Полная версия

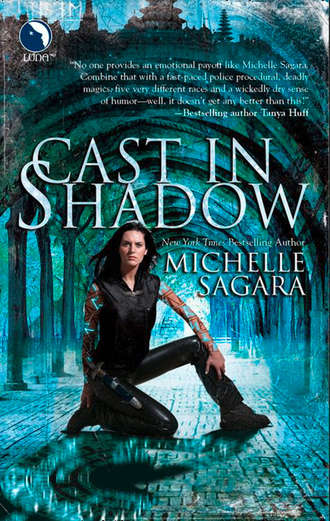

Cast In Shadow

And the fieflords ruled. They had their own laws, their own armies, their own lieges—everything but open warfare. Open war in the city would bring the army down upon them all. This was understood, and it was perhaps the only thing that kept the fieflords in check. But in Kaylin’s experience, it wasn’t near enough. People lived and died at their whim. Money ruled the fiefs; money and power.

But the people who lived in them, who lived in the old buildings, the crumbling tenements, the small, squalid houses, had neither. They made what living they could, and they dreamed of a time when they might cross the boundaries that divided the one city from the other, seeking freedom or safety in the streets beyond.

They might as well have lived in a different country.

“Kaylin?” Tinny, robbed of the threat and grandeur of a Dragon’s natural voice, she heard Tiamaris.

“Can you see it?”

Silence. A beat. “No,” he said quietly. “The gem is, as you claimed, keyed to you. It appears you are to be our conduit to the investigation.” He didn’t sound pleased, and she knew she was being petty when she felt a moment’s satisfaction.

But the satisfaction was very short-lived; the view dipped and veered, rolling in the sky. Clint had once taken her up in the air. She’d been with the Hawks for a handful of weeks, and she was thin with the hunger that dogged most children in the fiefs; he’d caught her under the arms, and she’d clung to him, determined to fly with him.

But she had found the distance from Clint to ground overwhelming. She couldn’t follow what she saw; couldn’t do anything but shut her eyes and shiver. Wind against her face, like it was now, was a reminder of what she wasn’t: Aerian, and meant for the skies.

But he’d held her tight, and his voice, in her ear, became an anchor. He teased a sense of security slowly out of her fear, her frozen stiffness, and she had at last opened those eyes and looked. He took her to his home, to the heights of the Aeries in the cliffs that bordered the southern face of the city.

His home was not the home she had fled.

Not the home that the crystal’s flight was returning her to.

The first fief passed beneath her shadow. She saw the tallest of the buildings it contained, and saw the gallows and the hanging cage that lay occupied beside it. Someone had angered the servants of the fieflord here, and they meant it to be known; the cage’s occupant—man? Woman? She couldn’t tell from this distance—was clearly still alive.

The voyager didn’t pause here; he merely observed.

From a distance, she was encouraged to do the same. But she had seen those cages from the ground; had watched a friend die in one, had discovered, on that day, what it meant to be truly powerless.

She struggled with the crystal, but she was overmastered here. The Hawks—her place in the Hawks—had given her the illusion of power. And the Hawklord was going to strip her of it before he let her leave. To remind her—as she had not reminded herself—that she was still powerless, still young.

This is the domain of the outcaste Barrani fieflord known as Nightshade, his voice said.We do not, of course, know his real name. It is hidden by spells far stronger than those we can comfortably use. Not even the Barrani castelords dare to challenge Nightshade in his own Dominion.

She closed her eyes. It didn’t help.

You know this fief.

She knew it. Severn knew it. They had lived, and almost died, in its streets. And Severn had done much, much worse there. The desire to kill him was paralyzing. It was wed to a bitter desire for justice—and justice was a fool’s dream in the fiefs.

There are deaths here which you must investigate. More information is forthcoming.

The crystal shifted in her hands, becoming almost too hot to hold. She held it anyway as her view suddenly banked and shifted.

She was on the ground. The smell of the streets, overpowering in its terrible familiarity, filled her senses. She staggered, stumbled, stood; she looked down to see that her tunic—an unfamiliar tunic, a man’s garb—was red with blood.

She felt no pain, but she knew that this memory was courtesy of the Tha’alani, and she hated it. It was different in all ways from the distant observation of the Hawklord; it was full of terror, of pain, of the inability to acknowledge or deny either.

