened the window, climbed out on the roof and down the tree, whose thick crown was right next to the house. It was a piece of cake. But after careful consideration she’d decided not to wear a dress, which could make tree-climbing difficult. Instead she chose a pair of trousers with narrow legs that hugged her thighs.

She felt as if driven by an enormous wave, which she neither wanted to, nor could resist. It was both frightening and pleasant to feel such strong feelings for someone, and she realized that the fleeting infatuations she had previously taken seriously had been nothing but child’s play. What she felt now were the emotions of a grown woman, and they were more powerful than she could ever have imagined. During the many hours she’d spent pondering since that morning, she had occasionally been clear-sighted enough to understand that a longing for forbidden fruit was largely responsible for the heat in her breast. Nevertheless, the feeling was real, and she was not in the habit of denying herself anything. She was not about to start now, even though she had no precise plan. Only an awareness of what she wanted, and she wanted it now. Consequences were not something she ever took into consideration, and after all, things had always tended to work out for her, so why wouldn’t they now?

She did not even entertain the notion that Anders might not want her. To this day she had never met a man who was indifferent to her. Men were like apples on a tree, and she only needed to reach out her hand to pick them, though she was inclined to admit that this apple might present a slightly greater risk than most. She had kissed married men without her father’s knowledge, and in some instances had even gone farther than that, but they were all safer than the man she was about to meet. At least they belonged to the same class as she did. Even though it might have initially caused a scandal if her relations with any of them had come out, such affairs would have been regarded with a certain indulgence. But a man from the working class. A stonecutter. No one even dared think such a thought. It simply would never occur to them.

But she was tired of men from her own class. Spineless, pale, with limp handshakes and shrill voices. None of them was a man in the same way as the man she was about to meet. She shivered when she remembered the feeling of his callused hand against hers.

It hadn’t been easy to find out where he lived. Not without arousing suspicion. But a glance at the wage slips during an unguarded moment had provided his address, and then she had been able to work out which room was his by peering in the windows.

The first pebble produced no response, and she waited a moment, afraid of waking the old landlady. But no one moved inside the house. She paused to preen in the ethereal moonlight. She had chosen simple, dark clothing so as not to emphasize the difference in their social standing. For that reason she had also plaited her hair and wound it atop her head in one of the simple hairdos that were common among the working-class women. Pleased with the result, she picked up another pebble from the gravel walkway and tossed it against the window. Now she saw a shadow moving inside, and her heart skipped a beat. The euphoria of the chase pumped adrenaline into her body, and Agnes felt her cheeks flush. When he opened the window, puzzled, she sneaked behind the lilac bush that partly covered the window and took a deep breath. The hunt was on.

6

It was with a heaviness in both his heart and his step that Patrik left Mellberg’s office. What a damned old fool! That was the thought that immediately popped into his mind. He understood quite well that the superintendent had forced Ernst on him merely out of spite. If it wasn’t so bloody tragic it would almost be comical. How stupid.

Patrik went into Martin’s office, his body language signalling that things hadn’t gone the way they had imagined.

‘What did he say?’ asked Martin with dark foreboding in his voice.

‘Unfortunately he can’t spare you. You have to keep working on some car-theft mess. But he apparently has no problem getting along without Ernst.’

‘You’re kidding,’ Martin said in a low voice, since Patrik hadn’t closed the door behind him. ‘You and Lundgren are going to work together?’

Patrik nodded gloomily. ‘Looks that way. If we knew who the killer was we could send him a telegram and congratulate him. This investigation is going to be hopelessly sunk if I can’t keep him out of it as much as possible.’

‘Well, shit!’ said Martin, and Patrik could do nothing but agree. After a moment’s silence he slapped his hands on his thighs and stood up, trying to muster a little enthusiasm.

‘I suppose there’s nothing for it but to get to work.’

‘Where did you intend to start?’

‘Well, the first thing will be to inform the girl’s parents about the recent developments and cautiously try to ask a few questions.’

‘Are you taking Ernst along?’ Martin asked sceptically.

‘No, I think I’ll try to slip off by myself. Hopefully I can wait to inform him about his change of assignment until a little later.’

But when he came out in the corridor he realized that Mellberg had foiled his plans.

‘Hedström!’ Ernst’s voice, whiny and loud, grated on his ears.

For an instant Patrik considered running back into Martin’s office to hide, but he resisted this childish impulse. At least one person on this newly formed police team would have to behave like a grown-up.

‘Over here!’ He waved to Lundgren, who came steaming towards him. Tall and thin, and with a perpetually grumpy expression on his face, Ernst was not a pretty sight. What he was best at was sucking up and kicking down. He had neither the temperament nor the ability for regular police work. And after the incident of the past summer, Patrik considered his colleague downright dangerous because of his foolhardiness and desire to show off. And now he was forced to be partners with him. With a deep sigh he went to meet him.

‘I just talked to Mellberg. He said the little girl was murdered and that we’re going to lead the investigation together.’

Patrik looked nervous. He sincerely hoped that Mellberg hadn’t decided to subvert his authority behind his back.

‘What I think Mellberg said was that I’m going to lead the investigation and you’re going to work with me. Isn’t that right?’ said Patrik in a voice soft as velvet.

Lundgren looked down, but not fast enough for Patrik to miss a quick glimpse of loathing in his eyes. He had taken a gamble, but apparently it had worked. ‘Yes, I suppose that’s right,’ Ernst said crossly. ‘Well, where do we start – boss?’ He said the last word with deep contempt, and Patrik clenched his fists in frustration. After five minutes of this partnership he already wanted to throttle the fellow.

‘Come on, let’s go into my office.’ He led the way and sat down behind the desk. Ernst sat down in the visitor’s chair with his long legs stuck out in front of him.

Ten minutes later Ernst had been brought up to speed on all the information, and they grabbed their jackets to drive over to the house where Sara’s parents lived.