Полная версия

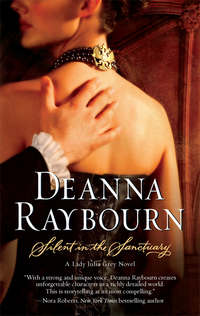

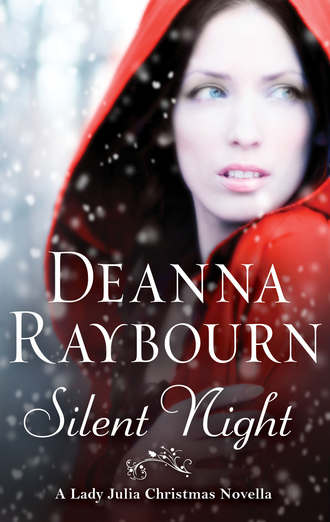

Silent Night: A Lady Julia Christmas Novella

’Tis the season for an investigation! Lady Julia and Nicholas Brisbane return for a Christmas caper at Bellmont Abbey….

After a year of marriage—and numerous adventures—Lady Julia and Brisbane hope for a quiet, intimate Christmas together…until they find themselves at her father’s ancestral estate, Bellmont Abbey, with her eccentric family and a menagerie of animals.

Nevertheless, Julia looks forward to a lively family gathering…but amongst the celebrations, a mystery stirs. There are missing jewels, new faces at the Abbey, and a prowling ghost that brings back unwelcome memories from a previous holiday—one that turned deadly. Is a new culprit recreating crimes of the past? And will Brisbane let Julia investigate…?

Don’t miss a single tale in the Lady Julia series—read the book that started it all, Silent in the Grave, available now.

Silent Night

A Lady Julia Christmas Novella

Deanna Raybourn

A sixth-generation native Texan, Deanna Raybourn graduated from the University of Texas at San Antonio with a double major in English and history and an emphasis on Shakespearean studies. She taught high school English for three years in San Antonio before leaving education to pursue a career as a novelist. Deanna makes her home in Virginia, where she lives with her husband and daughter, and is hard at work on the next installment in the award-winning Lady Julia Grey series.

Other books by Deanna Raybourn

Silent in the Grave

Silent in the Sanctuary

Silent on the Moor

Dark Road to Darjeeling

The Dark Enquiry

The Dead Travel Fast

And coming soon

A Spear of Summer Grass

Contents

The First Chapter

The Second Chapter

The Third Chapter

The Fourth Chapter

The Fifth Chapter

The Sixth Chapter

The Seventh Chapter

The Eighth Chapter

The Ninth Chapter

The Tenth Chapter

End Notes

Meeting the Marches

Recipe for March Wassail

Aunt Hermia’s Recipe for Winter Potpourri

The First Chapter

Here we come a-wassailing

Among the leaves so green,

Here we come a-wandering,

So fair to be seen.

“Here We Come A-Wassailing” Traditional English Carol

London December 1, 1889

I tore open the letter and scanned it quickly before brandishing it at my husband. “We are going to Rome,” I informed him. I gave him the letter to read, fairly hopping from foot to foot as he came to the end.

“Bloody hell.”

“We must go,” I insisted.

“We must not,” was Brisbane’s equally firm reply. I smiled to myself, certain I would win this particular skirmish. I was already half-packed in my mind. Rome would be chilly for Christmas, but not so cold as to preclude a full appreciation of the city and all its attendant delights. Parties and entertainments, pageants and festivals—and a new mystery to be solved, given the contents of the letter.

The process of persuading Brisbane to permit me to help him in his investigations as a private enquiry agent was slow. Glacial, in fact. But progress had been made, and through our various adventures we had drawn closer than ever. The anticipation of sharing a new case with him in one of my favourite cities was almost more than I could bear.

My brother, Plum, the newest addition to Brisbane’s staff, held out his teacup. “Any hope of more tea? And another muffin?”

I obliged him, as much for the chance to plan my persuasions as to be sisterly. Besides, Plum had only recently been released from the splints that had held his injured arm in place after a particularly nasty incident of my own making. 1 I still felt a trifle guilty about that. I poured his tea and toasted up a muffin and when I handed them over, he fixed me with a mischievous eye.

“Haven’t you forgot something?”