She stumbled in the streets, and her arms ached; she was carrying something. No, he was, whoever he was. He stumbled along the busy streets; the sun was high. Some people watched him from a distance, open curiosity mixed with dread in their unfamiliar—blessedly so—faces. None approached. None offered him aid with the burden he bore. And when his strength at last gave out, when his knees bent, when his arms unlocked in a shudder that spoke of effort, of time, she saw why; saw it from his eyes.

A body rolled down his lap, bloody, devoid of life.

He screamed, then. A name, over and over, as if the name were a summons, as if it contained the power to command life to return.

But watching now as a Hawk, watching as someone trained to know death and its causes, Kaylin knew that it was futile.

The boy—ten years of age, maybe twelve—had been disemboweled. His arms hung slack by his sides, and she could see, from wrist to elbow, the black tattoos that had been painted there, indelible, in flesh.

She had seen them before. She knew that it wasn’t only his arms that bore those marks; his inner thighs would bear them, too.

She screamed.

And Severn screamed in quick succession as she inexplicably lost contact with the gem.

Her hands were blistered; her skin was broken along the lines of the rigid crystal. And so were Severn’s. He dropped the crystal instantly and it hit the table with a thunk, fastening itself to the wooden surface.

She thought it should roll.

It was a stupid thought.

“What are you doing?” She shouted at Severn, the words ground through clenched teeth, the pain in her hands making her stupid.

“Prying the gem away from you,” he snapped back, composure momentarily forgotten.

“Why?”

He shrugged. The shrug, which started at his shoulder, ended in a shudder. “You didn’t like what you were looking at,” he added quietly.

“And it matters?”

“Yes.”

“Why?”

He didn’t answer.

“That was brave,” Tiamaris said, speaking for the first time. “And very, very foolish. The Hawklord must have gone to some expense to create this crystal. It is … obviously unusual. Kaylin?”

She shook her head. Actually, she just shook. She wanted to touch the gem again, and she wanted to destroy it. Torn between the two—the one an imperative and the other an impossibility—she was frozen.

Tiamaris said quietly, “I owe you a debt.” The words were grave. His eyes had edged from red to gold, and the gold was liquid light.

“Debt?”

“I would have taken the gem. It would have been … unwise. It appears that the Hawklord trusts you, Kaylin. And it would appear,” he added, with just the hint of a dark smile, “that that trust does not extend to his newest recruits.”

But Severn refused to be drawn into the conversation; he was staring at Kaylin. His own hands had started to swell and blister.

“Did you see it?” she asked him, all enmity momentarily forgotten. He was Severn, she was Elianne, and the streets of the fiefs had become that most impossible of things: more terrifying than either had ever thought possible.

He shook his head. “No,” he said, devoid now of arrogance or ease. “But I know what you saw.”

“How?”

“I’ve only heard you scream that way once in your life,” he replied. He lifted a hand, as if to touch her, and she shied away instantly, her hand falling to her dagger hilt. To one of many.

He accepted her rejection as if it hadn’t happened. “I was there, back then,” he added quietly. “I saw it too. It’s happening again, isn’t it?”

She closed her eyes. After a moment, eyes still closed, she rolled up her sleeves, exposing the length of arm from wrist to elbow.

There, in black lines, in an elegant and menacing swirl, were tattoos that were almost twin to the ones upon the dead boy’s arms.

She was surprised when someone touched her wrist, and her eyes jerked open.

But Tiamaris held the wrist in a grip that could probably crush bone with little effort. Funny, how human his hands looked. How human they weren’t.

She tried to pull away. He didn’t appear to notice.

But his eyes flickered as she drew a dagger out of its sheath with her free hand. She’d moved slowly, and the daggers made no sound—but he was instantly aware of them.

“I wouldn’t, if I were you. Lord Grammayre is not known for his tolerance of fighting among his own.”

“Let go,” she whispered.

He didn’t appear to have heard her. “Do you know what these markings mean?” He asked. His inner eye membrane had risen, lending opacity to the sudden fire of his eyes.

“Death,” she whispered.

“Yes,” he replied. He studied them with care, and after a moment, she realized he was reading them. “They mean death. But that is not all they mean, Kaylin of the Hawks.”

“This isn’t—this isn’t Dragon.”

