Полная версия

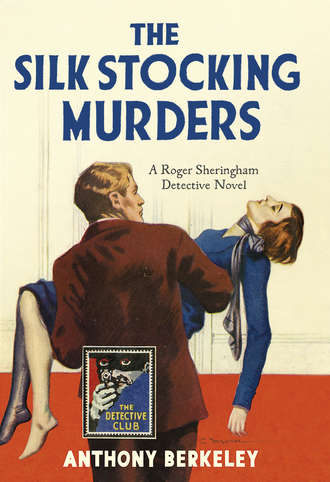

The Silk Stocking Murders

‘THE DETECTIVE STORY CLUB is a clearing house for the best detective and mystery stories chosen for you by a select committee of experts. Only the most ingenious crime stories will be published under the THE DETECTIVE STORY CLUB imprint. A special distinguishing stamp appears on the wrapper and title page of every THE DETECTIVE STORY CLUB book—the Man with the Gun. Always look for the Man with the Gun when buying a Crime book.’

Wm. Collins Sons & Co. Ltd., 1929

Now the Man with the Gun is back in this series of Collins Crime Club reprints, and with him the chance to experience the classic books that influenced the Golden Age of crime fiction.

Copyright

Published by COLLINS CRIME CLUB

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by The Crime Club by W. Collins Sons & Co. Ltd 1923

Copyright © Estate of Anthony Berkeley 1928

Introduction © Tony Medawar 2017

Cover design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 1928, 2017

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008216399

Ebook Edition © February 2017 ISBN: 9780008216405

Version: 2016-12-28

Dedication

TO

A. B. COX

WHO

VERY KINDLY

WROTE THIS BOOK FOR ME

IN HIS SPARE TIME

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Introduction

I. A LETTER FOR MR SHERINGHAM

II. MR SHERINGHAM WONDERS

III. MISS CARRUTHERS IS DRAMATIC

IV. TWO DEATHS AND A JOURNEY

V. ENTER CHIEF-INSPECTOR MORESBY

VI. DETECTIVE SHERINGHAM, OF SCOTLAND YARD

VII. GETTING TO GRIPS WITH THE CASE

VIII. A VISITOR TO SCOTLAND YARD

IX. NOTES AND QUERIES

X. LUNCH FOR TWO

XI. AN INTERVIEW AND A MURDER

XII. SCOTLAND YARD AT WORK

XIII. A VERY DIFFICULT CASE

XIV. DETECTIVE SHERINGHAM SHINES

XV. MR SHERINGHAM DIVERGES

XVI. ANNE INTERVENES

XVII. AN UNOFFICIAL COMBINATION

XVIII. ‘AN ARREST IS IMMINENT’

XIX. MR SHERINGHAM IS BUSY

XX. ALARMS AND EXCURSIONS

XXI. ANNE HAS A THEORY

XXII. THE LAST VICTIM

XXIII. THE TRAP IS SET

XXIV. THE TRAP IS SPRUNG

XXV. ROUND THE GOOD XXXX

The Detective Story Club

About the Publisher

INTRODUCTION

ANTHONY BERKELEY COX (1893–1971) was a versatile author who wrote under several names. Under his real name, he wrote humorous novels, political commentary and even a comic opera. As A. Monmouth Platts, he wrote a light-hearted thriller involving a vanishing debutante. As Francis Iles, he wrote the groundbreaking psychological crime novels Malice Aforethought (1931) and Before the Fact (1932). And, as Anthony Berkeley, he wrote 14 classic detective stories, many of which feature Roger Sheringham, an amateur investigator who works sometimes with—and sometimes against—Chief Inspector Moresby of Scotland Yard.

