Полная версия

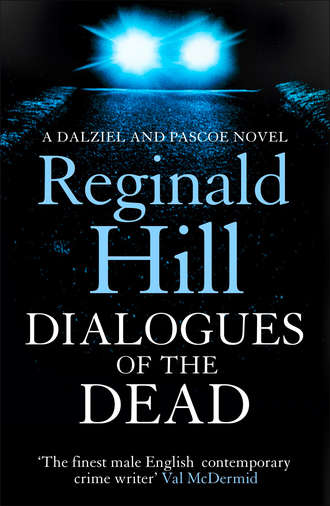

Dialogues of the Dead

The best he could manage by way of demur was, ‘Well, we are rather busy … How many entries are you anticipating?’

‘This sort of thing has a very limited appeal,’ said Follows confidently. ‘I’d be surprised if we get into double figures. Couple of dozen at the very most. You can run through them in your tea break.’

‘That’s a hell of a lot of tea,’ grumbled Rye when the first sackful of scripts was delivered from the Gazette. But Dick Dee had just smiled as he looked at the mountain of paper and said, ‘It’s mute inglorious Milton time, Rye. Let’s start sorting them out.’

The initial sorting out had been fun.

The idea of refusing to read anything not typewritten had seemed very attractive, but rapidly they realized this was too Draconian. On the other hand as more sackloads arrived, they knew they had to have some rules of inadmissibility.

‘Nothing in green ink,’ said Dee.

‘Nothing on less than A5,’ said Rye.

‘Nothing handwritten where the letters aren’t joined up.’

‘Nothing without meaningful punctuation.’

‘Nothing which requires use of a magnifying glass.’

‘Nothing that has organic matter adhering to it,’ said Rye, picking up a sheet which looked as if it had recently lined a cat tray.

Then she’d thought that perhaps the offending stain had come from some baby whose housebound mother was desperately trying to be creative at feeding time, and residual guilt had made her protest strongly when Dick had gone on, ‘And nothing sexually explicit or containing four-letter words.’

He had listened to her liberal arguments with great patience, showing no resentment of her implied accusation that he was at best a frump, at worst a fascist.

When she finished, he said mildly, ‘Rye, I agree with you that there is nothing depraved, disgusting or even distasteful about a good fuck. But as I know beyond doubt that there’s no way any story containing either a description of the act or a derivative of the word is going to get published in the Gazette, it seems to me a useful filter device. Of course, if you want to read every word of every story …’

The arrival of yet another sackful from the Gazette had been a clincher.

A week later, with stories still pouring in and nine days to go before the competition closed, she had become much more dismissive than Dee, spinning scripts across to the dump bin after an opening paragraph, an opening sentence even, or, in some cases, just the title, while he read through nearly all of his and was building a much higher possibles pile.

Now she looked at the script he had interrupted her with and said, ‘First Dialogue? That mean there’s going to be more?’

‘Poetic licence, I expect. Anyway, read it. I’d be interested to hear what you think.’

A new voice interrupted them.

‘Found the new Maupassant yet, Dick?’

Suddenly the light was blocked out as a long lean figure loomed over Rye from behind.

She didn’t need to look up to know this was Charley Penn, one of the reference library’s regulars and the nearest thing Mid-Yorkshire had to a literary lion. He’d written a moderately successful series of what he called historical romances and the critics bodice-rippers, set against the background of revolutionary Europe in the decades leading up to 1848, with a hero loosely based on the German poet Heine. These had been made into a popular TV series where the ripping of bodices was certainly rated higher than either history or even romance. His regular attendance in the reference library had nothing to do with the pursuit of verisimilitude in his fictions. In his cups he had been heard to say of his readers, ‘You can tell the buggers owt. What do they know?’ though in fact he had acquired a wide knowledge of the period in question through the ‘real’ work he’d been researching now for many years, which was a critical edition with metrical translation of Heine’s poems. Rye had been surprised to learn that he was a school contemporary of Dick Dee. The ten years which Dee’s equanimity of temperament erased from his forty-something seemed to have been dumped on Penn, whose hollow cheeks, deep-set eyes and unkempt beard gave him the look of an old Viking who’d ravished and pillaged a raid too far.

‘Probably not,’ said Dee. ‘Be glad of your professional opinion though, Charley.’

Penn moved round the table so that he was looking down at Rye and showed uneven teeth in what she called his smarl, assuming he intended it as a smile and couldn’t help that it came out like a snarl. ‘Not unless you’ve got a sudden budget surplus.’

