Полная версия

Son of the Shadows

JULIET MARILLIER

Son of the Shadows

Book Two of the Sevenwaters Trilogy

To Godric, voyager and man of the earth;and to Ben, a true son of Manannán mac Lir

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

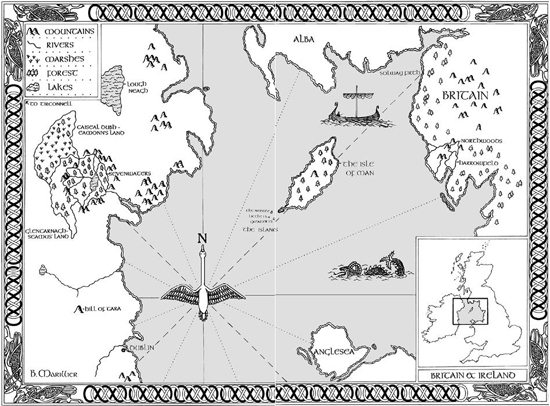

Map

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Author’s Note

Also by the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Map

Chapter One

My mother knew every tale that was ever told by the firesides of Erin, and more besides. Folk stood hushed around the hearth to hear her tell them, after a long day’s work, and marvelled at the bright tapestries she wove with her words. She related the many adventures of Cú Chulainn the hero, and she told of Fionn MacCumhaill, who was a great warrior and cunning with it. In some households, such tales were reserved for men alone. But not in ours; for my mother made a magic with her words that drew all under its spell. She told tales that had the household in stitches with laughter, and tales that made strong men grow quiet. But there was one tale she would never tell, and that was her own. My mother was the girl who had saved her brothers from a sorceress’ curse, and nearly lost her own life doing it. She was the girl whose six brothers had spent three long years as creatures of the wild, and had been brought back only by her own silence and suffering. There was no need for telling and retelling of this story, for it had found a place in folk’s minds. Besides, in every village there would be one or two who had seen the brother who returned, briefly, with the shining wing of a swan in place of his left arm. Even without this evidence, all knew the tale for truth, and they watched my mother pass, a slight figure with her basket of salves and potions, and nodded with deep respect in their eyes.

If I asked my father to tell a tale, he would laugh and shrug, and say he had no skill with words, and besides he knew but one tale, or maybe two, and he had told them both already. Then he would glance at my mother, and she at him, in that way they had that was like talking without words, and then my father would distract me with something else. He taught me to carve with a little knife, and he taught me how to plant trees, and he taught me to fight. My uncle thought that more than a little odd. All right for my brother Sean, but when would Niamh and I need skills with our fists and our feet, with a staff or a small dagger? Why waste time on this when there were so many other things for us to learn?

‘No daughter of mine will go beyond these woods unprotected,’ my father had said to my uncle Liam. ‘Men cannot be trusted. I would not make warriors of my girls, but I will at least give them the means to defend themselves. I am surprised that you need ask why. Is your memory so short?’

I did not ask him what he meant. We had all discovered, early on, that it was unwise to get between him and Liam at such times.

I learned fast. I followed my mother around the villages, and was taught how to stitch a wound, and fashion a splint, and doctor the croup or nettle rash. I watched my father, and discovered how to make an owl, and a deer, and a hedgehog out of a piece of fine oak. I practised the arts of combat with Sean, when he could be cajoled into it, and perfected a variety of tricks that worked even when your opponent was bigger and stronger. It often seemed as if everyone at Sevenwaters was bigger than me. My father made me a staff that was just the right size, and he gave me his little dagger for my own. Sean was quite put out for a day or so. But he never harboured grudges. Besides, he was a boy, and had his own weapons. As for my sister Niamh, you never could tell what she was thinking.

‘Remember, little one,’ my father told me gravely, ‘this dagger can kill. I hope you need never employ it for such a purpose; but if you must, use it cleanly and boldly. Here at Sevenwaters you have seen little of evil, and I hope you will never have to strike a man in your own defence. But one day you may have need of this, and you must keep it sharp and bright, and practise your skills, against such a day.’