In some senses, Anthony Berkeley was Roger Sheringham; at the very least the two have much in common. Roger, like his creator, was the son of a doctor and ‘born in a small English provincial town’. Both went to public school and then to Oxford, where Berkeley achieved a Third in Classics and Roger a Second in Classics and History. Both served in the First World War: Berkeley was invalided out of the army with his health permanently impaired, while Roger was ‘wounded twice, not very seriously’. Roger became a bestseller with his first novel, as did Berkeley, and both men spoke disparagingly of their own fiction while being intolerant of others’ criticism. Against this background, Berkeley’s comment that Sheringham was ‘founded on an offensive person I once knew’ is likely to have been an example of the writer’s often-noted peculiar sense of humour.

Humour, and above all ingenuity, are the hallmark of Berkeley’s crime fiction. While many of his contemporaries concentrated on finding ever more improbable means of dispatching victims and ever more implausible means of establishing an alibi, Berkeley focused on turning established conventions of the crime and mystery genre upside down. Thus the explanation of the locked room in Berkeley’s first Sheringham mystery, The Layton Court Mystery (1925), is absurdly straightforward. In another novel, the official detective is right while the amateur sleuth is wrong. In another, the last person known to have seen the victim alive is, after all, the murderer. Above all, facts uncovered by any of Berkeley’s detectives are almost always capable of more than one explanation and the first deductions they draw are rarely entirely correct. In this respect, Berkeley clearly took some of his inspiration from certain historical crimes, particularly those whose solution has never been clear-cut and where the facts, such as there are, routinely offer more than one possible explanation. The Silk Stocking Murders (1928) is one such title, inspired by the murder in 1925 of a young woman in London by a one-legged man; The Wychford Poisoning Case, which has also been reissued in this Detective Club series, is another.

In all, Roger Sheringham appears in ten novel-length mysteries—one of which Berkeley dedicated to himself—and Sheringham is also mentioned in passing in two other novels, The Piccadilly Murder (1929) and Trial and Error (1937). Perhaps the best-known of the Sheringham novels is The Poisoned Chocolates Case (1929) which, again, is based on a real-life crime. This was the attempt in November 1922 by a disgruntled horticulturist to murder the Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police Service, Brigadier-General Sir William Horwood, by sending him a package of Walnut Whips, laced with either arsenic or strychnine. The poisoning with which Cox’s novel is concerned is investigated not only by the police but by Sheringham and the other members of ‘The Crimes Circle’, a private dining club of criminologists. Each member of the Circle advances a plausible explanation of the poisoning but one by one the solutions fall, including—to the reader’s surprise—the solution proposed by Sheringham. Eventually the mystery is solved by Ambrose Chitterwick, an unassuming and aspergic amateur sleuth whose hobbies include philately and horticulture—tweaking the nose of anyone who remembered that it was a horticulturist who made the attempt to poison Sir William Horwood. As well as being a superb puzzle, with multiple solutions, The Poisoned Chocolates Case is fascinating for the links between the fictional ‘Crimes Circle’ and the Detection Club, which Berkeley had founded as a dining club for crime writers in 1929—the same year that The Poisoned Chocolates Case was published. The Detection Club, at least initially, comprised ‘authors of detective stories which rely more upon genuine detective merit than upon melodramatic thrills’, though that definition has been significantly stretched more than once over the nearly 90 years of the Club’s existence. Over the years, Cox would collaborate with members of the Detection Club on various fundraising ventures, including four round-robin mysteries beginning with The Floating Admiral (1931), whose entertaining sequel—The Sinking Admiral—was published by Collins Crime Club in 2016. And in 2016, playing Berkeley in a posthumous game of detective chess, Martin Edwards, the current President of the Detection Club, proposed a wholly plausible additional solution to the Poisoned Chocolates mystery in a British Library reprint.

