Полная версия

The Sapphire Rose

DAVID EDDINGS

The Sapphire Rose

The Elenium

BOOK THREE

Copyright

HarperVoyager An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpervoyagerbooks.co.uk

This edition 1995

Previously published in paperback by Grafton 1992, reprinted once, and by HarperCollins Science Fiction & Fantasy 1993, reprinted twice

First published in Great Britain by Grafton 1991

Copyright © David Eddings 1991

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2015 Cover images © Shutterstock.com

The Author asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Source ISBN: 9780007127832

Ebook Edition © JUNE 2010 ISBN: 9780007375080

Version 2015-03-20

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

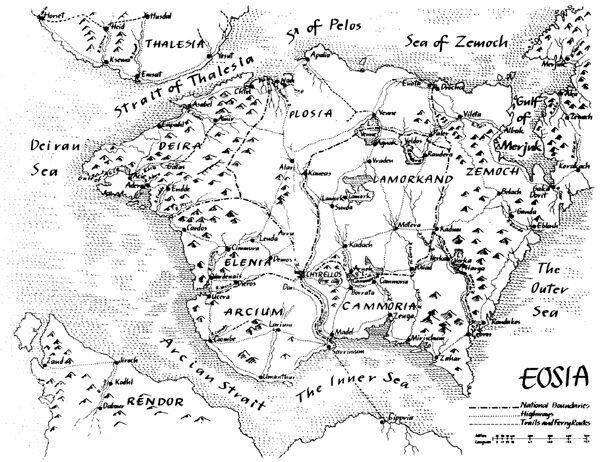

Map

Prologue

Part One: The Basilica

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Part Two: The Archprelate

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Part Three: Zemoch

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Epilogue

Author’s Note

About the Author

Also by the Author

About the Publisher

Map

Prologue

Otha and Azash – Excerpted from A Cursory History of Zemoch. Compiled by the History Department of the University of Borrata.

Following the invasion of the Elenic-speaking peoples from the steppes of central Daresia lying to the east, the Elenes gradually migrated westward to displace the thinly scattered Styrics who inhabited the Eosian continent. The tribes which settled in Zemoch were latecomers, and they were far less advanced than their cousins to the west. Their economy and social organization were simplistic, and their towns rude by comparison with the cities which were springing up in the emerging western kingdoms. The climate of Zemoch, moreover, was at best inhospitable, and life there existed at the subsistence level. The Church found little to attract her attention to so poor and unpleasant a region; and as a result, the rough chapels of Zemoch became largely unpastored and their simple congregations untended. Thus the Zemochs were obliged to take their religious impulses elsewhere. Since there were few Elene priests in the region to enforce the Church ban on consorting with the heathen Styrics, fraternization became common. As the simple Elene peasantry perceived that their Styric neighbours were able to reap significant benefits from the use of the arcane arts, it is perhaps only natural that apostasy became rampant. Whole Elenic villages in Zemoch were converted to Styric pantheism. Temples were openly erected in honour of this or that topical God, and the darker Styric cults flourished. Intermarriage between Elene and Styric became common, and by the end of the first millennium, Zemoch could no longer have been considered in any light to be a true Elenic nation. The centuries and the close contact with the Styrics had even so far corrupted the Elenic language in Zemoch that it was scarcely intelligible to western Elenes.

It was in the eleventh century that a youthful goatherd in the mountain village of Ganda in central Zemoch had a strange and ultimately earth-shaking experience. While searching in the hills for a straying goat, the lad, Otha by name, came across a hidden, vine-covered shrine which had been erected in antiquity by one of the numerous Styric cults. The shrine had been raised to a weathered idol which was at once grotesquely distorted and at the same time oddly compelling. As Otha rested from the rigours of his climb, he heard a hollow voice address him in the Styric tongue. ‘Who art thou, boy?’ the voice inquired.

‘My name is Otha,’ the lad replied haltingly, trying to remember his Styric.

‘And hast thou come to this place to pay obeisance to me, to fall down and worship me?’

‘No,’ Otha answered with uncharacteristic truthfulness. ‘What I’m really doing is trying to find one of my goats.’

There was a long pause. Then the hollow, chilling voice continued. ‘And what must I give thee to wring from thee thine obeisance and thy worship? None of thy kind hath attended my shrine for five thousand years, and I hunger for worship – and for souls.’