I cast around in my mind. “Nothing of importance. The significant cases have all been attended to, and the rest are trifling matters Brisbane can either finish himself or hand over to the very excellent Monk. We can be in Rome by the middle of the month.”

Brisbane said nothing. He merely steepled his hands under his chin and regarded me thoughtfully. Plum settled back into his chair, clearly enjoying himself.

“You have forgot.”

I puffed out a little sigh of impatience. “Don’t be cryptic, Plum. You haven’t the cheekbones for it. What is it that I have forgot?”

“Father.”

I smoothed my skirts. “I haven’t forgot Father at all. He knows not all of his children can come home every holiday and he never fusses about Christmas.” That was not entirely true. Father, or to give him his proper title, the Earl March, was a bit of a despot about his children even though there were ten of us and the eldest was past forty. Father liked to play the patriarch and gather us into the fold whenever he could. “It’s been years since the whole clan was gathered at Bellmont Abbey.”

“Ten, to be precise.” The words were clipped and weighty as stones.

I went quite still. “No.”

Plum’s handsome mouth curved into a smile. “Oh, yes. It’s slipped your mind, dearest, but the year is 1889—and that means Twelfth Night falls in 1890.”

I buried my face in my hands. “No.”

Brisbane stirred himself. “What is the significance of 1890?”

I peeped over my fingertips. “The Twelfth Night mummers’ play. Every year the villagers put on a traditional mummers’ play.”

Brisbane groaned. “Not one of those absurdities with St. George and the dragon?”

“The very same.”

I exchanged glances with Plum. His smile sharpened as he picked up the story. “I am sure Julia told you Shakespeare once stayed as a guest of the Marches at Bellmont Abbey. There was apparently a quarrel that ended with the earl’s wife throwing Shakespeare’s only copy of the play he was writing into the fire. They patched things up, and—”

“And to demonstrate he bore no ill will, Shakespeare himself wrote our mummers’ play,” I finished. “Once every decade, instead of the villagers of Blessingstoke performing the traditional play, the family perform the Shakespearean version for the local folk.”

“Every ten years,” Brisbane said, his black brows arched thoughtfully.

“Yes. The men in the family act out the parts and the women are a sort of chorus, robed in white and singing in the background.”

“It is great fun, really,” Plum put in. “Father always plays the king who sends St. George to kill the dragon and the rest of the parts always seem to go to the same people. Except for St. George. That one always falls to the newest male to marry into the family.”

I busied myself with tearing a muffin to bits while Plum’s words registered with Brisbane.

“Absolutely not.”

I turned to him. “But dearest, it is tradition.”

“I am not an enthusiast of tradition.”

He gave me a dangerously pleasant smile as Plum rose to his feet. “I almost wish I could stay for the rest of what promises to be a very lively discussion, but I am afraid I must be off. I shall tell Father to expect you for Christmas then, shall I?”

I threw a shoe at him but he ducked through the door just in time. I went and sat on Brisbane’s desk. “It does not matter what you say or what you do, the answer is still no,” he said evenly.

I slid off the desk and onto his lap. What I said and what I did after that had no bearing on the situation at all except that by the time the housekeeper came to fetch the tea things, our clothes were tidied and the matter had been settled. I would write to my friend in Rome and postpone our arrival until later in January. We were going to Father’s for Christmas and Brisbane would play the part of St. George in the Twelfth Night revels. I tried very hard not to gloat.

The Second Chapter

God rest ye merry, gentlemen

Let nothing you dismay.

“God Rest Ye Merry, Gentlemen” Traditional English Carol

“I am not carrying that cat on my lap all the way to Sussex,” Brisbane informed me. He eyed the basket on the train platform with distaste. I could not entirely blame him. The animal in question, a somewhat pernickety Siamese, belonged to a business associate of Brisbane’s who had remarked upon the cat’s unusual affection for me.

“What else was I to do? Sir Morgan was quite desperate for someone to care for her whilst he is away. He said she pines,” I informed him over the shrieks coming from the basket between us. I rummaged in my reticule for a handkerchief and handed it over. “Here. You’ll want to wipe your cheek. I’m afraid the blood is still oozing a bit.”

I busied myself murmuring soothing words to Nin while Brisbane staunched the flow from the worst of the scratches. To my astonishment, when I straightened, I realized his shoulders were shaking with laughter.

