Полная версия

Odd Girl Out

Odd Girl Out

Ann Bannon

www.spice-books.co.uk

Table of Contents

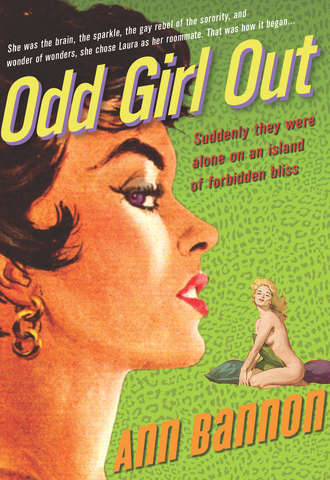

Cover

Title Page

Introduction: The Beebo Brinker Chronicles

The Beginning …

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Endpages

Copyright

Introduction: The Beebo Brinker Chronicles

I must have been the most naïve kid who ever sat down at the age of twenty-two to write a novel. It was the mid-1950s. Not only was I fresh from a sheltered upbringing in a small town, I had chosen a topic of which I had literally no practical experience. I was a young housewife living in the suburbs of Philadelphia, college graduation just months behind me, and utterly unschooled in the ways of the world. There were millions living the same life; I was to be indistinguishable from them for many years, except for the fact, known to very few outside my immediate family, that I was the one who wrote a series of lesbian pulp paperback novels under the pen name of Ann Bannon. The stories came to be known as The Beebo Brinker Chronicles.

To my continuing astonishment, the books have developed a life of their own. They were born in the hostile era of McCarthyism and rigid male/female sex roles, yet still speak to readers in the twenty-first century, giving them an historical snapshot of the times. They have been revived in editions by five different publishers, once even coming out in a hard cover library edition. They have given comfort and courage to young gay people exploring their often difficult identities. They have even dismayed some in that community in our own time for their depiction of the stereotypes of the 1950s.

I sometimes shake my head and wonder, Who was that ingenuous twenty-two-year-old to be making these bold observations? Was she really me? Do I even know her anymore? Yes. She was me and I still recognize her. And I recall the characters I created, too. There they are in the pages written all those years ago: the girls I found so beguiling in college, the young women I met coming to the big city for the first adult adventures of their lives. In them, I still see the perplexities of identity, so pressing in youth, buried just beneath the sexual urgencies that drove us all. I see the older women, too, a little weary, a lot wary, many of them not that far in time from the utmost upheaval in their lives: World War II.

The world in the 1950s was changing in ways that were to lead inexorably to the Civil Rights Movement, the Women’s Movement, and yes, the Gay Rights Movement.

But those great social temblors were still in the future when I got my first look at a tranquil, almost rustic, Greenwich Village, with its parks, its crooked streets, its crafts shops, and its beckoning gay and lesbian bars. It was love at first sight. Every pair of women sauntering along with arms around waists or holding hands was an inspiration. As I’ve often remarked, I felt like Dorothy throwing open the door of the old gray farm house and viewing the Land of Oz for the first time.

At that time, I was bubbling with stories of young arousal, but woefully lacking in what might be called “fieldwork experience.” I started to tell the story of a college sorority friend, heavily disguised of course, whose sexuality I suspected and who had aroused feelings in me that I both feared and enjoyed. I wanted to tell her story, and by telling hers to explore my own. I had absolutely no idea that I was on the cutting edge of anything, that I was about to catch a wave, or that others beside myself were engaged in similar creative tasks. I had read just two lesbian novels in my life: Radclyffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness and Vin Packer’s Spring Fire.

It was to Vin Packer, then living and writing in New York, that I wrote with an appeal to help me get started. For her own reasons, she was kind enough to invite me to bring the unwieldy first draft of Odd Girl Out to New York. She would introduce me to her editor at Gold Medal Books, a major publisher of original pulp novels in the 1950s and 60s. The editor, Dick Carroll, took the book in hand. Within three days, he had read the manuscript. I waited in his office to hear the verdict.

“It’s pretty bad,” he said gently. “But I think it’s fixable. Go home, put this manuscript on a diet, and tell the story of the two girls. Then send it back to me.”

“The two girls?” Beth and Laura; I was dumbfounded. They had been no more than a distraction in the original story, based on girls I had known and admired in my college sorority. I was abashed to learn that my subtle little subplot had the makings of a novel, but all the other verbiage—what I had thought of as the novel—was smothering it.

I did go home, I did squeeze the story in half, I did write about Beth and Laura, amazed at the easy flow of the words. And months later, when Dick Carroll read it again, he published it, without changing a single word—without, in fact, even adding the word “lesbian,” which I had only just added to my vocabulary. It was not until thirty years later that I discovered that Odd Girl Out had been the second best-selling paperback book of 1957. I was off and running.