It seemed to me a shadow came over his face, and his eyes went distant as they did sometimes. I nodded silently, and slipped the small, deadly weapon away in its sheath.

These things I learned from my father, whom folk called Iubdan, though his real name was different. If you knew the old tales, you recognised this name as a joke, which he accepted with good humour. For the Iubdan of the tales was a tiny wee man, who got into strife when he fell into a bowl of porridge, though he got his own back later. My father was very tall, and strongly built, and had hair the colour of autumn leaves in afternoon sun. He was a Briton, but people forgot that. When he got his new name he became part of Sevenwaters, and those that didn’t use his name called him the Big Man.

I’d have liked a bit more height myself, but I was little, skinny, dark haired, the sort of girl a man wouldn’t look twice at. Not that I cared. I had plenty to occupy me, without thinking that far ahead. It was Niamh they followed with their eyes, for she was tall and broad shouldered, made in our father’s image, and she had a long fall of bright hair and a body that curved generously in all the right places. Without even knowing it, she walked in a way that drew men’s eyes.

‘That one’s trouble,’ our kitchen woman Janis would mutter over her pots and pans. As for Niamh herself, she was ever critical.

‘Isn’t it bad enough being half Briton,’ she said crossly, ‘without having to look the part as well? See this?’ She tugged at her thick plait, and the red-gold strands unravelled in a shining curtain. ‘Who would take me for a daughter of Sevenwaters? I could be a Saxon, with this head of hair! Why couldn’t I be tiny and graceful like Mother?’

I studied her for a moment or two, as she began to wield the hairbrush with fierce strokes. For one so displeased with her appearance, she did spend rather a lot of time trying out new hairstyles and changing her gown and ribbons.

‘Are you ashamed to be the daughter of a Briton?’ I asked her.

She glared at me. ‘That’s so like you, Liadan. Always come straight out with it, don’t you? It’s all very well for you, you’re a small copy of Mother yourself, her little right hand. No wonder Father adores you. For you it’s simple.’

I let her words wash over me. She could be like this at times, as if there were too many feelings inside her and they had to burst out somewhere. The words themselves meant nothing. I waited.

Niamh used her hairbrush like an instrument of punishment. ‘Sean, too,’ she said, glaring at herself in the mirror of polished bronze. ‘Did you hear what Father called him? He said, he’s the son Liam never had. What do you think of that? Sean fits in, he knows exactly where he’s going. Heir to Sevenwaters, beloved son with not one but two fathers – he even looks the part. He’ll do all the right things – wed Aisling, which will make everyone happy, be a leader of men, maybe even the one who wins the Islands back for us. His children will follow in his footsteps, and so on, and so on. Brighid save me, it’s so tedious! It’s so predictable.’

‘You can’t have it both ways,’ I said. ‘Either you want to fit in, or you don’t. Besides, we are the daughters of Sevenwaters, like it or not. I’m sure Eamonn will wed you gladly, when it’s time, golden hair or no. I’ve heard no objections from him.’

‘Eamonn? Huh!’ She moved to the centre of the room, where a shaft of light struck gold against the oak boards of the floor, and in this spot she began slowly to turn, so that her white gown and her brilliant shining hair moved around her like a cloud. ‘Don’t you long for something different to happen, something so exciting and new it carries you along with it like a great tide, something that lets your life blaze and burn so the whole world can see it? Something that touches you with joy or with terror, that lifts you out of your safe little path and onto a great wild road whose ending nobody knows? Don’t you ever long for that, Liadan?’ She turned and turned, and she had wrapped her arms around herself as if this were the only way she could contain what she felt.

I sat on the edge of the bed, watching her quietly. After a while I said, ‘You should take care. Such words might tempt the Fair Folk to take a hand in your life. It happens. You know Mother’s story. She was given such a chance, and she took it; and it was only through her courage, and Father’s, that she did not die. To survive their games you must be very strong. For her and for Father the ending was good. But that tale had losers as well. What about her six brothers? Of them, but two remain, or maybe three. What happened damaged them all. And there were others that perished. You would be better to take your life one day at a time. For me, there is enough excitement in helping to deliver a new lamb, or seeing small oaks grow strong in spring rains. In shooting an arrow straight to the mark, or curing a child of the croup. Why ask for more, when what we have is so good?’