“It is absurd,” he said, looking around us.

“The other travellers do seem to have given us a wide berth,” I admitted.

“Can you blame them?” He surveyed our possessions, and I found myself smiling as well.

“Not precisely a partridge in a pear tree...”

“But we have a raven in a cage, a lurcher on a lead, a Siamese in a basket, and a dormouse in your décolletage. We are a travelling circus.”

“It could be worse,” I reminded him. “At least Portia has taken that wretched Italian greyhound off our hands.” His eyes held mine for a long moment, and I felt a peculiar quiver in my knees. Odd that he could still have so potent an effect upon me after a year and a half of marriage, but Brisbane was not like other husbands. I was reflecting on precisely how he differed when I smelled something foul.

“For God’s sake, Julia, don’t stand about in public mooning over your husband. It isn’t seemly.”

I whirled to find my sister Portia descending upon us with the greyhound in question and a pug of prodigious and possibly Biblical antiquity.

“That dog is getting worse,” I told her. “I am beginning to suspect he sailed with Noah in the ark. Behold, Mr. Pugglesworth, the Original Pug.”

She stooped to kiss my cheek. “Don’t be hateful, Julia, just because you are travelling with a menagerie that would suit Barnum. Hello, Brisbane, how is my favourite brother-in-law?”

He returned her kiss, giving Puggy a wide berth. “Passing well.”

Portia glanced about. “Where is our dear Plum?”

“Finishing up an investigation with Monk,” I informed her. Brisbane’s assistant had agreed to remain in London to attend to any last-minute affairs that might arise. “He will be down tomorrow.”Portia gave Brisbane a bright-eyed look. “I hear you’re to be St. George this year in the revels. How on earth did Julia manage to convince you of that?”

“Your sister can be quite persuasive when she puts her mind to it.”

Portia let out a snort of laughter. “I’ve no doubt. But I’m very pleased you let her persuade you. I want everyone on hand for Jane the Younger’s first Christmas, particularly her godparents.” She turned just as the nanny approached pushing a stately pram. Jane the Younger sat bolt upright, howling with rage.

“Such a passionate child,” I said faintly.

Portia fixed me with a firm look. “She is having a bit of trouble with her teeth.”

“Do they not make a tonic for that? Or a sedative?”

“I am not dosing her with one of those foul patent medicines, Julia. She will be perfectly well in due course. I think.” Jane the Younger was Portia’s first foray into motherhood. The orphaned daughter of Portia’s life companion, Jane was not blood kin to us but she was dear nonetheless. 2 And a good deal dearer when she was clean and quiet and dry, which was not very often.

Portia plucked her from the pram and shoved her into my arms. “Say hello to Auntie Julia, darling.”

Jane the Younger stopped howling long enough to lunge for my earring.

“Such good taste,” I murmured, prying at the chubby little fist.

“Yes, she has developed a penchant for things that sparkle,” Portia said, applying herself to her daughter’s miserly clutch. “Darling, you must let go of Auntie Julia’s ear. No, stop twisting it, my pet. Auntie Julia is starting to cry. Julia, stop being so melodramatic. It is just an earring.”

“It isn’t the earring,” I corrected tautly. “It’s the lobe.”

Jane the Younger released me sharply and opened her mouth to voice her feelings at being denied the pretty trinket as I rubbed at my tender ear. Portia rummaged in her pocket and found the mother-of-pearl teething ring I had bought for the child in the vain hope of purchasing a few moments’ silence.

“Perhaps we ought to board,” Brisbane suggested, his voice almost inaudible above Jane the Younger’s roars.

* * *

In an excess of holiday generosity one year, my father had gifted me with the tiny dower house on his estate. He had meant it as an independence for me, a small bit of property to call my own for the duration of my life, and a lovely property it was. I had decorated the place, lavishing care and attention and great expense upon it—and spent only a handful of nights there since. I was very much looking forward to snuggling down with my husband into the peace and quiet of our own home, a bolthole to which we could withdraw when my family’s boisterous spirits grew too high. I had already sent our butler, Aquinas, and my maid, Morag, down by the earliest train to remove the dust sheets and light the fires. I had ordered a simple supper of Brisbane’s favourites along with a hamper of the best wines from his cellar. Everything would be absolutely perfect for our winter idyll.

