Полная версия

Waiting for Anya

Table of Contents

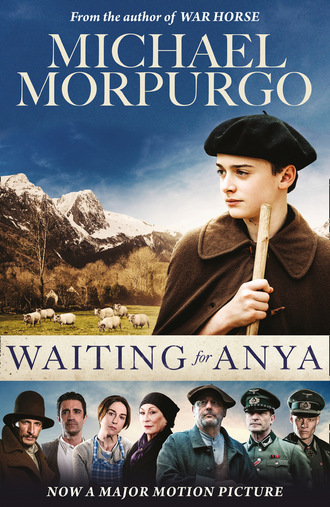

Cover

Title Page

Dedication and Copyright

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Back series promotional page

CHAPTER 1

JO SHOULD HAVE KNOWN BETTER. AFTER ALL PAPA had told him often enough: ‘Whittle a stick Jo, pick berries, eat, look for your eagle if you must,’ he’d said, ‘but do something. You sit doing nothing on a hillside in the morning sun with the tinkle of sheep bells all about you and you’re bound to drop off. You’ve got to keep your eyes busy, Jo. If your eyes are busy then they won’t let your brain go to sleep. And whatever you do, Jo, never lie down. Sit down but don’t lie down.’ Jo knew all that, but he’d been up since half past five that morning and milked a hundred sheep. He was tired, and anyway the sheep seemed settled enough grazing the pasture below him. Rouf lay beside him, his head on his paws, watching the sheep. Only his eyes moved.

Jo lay back on the rock and considered the lark rising above him and wondered why larks seem to perform when the sun shines. He could hear the church bells of Lescun in the distance but only faintly. Lescun, his village, his valley, where the people lived for their sheep and their cows. And they lived with them too. Half of each house was given over to the animals, a dairy on the ground floor, a hay loft above; and in front of every house was a walled yard that served as a permanent sheep fold.

For Jo the village was his whole world. He’d only been out of it a few times in all his twelve years, and one of those was to the railway station just two years before to see his father off to the war. They’d all gone, all the men who weren’t too young and who weren’t too old. It wouldn’t take long to hammer the Boche and they’d be back home again. But when the news had come it had all been bad, so bad you couldn’t believe it. There were rumours first of retreat and then of defeat, of French armies disintegrating, of English armies driven into the sea. Jo did not believe any of it at first, nor did anyone; but then one morning outside the Mairie he saw Grandpère crying openly in the street and he had to believe it. Then they heard that Jo’s father was a prisoner-of-war in Germany and so were all the others who had gone from the village; except Jean Marty, cousin Jean, who would never be coming back. Jo lay there and tried to picture Jean’s face; he could not. He could remember his dry cough though and the way he would spring down a mountain like a deer. Only Hubert could run faster than Jean. Hubert Sarthol was the giant of the village. He had the mind of a child and could only speak a few recognisable words. The rest of his talk was a miscellany of grunting and groaning and squeaking but somehow he managed to make himself more or less understood. Jo remembered how Hubert had cried when they told him he couldn’t join the army like the others. The bells of Lescun and the bells of the sheep blended in soporific harmony to lull him away into his dreams.

Rouf was the kind of dog that didn’t need to bark too often. He was a massive white mountain dog, old and stiff in his legs but still top dog in the village and he knew it. He was barking now though, a gruff roar of a bark that woke Jo instantly. He sat up. The sheep were gone. Rouf roared again from somewhere behind him, from in among the trees. The sheep bells were loud with alarm, their cries shrill and strident. Jo was on his feet and whistling for Rouf to bring them back. They scattered out of the wood and came running and leaping down towards him. Jo thought it was a lone sheep at first that had got itself caught up on the edge of the wood, but then it barked as it backed away and became Rouf – Rouf rampant, hackles up, snarling; and there was blood on his side. Jo ran towards him calling him back and it was then that he saw the bear and stopped dead. As the bear came out into the sunlight she stood up, her nose lifted in the air. Rouf stayed his ground, his body shaking with fury as he barked.

The nearest Jo had ever been to a bear before was to the bearskin that hung on the wall in the café. Stood up as she was she was as tall as a full-grown man, her coat a creamy brown, her snout black. Jo could not find his voice to shout with, he could not find his legs to run with. He stood mesmerised, quite unable to take his eyes off the bear. A terrified ewe blundered into him and knocked him over. Then he was on his feet, and without even a look over his shoulder he was running down towards the village. He careered down the slopes, his arms flailing to keep his balance. Several times he tumbled and rolled and picked himself up again, but as he gathered speed his legs would run away with him once more. All it needed was a rock or a tussock of grass to send him sprawling once again. Bruised and bloodied he reached the track to the village and ran, legs pumping, head back, and shouting whenever he could find the breath to do it.