Niamh unwrapped her arms and ran a hand through her hair, undoing the work of the brush in an instant. She sighed. ‘You sound so like Father you make me sick sometimes,’ she said, but the tone was affectionate enough. I knew my sister well. I did not let her upset me often.

‘I’ve never understood how he could do it,’ she went on. ‘Give up everything, just like that. His lands, his power, his position, his family. Just give it away. He’ll never be master of Sevenwaters, that’s Liam’s place. His son will inherit, no doubt; but Iubdan, all he’ll be is the Big Man, quietly growing his trees and tending his flocks, and letting the world pass him by. How could a real man choose to let life go like that? He never even went back to Harrowfield.’

I smiled to myself. Was she blind, that she did not see the way it was between them, Sorcha and Iubdan? How could she live here day by day, and see them look at one another, and not understand why he had done what he had done? Besides, without his good husbandry, Sevenwaters would be nothing more than a well-guarded fortress. Under his guidance our lands had prospered. Everyone knew we bred the best cattle and grew the finest barley in all of Ulster. It was my father’s work that enabled my uncle Liam to build his alliances and conduct his campaigns. I didn’t think there was much point explaining this to my sister. If she didn’t know it by now, she never would.

‘He loves her,’ I said. ‘It’s as simple as that. And yet, it’s more. She doesn’t talk about it, but the Fair Folk had a hand in it, all along. And they will again.’

Finally Niamh was paying attention to me. Her beautiful blue eyes narrowed as she faced me. ‘Now you sound like her,’ she said accusingly. ‘About to tell me a story. A learning tale.’

‘I’m not,’ I said. ‘You aren’t in the mood for it. I was just going to say, we are different, you and me and Sean. Because of what the Fair Folk did, our parents met and wed. Because of what happened, the three of us came into being. Perhaps the next part of the tale is ours.’

Niamh shivered as she sat down beside me, smoothing her skirts over her knees.

‘Because we are neither of Britain nor of Erin, but at the same time both,’ she said slowly. ‘You think one of us is the child of the prophecy? The one who will restore the Islands to our people?’

‘I’ve heard it said.’ It was said a lot, in fact, now that Sean was almost a man, and shaping into as good a fighter, and a leader, as his uncle Liam. Besides, the people were ready for some action. The feud over the Islands had simmered since well before my mother’s day, for it was long years since the Britons had seized this most secret of places from our people. Folk’s bitterness was all the more intense now, since we had come so close to regaining what was rightfully ours. For when Sean and I were children, not six years old, our uncle Liam and two of his brothers, aided by Seamus Redbeard, had thrown their forces into a bold campaign that went right to the heart of the disputed territory. They had come close, achingly close. They had touched the soil of Little Island, and made their secret camp there. They had watched the great birds soar and wheel above the Needle, that stark pinnacle lashed by icy winds and ocean spray. They had launched one fierce sea attack on the British encampment on Greater Island, and at the last they had been driven back. In this battle perished two of my mother’s brothers. Cormack was felled by a sword stroke clean to the heart, and died in Liam’s arms. And Diarmid, seeking to avenge his brother’s loss, fought as if possessed and at length was captured by the Britons. Liam’s men found his body, later, floating in the shallows as they launched their small craft and fled, outnumbered, exhausted and heartsick. He had died from drowning, but only after the enemy had had their sport with him. They would not let my mother see his body when they brought him home.

