Полная версия

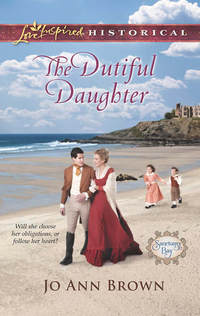

Promise of a Family

Drake was pleased. Even a year ago, Benton would not have comprehended the tough decisions a captain had to make. The young first mate would soon be ready to take over his own ship. Drake would miss Benton’s willingness to tackle any job and his good rapport with the men.

Clapping his mate on the back, he said, “Let’s get to work.”

“Aye, Captain.” He hurried to the hatch and down to the lower decks.

Drake started to follow, but again his gaze focused on the grand house beyond the village. He looked away. There was nothing there for him, but he could not keep from wondering how Lady Susanna and the children fared now that a few days had passed.

Less than two hours later, his curiosity overmastered his good judgment. He was admitted to the great house as soon as he reached its door, and a footman offered to take him to where he could speak with Lady Susanna. The footman led the way up one grand staircase and then along a long hallway decorated with paintings of people who must be Lady Susanna’s ancestors. He could not imagine being surrounded by so much history of generations past. After all, he had known neither his father nor his mother, for they had abandoned him in a neighbor’s care soon after his birth. He had found his first true family when he signed on a trading ship as cabin boy.

“This way, Captain Nesbitt,” said the footman in his light gray livery that did not have a single piece of lint on it. He began up a narrow stairwell.

Drake followed, uncertain where they were bound. He had been in great houses once or twice, but never beyond the public rooms, so he had no idea what to expect when they reached the top of the steps.

It was as if they had entered a different house. An odor of dampness and neglect filled each breath he took. No thick carpets covered the wide floorboards that needed to be restained. The walls were bare, though he could see the shadowed outlines where pictures had hung between doors. They were closely spaced, so the rooms beyond them must be not much bigger than his quarters on The Kestrel. A few tables were pushed against the walls. All were either scratched or chipped.

As they left the double row of doors behind and walked along a blank wall where paint peeled off in long strips, voices emerged from a doorway at the far end of the hallway.

A man said, “The first thing we need is a good nursery staff.”

“No,” replied a female voice. “I believe you are mistaken on this.”

Even if Drake had not recognized the melodious tone, he could identify Lady Susanna by her poised, self-assured words.

“The first things we need,” she went on, “are uncracked windows and fresh paint on the walls. I doubt if anyone has been up here since the nursery was closed.”

“Making all those repairs will take time and money. I doubt we can get the windows replaced in less than a month or more. By that time, the children will be back with their families.”

“I hope you are right.” A hint of humor warmed her voice. “In that case, you can see it as early preparations for your heir, Arthur.”

The footman stepped into the doorway and announced, “My lord, my lady, excuse my intrusion. Captain Nesbitt is here and wishes to speak with you, my lady.”

“Tell him,” Lady Susanna said, “that I will be with him shortly. Thank you, Venton. Arthur, I am sure we can complete the nursery quickly if we put our minds to it.”

“My lady, Captain Nesbitt—”

“I heard you, Venton. That will be all.”

The footman cleared his throat and said, “My lady, Captain Nesbitt is here.”

Drake stepped forward. He scanned the room. It was in as bad repair as the corridor, but shelves still contained carefully packed boxes that might contain toys or clothing or even books. He struggled to imagine how anyone could leave books in a damp room. He owned one book, a well-read copy of Robinson Crusoe, and he kept it carefully wrapped in oilcloth in his quarters.

“So I see,” said the man who had been conversing with Lady Susanna. He had her ebony hair and high cheekbones. He affixed Drake with an icy stare.

Drake met it steadily. He might not be the heir to an earldom, but he had information of import for Lady Susanna.

His supposition was confirmed when she said, “Arthur, allow me to introduce you to Captain Nesbitt. Captain, this is my older brother, Lord Trelawney.”

Even though he hated to be the first one to look away, Drake could not halt his gaze from shifting to Lady Susanna. He realized he had been avoiding looking in her direction. Rightly so, because a single glance at her stole his breath away.