But how to follow up? Well, one writes what one knows. When I wrote Odd Girl Out, I knew college life. Now, I was determined to learn about gay life. New York was the focus of gay and lesbian culture in those days; it was electrifying to be there, even though my visits were necessarily brief, stolen from a conventional housewifely routine in Philadelphia. Once again, it was Vin Packer who helped me out and showed me around the Village; I will always be grateful for her help. I made the most of every moment. I visited every bar I could, and I got acquainted with some wonderful people. I walked the streets for hours, soaking it all up. On one occasion, I even walked home alone from a club at two in the morning. Such is the psychological armor of a twenty-two-year-old that I hadn’t the sense to be scared. I fully, frankly loved and embraced the Village.

But for all the exhilaration of these stolen moments, it was scary to write about lesbianism in the 1950s, the era of government repression, confining bias, and rigid social roles. I even worried that the FBI might be keeping a file on me. How did we get away with it, those of us writing these books? No doubt it had a lot to do with the fact that we were not even a blip on the radar screens of the literary critics. Not one ever reviewed a lesbian pulp paperback for the New York Times Review of Books, the Saturday Review, The Atlantic Monthly. We were lavishly ignored, except by the customers in the drugstores, airports, train stations, and newsstands who bought our books off the kiosks by the millions. The readers tended to enjoy them furtively; probably feeling as wary as I did when I wrote them. There was no public dialog about them in the media, either on their literary merits or their content, and that benign neglect provided a much-needed veil behind which we writers could work in peace.

And this had its benefits. Escaping public scrutiny as we did, we had a chance to talk about things that other writers usually handled—if they approached them at all—with a pair of tongs. We could take chances, we could be subversive, we could look at all the shameful, seductive, irresistible, delightful appeal of “the sex that dared not speak its name.” In a way, we were daredevils, protected by our unknown, uncredited, unsung noms de plume.

It took guts just to buy those books and confront the smirk on the face of the clerk at the cash register. People tried to disguise them in a pile of sundries they probably didn’t even need but bought anyway to distract attention from those eye-popping covers. I know—I was buying them, too. But once they had purchased them, they took the books home, read and re-read them, cherished them, and then hid them behind the fridge, in shoe boxes in their closets, under mattresses. It was a life-changing event if a spouse, a parent, or even a child found the books and challenged the reader. Nobody wanted to be shoved unceremoniously out of the closet, ready or not, particularly in that unforgiving time. But it did happen to many readers back then.

In Jaye Zimet’s book, Strange Sisters: the Art of Lesbian Pulp Fiction, 1949-1969 (Penguin, 1999), for which I wrote the foreword, the colorful cover art for the lesbian pulps is given a showcase. Looking it over, I’m moved to wonder: How strange were our sisters? Even in the “exotic” and distant 1950s? Not very, truth to tell. Wonderful, but not strange, or at least, strange only on the covers of the books. When I was writing about them, I thought they were brave, passionate, gorgeous, and very, very cool. But not strange. And yet that word figures in dozens of the paperback book titles of the period as a sort of code for lesbian content, recognized by male and female readers alike.

Webster’s defines “pulp” as “tawdry or sensational writing.” In other words, sleaze. It never entered my head that I was writing sleaze; I was writing romantic stories of women in love. But it certainly entered the heads of the editors and publishers of the original pulps, and in a far from negative sense. Their job was to promote, market, and sell the books, and sleaze had a huge appeal. Furthermore, being men—most of them, anyway—they knew that the cover tease, showing a couple of desirable women who presumably would have interesting sex in the story, would lure a male audience and probably double their profits. Women readers could be relied on to read the covers iconically; men read them literally. Both would buy the books.

So the paperback publishers made money in what was basically the trashy trailer park of literature by lavishing curvy girls, lacy underwear, and heavy suggestions of sin and excess on their covers. That this frequently had little or no relationship to the actual characters and events in the stories was seldom a concern, any more than were the requests of the authors themselves with regard to cover illustration.

Neither were we consulted on the titles. I can remember tearing open the brown paper packages in which complimentary copies of my novels would arrive, and bracing myself for the shock of the cover art and, on occasion, even the title. The blurbs were lubriciously inventive: “The Savage Novel of a Lesbian on the Loose.” “They came to college sweet, pretty, and unsuspecting. But the house mother was strangely corrupt …” “Mary lacerated the flesh of a hundred girls with her searing caresses.” “The world of the third sex … that land of strange loves and rapacious passions.” “It was hard to figure out who was male and who was female … sometimes they were interchangeable.” “She found herself climbing down a ladder of flesh into a cesspool of Lesbian depravity.” With blurbs like these, who needed the critics’ praise to sell books? They flew off the shelves. And still nobody in the wider world took notice except the readers themselves.