But Berkeley eventually tired of playing games with detective stories and, though Sheringham would go on to appear in a few recently discovered wartime propaganda pieces, some shorter fiction and even a radio play, the last novel in which he appeared was published in 1934, less than ten years after his debut in The Layton Court Mystery. But Berkeley did not abandon crime fiction altogether. On the contrary, he decided to take crime fiction in what was then a radically new direction. For this new approach, Berkeley decided to use the name of one of his mother’s ancestors, a smuggler called Francis Iles. And, for three years, the real identity of Francis Iles was kept a secret. With Malice Aforethought, the first Iles novel, Berkeley broke the mould. At a stroke, he broadened the range—and respectability—of crime and detective fiction. Though the novel in part derives from an early short story and, while it could also be regarded as a variant of the inverted mystery popularised by Richard Austin Freeman’s Dr Thorndyke stories, Malice Aforethought is a much more complex proposition. For the first time Berkeley achieved what he had tried to do many times before: he focused on psychology. In Malice Aforethought it is the psychology of the murderer; and in the second Iles title, Before the Fact, it is the psychology of the victim. Characteristically, both are based on real-life crimes.

In all, three novels were published as by Francis Iles, with the third—As for the Woman (1939)—less successful than it might have been had it been presented as non-genre fiction, perhaps under yet another pseudonym. While a fourth ‘Francis Iles’ title was planned and even announced, Berkeley had published his last novel.

A few short stories appeared from time to time and, in the late 1950s, he completed two volumes of limericks, which were published under his own name. Berkeley also wrote some radio plays for the BBC, including one that, though credited to Anthony Berkeley, included two songs ‘by Anthony B. Cox’—and was introduced on its original broadcast by none other than Francis Iles!

In all, Anthony Berkeley published 24 books in a little over 14 years. He was also a prolific contributor to periodicals under his various names, authoring over 300 stories, sketches and articles; and he also reviewed crime fiction and other books up until shortly before his death in 1971.

To Agatha Christie, Berkeley was ‘Detection and crime at its wittiest—all his stories are amusing, intriguing and he is a master of the final twist, the surprise denouement.’ Dorothy L. Sayers also admired Berkeley and has Harriet Vane, in the Lord Peter Wimsey novel Have His Carcase (1932), describe the ‘twistiness’ of what she calls the Roger Sheringham method—‘You prove elaborately and in detail that A did the murder; then you give the story one final shake, twist it round a fresh corner, and find that the real murderer is B.’ The last word can be left to the mystery novelist Christianna Brand, a friend and near neighbour of Berkeley’s in London, who when reminiscing about the early years of the Detection Club commented: ‘Sometimes I have thought he was really the cleverest of all of us.’

TONY MEDAWAR

September 2016

CHAPTER I

A LETTER FOR MR SHERINGHAM

ROGER SHERINGHAM halted before the little box just inside the entrance of The Daily Courier’s enormous building behind Fleet Street. Its occupant, alert for unauthorised intruders endeavouring to slip past him, nodded kindly.

‘Only one for you this morning, sir,’ he said, and produced a letter.

With another nod, which he strove to make as condescending as the porter’s (and failed), Roger passed into the lift and was hoisted smoothly into the upper regions. The letter in his hand, he made his way through mazy, stone-floored passages into the dark little room set apart for his own use. Roger Sheringham, whose real business in life was that of a best-selling novelist, had stipulated when he consented to join The Daily Courier as criminological expert and purveyor of chattily-written articles on murder, upon a room of his own. He only used it twice a week, but he had carried his point. That is what comes of being a personal friend of an editor.

Bestowing his consciously dilapidated hat in a corner, he threw his newspaper on the desk and slit open the letter.

Roger always enjoyed this twice-weekly moment. In spite of his long acquaintance with them, ranging over nearly ten years, he was still able to experience a faint thrill on receiving letters from complete strangers. Praise of his work arriving out of the unknown delighted him; abuse filled him with combative joy. He always answered each one with individual care. It would have warmed the hearts of those of his correspondents who prefaced their letters with diffident apologies for addressing him (and nine out of ten of them did so), to see the welcome their efforts received. All authors are like this—and all authors are careful to tell their friends what a nuisance it is having to waste so much time in answering the letters of strangers, and how they wish people wouldn’t do it. All authors, in fact, are—But that is enough about authors.