Otha was certain at this point that the voice was that of one of his fellow herders playing a prank on him, and he determined to turn the joke around. ‘Oh,’ he said in an offhand manner, ‘I’d like to be the king of the world, to live forever, to have a thousand ripe young girls willing to do whatever I wanted them to do, and a mountain of gold – and, oh yes, I want my goat back.’

‘And wilt thou give me thy soul in exchange for these things?’

Otha considered it. He had been scarcely aware of the fact that he had a soul, and so its loss would hardly inconvenience him. He reasoned, moreover, that if this were not, in fact, some juvenile goatherd prank, and if the offer were serious, failure to deliver even one of his impossible demands would invalidate the contract. ‘Oh, all right,’ he agreed with an indifferent shrug, ‘– but first I’d like to see my goat – just as an indication of good faith.’

‘Turn thee around then, Otha,’ the voice commanded, ‘and behold that which was lost.’

Otha turned, and sure enough, there stood the missing goat, idly chewing on a bush and looking curiously at him. Quickly he tethered her to the bush. At heart, Otha was a moderately vicious lad. He enjoyed inflicting pain on helpless creatures. He was given to cruel practical jokes, to petty theft, and, whenever it was safe, to a form of seduction of lonely shepherdesses that had only directness to commend it. He was avaricious and slovenly, and he had a grossly overestimated opinion of his own cleverness. His mind worked very fast as he tied his goat to the bush. If this obscure Styric divinity could deliver a lost goat upon demand, what else might He be capable of? Otha decided that this might very well be the opportunity of a lifetime. ‘All right,’ he said, feigning simple-mindedness, ‘one prayer – for now – in exchange for the goat. We can talk about souls and empires and wealth and immortality and women later. Show yourself. I’m not going to bow down to empty air. What’s your name, by the way? I’ll need to know that in order to frame a proper prayer.’

‘I am Azash, most powerful of the Elder Gods, and if thou wilt be my servant and lead others to worship me, I will grant thee far more than thou hast asked. I will exalt thee and give thee wealth beyond thine imagining. The fairest of maidens shall be thine. Thou shalt have life unending, and, moreover, power over the spirit world such as no man hath ever had. All I ask in return, Otha, is thy soul and the souls of those others thou wilt bring to me. My need and my loneliness are great, and my rewards unto thee shall be equally great. Look upon my face now, and tremble before me.’

There was a shimmering in the air surrounding the crude idol, and Otha saw the reality of Azash hovering about the roughly-carved image. He shrank in horror before the awful presence which had so suddenly appeared before him and fell to the ground, abasing himself before it. This was going much too far. At heart, Otha was a coward, however, and he was afraid that the most rational response to the materialized Azash – instant flight – might provoke the hideous God into doing nasty things to him, and Otha was extremely solicitous of his own skin.

‘Pray, Otha,’ the idol gloated. ‘Mine ears hunger for thine adoration.’

‘Oh, mighty – um – Azash, wasn’t it? God of Gods and Lord of the World, hear my prayer and receive my humble worship. I am as the dust before thee, and thou towerest above me like the mountain. I worship thee and praise thee and thank thee from the depths of my heart for the return of this miserable goat – which I will beat senseless for straying just as soon as I get her home.’ Trembling, Otha hoped that the prayer might satisfy Azash – or at least distract Him enough to provide him an opportunity for escape.

‘Thy prayer is adequate, Otha,’ the idol acknowledged, ‘– barely. In time thou wilt become more proficient in thine adoration. Go now thy way, and I will savour this rude prayer of thine. Return again on the morrow, and I will disclose my mind further unto thee.’

As he trudged home with his goat, Otha vowed never to return, but that night he tossed on his rude pallet in the filthy hut where he lived, and his mind was afire with visions of wealth and subservient young women upon whom he could vent his lust. ‘Let’s see where this goes,’ he muttered to himself as the dawn marked the end of the troubled night. ‘If I have to, I can always run away later.’