When it came to professional opinions, or indeed any activity connected with his profession, Charley Penn’s insistence that time equalled money made lawyers seem open-handed.

‘So how can I help you?’ said Dee.

‘Those articles you were tracking down for me, any sign yet?’

Penn had no difficulty squaring his assertion that the labourer was worthy of his hire with using Dee as his unpaid research assistant, but the librarian never complained.

‘I’ll just check to see if there’s anything in today’s post,’ he said.

He rose and went into the office behind the desk.

Penn remained, his gaze fixed on Rye.

She looked back unblinkingly and said, ‘Yes?’

From time to time she’d caught the old Viking looking at her like he was once more feeling the call of the sea, though so far he’d stopped short of rapine and pillage. In fact his preferred model seemed to be that guy in the play (what the hell was his name?) who went around the Forest of Arden, pinning poems to trees. From time to time scraps of Penn’s Heine translations would be put in her way. She’d open a file or pick up a book and there would be a few lines about a despairing lover staring down at himself staring up at his beloved’s window or a lonely northern fir-tree pining for the hand of an unattainably distant palm. Their presence was explained, if explanation were demanded, by inadvertence, accompanied by a knowing version of the smarl which was what she got now as Penn said, ‘Enjoy,’ and went after Dee.

Now Rye gave her full attention to the ‘First Dialogue’, skimming through it rapidly, then reading it again more slowly.

By the time she’d finished, Dee had returned and Penn was back in his usual seat in one of the study alcoves from which he had been known to bellow abuse at young students whose ideas of silence did not accord with his own.

‘What do you think?’ said Dee.

‘Why the hell am I reading this? is what I think,’ said Rye. ‘OK, the writer’s trying to be clever, using a single episode to hint at a whole epic to come, but it doesn’t really work, does it? I mean, what’s it about? Some kind of metaphor of life or what? And what the hell’s that funny illustration all about? I hope you’re not showing me this as the best thing you’ve come across. If so, I don’t want to look at any of the other stuff in your possibles pile.’

He shook his head, smiling. No smarl this. He had a rather nice smile. One of the rather nice things about it was that he used it alike to greet compliment or insult, triumph or disaster. A couple of days earlier for instance a lesser man might have flapped when a badly plugged shelf had collapsed under the weight of the twenty-volume Oxford English Dictionary, scattering a party of civic dignitaries on a tour of the borough’s newly refurbished Heritage, Arts and Library Centre. Only one of the visitors had been hit, receiving the full weight of Volume II on his toe. This was Councillor Cyril Steel, a virulent opponent of the Centre whose voice had frequently been raised in the council against ‘wasting good public money on a load of airy nowt’. Percy Follows had run around like a panicked poodle, fearing a PR disaster, but Dee had merely smiled into the TV camera recording the event for BBC Mid-Yorks and said, ‘Now even Councillor Steel will have to admit that a little learning can be a dangerous thing and not all our nowts are completely airy,’ and continued with his explanatory address.

Now he said, ‘No, I’m not suggesting this as a contender for the prize, though it’s not badly written. As for the drawing, it’s part illustration and part illumination, I think. But what’s really interesting is the way it chimes with something I read in today’s Gazette.’

He picked up a copy of the Mid-Yorkshire Gazette from the newspaper rack. The Gazette came out twice weekly, on Wednesdays and Saturdays. This was the midweek edition. He opened it at the second page, set it before her and indicated a column with his thumb.

AA MAN DIES IN TRAGIC ACCIDENT

The body of Mr Andrew Ainstable (34), a patrol officer with the Automobile Association, was found apparently drowned in a shallow stream running under the Little Bruton road on Tuesday morning. Thomas Killiwick (27), a local farmer who made the discovery, theorized that Mr Ainstable, who it emerged was on his way to a Home Start call at Little Bruton, may have stopped for a call of nature, slipped, and banged his head, but the police are unable to confirm or to deny this theory at this juncture. Mr Ainstable is survived by his wife, Agnes, and a widowed mother. An inquest is expected to be called in the next few days.

‘So what do you think?’ asked Dee again.

‘I think from the style of this report that they were probably wise at the Gazette to ask us to judge the literary merit of these stories,’ said Rye.

‘No. I mean this Dialogue thing. Bit of an odd coincidence, don’t you think?’

‘Not really. I mean, it’s probably not a coincidence at all. Writers must often pick up ideas from what they read in the papers.’

‘But this wasn’t in the Gazette till this morning. And this came out of the bag of entries they sent round last night. So presumably they got it some time yesterday, the same day this poor chap died, and before the writer could have read about it.’