Then the letters started pouring in. Those from the men were often propositions; those from the women were cries of the heart. The female readers wrote from little towns all over the country. Such was their isolation that many of them were grateful to me for reassuring them that they were not totally alone in the world. They wanted me to tell their stories, they wanted me to give them advice, and they wanted to meet me. They were sweet, tentative, grateful, scared, and even needier than I, if that’s possible, of education and support.

I wish I had those letters still—they were lost in one of many moves over the years. They would astonish the far more knowledgeable readership of women today in their ingenuousness, their yearning, their sense of exile, but with it all, their good humor, their sheer guts and perseverance. These women lived in a world where they thought themselves to be painfully unique. The bottom line was, they imagined themselves doomed to solitude in their yearnings for the rest of their lives and sadly, deservedly so, since they had no positive role models to contradict such self-prejudice. I admired and even loved them, although I only ever met one of them, through her personal determination to make it happen. I often think of them and hope their lives turned out better than they could then have known or dared to hope.

But these letters overwhelmed me. What to tell them? I was being appealed to for help as if I were a lesbian Ann Landers. Little did they know it was a case of the blind leading the blind. What could I, in my naiveté, possibly say that would help them through their sexual exile, give them warmth and hope? The only gift I could give back to these readers was another story.

In my visits to Greenwich Village, I had already learned to recognize the butch/femme dichotomy so influential at the time, and I wanted to write a book about a big, handsome, exasperating, reckless, bright, funny, irresistible butch. She would do what I could not. She would be what I could not. I already knew her in the theater of my mind, and I even knew her name: Beebo Brinker. I stole the “Beebo” from a childhood friend who couldn’t pronounce her given name of Beverly. The “Brinker” was my own inspiration. She was never modeled on a real woman, although several were influential in various ways. Instead she sprang like Minerva from my brow, propelled to life by the twin engines of fantasy and need.

When Beebo was at her buccaneer best, I was infatuated with her myself. When she was at her destructive worst, I was using her as a dumping ground for my own frustrations. She was tough and could take it, and made my life better and my spirit stronger by shouldering the troubles I couldn’t resolve. But it resulted in giving her a dark side I now wish I could soften.

I gave at least some of the stories a happy ending, sort of. Nobody had to be shot or jump in front of a train for the sin of loving another woman. Bad things did happen that reflected the arrogant ignorance of the authorities, the contempt of conventional society, and the occasional desperation of the women of the times; modern readers may feel impatient with some of this now, but it was part of life back then. But still there was humor and there was love, in at least as good measure, and I am most proud of having captured some of that temper of the times as well.

I had no idea I was being brave or daring when I started writing, so perhaps it doesn’t count. But after Odd Girl Out was published and I realized I was, I kept on writing anyway, so perhaps it does. One of the hardest things I ever had to do was hand a copy of the first edition of Odd Girl Out to my mother to read. It’s the one that shows the author’s name as “A. Bannon.” I was too shy then even to let my first name be printed on the cover. My mother was a strikingly pretty and spirited lady, whose beauty and willfulness had gotten her into three marriages and many scrapes. But for all that, she was raised by my little Victorian grandmother, who steeped her in the manners required of nice girls. It was part of the code that a lady simply sailed past unpleasantness wherever possible, taking no note of it.

My mother read the book and I waited for the toughest review of my life. As I waited, I thought of what must be going through her mind: all those home-movie recollections of a quirky little girl with a passion for books and music, cautious with new friendships, reassuringly like her age-mates to the eye but disturbingly intense and eccentric in other ways. Still, there was nothing in her memories to prepare her for what she was reading. It must have been breathtaking. She, of course, would never say so. I think she took courage from the fact that I was then a pretty young housewife and mother. Things couldn’t be too far off track. And besides, I was her daughter; she was going to support me if she could. Finally, she put the book down and said thoughtfully, “Sweetheart … I didn’t know you had it in you.” And then, because I was hers, and I had done something difficult in writing a book and getting it published, she added, “I’m proud of you.” I started breathing again. “But,” she added, “don’t ever show this to your grandmother.” I never did.

Perhaps it is only fair to mention the husband who played so minimal a role in Ann Bannon’s existence but so great a role in mine. He was aware of the general theme of the books, but it interested him not at all. The royalty checks, however, did. I think for that reason and others of his own, he did not try to discourage me. He read no more than a few paragraphs of Odd Girl Out, and that was enough for him. He was a basically good person; he meant well and he loved me, and I will not lay all the blame for my grief in that marriage at his feet. Suffice it to say that I have never regretted its ending, and am grateful to leave it at rest in the past. My children are now beautiful and successful adults, so there was a magnificent reward for the difficult years.