And that began the discipleship of a simple Zemoch goatherd to the Elder God, Azash, a God whose name Otha’s Styric neighbours would not even utter, so great was their fear of Him. In the centuries which followed, Otha realized how profound was his enslavement. Azash patiently led him through simple worship into the practice of perverted rites and beyond into the realms of spiritual abomination. The formerly ingenuous and only moderately disgusting goatherd became morose and sombre as the dreaded idol fed gluttonously upon his mind and soul. Though he lived a half-dozen lifetimes, his limbs withered, while his paunch and head grew bloated and hairless and pallid-white as a result of his abhorrence of the sun. He grew vastly wealthy, but took no pleasure in his wealth. He had eager concubines by the score, but he was indifferent to their charms. A thousand, thousand wraiths and imps and creatures of ultimate darkness responded to his slightest whim, but he could not even summon sufficient interest to command them. His only joy became the contemplation of pain and death as his minions cruelly wrenched and tore the lives of the weak and helpless from their quivering bodies for his entertainment. In that respect, Otha had not changed.

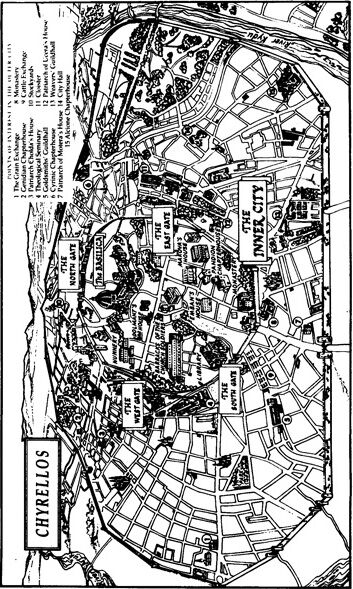

During the early years of the third millennium, after the slug-like Otha had passed his nine hundredth year, he commanded his infernal underlings to carry the rude shrine of Azash to the city of Zemoch in the northeast highlands. An enormous semblance of the hideous God was constructed to enclose the shrine, and a vast temple erected about it. Beside that temple and connected to it by a labyrinthine series of passageways stood his own palace, gilt with fine, hammered gold and inlaid with pearl and onyx and chalcedony and with its columns surmounted with intricately-carved capitals of ruby and emerald. There he indifferently proclaimed himself Emperor of all Zemoch, a proclamation seconded by the thunderous but somehow mocking voice of Azash booming hollowly from the temple and cheered by multitudes of howling fiends.

There began then a ghastly reign of terror in Zemoch. All opposing cults were ruthlessly extirpated. Sacrifices of the newborn and virgins numbered in the thousands, and Elene and Styric alike were converted by the sword to the worship of Azash. It took perhaps a century for Otha and his henchmen to totally eradicate all traces of decency from his enslaved subjects. Blood-lust and rampant cruelty became common, and the rites performed before the altars and shrines erected to Azash became increasingly degenerate and obscene.

In the twenty-fifth century, Otha deemed that all was in readiness to pursue the ultimate goal of his perverted God, and he massed his human armies and their dark allies upon the western borders of Zemoch. After a brief pause, while he and Azash gathered their strength, Otha struck, sending his forces down onto the plains of Pelosia, Lamorkand and Cammoria. The horror of that invasion cannot be fully described. Simple atrocity was not sufficient to slake the savagery of the Zemoch horde, and the gross cruelties of the inhumans who accompanied the invading army are too hideous to be mentioned. Mountains of human heads were erected, captives were roasted alive and then eaten, and the roads and highways were lined with occupied crosses, gibbets and stakes. The skies grew black with flocks of vultures and ravens and the air reeked with the stench of burned and rotting flesh.

Otha’s armies moved with confidence towards the battlefield, fully believing that their hellish allies could easily overcome any resistance, but they had reckoned without the power of the Knights of the Church. The great battle was joined on the plains of Lamorkand just to the south of Lake Randera. The purely physical struggle was titanic enough, but the supernatural battle on that plain was even more stupendous. Every conceivable form of spirit joined in the fray. Waves of total darkness and sheets of multicoloured light swept the field. Fire and lightning rained from the sky. Whole battalions were swallowed up by the earth or burned to ashes in sudden flame. The shattering crash of thunder rolled perpetually from horizon to horizon, and the ground itself was torn by earthquake and the eruption of searing liquid rock which poured down slopes to engulf advancing legions. For days the armies were locked in dreadful battle upon that bloody field before, step by step, the Zemochs were pushed back. The horrors which Otha hurled into the fray were overmatched one by one by the concerted power of the Church Knights, and for the first time the Zemochs tasted defeat. Their slow, grudging retreat became more rapid, eventually turning into a rout as the demoralized horde broke and ran towards the dubious safety of the border.