‘OK, so it’s a coincidence after all,’ said Rye irritably. ‘I’ve just read a story about a man who wins the lottery and has a heart attack. I dare say that this week somewhere there’s been a man who won something in the lottery and had a heart attack. It didn’t catch the attention of the Pulitzer Prize mob at the Gazette, but it’s still a coincidence.’

‘All the same,’ said Dee, clearly reluctant to abandon his sense of oddness. ‘Another thing, there’s no pseudonym.’

The rules of entry required that, in the interests of impartial judging, entrants used a pseudonym under their story title. They also wrote these on a sealed envelope containing their real name and address. The envelopes were kept at the Gazette office.

‘So he forgot,’ said Rye. ‘Not that it matters, anyway. It’s not going to win, is it? So who cares who wrote it? Now, can I get on?’

Dick Dee had no argument against this. But Rye noticed he didn’t put the typescript either into the dump bin or on to his possibles pile, but set it aside.

Shaking her head, Rye turned her attention to the next story on her pile. It was called ‘Dreamtime’, written in purple ink in a large spiky hand averaging four words to a line, and it began:

When I woke up this morning I found I’d had a wet dream, and as I lay there trying to recall it, I found myself getting excited again …

With a sigh, she skimmed it over into the dump bin and picked another.

CHAPTER THREE

‘What the fuck are you playing at, Roote?’ snarled Peter Pascoe.

Snarling wasn’t a form of communication that came easily to him, and attempting to keep his upper teeth bared while emitting the plosive P produced a sound effect which was melodramatically Oriental with little of the concomitant sinisterity. He must pay more attention next time his daughter’s pet dog, which didn’t much like men, snarled at him.

Roote pushed the notebook he’d been scribbling in beneath a copy of the Gazette and regarded him with an expression of amiable bewilderment.

‘Sorry, Mr Pascoe? You’ve lost me. I’m not playing at anything and I don’t think I know the rules of the game you’re playing. Do I need a racket too?’

He smiled towards Pascoe’s sports bag from which protruded the shaft of a squash racket.

Cue for another snarl on the line, Don’t get clever with me, Roote!

This was getting like a bad TV script.

As well as snarling he’d been trying to loom menacingly. He had no way of knowing how menacing his looming looked to the casual observer, but it was playing hell with the strained shoulder muscle which had brought his first game of squash in five years to a premature conclusion. Premature? Thirty seconds into foreplay isn’t premature, it is humiliatingly pre-penetrative.

His opponent had been all concern, administering embrocation in the changing room and lubrication in the University Staff Club bar, with no sign whatsoever of snigger. Nevertheless, Pascoe had felt himself sniggered at and when he made his way through the pleasant formal gardens towards the car park and saw Franny Roote smiling at him from a bench, his carefully suppressed irritation had broken through and before he had time to think rationally he was deep into loom and snarl.

Time to rethink his role.

He made himself relax, sat down on the bench, leaned back, winced, and said, ‘OK, Mr Roote. Let’s start again. Would you mind telling me what you’re doing here?’

‘Lunch break,’ said Roote. He held up a brown paper bag and emptied its contents on to the newspaper. ‘Baguette, salad with mayo, low fat. Apple, Granny Smith. Bottle of water, tap.’

That figured. He didn’t look like a man on a high-energy diet. He was thin just this side of emaciation, a condition exacerbated by his black slacks and T-shirt. His face was white as a piece of honed driftwood and his blond hair was cut so short he might as well have been bald.

‘Mr Roote,’ said Pascoe carefully, ‘you live and work in Sheffield which means that even with a very generous lunch break and a very fast car, this would seem an eccentric choice of luncheon venue. Also this is the third, no I think it’s the fourth time I have spotted you in my vicinity over the past week.’

The first time had been a glimpse in the street as he drove home from Mid-Yorkshire Police HQ early one evening. Then a couple of nights later as he and Ellie rose to leave a cinema, he’d noticed Roote sitting half a dozen rows further back. And the previous Sunday as he took his daughter, Rosie, for a stroll in Charter Park to feed the swans, he was sure he’d spotted the black-clad figure standing on the edge of the unused bandstand.

That’s when he’d made a note to ring Sheffield, but he’d been too busy to do it on Monday and by Tuesday it had seemed too trivial to make a fuss over. But now on Wednesday, like a black bird of ill omen, here was the man once more, this time too close for mere coincidence.