By the time he reached the village – and never had it taken so long – he hadn’t the breath to say more than one word, but one word was all he needed. ‘Bear!’ he cried and pointed back to the mountains, but he had to repeat it several times before they seemed to understand or perhaps before they would believe him. Then his mother had him by the shoulders and was trying to make herself heard through the hubbub of the crowd about them.

‘Are you all right, Jo? Are you hurt?’ she said.

‘Rouf, Maman,’ he gasped. ‘There’s blood all over him.’

‘The sheep,’ Grandpère shouted. ‘What about the sheep?’

Jo shook his head. ‘I don’t know,’ he said. ‘I don’t know.’

Monsieur Sarthol, Hubert’s father and mayor of the village as long as Jo had been alive, was trying to organise loudly; but no one was paying him much attention. They had gone for their guns and for their dogs. Within minutes they were all gathered in the Square, some on horseback but most on foot. Those children that could be caught were shut indoors in the safekeeping of grandmothers, mothers or aunts; but many escaped their clutches and dived unseen into the narrow streets to join up with the hunting party as it left the village. A bear hunt was once in a lifetime and not to be missed. This was the stuff of legends and here was one in the making. Jo pleaded with Grandpère to be allowed to go but Grandpère could do nothing for him, Maman would have none of it. He was bleeding profusely from his nose and his knee, so despite all his objections he was bustled away into the house to have his wounds cleaned and bandaged. Christine, his small sister, gazed up at him with big eyes as Maman wiped away the blood.

‘Where’s the bear Jo?’ Christine asked. ‘Where’s the bear?’

Maman kept saying he was as pale as a ghost and should go and lie down. He appealed one last time to Grandpère, but Grandpère ruffled his hair proudly, took his hunting rifle from the corner of the room and went out with everyone else to hunt the bear.

‘Was it big, Jo?’ said Christine tugging at his arm. She was full of questions. You could never ignore Christine or her questions – she wouldn’t let you. ‘Was it as big as Hubert?’ And she held up her hands as high as she could.

‘Bigger,’ said Jo.

Bandaged like a wounded soldier he was taken up to his bedroom and tucked under the blankets. He stayed in bed only until Maman left the room, and then he sprang out of bed and ran to the window. He could see nothing but the narrow streets and the grey roofs of the village, and beyond the church-tower just a glimpse of the jagged mountain peaks still white in places with winter snow. The streets were empty of people, all except the priest, Father Lasalle, who was hurrying past, his hand on his hat to stop it blowing away.

All afternoon Jo watched as the clouds came down and began to swallow the valley. It was just after the church clock struck five that he heard a distant baying of dogs, and shortly after a volley of shots that echoed through the mountains and left a terrible silence hanging over the village.

He was down in the Square half an hour later with everyone else to watch the triumphant procession as it wound its way through the streets. Grandpère came first, Hubert gambolling alongside him.

‘We got her,’ Grandpère was shouting. ‘We got her. Give us a hand here Hubert, give us a hand.’ And they disappeared together into the café. They brought out two chairs each and set them down in front of the war memorial.

Limp in death, carried on two long poles by four men, the bear rocked into view, blood on her lolling tongue. She was laid out on the chairs, her legs hanging down on either side, her snout pressed up against the back of a chair. Jo was looking everywhere for Rouf but could not find him. He asked Grandpère if he had seen him but like everyone else Grandpère was too busy telling the story of the hunt or having his photograph taken. It was the grocer, Armand Jollet, who took pride of place in the photograph; it seemed he was the one who had actually shot the bear. He proclaimed this noisily, his round face red with pride and exhilaration. ‘Two hundred metres away I was, and I hit him right between the eyes.’

‘It’s a she,’ said Father Lasalle bending over the bear.

‘What’s the difference?’ said Armand Jollet. ‘He or she, that skin’s worth a fortune.’

In the celebrations that followed the photograph, the war was suddenly forgotten. Even Marie, Cousin Jean’s young widow, was laughing with them, swept along on a tide of communal joy and relief. Hubert clapped and cavorted about the place like a wild thing. He reared up like a bear and roared around the streets chasing screaming children and shouting, ‘Baar! Baar!’ Jo looked down at the bear and stroked her back. The fur was long and close and soft, the body still warm with life. Blood from the bear’s nose dropped on to his shoe and he felt suddenly sick. He turned to run away but Monsieur Sarthol had his arm around his shoulders and was calling for silence.