It goes without saying that since he had joined The Daily Courier Roger’s weekly bag of strangers had increased very considerably. It was therefore not without a certain disappointment that he had received this solitary specimen from the porter’s hands this morning. A little resentful, he drew it from its envelope. As he read, his resentment disappeared. A little pucker appeared between his eyebrows. The letter was an unusual one, decidedly.

It ran as follows:

The Vicarage,

Little Mitcham, Dorset.

DEAR SIR,—You will, I hope, pardon my presumption in writing to you at all, but I trust that you will accept the excuse that my need is urgent. I have read your very interesting articles in The Daily Courier and, studying them between the lines, feel that you are a man who will not resent my present action, even though it may transfer a measure of responsibility to you which might seem irksome. I would have come up to London to see you in person, but that the expense of such a journey is, to one in my position, almost prohibitive.

Briefly, then, I am a widower, of eight years’ standing, with five daughters. The eldest, Anne, has taken upon her shoulders the duties of my dear wife, who died when Anne was sixteen; and she was, till ten months ago, ably seconded by the sister next to her in age, Janet. I need hardly explain to you that, on the stipend of a country parson, it has not been an easy task to feed, clothe and educate five growing girls. Janet, therefore, who, I may add, has always been considered the beauty of the family, decided ten months ago to seek her fortune elsewhere. We did our best to dissuade her, but she is a high-spirited girl and, having made up her mind, refused to alter it. She also pointed out that not only would there be one less mouth to feed, but, should she be able to obtain employment of even a moderately lucrative nature, she would be able to make a modest, but undoubtedly helpful, contribution towards the household expenses.

Janet did carry out her intention and left us, going, presumably, to London. I write ‘presumably’ because she refused most firmly to give us her address, saying that not until she was securely established in her new life, whatever that should be, would she allow us even to communicate with her, in case we might persuade her, in the event of her not meeting with initial success, to give up and come home again. She did however write to us occasionally herself, and the postmark was always London, though the postal district varied with almost every letter. From these letters we gathered that, though remaining confident and cheerful, she had not yet succeeded in obtaining a post of the kind she desired. She had, however, she told us, found employment sufficiently remunerative to allow her to keep herself in comparative comfort, though she never mentioned the precise nature of the work in which she was engaged.

She had been in the habit of writing to us about once a week or so, but six weeks ago her letters ceased and we have not heard a word from her since. It may be that there is no cause for alarm, but alarm I do feel nevertheless. Janet is an affectionate girl and a good daughter, and I cannot believe that, knowing the distress it would cause us, she would willingly have omitted to let us hear from her in this way. I cannot help feeling that either her letters have been going astray or else the poor girl has met with an accident of some sort.

My reasons, sir, for troubling you with all this are as follows. I am perhaps an old-fashioned man, but I do not care to approach the police in the matter and have Janet traced when probably there is no more the matter than an old man’s foolish fancies; and I am quite sure that, assuming these fancies to have no foundation, Janet would much resent the police poking their noses into her affairs. On the other hand, if there has been an accident, the fact is almost certain to be known at the offices of a paper such as The Daily Courier. I have therefore determined, after considerable reflection, to trespass upon your kindness, on which of course I have no claim at all, to the extent of asking you to make discreet enquiries of such of your colleagues as might be expected to know, and acquaint me with the result. In this way recourse to the police may still be avoided, and news given me of my poor girl without unpleasant publicity or officialism.

If you prefer to have nothing to do with my request, I beg of you to let me know and I will put the matter to the police at once. If, on the other hand, you are so kind as to humour an old man, any words of gratitude on my part become almost superfluous.—Yours truly,

A. E. MANNERS.

P.S.—I enclose a snapshot of Janet taken two years ago, the only one we have.

‘The poor old bird!’ Roger commented mentally, as he reached the end of this lengthy letter, written in a small, crabbed handwriting which was not too easy to decipher. ‘But I wonder whether he realises that there are about eight thousand accidents in the streets of London every twelve months? This is going to be a pretty difficult little job.’ He looked inside the envelope again and drew out the snapshot.