‘Oh gosh, yes, I see. In fact I’ve noticed you a couple of times too, and when I saw you coming out of the Staff Club just now, I thought, Good job you’re not paranoiac, Franny boy, else you might think Chief Inspector Pascoe is stalking you.’

This was a reversal to take the breath away.

Also a warning to proceed with great care.

He said, ‘So, coincidence for both of us. Difference is, of course, I live and work here.’

‘Me too,’ said Roote. ‘Don’t mind if I start, do you? Only get an hour.’

He bit deep into the baguette. His teeth were perfectly, almost artistically, regular and had the kind of brilliant whiteness which you expected to see reflecting the flash-bulbs at a Hollywood opening. Prison service dentistry must have come on apace in the past few years.

‘You live and work here?’ said Pascoe. ‘Since when?’

Roote chewed and swallowed.

‘Couple of weeks,’ he said.

‘And why?’

Roote smiled. The teeth again. He’d been a very beautiful boy.

‘Well, I suppose it’s really down to you, Mr Pascoe. Yes, you could say you’re the reason I came back.’

An admission? Even a confession? No, not with Franny Roote, the great controller. Even when you changed the script in mid-scene, you still felt he was still in charge of direction.

‘What’s that mean?’ asked Pascoe.

‘Well, you know, after that little misunderstanding in Sheffield, I lost my job at the hospital. No, please, don’t think I’m blaming you, Mr Pascoe. You were only doing your job, and it was my own choice to slit my wrists. But the hospital people seemed to think it showed I was sick, and of course, sick people are the last people you want in a hospital. Unless they’re on their backs, of course. So soon as I was discharged, I was … discharged.’

‘I’m sorry,’ said Pascoe.

‘No, please, like I say, not your responsibility. In any case, I could have fought it, the staff association were ready to take up the cudgels and all my friends were very supportive. Yes, I’m sure a tribunal would have found in my favour. But it felt like time to move on. I didn’t get religion inside, Mr Pascoe, not in the formal sense, but I certainly came to see that there is a time for all things under the sun and a man is foolish to ignore the signs. So don’t worry yourself.’

He’s offering me absolution! thought Pascoe. One moment I’m snarling and looming, next I’m on my knees being absolved!

He said, ‘That still doesn’t explain …’

‘Why I’m here?’ Roote took another bite, chewed, swallowed. ‘I’m working for the university gardens department. Bit of a change, I know. Very welcome, though. Hospital portering’s a worthwhile job, but you’re inside most of the time, and working with dead people a lot of the time. Now I’m outdoors, and everything’s alive! Even with autumn coming on, there’s still so much of life and growth around. OK, there’s winter to look forward to, but that’s not the end of things, is it? Just a lying dormant, conserving energy, waiting for the signal to re-emerge and blossom again. Bit like prison, if that’s not too fanciful.’

I’m being jerked around here, thought Pascoe. Time to crack the whip.

‘The world’s full of gardens,’ he said coldly. ‘Why this one? Why have you come back to Mid-Yorkshire?’

‘Oh, I’m sorry, I should have said. That’s my other job, my real work – my thesis. You know about my thesis? Revenge and Retribution in English Drama? Of course you do. It was that which helped set you off in the wrong direction, wasn’t it? I can see how it would, with Mrs Pascoe being threatened and all. You got that sorted, did you? I never read anything in the papers.’

He paused and looked enquiringly at Pascoe who said, ‘Yes, we got it sorted. No, there wasn’t much in the papers.’

Because there’d been a security cover-up, but Pascoe wasn’t about to go into that. Irritated though he was by Roote, and deeply suspicious of his motives, he still felt guilty at the memory of what had happened. With Ellie being threatened from an unknown source, he’d cast around for likely suspects. Discovering that Roote, whom he’d put away as an accessory to murder some years ago, was now out and writing a thesis on revenge in Sheffield where he was working as a hospital porter, he’d got South Yorkshire to shake him up a bit then gone down himself to have a friendly word. On arrival, he’d found Roote in the bath with his wrists slashed, and when later he’d had to admit that Roote had no involvement whatsoever in the case he was investigating, the probation service had not been slow to cry harassment.

Well, he’d been able to show he’d gone by the book. Just. But he’d felt then the same mixture of guilt and anger he was feeling now.

Roote was talking again.

‘Anyway, my supervisor at Sheffield got a new post at the university here, just started this term. He’s the one who helped me get fixed up with the gardening job, in fact, so you see how it all slotted in. I could have got a new supervisor, I suppose, but I’ve just got to the most interesting part of my thesis. I mean, the Elizabethans and Jacobeans have been fascinating, of course, but they’ve been so much pawed over by the scholars, it’s difficult to come up with much that’s really new. But now I’m on to the Romantics: Byron, Shelley, Coleridge, even Wordsworth, they all tried their hands at drama you know. But it’s Beddoes that really fascinates me. Do you know his play Death’s Jest-Book?’