Why didn’t I stay in Greenwich Village when I had the chance? Why didn’t I break out of wedlock? Well, this was 1956. I was twenty-two and while I had a college education, it was ornamental; I had no marketable skills. I was also very much my mother’s child. In our family there was a grand tradition of soldiering through in the traditional role, whatever the challenges. My mother had done it and her mother before her. They were both very much alive and I was not going to let them down. This was familiar territory; better the shackles of the known than the terrors of the new and unfathomable.

Perhaps, also, I was just plain scared to assume an identity that seemed to me full of mystery, one which I was just beginning to recognize and understand. It had been clear to me from my earliest memories that I was not going to be like the other children I knew. Nobody else among my classmates had fallen secretly in love with the Statue of Liberty. I did, because she was the biggest, most beautiful, most powerful image of womanhood I had ever seen. Nobody else was in love with the picture of Mozart on our music books. I was, because he looked to me, with his delicate features and long hair, like a child magically suspended between the sexes.

I also had a fully reasonable fear of the public consequences. God forbid that a policeman should ever pluck me from a table in a lesbian bar, shove me into a paddy wagon, and put my name on the roster of criminals. The bars underwent regular police raids in those days, and if you were visiting one that hadn’t been hit for a couple of months, you were in peril.

Nor could I face the prospect of having my children snatched from me. When you get down to cases, I and many other women feared that most of all. Lesbians were an illegal social category—not really yet a community—with no right to exist. Furthermore, if you were tagged with the lesbian label, you were typed beyond any hope of revealing yourself as a human being in full. Knowing you were gay, people thought they knew all there was to know about you, and what there was to know about you was that you were contaminated. There was a scarlet letter “L” on your chest. It was an age when homosexuality was a disease and stereotyping ran roughshod over real human beings. The women who came out under this kind of fire and, in effect, told the Establishment to stuff it are my heroes.

As for me, I went another way. I thought I could simply continue to live in my imagination, could use writing as a pressure valve when things got too difficult. This I did through six novels, writing in hours stolen from the relentless tasks of running a household and raising my children, so I could spend time with Laura, Beth, Beebo and the others. You’ve heard of fantasy friends; they were mine.

And then … I stopped writing. For some reason, that run of incredible emotional energy flamed out. It’s never been entirely clear to me why, but I actually felt emptied of stories for a while. It was a period in my life when my children needed a lot from me, we were moving frequently, and what strength I had was concentrated on a deteriorating marriage. I wanted to feed my mind on something absorbing, something that would take me out of myself. When Lord Byron’s friends asked him why in the world he had taken up the study of Armenian, he replied, “I found that my mind wanted something craggy to break upon.” That is just how it felt—something tough enough to distract me from the problems in my life for which I could see no resolution.

So I went back to graduate school. I earned a teaching credential, a master’s degree, and ultimately, a doctorate. It was an undertaking that consumed a whole decade from the mid-60s to the mid-70s, and led me to a position as a college professor, then a program director, and finally, an assistant dean in the university where I pursued my academic career. I did a lot of writing, of course, but it was all academic papers, memos, study materials, and professional letters. Ann Bannon had ceased to exist; she had become a phantom of my surprising past, almost as much a fictional character as Beebo Brinker herself. I thought I would never return to her, that no one knew she had ever had a life or written a word. The Greenwich Village of the 1950s and 60s had never seemed so far away.

And then the unimaginable happened. The New York Times publishing branch, Arno Press, wrote to me. They wanted permission to include four of my books in a library edition of gay and lesbian literature, under the rubric Homosexuality: Lesbians and Gay Men in Society, History and Literature. It was the first hint I had that Beebo Brinker and her creator had earned a life of their own.

I gratefully accepted the offer from the Times, and the hardcover edition was duly published. That, I thought, must be that; it was a sort of fluke. There was a glimmer of interest in the books as vignettes of a bygone time; indeed, in Ann Bannon herself as a sort of historical artifact. But the wave subsided. Several years went by, during which my children entered college, my long and difficult marriage ended, and my university career prospered.

And then it happened again. I was alone for the first time in my life in the early 1980s, living in a rental townhouse, when the telephone rang at a severely early hour one morning. It was Barbara Grier of Naiad Press, calling from Tallahassee, Florida. She had gotten my name from the people at Arno Press and tracked me down. I remembered Barbara’s name from the years when I was avidly reading any copies of The Ladder that I could get my hands on, and she was editing it as Gene Damon; I remembered reading about a bibliography of lesbian literature she had compiled, but I had never seen it. The name of the Naiad Press was entirely new to me.

But not for long. Barbara and her partner, Donna McBride, wanted to bring out the five books which had to do with Laura, Beth, and Beebo. It was my first inkling that my stories had been valued and preserved by a whole generation of women; that despite the crumbling condition of the old pulp paper and fading ink, they had survived on many bookshelves in many homes.