Полная версия

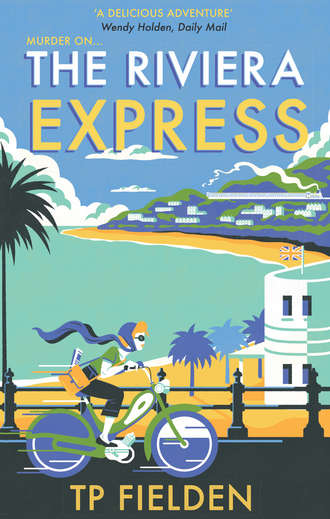

The Riviera Express

‘Werm coddit?’

‘Ur, nemmer be.’

‘C’rubble.’

Miss Dimont was too absorbed by the drama to pay much attention to these linguistic dinosaurs and their game of semantic shove-ha’penny; she sidled back to the railway carriage and then, pausing for a moment, heart in mouth, stepped aboard.

The silent Pullman coach was the dernier cri in luxury, a handsome relic of pre-war days and a reassuring memory of antebellum prosperity. Heavily carpeted and lined with exotic African woods, it smelt of leather and beeswax and smoke, its surfaces uniformly coated in a layer of dust so fine it was impossible to see: only by rubbing her sleeve on the corridor’s handrail did the house-proud reporter discover what all seasoned railway passengers know – that travelling by steam locomotive is a dirty business.

She cautiously advanced from the far end of the carriage towards the dead man’s compartment, her journalist’s eye taking in the debris common to the end of all long-distance journeys – discarded newspapers, old wrappers, a teacup or two, an abandoned novel. On she stepped, her eyes a camera, recording each detail; her heart may be pounding but her head was clear.

Gerald Hennessy sat in the corner seat with his back to the engine. He looked pretty relaxed for a dead man – she wondered briefly if, called on to play a corpse by his director, Gerald would have done such a convincing job in life. One arm was extended, a finger pointing towards who knows what, as if the star was himself directing a scene. He looked rather heroic.

Above him in the luggage rack sat an important-looking suitcase, by his side a copy of The Times. The compartment smelt of . . . limes? Lemons? Something both sweet and sharp – presumably the actor’s eau de cologne. But unlike Terry Eagleton Miss Dimont did not cross the threshold, for this was not the first death scene she had encountered in her lengthy and unusual career, and from long experience she knew better than to interfere.

She looked around, she didn’t know why, for signs of violence – ridiculous, really, given Terry’s confident reading of the cause of death – but Gerald’s untroubled features offered nothing by way of fear or hurt.

And yet something was not quite right.

As her eyes took in the finer detail of the compartment, she spotted something near the doorway beneath another seat – it looked like a sandwich wrapper or a piece of litter of some kind. Just then Terry’s angry face appeared at the compartment window and his fist knocked hard on the pane. She could hear him through the thick glass ordering her out on to the platform and she guessed that the police were about to arrive.

Without pausing to think why, she whisked up the litter from the floor – somehow it made the place look tidier, more dignified. It was how she would recall seeing the last of Gerald Hennessy, and how she would describe to her readers his final scene – the matinée idol as elegant in death as in life. Her introductory paragraph was already forming itself in her mind.

Terry stood on the platform, red-faced and hopping from foot to foot. ‘Thought I told you to call the police.’

‘Oh,’ said Miss Dimont, downcast, ‘I . . . oh . . . I’ll go and do it now but then we’ve got another—’

‘Done it,’ he snapped back. ‘And, yes we’ve got another fatality. I’ve talked to the desk. Come on.’

That was what was so irritating about Terry. You wanted to call him a know-it-all, but know-it-alls, by virtue of their irritating natures, do not know it all and frequently get things wrong. But Terry rarely did – it was what made him so infuriating.

‘You know,’ he said, as he slung his heavy camera bag over his shoulder and headed towards his car, ‘sometimes you really can be quite dim.’