She was dressed in a simple pale blue gown that was covered by a gray apron. Her hair was piled up carelessly on her head. A few strands had escaped to curve along her left cheek, and he had to clench his hands at his sides to keep from reaching out to brush those tresses back along her face. A streak of dust shadowed her right eye.

“My lord,” he said, offering his hand.

Lord Trelawney seemed astonished, but shook Drake’s hand. “I will leave you to make plans for the children.”

“Arthur, we need to discuss further repairs to the nursery.” Lady Susanna frowned.

“I will study the list in the morning. As for now, if you need anything, Venton will be here to assist you.”

Drake understood Lord Trelawney’s true message to his servant. The footman would make sure that nothing untoward happened. The urge to laugh tickled the back of Drake’s throat. Lady Susanna hardly needed a chaperone. She could freeze a man in place with a single look.

As soon as Lord Trelawney took his leave, Venton moved to stand just inside the doorway. The spot gave him a clear view of the main room and a smaller one beyond it.

“I thought you had taken your leave of Porthlowen,” Lady Susanna said.

“When I did not return?”

“Yes.”

He shook his head. “Unfortunately, there is still more work to be done on The Kestrel. And, if you remember, I told you that as long as I am in Porthlowen, I would do what I could to help the children. How are they?”

Her shoulders eased from their rigid stance, and an honest smile brightened her face. “Better than I dared to hope. The twins and Bertie have become inseparable. They are fun and funny. My sister is caring for Gil and the baby she’s named Joy, because she is such a happy child.”

“And Toby? Are he and Bertie still quarreling with each other?”

“Toby lives with my brother at the parsonage. We thought giving the boys some time apart would be wise. From what Raymond tells us, Toby has charmed most of the older ladies in the parish, especially Hyacinth and Ivy Winwood, who have made plenty of excuses to call at the parsonage.” She hesitated, kneading her fingers together, then asked, “Have you come because you have news about the search for the children’s families?”

He nodded, and color washed from her face. Was she fearing that he had found the children’s parents or that he had not? True affection had been laced through her words as she spoke of them.

The spot beneath her eye looked even darker, and he frowned as he caught her chin gently and tilted her face toward the light streaming in through the cracked window. He ignored the growled warning from Venton. He drew in a sharp breath of his own when he saw the puffiness beneath the darkness near her eye. It was not dirt. It was a bruise. She had been struck.

“Who darkened your daylight, my lady? Tell me the cur’s name, and I will make him regret being so discourteous to you.”

She drew away and laughed, wincing when her eyes crinkled in amusement. “I appreciate your chivalry, but Miss Mollie gave me this black eye.”

“One of the twins? But how...?”

“We were playing, and she flung her head back. I did not move swiftly enough. You see the result.”

“Maybe I should invite her to join my crew. She could come in handy if French privateers try to board us again.” He glanced over his shoulder at Venton, who was listening with sudden interest. Hadn’t the tale of The Kestrel’s battle been told and retold throughout Porthlowen? Apparently the footman had not heard of it before or wanted more details.

“What have you discovered about the children, Captain?” Lady Susanna asked.

“I sent men along the shore as far north as Trevana and as far south as Land’s End. No one they spoke to had heard that six children were missing. Or at least nobody would admit they had.”

She gave a terse laugh. “Captain, even if the children’s parents refused to step forward and own up to what they have done, others would notice children had gone missing. A single child might be hidden from neighbors until it was placed in the boat, but not six.”

“Then we will continue looking. I can send men across the moors to Penzance and Truro. Even as far as Looe, if necessary.”

She walked toward the shelves, her skirts whirling dust behind her. Running her fingers along the shelves, she wrinkled her nose when she looked at the dust on them. She slapped her hands together to clean them. The sound echoed in the empty room as she faced him.

“Maybe we are looking in the wrong place,” she said.

“It is unlikely they came from beyond Cornwall. Devon or Wales is a great distance for a jolly boat to travel.”

“But not a ship.”