These Britons were my father’s people. But Iubdan had no part in this war. He had sworn, once, that he would not take arms against his own kind, and he was a man of his word. With Sean it was different. My uncle Liam had never married, and my mother said he never would. There had been a girl, once, that he had loved. But the enchantment fell on him and his brothers. Three years is a long time when you are only sixteen. When at last he came back to the shape of a man, his sweetheart was married and already the mother of a son. She had obeyed her father’s wishes, believing Liam dead. So, he would not take a wife. And he needed no son of his own, for he loved his nephew as fiercely as any father could, and brought him up, without knowing it, in his own image. Sean and I were the children of a single birth, he just slightly my elder. But at sixteen he was more than a head taller, close to being a man, strong of shoulder, his body lean and hard. Liam had ensured he was expert in the arts of war. As well, Sean learned how to plan a campaign, how to deliver a fair judgement, how to understand the thinking of ally and enemy alike. Liam commented sometimes on his nephew’s youthful impatience. But Sean was a leader in the making; nobody doubted that.

As for our father, he smiled and let them get on with it. He recognised the weight of the inheritance Sean must one day carry. But he had not relinquished his son. There was time, as well, for the two of them to walk or ride around the fields and byres and barns of the home farms; for Iubdan to teach his son to care for his people and his land as well as to protect them. They spoke long and often, and held each other’s respect. Only I would catch Mother sometimes, looking at Niamh and looking at Sean and looking at me, and I knew what was troubling her. Sooner or later, the Fair Folk would decide it was time. Time to meddle in our lives again, time to pick up the half-finished tapestry and weave a few more twisted patterns into it. Which would they choose? Was one of us the child of the prophecy, who would at last make peace between our people and the Britons of Northwoods, and win back the Islands of mystic caves and sacred trees? Myself, I rather thought not. If you knew the Fair Folk at all, you knew they were devious and subtle. Their games were complex, their choices never obvious. Besides, what about the other part of the prophecy, which people seemed to have conveniently overlooked? Didn’t it say something about bearing the mark of the raven? Nobody knew quite what that meant, but it didn’t seem to fit any of us. Besides, there must have been more than a few misalliances between wandering Britons and Irish women. We could hardly be the only children who bore the blood of both races. This I told myself; and then I would see my mother’s eyes on us, green, fey, watchful, and a shiver of foreboding would run through me. I sensed it was time. Time for things to change again.

That spring we had visitors. Here in the heart of the great forest, the old ways were strong despite the communities of men and women that now spread over our land, their Christian crosses stark symbols of a new faith. From time to time, travellers would bring across the sea tales of great ills done to folk who dared keep the old traditions. There were cruel penalties, even death, for those who left an offering, maybe, for the harvest gods, or thought to weave a simple spell for good fortune or use a potion to bring back a faithless sweetheart. The druids were all slain or banished, over there. The power of the new faith was great. Backed up with a generous purse and with lethal force, how could it fail?

But here at Sevenwaters, here in this corner of Erin, we were a different breed. The holy fathers, when they came, were mostly quiet, scholarly men who debated an issue with open minds, and listened as much as they spoke. Amongst them, a boy could learn to read in Latin and in Irish, and to write a clear hand, and to mix colours and make intricate patterns on parchment or fine vellum. Amongst the sisters, a girl might learn the healing arts, or how to chant like an angel. In their houses of contemplation there was a place for the poor and dispossessed. They were, at heart, good people. But none from our household was destined to join their number. When my grandfather went away and Liam became lord of Sevenwaters, with all the responsibilities that entailed, many strands were drawn together to strengthen our household’s fabric. Liam rallied the families nearby, built a strong fighting force, became the leader our people had needed so badly. My father made our farms prosperous and our fields plentiful as never before. He planted oaks where once had been barren soil. As well, he put new heart into folk who had drawn very close to despair. My mother was a symbol of what could be won by faith and strength; a living reminder of that other world below the surface. Through her they breathed in daily the truth about who they were, and where they came from; the healing message of the spirit realm.