I sighed happily and settled my hand into the crook of Brisbane’s arm as the carriage swung onto the long drive leading to the Abbey. Father’s gardener, Whittle, stood just inside the gates with one of his under-gardeners, Wee Ned—a stooped, elderly man who was fondling a bit of topiary. They raised their caps as we passed, and I waved before turning to Brisbane.

“I am so happy we will finally be able to spend time here together, just the two of us,” I added with a meaningful glance at my sister. She put her tongue out at me, an action that Jane the Younger immediately copied.

“Julia! Look what you have taught her! She looks like a common ape.”

I opened my mouth to remonstrate, but the chimneys of the Rookery were just visible above the treetops. Nothing would induce me to quarrel with my sister when bliss was so shortly at hand.

Brisbane gave a slow smile and I remembered the very excellent bed I had ordered installed. Brisbane was most particular about the sturdiness of our beds, and with good reason, I reflected with a pleasant sigh of anticipation.

“I shall send word to Father that we will not be up to dinner tonight,” I whispered.

Before he could reply, Portia gasped. Jane the Younger, startled, shrieked in response, and I turned to where Portia was pointing.

In a little clearing of trees, nestled in a shrubbery of ancient roses, stood the Rookery. Or what was left of it.

The outer walls were still intact, but where the roof should have been there was nothing but rubble. The remains of an enormous oak listed drunkenly against the crumbling south wall, the ground beneath it gaping and wounded where it had torn free.

“My house!” I wailed.

Brisbane’s face was grim. “It looks as though we shall be spending Christmas with your family after all.”

The raven stirred in his cage, fluffing his deep, oil-black feathers and saying in an ominous voice, “Tragedy and woe.”

And from the depths of the basket on my lap, Nin the Siamese began to howl.

The Third Chapter

Call up the butler of this house,

Put on his golden ring;

Let him bring us up a glass of beer,

And better we shall sing.

“Here We Come A-Wassailing” Traditional English Carol

Settling into the Abbey was only marginally less demanding than the Peninsular Campaign. The staff turned out to greet us and it took every last one of them to shift the bags and boxes and cages and baskets from our carriage and the baggage wagon into the Abbey. Built by Cistercians, it was austerely beautiful and enviably spacious as long as one did not mind the occasional ghost. Portia and her assorted pets—she had brought not only Puggy but his greyhound wife, Florence, and an assortment of their ill-begotten pups—took her old room off the picture gallery while Jane the Younger and her nanny were whisked away to the nursery floor. Brisbane and I and our menagerie were given the Jubilee Tower chamber, a rather gorgeous room he had occupied during his only previous stay. It was situated just over the chapel and connected to the old belfry via the bachelors’ wing.

Brisbane looked around as the door closed behind us.

“At least it is removed from the rest of the place,” I soothed. “We shall have some privacy.”

“And hopefully rather fewer dead bodies than last time.” If he was feeling a trifle waspish, I could not blame him. I had promised him a peaceful retreat to the Rookery and instead we would spend the next fortnight nestled rather too firmly in the bosom of my tempestuous family.

Just then the door opened and my maid, Morag, entered. “It’s about time you’ve come. I take you’ve seen the Rookery? His lordship says it weren’t even a very strong wind brought that oak down last night. It were rotted through and through.” Since Morag is never happier than when disaster strikes, she was smiling.

“I saw. I presume you and Aquinas have both been given lodgings here for the duration?”

“Aye. And Mr. Aquinas has been given the task of butlering for the Abbey as Mr. Hoots is having a funny turn.”

“Hoots is unwell?” That was not entirely unusual. Hoots had always been prone to dramatic ailments, usually coinciding neatly with extra work.

“His mind’s slipped a cog. Claiming to be Napoleon, he is. Locked himself belowstairs with a bottle of the earl’s best Armagnac. Won’t come out until Wellington surrenders, he says, and that leaves Mr. Aquinas to do all the organizing of the household.”

I sat down and put my fingertips to my temples, rubbing hard. “We have one fallen tree, one destroyed Rookery, one delusional butler and no good brandy. Is that what you are telling me?”

“And the cook’s down with piles and more than half the staff are suffering from catarrh,” she added maliciously.