“No. It is far older than Dragon, as you so quaintly call our tongue.”

“Barrani?”

His lip curled in open disdain.

“I’ll take that as a no.” She hesitated. These patterns had been with her since she had gained the age of ten, a significant age in the fiefs. Not many children survived that long when they’d lost their parents.

“Where did you get these?”

“In Nightshade,” she whispered.

“Who put them upon you? Who marked you thus?”

It was Severn who answered. “No one.”

“Impossible.”

“I saw them,” Severn replied. “I saw them … grow. We all did. They started one morning in Winter.”

“On what day?”

“The shortest one.”

Tiamaris said nothing. She wanted him to continue to say nothing, but he opened his mouth anyway. “I saw the bodies,” he said at last. “And the tattoos of the dead did not just, as you say, ‘start.’ They were put there, and at some cost.”

“Not hers,” Severn said quietly.

Tiamaris frowned. “There is something here,” he said at last, “that even I cannot read.”

“Do you—do you know someone who can?”

“Only one,” Tiamaris replied, “and it would not be safe for you to ask him.”

“Why?”

“He would probably take both arms.”

Severn said, “He could try.” And his long dagger was suddenly in his hand.

Kaylin looked at it. Looked at Severn. Understood nothing at all. “How do you know how to read this?” she whispered.

“I am considered a scholar,” was his cautious reply. “I dabble in the antiquities.”

Which meant magery. She didn’t bother to ask.

“Let me go,” she said wearily, adding command to the words.

To her surprise, Tiamaris withdrew his grip. “You are interesting, Kaylin, as the Hawklord surmised. But I am surprised, now.”

“At what?”

“That the Hawklord let you live.”

Kaylin said nothing.

Again, for reasons that made no sense, Severn said, “Why?” His hands had once again fallen beneath the surface of the table.

“Your story … is strange. And you must understand that the deaths in the fiefs some years ago were also investigated.”

The deaths. Seven years ago. She shuddered.

For the first time since she’d met Tiamaris, his expression went bleak. The way distant, snow-covered cliffs were.

“You were there, back then,” she said softly.

“I was there.”

“And you weren’t a Hawk.”

“No.”

She lifted a shaking head. Looked down at her arms. “What does it mean?”

“I don’t know,” he replied, even now, eyes upon her face. “But in the end, the killings stopped. Does the Hawklord know of these?”

She nodded. She almost matched his bleakness. “He knows almost everything about me.”

“And he does not suspect that you were involved in the incidents.”

Her eyes rounded. She was too stunned to be angry; that might come later.

“You don’t understand, and clearly Grammayre did not see fit to inform you. As I will be working with you, I will. The first death must have occurred—and Lord Grammayre would be acquainted with the approximate time—on the day you say these appeared. On the same solstice.”

The silence was, as they say, deafening. And into the silence, the shadow of accusation crept.

“She had nothing to do with the deaths of the others,” Severn snapped. “They were all—”

Kaylin said, “Shut up, Severn.”

To her surprise, Severn did.

“I believe you” was the quiet reply. “Having met her, I believe you.” Tiamaris looked across the table at Kaylin; the table seemed to have grown very, very long. From that distance, he said, “You said that it had started again. Tell me what you think has started.”

She swallowed. Her mouth was very dry. “The deaths,” she whispered at last. “In Nightshade. I thought—when the first body appeared—I was so certain I would die next. Because of the marks. We all were.” “All?”

Her lips thinned. She didn’t answer the question. It wasn’t any of his damn business. A different life.

“What happened?”

She shook her head. Inhaled and rose, placing tender palms against the hard surface of scarred wood. “I didn’t die. I don’t know why,” she said at last. “But I do know where we’re going.”

“To Nightshade,” Severn said quietly.

“To Nightshade.” She started toward the door. Stopped.

She turned back to look at Severn, who had not risen to join her. “It’s not finished,” she told him softly.

He said nothing, but after a moment, added, “I know. Elianne—”

“I’m Kaylin,” she whispered. “Don’t forget it.”

“I won’t. Will you?”

She shook her head, and instead of murderous rage, she felt something different, something more dangerous. “I won’t forget what you did, in Nightshade.”

He said nothing at all.

“I need to get something to eat. Meet me in the front hall in an hour. No, two. Be ready.”