And then there was her brother Conor. As the tale tells, there were six brothers. Liam I have told of, and the two who were next to him in age, who died in the first battle for the Islands. The youngest, Padraic, was a voyager, returning but seldom. Conor was the fourth brother, and he was a druid. Even as the old faith faded and grew dim elsewhere, we witnessed its light glowing ever stronger in our forest. It was as if each feast day, each marking of the passing season with song and ritual put back a little more of the unity our people had almost lost. Each time, we drew one step closer to being ready. Ready again to reclaim what was stolen from us by the Britons, long generations since. The Islands were the heart of our mystery, the cradle of our belief. Prophecy or no prophecy, the people began to believe that Liam would win them back, or if not him, then Sean who would be master of Sevenwaters after him. The day drew closer, and folk were never more aware of it than when the wise ones came out of the forest to mark the turning of the season. So it was at Imbolc, the year Sean and I were sixteen, a year burned deep in my memory. Conor came, and with him a band of men and women, some in white, and some in the plain homespun robes of those still in their training, and they made the ceremony to honour Brighid’s festival, deep in the woods of Sevenwaters.

They came in the afternoon, quietly as usual. Two very old men, and one old woman, walking in plain sandals up the path from the forest. Their hair was knotted into many small braids, woven about with coloured thread. There were young folk wearing the homespun, both boys and girls; and there were men of middle years, of whom my uncle Conor was one. Come late to the learning of the great mysteries, he was now their leader, a pale, grave man of middle height, his long chestnut hair streaked with grey, his eyes deep and serene. He greeted us all with quiet courtesy, my mother, Iubdan, Liam, then the three of us. And our guests, for several households had gathered here for the festivities. Seamus Redbeard, a vigorous old man whose snowy hair belied his name. His new wife, a sweet girl not so much older than myself. Niamh had been shocked to see this match.

‘How can she?’ she whispered to me behind her hand. ‘How can she lie with him? He’s old, so old. And fat. And he’s got a red nose. Look, she’s smiling at him! I’d rather die!’

I glanced at her a little sourly. ‘You’d best take Eamonn, then, and be glad of the offer, if what you want is a beautiful young man,’ I whispered back. ‘You’re unlikely to do better. Besides, he’s wealthy.’

‘Eamonn? Huh!’

This seemed to be the response whenever I made this suggestion. I wondered, not for the first time, what Niamh really did want. There was no way to see inside that girl’s head. Not like Sean and me. Perhaps it was our being twins, or maybe it was something else, but the two of us never had any problem talking without words. It became necessary, even, to set a guard on your own mind at times, so that the other could not read it. It was both a useful skill and an inconvenient one.

I looked at Eamonn, where he stood now with his sister Aisling, greeting Conor and the rest of the robed procession. I could not really see what Niamh’s problem was. Eamonn was the right age, just a year or two older than my sister. He was comely enough; a little serious maybe, but that could be remedied. He was well built, with glossy brown hair and fine dark eyes. He had good teeth. To lie with him would be – well, I had little knowledge of such things, but I imagined it would not be repulsive. And it would be a match well regarded by both families. Eamonn had come very young to his inheritance, a vast domain surrounded by treacherous marshlands, to the east of Seamus Redbeard’s land and curving around close by the pass to the north. Eamonn’s father, who bore the same name, had been killed in rather mysterious circumstances some years back. My uncle Liam and my father did not always agree, but they were united in their refusal to discuss this particular topic. Eamonn’s mother had died when Aisling was born. So Eamonn had grown up with immense wealth and power, and an overabundance of influential advisers: Seamus, who was his grandfather; Liam, who had once been betrothed to his mother; my father, who was somehow tied up in the whole thing. It was perhaps surprising that Eamonn had become very much his own man, and despite his youth kept his own control over his estates and his not inconsiderable private army. That explained, maybe, why he was such a solemn young man. I found that I had been scrutinising him closely, as he finished speaking with one of the younger druids and glanced my way. He gave me a half-smile, as if in defiance of my assessment, and I looked away, feeling a blush rise to my cheeks. Niamh was silly, I thought. She was unlikely to do any better, and at seventeen, she needed to make up her mind quickly, before somebody else did it for her. It would be a very strong partnership, and made stronger still by the tie of kinship with Seamus, who owned the lands between. He who controlled all of that could deal a heavy blow to the Britons, when the time came.