He was puzzled. Usually his mind could keep up with any conversation. It might be that he was paying too much attention to the sway of her skirts as she walked toward him.

“A ship, Captain Nesbitt,” she said. “A ship can easily sail from Devon or Wales or even much farther away, as you know.”

“You need not instruct me about sailing, my lady, but I would appreciate if you could enlighten me about what exactly you are talking about.”

Her cheeks went from pale to flushed in a heartbeat. Her voice became as glacial as her brother’s. “Let me put it simply. French privateers attacked The Kestrel. You halted them, Captain, but maybe another ship was not so fortunate.”

What she was trying to tell him shot like a ball through his brain. Why had he failed to see that possibility himself? He had told her, after all, that they could not discount any theory until they were certain it would not lead to the children’s families.

“I will have my men make inquiries about missing ships as well as missing children,” he said.

“Good.” She started to walk away again, and he knew he had been dismissed.

He did not move. “My lady?”

“Yes?” She kept walking.

“I hope your idea is wrong.”

She stopped but did not turn. “Why?”

“Because if it is correct...”

She spun to look at him with horrified eyes. “Please tell me that you are not about to suggest that their own parents put them in the boat.”

“No, because that is not how privateers work. They want the cargo and the ship. Once they board, the ship’s crew and passengers are doomed.” He closed the distance between them until she had to tilt her head back to look up at him. Raising his hand, he slipped the loose hair back behind her ear. He heard her breath catch, and his heart quickened like a ship driven by a gale.

It took all his willpower to ignore both her reaction and his own. His life was already too enmeshed with the events and people of Porthlowen, and he would be gone soon. But he could not leave without warning her of a truth he doubted she could imagine.

Wiping a bit of fluffy dust from her cheek, he held her gaze as he whispered, “If you are right, no ship and no port, including Porthlowen, may be safe.”

He was shocked when she pulled back with the calm smile that was beginning to annoy him. He knew that expression was aimed at covering up her true emotions because her fingers trembled. Because he had touched her or because of what he had told her?

As if she spoke of nothing more important than the color of the water in the cove, she said, “We have never been assured of safety in Porthlowen. Before the French, there were other pirates and raiders, as well as storms and droughts and sickness.”

“Very well. It seems you understand. Therefore, I will bid you a good evening, Lady Susanna.”

“Good evening, Captain.” She relented from her icy pose as she added, “I truly appreciate you bringing me the information your men have gathered. We are grateful for your continuing efforts.”

“I helped rescue those children. I would be coldhearted not to be concerned about their well-being.”

She nodded, and he wondered if she ever lost control of her tight hold on herself. Even when she had gasped at his touch on her cheek, she’d quickly reverted to her cool exterior.

Drake got his answer when her name was shouted from the hallway, and a maid burst into the nursery. The young woman’s eyes were wide with dismay as she cried, “My lady! It is Miss Lucy! She tumbled down the stairs and landed on her head. We cannot wake her.”

Alarm wiped all other emotion from Lady Susanna’s face as she pushed past him. He caught her arm, and she whipped around, fury now mixed with fear.

“Let me go!” she ordered.

“I will, but I am going with you so you don’t fall down the steps in your haste to get to her.”

She nodded. “Hurry! I need to be there when she regains her senses.”

He steered her out of the room past the maid and the footman, who exchanged worried glances. He knew their thoughts as surely as if they were his own.

What if the tiny girl never woke?

Chapter Four

The bedchamber was lit by only a single lamp, leaving shadows across the ceiling and huddled in the corners. At both windows, the draperies were pulled closed, even though night had claimed Porthlowen. Silence hung over the room, too heavy to be broken. The only sound was breathing from the grand tester bed set at one end of the large room. With the bed curtains pulled aside, a single person was cushioned by the thick mattress and pillows that were almost as big as she was.

Susanna sat beside the bed on a hard chair. Baricoat, as well as Venton and two other footmen, had offered to bring her an upholstered chair from another room. She had thanked them but declined. As hours passed and dawn neared, she feared a more comfortable chair would tempt her to give in to the cloying caress of exhaustion. Her back ached from slanting forward to lean her elbows on the covers, but she did not take her gaze from Lucy’s motionless body.