“For the fiefs?” He laughed bitterly.

Tiamaris, however, nodded.

She left the room, walking quietly and with a stately dignity that she seldom possessed. Only when she was certain she’d left them both behind did she stop to empty the negligible contents of her stomach.

Marcus was there, of course. As if he’d been waiting. He probably had. He placed velvet paw-pads upon her shoulder, and squeezed; she felt the full pads of his palms press into her tunic. Warmth, there.

“Kaylin.”

“I don’t want to go back,” she whispered, in a voice she hated. It was a thirteen-year-old’s voice. A child’s voice.

“Don’t tell me where you’re going. If I’m not mistaken, you’re bound.” He glanced at her blistered palm and his breath came out in a huff that sounded similar to a growl.

It was a comforting sound, or it was meant to be. If you knew a Leontine. She knew this one.

“But I can guess,” he added grimly. “Come. The quartermaster has given me what you requisitioned.”

“I didn’t—”

“The Hawklord understands where you’re going,” Marcus said quietly. “And he was prepared. He was not, I think, prepared for losing the half day. He’s docked your pay.”

“Bastard,” she whispered, but with no heat.

His hand ran over her rounded back. As if she were his, part of his pride. “I brought you this,” he said, when she at last straightened, her stomach still unsettled.

She knew what he held.

It looked like a bracer, but shorter, and it was golden in sheen. Three gems adorned it, and to the untrained eye, they were valuable: ruby, sapphire and diamond.

But Kaylin knew they were more than that. “I won’t lose control,” she started.

His eyes were as narrow as they ever got. “It wasn’t a request, Kaylin. I know where you’re going.”

“He told you?”

His nose wrinkled as he looked at the mess around her feet. And on it.

“Oh.”

“Put it on,” he told her, in a voice that brooked no refusal. A sergeant’s voice.

“Marcus—”

“Put it on, Kaylin. And if I were you, I wouldn’t remove it for a while.”

She took the bracer from his hands and stared at it. It had no apparent hinge, but that, too, was illusion. She touched the gems in a sequence that her fingers had never forgotten: blue, blue, red, blue, white, white. She felt magic’s familiar and painful prickle at the same time as she heard the unmistakable click of a cage door being opened.

“Did he tell you to make me do this?” she asked bitterly.

“No, Kaylin. I think he trusts you to know your own limits.”

“Do you?”

“Yes,” he said softly. But he waited while she slid the manacle over her left arm. “In as much as you can know them, I do.”

“What does that mean?”

“You know what it means.”

And she did. “I—I haven’t lost control since—”

“You weren’t in the fiefs, then.” He paused for just a moment, and then added, “Kaylin, your power—no one understands it. Not even the Hawklord. He’s kept it hidden. I’ve kept it hidden. He is the only one of the Lords of Law who knows what can happen when you lose it. And he’s the only one who should.”

She closed her eyes. “The Hawklord—”

“Trusts you. More than that, he shows some affection for you. I have come to understand his wisdom. Even if you can’t be on time to save your life or my reputation.” He turned away, then. “Leave the mess. I’ll have someone else clean it up.”

She still didn’t move.

And heard his growling sigh. He turned back. “What you did with Sesti, what you did with one of my own pride-wives, is not something that either the Hawklord or I could have predicted could be done.”

“Sesti was—”

“Kaylin. You wouldn’t have gone to Sesti if you thought she’d survive the birthing on her own. You would never have risked the exposure. You’ve been damn careful. You’ve had to be. But you saved her, you saved her son. You saved mine. I wouldn’t make you wear this if you were going someplace where I thought you’d have to—”

She lifted her hand. “It’s on, Marcus,” she said, weary now.

The last thing she wanted to think about was power.

Because she’d discovered over the years that it always, always had a price, and someone had to pay it.

CHAPTER

3

You’re an hour late,” Severn snapped.

“You had something better to do?” She ran a hand across her eyes and winced; it was her blistered hand.

“Than being stared at by a bunch of paper-pushing Hawks?” He spit to the side.

“We didn’t ask you to transfer,” she snapped back. Not that she was fond of being stared at, either—but she was used to it, by now. Besides, it meant that Marcus’s fur had settled enough that the rest of the office had decided it was safe to come back to work.