‘No,’ said Pascoe. ‘Should I?’

In fact, it came to him as he spoke that he had heard the name Beddoes recently.

‘Depends what you mean by should. Deserves to be better known. It’s fantastic. And as my supervisor’s writing a book on Beddoes and probably knows more about him than any man living, I just had to stick with him. But it’s a long way to travel from Sheffield even with a decent car, and the only thing I’ve been able to afford has more breakdowns than an inner-city teaching staff! It really made sense for me to move too. So everything’s turned out for the best in the best of all possible worlds!’

‘This supervisor,’ said Pascoe, ‘what’s his name?’

He didn’t need to ask. He’d recalled where he’d heard Beddoes’ name mentioned, and he knew the answer already.

‘He’s got the perfect name for an Eng. Lit. teacher,’ said Roote, laughing. ‘Johnson. Dr Sam Johnson. Do you know him?’

‘That’s when I made an excuse and left,’ said Pascoe.

‘Oh aye? Why was that?’ said Detective Superintendent Andrew Dalziel. ‘Fucking useless thing!’

It was, Pascoe hoped, the VCR squeaking under the assault of his pistonlike finger that Dalziel was addressing, not himself.

‘Because it was Sam Johnson I’d just been playing squash with,’ he said, rubbing his shoulder. ‘It seemed like Roote was taking the piss and I felt like taking a swing, so I went straight back inside and caught Sam.’

‘And?’

And Johnson had confirmed every word.

It turned out the lecturer knew his student’s background without knowing the details. Pascoe’s involvement in the case had come as a surprise to him but, once filled in, he’d cut right to the chase and said, ‘If you think that Fran’s got any ulterior motive in coming back here, forget it. Unless he’s got so much influence he arranged for me to get a job here, it’s all happenstance. I moved, he didn’t fancy travelling for supervision and the job he had in Sheffield came to an end, so it made sense for him to make a change too. I’m glad he did. He’s a really bright student.’

Johnson had been out of the country during the long vacation and so missed the saga of Roote’s apparent suicide attempt, and the young man clearly hadn’t bellyached to him about police harassment in general and Pascoe harassment in particular, which ought to have been a point in his favour.

The lecturer concluded by saying, ‘So I got him the gardening job, which is why he’s out there in the garden, and he lives in town, which is why you see him around town. It’s coincidence that makes the world go round, Peter. Ask Shakespeare.’

‘This Johnson,’ said Dalziel, ‘how come you’re so chummy you take showers together? He fag for you at Eton or summat?’

Dalziel affected to believe that the academic world which had given Pascoe his degree occupied a single site somewhere in the south where Oxford and Cambridge and all the major public schools huddled together under one roof.

In fact it wasn’t Pascoe’s but his wife’s links with the academic and literary worlds which had brought Johnson into their lives. Part of Johnson’s job brief at MYU was to help establish an embryonic creative writing course. His qualification was that he’d published a couple of slim volumes of poetry and helped run such a course at Sheffield. Charley Penn, who made occasional contributions to both German and English Department courses, had been miffed to find his own expression of interest ignored. He ran a local authority literary group in danger of being axed and clearly felt that the creative writing post at MYU would have been an acceptable palliative for the loss of his LEA honorarium. Colleagues belonging to that breed not uncommon in academia, the greater green-eyed pot-stirrer, had advised Johnson to watch his back as Penn made a bad enemy, at a physical as well as a verbal level. A few years earlier, according to university legend, a brash young female journalist had done a piss-taking review of the Penn oeuvre in Yorkshire Life, the county’s glossiest mag. The piece had concluded, ‘They say the pen is mightier than the sword, but if you have a sweet tooth and a strong stomach, the best implement to deal with our Mr Penn’s frothy confections might be a pudding spoon.’ The following day Penn, lunching liquidly in a Leeds restaurant, had spotted the journalist across a crowded dessert trolley. Selecting a large portion of strawberry gateau liberally coated with whipped cream, he had approached her table, said, ‘This, madam, is a frothy confection,’ and squashed the pudding on to her head. In court he had said, ‘It wasn’t personal. I did it not because of what she said about my books but because of her appalling style. English must be kept up,’ before being fined fifty pounds and bound over to keep the peace.