With her hands clasped, she had prayed the same wordless prayer since Captain Nesbitt had carried Lucy in and placed the little girl on the bed. Lucy had looked like a rag doll, limp and unresponsive. Surely God, who had watched over the children while in the jolly boat, would bring Lucy healing.

Through the night, while Susanna kept vigil by the bed, she had looked for any sign of returning consciousness. Lucy breathed slowly and shallowly as if asleep.

The doctor had been sent for immediately, and when Mr. Hockbridge came, Susanna watched him examine the little girl with gentle, capable hands. Mr. Hockbridge had taken over caring for the sick around Porthlowen the previous year. His father had been their longtime doctor, but a heart condition had forced him to step aside. The young man, whose white-blond hair was thinning, had studied in London. If there was anyone in Cornwall who could help Lucy, it would be Mr. Hockbridge.

He had left no powders other than willow bark to ease any pain Lucy felt when she awoke. His only instructions were to pray. Telling Susanna he would be back before midday and that she should send for him if the situation changed, he had bidden her a good night.

Caroline had stopped in several times. The first time, she mentioned how distraught Mollie was. Lucy’s twin had seen her sister tumble down the stairs. It had been Mollie’s cries that brought the servants running to discover what had happened.

Each time, Susanna had nothing new to tell her sister. Caroline promised to stop by again in a few hours and then went to offer what comfort she could to Mollie and the other children.

So the hours passed while Susanna sat by the bed and prayed for Lucy to open her eyes. She never shifted her gaze from the tiny form on the big bed.

When she heard soft footsteps in the gray light before dawn, Susanna paid them no mind. People had been coming in and out of the bedchamber during the night. They had cast worried glances at the bed before leaving without a word.

“Lady Susanna,” came Mrs. Hitchens’s low whisper, “forgive me for interrupting, but Captain Nesbitt wishes to know if there has been any change.”

Astonished, she glanced over her shoulder. “He has come back?”

“He never left, my lady.”

Unexpected tears filled her eyes. She had assumed that Captain Nesbitt had returned to his ship once he set Lucy on the bed as carefully as if she were made of glass. That he had remained touched her heart that was so fragile when she faced another tragedy. Maybe she had misjudged him, if he put aside his other duties to wait for news about a child he barely knew.

“May I give him a message, my lady?” Mrs. Hitchens prompted.

Susanna came to her feet, wincing as her back protested moving after being in one position for hours. “No, I will deliver it myself. Where is he?”

“In the drawing room.”

“Thank you.”

“My lady?” The housekeeper glanced toward the bed.

“No change.” She smiled sadly at Mrs. Hitchens, whose kind heart must be aching, too.

“Poor lamb. I will sit with her until you return.”

“If—”

“If there is any change at all, I will send for you immediately.”

Thanking the housekeeper again, Susanna went downstairs. The drawing room was to the right of the entry foyer, set past the stairs so the windows offered a beautiful view of the gardens on the hillsides rising toward the moor.

The room was nearly as dark as the bedchamber. She saw no one inside. Had Captain Nesbitt taken his leave or perhaps fallen asleep? That made no sense, because Mrs. Hitchens would not have dawdled bringing his message. She stifled a yawn and knew it would take her only seconds to surrender to sleep.

Going back into the hallway, she picked up a lamp and returned to the drawing room. The light spread before her, restoring color in the Aubusson rug. The red lines edging a pattern of white roses seemed overly bright. Out of the darkness appeared two chairs upholstered in red-and-white silk, followed by a matching settee. The elegant white marble hearth glittered in the lamplight.

The room was deserted.

She was about to call Captain Nesbitt’s name when she noticed the French window leading onto the terrace was ajar. Crossing the room, she set her lamp on a table. She opened the door wider and saw Captain Nesbitt leaning his hands on the back of a stone bench. There, he could see the village, the cliffs that curved toward each other in a giant C to protect the cove, and the sea.

“This is my favorite view,” she said as she walked out onto the stone terrace.