“In the event that it comes as a surprise,” Tiamaris said, in his deep, neutral tone, “Kaylin is not known for her punctuality. She is known, in fact, for her lack—even by those outside of the Hawklord’s command.”

Used to it or not, no one liked to be reminded that they were a public embarrassment. Kaylin flushed.

“Here,” Severn said, and tossed her a vest. It was made of heavy, molded leather, and it was—surprise, surprise—her size. It was the only armor she wore. “Your quartermaster moves. You’re sure you’re just a Hawk?”

“What else would I be?”

His expression shifted into an unpleasantly serious one. “A Shadow Hawk,” he said quietly.

“I don’t live in the shadows,” she murmured uneasily.

“Since when?”

When she offered no answer at all, he added, “Put the armor on, Kaylin.”

She grimaced.

Another habit that had come from the fiefs; you didn’t want anything weighing you down, because if you had to bolt, you were doing it at top speed, and usually with a bunch of armed thugs giving chase. Severn had changed; he wore leathers without comment. They suited him.

He also wore a long, glittering chain, thin links looped several times around his waist like a fashion statement. She doubted it was decorative.

But she had her own decorations.

Neither of them wore the surcoats that clearly marked the Hawks—or any of the city guards. No point, in the fiefs, unless you wanted to be target practice.

“You’ve got expensive taste,” he said, staring at the edge of the manacle that peered out from beneath her tunic. The gold was unmistakable. “I guess you get better pay than the Wolves do. We don’t even get a chance to loot the fallen.”

Tiamaris eyed them both with disdain.

“Where’s your armor?” she asked the Dragon. Anything to change the subject.

“I don’t require any.”

She raised a brow. She’d heard that a dozen times, usually from young would-be recruits. But then again, none of them had ever been a Dragon.

“We’re not covert,” she snapped.

“No one is, in the fiefs.” His shrug was elegant. It made boredom look powerful.

Severn had a long knife, a couple of obvious daggers.

She had the rest of her kit, her throwing knives, the ring that all Hawks wore. She twisted the last almost unconsciously.

“Why were you late this time?” Severn asked quietly.

She started to tell him to mind his own business, and managed to stop herself. She was about to go into the fief of Nightshade with him. She wanted to kill him. And she knew what the Hawks demanded. Balancing these, she said, “I went back for the rest of the information in the damn crystal.”

“Without us?”

She nodded grimly.

“How bad?”

“It’s bad,” she said quietly. Really, really bad. But she didn’t share easily. “There were two deaths. Two boys.”

His expression didn’t change. He’d schooled it about as well as she now schooled hers. “When?”

“Three days apart.”

Tiamaris’s brows rose. “Three days?”

She nodded quietly.

“Kaylin—I’m not sure how aware you were of what happened the last time … you were a child.”

“I was aware of it,” she whispered. “Because I was a child in the fiefs.”

“There were exactly thirteen deaths a year for almost three years. We could time them by moon phase,” Tiamaris added. “The Dark moon. At no time in the previous incident did the deaths occur at such short intervals.”

She nodded almost blankly.

“Where did the new deaths take place?” Severn’s voice was harsh.

“Nightshade,” she said bitterly, shaking herself. “The fieflord must have been in a good mood. We didn’t lose anyone while we were investigating the deaths.”

Severn whistled.

“Timing or no, it was the same,” she added hollowly. “As last time. The examiner’s reports were also in crystal.”

“And the Hawks’ mages?”

She nodded. “Their reports are there as well. Or rather, their précis on the findings. It’s all bullshit.”

“What kind of bullshit?”

“The unintelligible kind. You take magic exams in the Wolves?”

He shrugged. “Take them, or pass them?”

In spite of herself, she laughed. “Me, too.” And then she forced her lips down, thinning them. Remembering Severn’s last act.

He knew, too. He looked at her, his gaze steady. “Elia—Kaylin,” he corrected himself, “it wasn’t—”

But she lifted a hand. She didn’t want to hear it.

Severn took a step closer, and her hand fell to a dagger. He ignored it. Her hand tightened.

Rescue came from an unexpected quarter.

“If you’re both ready,” Tiamaris said, glancing at the very high windows in the change rooms, “we’re late.”

“For what?”

“There are only so many hours of daylight, and not even I want to be in the fiefs at night.”