‘Here’s the lad himself,’ he said. ‘Without Jo Lalande there’d be no bear. This is the first bear we have shot in Lescun for over twenty-five years.’

‘Thirty,’ said Father Lasalle.

The Mayor ignored him and went on. ‘Lord knows how many of our sheep she’d have killed. We’ve a lot to thank him for.’ Jo saw Maman’s eyes smiling back at him in the front of the crowd but he could not smile back. The Mayor lifted his glass – most people seemed to have a glass in their hand by now. ‘So, here’s to Jo and here’s to the bear, and down with the Boche.’

‘Long live the bear,’ someone shouted and the laughter that followed echoed in Jo’s head. He could stand it no longer. He pulled away and ran, ignoring Maman’s call to come back.

Until the Mayor’s speech he had not thought about his part in it all. The she-bear was lying there dead, spread out on the chairs in the Square and he knew now it was all his doing. And perhaps Rouf was out there in the hills with his throat torn out, and none of it would have happened if he had not fallen asleep.

He ran all the way back along the track to the sheep pastures and up towards the trees. He stood there and called for Rouf again and again until his voice cracked, but only the crows answered him. He pushed the tears back out of his eyes and tried to calm himself, to remember the exact spot where he’d last seen Rouf. He called again, he whistled; but the clouds seemed to soak up the echoes. He looked up. There were no longer any mountains to be seen above the tree line, only a pall of thick mist. It was still now, not a whisper of wind. He could see where the sheep had been; there was wool caught on the bark of the trees, there were droppings here, footprints there. And then he saw the blood, Rouf’s blood perhaps, a brown smattering on the root of a tree.

He could not be sure what it was that he was hearing, not at first. He thought perhaps it was the mewing of an invisible buzzard flying through the clouds but then he heard the sound again and knew it for what it was, the whining of a dog – high-pitched and distant but now quite unmistakable. He called and he climbed, it was too steep to run. He ducked under low-slung branches, he clambered over fallen trees calling all the while: ‘I’m coming Rouf, I’m coming.’

The whining was punctuated now with a strange, intermittent growling, quite unlike anything he had heard before. He came upon Rouf sooner than he had expected. He spotted him through the trees sitting still as a rock, his head lowered as if he was pointing. He did not even turn round to look as Jo broke through into the clearing behind him. He seemed intent upon something in the mouth of a small cave. It was brown and it was small; and then it moved and became a bear cub. It was sitting in the shadows and waving one of its front paws at Rouf. Jo crouched down and put a hand on Rouf’s neck. Rouf looked up at him whining with excitement. He licked his lips and resumed his focus on the bear cub, his body taut. The bear cub rocked back against the side of the cave, legs apart, and growled. Yet it was hardly a growl, more a bleat of hunger, a cry for help, a call for mother. ‘They’ll kill him, Rouf,’ he whispered. ‘If they find out about him they’ll hunt him down and kill him, just like his mother.’ Still looking at the bear he stroked Rouf’s neck. It was matted and wet to the touch – like blood – but when he looked down at Rouf there wasn’t a mark on him.

Suddenly Rouf was on his feet, he swung round, hackles up, a rumbling growl in his throat. Jo turned. There was a man standing under the trees at the edge of the clearing. He wore a dirty black coat, a battered hat on his head. They looked at each other. Rouf stopped growling and his tail began to wag.

‘Only me again,’ said the man coming out of the trees towards them. Even with his hat he was a short man and as he came closer Jo saw that he had the gaunt, grey look of old men, yet his beard was rust red with not a fleck of white in it. There was a wine bottle in one hand and a stick in the other.

‘Milk,’ he said holding out the bottle. Rouf sniffed at it and the man laughed. ‘Not for you,’ he said and he patted Rouf on the head. ‘For the little fellow. Starving he is. Perhaps you’d hold my stick for me,’ he said. ‘We don’t want to frighten him do we?’ He gave his hat to Jo as well and took off his coat. ‘I saw the whole thing, you know. I saw you running off too. Your dog is he?’ Jo nodded. ‘Fights like a tiger doesn’t he? Bears like that can knock your head off you know. One swipe of the paw that’s all it takes. He was lucky. She tore his ear a bit, a lot of blood; but we soon cleaned you up didn’t we old son? Right as rain he is now.’ He bent down and poured some milk on to a rock. ‘Now, let’s see if we can get this little fellow to take a drink.’ He backed away a few paces and knelt down. ‘He’ll smell it soon, you’ll see. Give him time and he won’t be able to resist it.’ He sat back on his heels.