“I can see why your ancestors built this house here.” Slowly he faced her. “How is Lucy?”

“There is no change. If I did not know better, I would say she is sleeping. She looks so peaceful.”

“What did the doctor say?”

She sighed. “He said the only things we can do now are wait and pray.”

“Not the prescription I had hoped he would give.”

“Prayer is always the best prescription, Captain.”

He leaned against the bench and folded his arms over his chest. His strong jaw was covered in a low mat of black whiskers that only emphasized its stubborn lines. “I cannot disagree with that, but I have found the results are not always something you can count on.”

“You don’t believe in God?”

“Quite the opposite. I believe in Him. I simply don’t know if He believes in me.”

She stared at him. The night was receding as the sun rose over the eastern hills, but his eyes still were dark pools that she could not read. “I believe that He hears our prayers, especially the ones from our hearts, and I have been praying all night.”

“If prayer is the answer, it should come soon with the number of people praying for her. I have heard murmured prayers from every direction while I paced through the house.”

“And you, Captain? Have you been praying?” Again she wished she could read the expression hidden in his shadowed eyes.

“Yes, but I hope others have better luck than I in getting their prayers answered.”

“All prayers are answered.”

“You sound so sure.”

“I am.”

He turned his head to stare out at the sea. “I wish I could be.”

“All you need to do is have faith.”

“You make it sound so simple.” His terse laugh was laced with regret. “I have not found it to be.”

“Surely you have felt God’s presence in your life. What about when you were attacked by those privateers?”

“I thought The Kestrel and all its crew were bound for the bottom of the sea.” He smiled as she started to reply. “I know what you are going to say. That by the grace of God we survived, and you may be right, but in the middle of that battle, there was nothing but death and dying.”

Susanna pressed her hands to her abruptly roiling stomach, wishing she had never brought up the privateers. She did not want to think of death. She wanted to concentrate on life and how they could bring one small child out of a coma to embrace it.

A sob burst out of her before she could halt it. Putting her hands over her face, she wept, too tired to hold back her tears any longer. Her fear of not knowing what else she could do to help little Lucy pressed down on her.

Wide, gentle hands drew her against a wool coat that smelled of salt and fresh air off the water. Beneath the wool, a strong chest held a heart that beat steadily as she gripped his coat and released her fear and frustration.

When her last tears were gone, Susanna drew back and wiped her hand against her face. Captain Nesbitt held out a handkerchief. She hesitated and then took it, as embarrassment overwhelmed her. She had lost control of her emotions in front of this handsome man. How could she ever look at him again without thinking of his muscular arms around her, offering her comfort?

“I am sorry,” she whispered, staring at her feet. “I usually hold myself together better than that.”

“You have nothing to be ashamed of.”

“That is kind of you to say.”

He lifted his handkerchief out of her hand and dabbed it against her cheeks to catch a pair of vagrant tears. Bending so his eyes were level with hers, he said nothing. Now the shadows had been banished, she could see the emotions within his dark brown eyes. Raw, unabashed sorrow at the accident that had left Lucy senseless. He must be able to see the same in her own eyes, she realized, and she lowered them, not wanting to share such a private part of herself with a man who was barely more than a stranger.

She was unsure when the light touch of the handkerchief collecting her tears altered to slow, feathery strokes along her face. Quivers flitted along her like seabirds darting at the waves. In spite of herself, she raised her eyes to his again. The potent emotions in them had only grown stronger, and she wondered how long anyone could look into his eyes without becoming lost in them.

“My lady! Lady Susanna!” called a bellow from the house.

Susanna stepped away from Captain Nesbitt, one unsteady step and then another, as if waking from a dream. Had she fallen asleep on her feet? She would rather think that than believe she had intentionally stood so close to him, allowing him to caress her face with his handkerchief.

He placed his handkerchief beneath his coat as her name was shouted again.

“You might want to answer,” he said in an emotionless tone.

She wished her voice could be as calm, but it was not when she called that she was on the terrace.

Venton peered past the French windows. His eyes narrowed slightly when he saw she was not alone, but he said, “My lady! Come! Right away!”