Amateur snapshots have a humorous name, but they are seldom really as bad as reputed. This one was a fair average specimen, and showed four girls sitting on a sea-shore, their ages apparently ranging from ten to something over twenty. Under one of them was written, in the same crabbed handwriting, the word ‘Janet’. Roger studied her. She was pretty, evidently, and in spite of the fact that her face was covered with a very cheerful smile, Roger thought that he could recognise her from the picture should he ever be fortunate enough to find her.

For as to whether he was going to look for her or not, there was no question. It had simply never occurred to Roger that he might, after all, not do so. Roger (whatever else he might be) was a man of quick sympathies, and that stilted letter through whose formal phrases tragedy peeped so plainly, had touched him more than a little. But for the fact that an article had to be written before lunch-time, he would have set about it that very moment, without the least idea of how he was going to prosecute the search.

As it was, however, circumstances prevented him from doing anything in the matter for another ninety minutes, and by that time his brain, working automatically as he wrote, had evolved a plan. He felt fairly certain that the girl was still in London, alive and flourishing, and had postponed writing home as the ties that bound her to Dorsetshire began to weaken; the old man’s anxiety was no doubt ill-founded, but that did not mean that it must not be relieved. Besides, the quest would prove a pretty little exercise for those sleuth-like powers which Roger was so sure he possessed. Nevertheless, unharmed and merely unfilial as he did not doubt the girl to be, it was easier to begin operations from the other end. If she had had an accident she would be considerably easier to trace than if she had not, and by establishing first the negative fact, Roger would be able the sooner to reassure the vicar. And as the only real clue he had was the snapshot, he had better start from that.

Instead, therefore, of betaking himself to Piccadilly Circus in the blithe confidence that Janet Manners, like everybody else in London, would be certain to come along there sooner or later, he ran up two more flights of stairs in the same building, and, the snapshot in his hand, sought out the photographic department of The Daily Courier’s illustrated sister, The Daily Picture.

‘Hullo, Ben,’ he greeted the serious, horn-bespectacled young man who presided over the studio and spent most of his days in photographing mannequins, who left him cold, in garments which left them cold. ‘I suppose you’ve never had a photograph through your hands of this girl, have you? The one marked Janet.’

The bespectacled one scrutinised the snapshot with close attention. Every photograph that appeared in The Daily Picture passed, at one time or another, through his hands, and his memory was prodigious. ‘She does look a bit familiar,’ he admitted.

‘She does, eh?’ Roger cried, suddenly apprehensive. ‘Good man. Rack your brains. I want her placed, badly.’

The other bent over the snapshot again. ‘Can’t you help me?’ he asked. ‘In what connection would I have come across her? Is she an actress, or a mannequin, or a titled beauty, or what?’

‘She’s not a titled beauty, I can tell you that; but she might have been either of the other two. I haven’t the faintest notion what she is.’

‘Why do you want to know if we’ve ever had a photograph of her through here, then?’

‘Oh, it’s just a personal matter,’ Roger said evasively. ‘Her people haven’t heard from her for a week or two and they’re beginning to think she’s been run over by a bus or something like that. You know how fussy the parents of that sort of girl are.’

The other shook his head and handed back the snapshot. ‘No, I’m sorry, but I can’t place her. I’m sure I’ve seen her face before, but you’re too vague. If you could tell me, now, that she had been run over by a bus, or had some other accident, or been something (anything to provide a peg for my memory to hang on) I might have been able to—wait a minute, though!’ He snatched the photograph back and studied it afresh. Roger looked on tensely.

‘I’ve got it!’ the bespectacled one proclaimed in triumph. ‘It was the word “accident” that gave me the clue. Have you ever noticed what a curious thing memory is, Sheringham? Present it with a blank surface, and it simply slides helplessly across it; but give it just the slightest little peg to grip on, and—’