The victory of the Elenes was complete, but not without dreadful cost. Fully half of the Militant Knights lay slain upon the battlefield, and the armies of the Elene Kings numbered their dead by the scores of thousands. The victory was theirs, but they were too exhausted and too few to pursue the fleeing Zemochs past the border.

The bloated Otha, his withered limbs no longer even able to bear his weight, was borne on a litter through the labyrinth at Zemoch to the temple, there to face the wrath of Azash. He grovelled before the idol of his God, blubbering and begging for mercy.

And at long last Azash spoke. ‘One last time, Otha,’ the God said in a horribly quiet voice. ‘Once only will I relent. I will possess Bhelliom, and thou wilt obtain it for me and deliver it up to me here, for if thou dost not do this thing, my generosity unto thee shall vanish. If gifts do not encourage thee to bend to my will, perhaps torment will. Go Otha. Find Bhelliom for me and return with it here that I may be unchained and my maleness restored. Shouldst thou fail me, surely wilt thou die, and thy dying shall consume a million, million years.’

Otha fled, and thus, even in the ruins and tatters of his defeat was born his last assault upon the Elene kingdoms of the west, an assault which was to bring the world to the brink of universal disaster.

Chapter 1

The waterfall dropped endlessly into the chasm that had claimed Ghwerig, and the echo of its plunge filled the cavern with a deep-toned sound like the after-shimmer of some great bell. Sparhawk knelt at the edge of the abyss with the Bhelliom held tightly in his fist. Thought had been erased, and he could only kneel at the brink of the chasm, his eyes dazzled by the light of the sun-touched column of water falling into the depths from the surface above and his ears full of its sound.

The cave smelled damp. The mist-like spray from the waterfall bedewed the rocks, and the wet stones shimmered in the shifting light of the torrent to mingle with the last fading glimmerings of Aphrael’s incandescent ascension.

Sparhawk slowly lowered his eyes to look at the jewel he held in his fist. Though it appeared delicate, even fragile, he sensed that the Sapphire Rose was all but indestructible. From deep within its azure heart there came a kind of pulsating glow, deep blue at the tips of the petals and darkening down at the gem’s centre to a lambent midnight. Its power made his hand ache, and something deep in his mind shrieked warnings at him as he gazed into its depths. He shuddered and tore his eyes from its seductive glow.

The hard-bitten Pandion Knight looked around, irrationally trying to cling to the fading bits of light lingering in the stones of the Troll-Dwarf’s cave as if the Child-Goddess Aphrael could somehow protect him from the jewel he had laboured so long to gain and which he now strangely feared. There was more to it than that, though. At some level below thought Sparhawk wanted to hold that faint light forever, to keep the spirit if not the person of the tiny, whimsical divinity in his heart.

Sephrenia sighed and slowly rose to her feet. Her face was weary and at the same time exalted. She had struggled hard to reach this damp cave in the mountains of Thalesia, but she had been rewarded with that joyful moment of epiphany when she had looked full into the face of her Goddess. ‘We must leave this place now, dear ones,’ she said sadly.

‘Can’t we stay a few minutes longer?’ Kurik asked her with an uncharacteristic longing in his voice. Of all the men in the world, Kurik was the most prosaic – most of the time.

‘It’s better that we don’t. If we stay too long, we’ll start finding excuses to stay longer. In time, we may not want to leave at all.’ The small, white-robed Styric looked at Bhelliom with revulsion. ‘Please get it out of sight, Sparhawk, and command it to be still. Its presence contaminates us all.’ She shifted the sword the ghost of Sir Gared had delivered to her aboard Captain Sorgi’s ship. She muttered in Styric for a moment and then released the spell that ignited the tip of the sword with a brilliant glow to light their way back to the surface.

Sparhawk tucked the flower gem inside his tunic and bent to pick up the spear of King Aldreas. His chain-mail shirt smelled very foul to him just now, and his skin cringed away from its touch. He wished that he could rid himself of it.

Kurik stooped and lifted the iron-bound stone club the hideously malformed Troll-Dwarf had wielded against them before his fatal plunge into the chasm. He hefted the brutal weapon a couple of times and then indifferently tossed it into the abyss after its owner.