The cub ventured out of the shadows of the cave, lifting his nose and sniffing the air as he came. ‘Come on, come on little fellow,’ said the man, ‘we won’t hurt you.’ And he reached out very slowly and poured out some more milk but closer to the bear cub this time. ‘She could’ve got away you know.’

‘Who?’ said Jo.

‘The bear, the mother bear. I’ve been thinking about it. She was leading them away from her cub. Deliberate it was, I’m sure of it. And what’s more she led them a fair old dance I can tell you. Did you see the hunt?’ Jo shook his head. ‘Right away down the valley she took them, I saw it all – well most of it anyway. Course I couldn’t know why she was doing that, not at the time; and then I was on my way back home through the woods and there was this little fellow, and your dog just sitting here watching him. Covered in blood he was. Once I’d cleaned him up I went back home for some milk – the only thing I could think of. There you are, he’s coming for it now.’ The cub came forward tentatively, touched the milk with his paw, smelt it, licked it to taste and then began to lap noisily. Suddenly the man’s free arm shot out and scooped the cub on to his lap. There was a flurry of paws and a furious scratching and yowling until all the flailing arms and legs were trapped. His whole head was white with milk by now but the end of the bottle was in his mouth and he was sucking in deeply. The man looked up at Jo and smiled. He had milk all over his beard and was licking his lips. ‘Got him,’ he said and he chuckled until he laughed. The cub still clung to the bottle when it was empty and would not let go.

‘He’ll die out here on his own won’t he?’ said Jo.

‘No he won’t, not if we don’t let him,’ said the man and he tickled the cub under his chin. ‘Someone’s going to have to look after him.’

‘I can’t,’ said Jo. ‘They’d kill him. If I took him home they’d kill him, I know they would.’ He touched the pad of the cub’s paw, it was harder than he’d expected. The man thought for a while nodding slowly.

‘Well then, I’ll have to do it, won’t I?’ he said. ‘Won’t be long, only a month or two at the most I should think and then he’ll be able to cope on his own. I’ve got nothing much else to do with myself, not at the moment.’ For just a moment as he caught his eye Jo thought he recognised the man from somewhere before but he could not think where. Yet he was sure he knew everyone who lived in the valley – not by name necessarily, but by place or by face. ‘You don’t know who I am do you?’ said the man. It was as if he could read Jo’s thoughts. Jo shook his head. ‘Well that makes us even doesn’t it, because I don’t know you either. Maybe it’s better it stays that way. You’ve got to promise me never to say a word, you understand?’ There was a new urgency in his voice. ‘There was no cub, you never met me, you never even saw me. None of this ever happened.’ He reached out and gripped Jo’s arm tightly. ‘You have to promise me. Not a word to anyone – not your father, not your mother, not your best friend, no-one, not ever.’

‘All right,’ said Jo who was becoming alarmed. He felt the grip on his arm relax.

‘Good boy, good boy,’ he said and patted Jo’s arm.

The man looked up. The mist was filtering down through the treetops above them. ‘I’d better get back,’ he said. ‘I don’t want to get caught out in this, I’ll never find my way home.’

Once he was on his feet Jo gave him his hat and his stick. ‘Now you hang on to that dog of yours,’ he said. ‘I don’t want him following me home. Where one goes others can follow, if you understand my meaning.’ Jo wasn’t sure he did. The cub clambered up his shoulder and put an arm around his neck. ‘Seems to like me, doesn’t he?’ said the man. He turned to go and then stopped. ‘And don’t you go blaming yourself for what happened this afternoon. You had your job to do, and that old mother bear she had hers to do and that’s all there is to it. Besides,’ and he smiled broadly as the cub snuffled in his ear, ‘besides, if none of it had happened, we’d never have met would we?’

‘We haven’t met,’ said Jo catching Rouf by the scruff of his neck as he made to follow them. The man laughed.

‘Nor we have,’ he said. ‘Nor we have. And if we haven’t met we can’t say goodbye can we?’ And he turned, waved his stick above his head and walked away into the trees, the cub’s chin resting on his shoulder. The eyes that looked back at Jo were two little moons of milk.

CHAPTER 2

JO STOOD IN THE CLEARING AND LISTENED UNTIL he could no longer hear the man’s footsteps. The whole day had been like a bad dream that had turned suddenly and intensely intriguing – a dream he wanted to cling to. He knew if he walked away now he might never see the man or the bear cub again. He had to find out who he was and where he was going. He knew he shouldn’t but he had to follow him all the same.