I looked to Brisbane, who was smiling broadly. “God bless us, everyone,” he said, spreading his arms wide.

* * *

The situation was rather worse than Morag had described. Hoots had taken not just a bottle of Armagnac but all the decent liquor and locked it up in his room along with the keys to the silver, the wine cellar and the pantry. The cook was indeed down with piles, but the rest of the staff had succumbed to a rather virulent cold that left them wheezing and hacking in various corners of the house. A few had taken to their beds but the rest dragged about, sniffling moistly into unspeakably sodden handkerchiefs. Father had given Aquinas carte blanche to manage the house until Hoots came around. No one had yet wrested the keys from Hoots, so dinner the first night consisted of bottles of beer from the village pub and bread toasted over the drawing room fire. Portia took hers to the nursery to eat with Jane the Younger while the rest of us made an impromptu party around the fireplace in the vast great hall.

Impromptu and awkward. Father, sunk in a sort of black gloom, said scarcely a dozen words, and Aunt Hermia—Father’s younger sister and the nearest thing we children had to a mother—struggled to fill the silences. I noticed none of the usual decorations had been hung, and I wondered if Father’s grim mood was a result of the fact that so few of us would be present for Christmas. No matter, I decided. He would come round as soon as everyone gathered for Twelfth Night.

I smiled at the footman who came to poke up the fire. A local lad, he had been with the family a number of years and, like all the footmen at Bellmont, was called William regardless of his real name. This one was William IV.

“Hello, William.” He gave me a courteous bow but did not smile.

“Is everything well with you and your family?”

“Yes, my lady. Thank you for asking.”

He withdrew at once and I turned to Aunt Hermia. “What ails William? He has always been such a pleasant, chatty fellow.”

She shrugged. “Heaven help me if I know.”

“He isn’t holding a grudge about what happened the last time is he?” I ventured. “I mean, we did apologise about him being poisoned.” 3

“He might still have died,” Father countered, levelling an accusatory gaze at Brisbane. “I seem to remember someone having to force the poor boy to regurgi—”

“That is quite enough, Hector. And you’ve got it very wrong,” Aunt Hermia cut in sharply before Father could continue. “The other victims required Brisbane’s interventions. William slept it off. He woke with nothing more significant than a towering headache.” She turned back to me. “He has been out of sorts for days now, as have most of the staff. So many are out with illness, the rest have worked doubly hard to carry on. We cannot seem to find replacements in Blessingstoke.” She broke off suddenly, darting a quick glance to my father.

Brisbane noted it. He turned to Aunt Hermia. “You are having troubles with the locals? But you have always hired in from the village.”

“Never again,” Father thundered. “I will not have a pack of cowardly, pudding-hearted—”

Aunt Hermia raised a hand. “That will do, Hector.” She spoke to Brisbane. “But he is not wrong. In the last few days, it has become impossible to entice them to work at the Abbey.”

“What reason do they give?” Brisbane enquired. I smiled to myself. He regularly worked on behalf of her Majesty’s government in essential and secretive ways, and yet he could take a healthy interest in domestic dramas.

“They say the place is haunted!” Father’s expression was disgusted.

“It has always been haunted,” I protested. “Everyone knows that.”

“That is precisely the point,” he returned. “We have always had our share of ghosts and they’ve always worked here in spite of it.”

“What has changed?” Brisbane asked, his black gaze thoughtful as it rested on the contents of his glass.

“There has been a fresh sighting inside the Abbey,” Aunt Hermia replied. “When the staff fell ill, I brought in a few new maids from the village. One of them saw a ghost on the servants’ stair and ran screaming home in the middle of the night. She has the busiest tongue in the village. They cannot help they are superstitious, Hector,” she added. “They haven’t the benefit of our education.”

He snorted by way of reply. Brisbane said nothing, and I knew we were both thinking of our previous investigation at the Abbey. A ghost had figured prominently in that adventure.

Father turned abruptly to Brisbane. “I suppose you are still capering about in the private enquiry business?”

Before Brisbane could reply, Aunt Hermia jumped up and took a crystal dish from the mantel. “Brisbane, you must try these sweetmeats. The stillroom maid and I concocted them, and I would know if I had too heavy a hand with the rosewater.”