Sephrenia lifted the glowing sword over her head, and the three of them crossed the gem-littered floor of Ghwerig’s treasure cave towards the entrance of the spiralling gallery that led to the surface.

‘Do you think we’ll ever see her again?’ Kurik asked wistfully as they entered the gallery.

‘Aphrael? It’s hard to say. She’s always been a little unpredictable.’ Sephrenia’s voice was subdued.

They climbed in silence for a time, following the spiral of the gallery steadily to the left. Sparhawk felt a strange emptiness as they climbed. They had been four when they had descended; now they were only three. The Child-Goddess, however, had not been left behind, for they all carried her in their hearts. There was something else bothering him, though. ‘Is there any way we can seal up this cave once we get outside?’ he asked his tutor.

Sephrenia looked at him, her eyes intent. ‘We can if you wish, dear one, but why do you want to?’

‘It’s a little hard to put into words.’

‘We’ve got what we came for, Sparhawk. Why should you care if some swineherd stumbles across the cave now?’

‘I’m not entirely sure.’ He frowned, trying to pinpoint it. ‘If some Thalesian peasant comes in here, he’ll eventually find Ghwerig’s treasure-hoard, won’t he?’

‘If he looks long enough, yes.’

‘And after that it won’t be long before the cave’s swarming with other Thalesians.’

‘Why should that bother you? Do you want Ghwerig’s treasure for yourself?’

‘Hardly. Martel’s the greedy one, not me.’

‘Then why are you so concerned? What does it matter if the Thalesians start wandering around in here?’

‘This is a very special place, Sephrenia.’

‘In what way?’

‘It’s holy,’ he replied shortly. Her probing had begun to irritate him. ‘A Goddess revealed herself to us here. I don’t want the cave profaned by a crowd of drunken, greedy treasure-hunters. I’d feel the same way if someone profaned an Elene Church.’

‘Dear Sparhawk,’ she said, impulsively embracing him. ‘Did it really cost you all that much to admit Aphrael’s divinity?’

‘Your Goddess was very convincing, Sephrenia,’ he replied wryly. ‘She’d have shaken the certainty of the Hierocracy of the Elene Church itself. Can we do it? Seal the cave, I mean?’

She started to say something, then stopped, frowning. ‘Wait here,’ she told them. She leaned Sir Gared’s sword point up against the wall of the gallery and walked back down the passage a little way, and then stopped again at the very edge of the light from the glowing sword-tip where she stood deep in thought. After a time, she returned.

‘I’m going to ask you to do something dangerous, Sparhawk,’ she said gravely. ‘I think you’ll be safe though. The memory of Aphrael is still strong in your mind, and that should protect you.’

‘What do you want me to do?’

‘We’re going to use Bhelliom to seal the cave. There are other ways we could do it, but we have to be sure that the jewel will accept your authority. I think it will, but let’s make certain. You’re going to have to be strong, Sparhawk. Bhelliom won’t want to do what you ask, so you’ll have to compel it.’

‘I’ve dealt with stubborn things before,’ he shrugged.

‘Don’t make light of this, Sparhawk. It’s something far more elemental than anything I’ve ever done before. Let’s move on.’

They continued upward along the spiralling passageway with the muted roar of the waterfall in Ghwerig’s treasure-cave growing fainter and fainter. Then, just as they moved beyond the range of hearing, the sound seemed to change, fragmenting its one endless note into many, becoming a complex chord rather than a single tone – some trick perhaps of the shifting echoes in the cave. With the change of that sound, Sparhawk’s mood also changed. Before, there had been a kind of weary satisfaction at having finally achieved a long-sought goal coupled with the sense of awe at the revelation of the Child-Goddess. Now, however, the dark, musty cave seemed somehow ominous, threatening. Sparhawk felt something he had not felt since early childhood. He was suddenly afraid of the dark. Things seemed to lurk in the shadows beyond the circle of light from the glowing sword-tip, faceless things filled with a cruel malevolence. He nervously looked back over his shoulder. Far back, beyond the light, something seemed to move. It was brief, no more than a flicker of a deeper, more intense darkness. He discovered that when he tried to look directly at it, he could no longer see it, but when he looked off to one side, it was there – vague, unformed and hovering on the very edge of his vision. It filled him with an unnamed dread. ‘Foolishness,’ he muttered, and moved on, eager to reach the light above them.