Rouf did not have to be asked to follow the scent. He simply walked away into the trees and Jo went after him. From time to time he stopped to listen, but all he heard was Rouf’s purposeful panting ahead of him and the soft whisper of the mist falling through the trees. After a while he began to wonder if Rouf’s nose was failing him because they were following no track through the forest. Jo found himself sometimes climbing steeply and then scrambling downwards again clutching at treetrunks to keep himself upright. They seemed to be going back on themselves, almost round in circles at one point; but Rouf seemed sure enough of himself, plodding on resolutely until they broke out of the trees. Jo found himself looking down on the slate roofs of a farmstead.

He recognised at once where they were although he had never been near the place nor seen it from quite this direction. It was Widow Horcada’s farm. She lived alone up in the hills and kept herself to herself. She seemed to like it that way. She must have had a husband once but Jo had never known him and no one ever spoke of him. So far as anyone could tell she lived off her pigs that wandered everywhere – much to everyone’s annoyance – off one cow and off her honey; you could find her beehives ranged all along the hillside above the village. There was a line of them below him now, just a few metres away, but no bees that Jo could see. Jo had no desire to go any closer, and it wasn’t because he was afraid of bees.

Widow Horcada was not much liked in the village – ‘sinister’ Maman always called her – although Grandpère always defended her stoutly. The children in the village called her ‘The Black Widow’, and not just on account of the long black shawl she always wore over her head. Like every child in the village Jo had been mauled more than once by her sharp tongue. She made no secret of the fact that she did not like children, boys in particular. She was a person to avoid. He would go no further. But before Jo could grab him, Rouf was making his way past the beehives and down towards the buildings. Jo followed, whispering as loud as he dared for Rouf to stop. But Rouf did not stop.

There was a cow grazing in the small paddock below the house, her bell sounded as she pulled at the grass and looked up. The walled farmyard was full of snuffling, snorting pigs and that was clearly too much for Rouf – he did not like pigs, not one bit. He sat down outside the wall and waited for Jo. A light was on in the house and there were dark figures moving about in the downstairs room. There were voices coming from inside, raised voices; but he was too far away to hear what they were saying. One thing was certain though; one of the voices belonged to the man he had been following.

Jo thought of jumping the wall and running low across the yard towards the window but the boar was wandering towards him with menace in his eyes; so Jo went around the back. There was only one window, and to reach it he would have to climb up a stack of wood that was piled high against the wall. He climbed carefully until he could pull himself up and peer over the windowsill.

There were two people in the room. The man was bent over the sink splashing water over his face and Widow Horcada sat in a chair by the stove knitting feverishly. She was shaking her head and muttering something that Jo couldn’t hear. The man was wiping his face with a towel and talking through it at the same time.

‘Don’t you go worrying yourself about the boy,’ he said. ‘He doesn’t know who I am, what I am or where I live. We’ll be all right.’ He dropped the towel over the back of a chair and sat down at the table feeling his beard. ‘Worst thing about a beard,’ he said, ‘it never dries properly.’ And at that moment Jo remembered where he’d seen the man before.

It was the last summer before Papa had gone off to the war and he’d been up in the high mountain pastures with Papa, the first time he’d been allowed to go. Three long months they had spent up there together in the hut, milking the sheep every morning, making the cheese, then milking the sheep again in the evening. It had been a summer of hard work and soaring happiness – a summer alone with Papa, a summer living close to the eagles. Most people walking in the mountains passed by with a ‘Good morning’, or perhaps a request to drink at the spring but only two had ever come into the hut. They had appeared early one morning, a man with a red beard, a little girl clutching his hand. She’d have been five or six years old maybe with red hair like his. They had stayed until noon watching the sheep being milked and the cheese being made. They sat side by side and silent on Papa’s bed and watched fascinated as the rennet was poured in, as they heated and stirred the milk in the cauldrons, as Papa gathered the curd in his hands and squeezed out the whey. Jo remembered their silence and the intense seriousness on the little girl’s face. They asked the way up to the Spanish border and went off. It was raining when they came back later that afternoon. They brought with them a bunch of flowers, pinks they were and wild pansies. Jo could see them now in her hand. ‘From Spain to you,’ said the little girl, ushered forward by her father; and the man with the beard told them how they had walked to the top of the mountain and looked into Spain and how their legs ached. Papa had given them towels to dry themselves off. ‘Never grow a beard young man,’ the man had told him as he wiped his face. ‘You can never get it dry.’ Jo remembered Papa thanking them rather awkwardly and saying that no one had ever given him flowers before. They were already leaving before they introduced themselves. ‘I’m Madame Horcada’s son-in-law,’ he said shaking Papa’s hand, ‘and this is my daughter, Anya.’