*

Bedlington-on-Sea was the exclusive end of Temple Regis, more formal and less engagingly pretty than its big sister. Here houses of substance stood on improbably small plots, with large Edwardian rooms giving on to pocket-handkerchief gardens and huge windows looking out over a small bay.

Holidaymakers might occasionally spill into Bedlington but despite its apparent charm, they did not stay long. There was no pub and no beach, no ice-cream vendors, no pier, and a general frowning upon people who looked like they might want to have fun. It would be wrong to say that Bedlingtonians were stuffy and self-regarding, but people said it all the same.

The journey from the railway station took no more than six or seven minutes but it was like entering another world, thought Miss Dimont, as she and Herbert puttered behind the Riviera Express’s smart new Morris Minor. There was never any news in Bedlington – the townsfolk kept whatever they knew to themselves, and did not like publicity of any sort. If indeed there was a dead body on its streets this afternoon, you could put money on its not lying there for more than a few minutes before some civic-minded resident had it swept away. That’s the way Bedlingtonians were.

And so Miss Dimont rather dreaded the inevitable ‘knocks’ she would have to undertake once the body was located. Usually this was a task at which she excelled – a tap on the door, regrets issued, brief words exchanged, the odd intimacy unveiled, the gradual jigsaw of half-information built up over maybe a dozen or so doorsteps – but in Bedlington she knew the chances of learning anything of use were remote. Snooty wasn’t in it.

They had been in such a rush she hadn’t been able to get out of Terry where exactly the body was to be found, but as they rounded the bend of Clarenceux Avenue there was no need for further questions. Ahead was the trusty black Wolseley of the Temple Regis police force, a horseshoe of spectators and an atmosphere electric with curiosity.

At the end of the avenue there rose a cliff of Himalayan proportions, a tower of deep red Devonian soil and rock, at the top of which one could just glimpse the evidence of a recent cliff fall. As one’s eye moved down the sharp slope it was possible to pinpoint the trajectory of the deceased’s involuntary descent; and in an instant it was clear to even the most casual observer that this was a tragic accident, a case of Man Overboard, where rocks and earth had given way under his feet.

Terry and Miss Dimont parked and made their way through to where Sergeant Hernaford was standing, facing the crowd, urging them hopelessly, pointlessly, that there was nothing to see and that they should move on.

The sergeant spoke with forked tongue, for there was something to see before they went home to tea – there, under a police blanket, lay a body a-sprawl, as if still in the act of trying to save itself. But it was chillingly still.

‘Oh dear,’ said Miss Dimont, conversationally, to Sergeant Hernaford, ‘how tragic.’

‘’Oo was it?’ said Terry, a bit more to the point.

Hernaford slowly turned his gaze towards the official representatives of the fourth estate. He had seen them many times before in many different circumstances, and here they were again – these purveyors of truth and of history, these curators of local legend, these nosy parkers.

‘Back be’ind the line,’ rasped Hernaford in a most unfriendly manner, for just like the haughty Bedlingtonians he did not like journalists. ‘Get back!’

‘Now Sergeant Hernaford,’ said Miss Dimont, stiffening, for she did not like his tone. ‘Here we have a man of late middle age – I can see his shoes, he’s a man of late middle age – who has walked too close to the cliff edge. When I was up there at the top last week there were signs explicitly warning that there had been a rockfall and that people should keep away. So, man of late middle age, tragic accident. Coroner will say he was a BF for ignoring the warnings; the Riviera Express will say what a loss to the community. An extra paragraph listing his bereaved relations, there’s the story.

‘All that’s missing,’ she added, magnificently, edging closer to the sergeant, ‘is his name. I expect you know it. I expect he had a wallet or something. Or maybe one of these good people—’ she looked round, smiling at the horseshoe but her words taking on a steely edge ‘—has assisted you in your identification. He has clearly been here for a while – your blanket is damp and it stopped raining an hour ago – so in that time you must have had a chance to find out who he is.’

She smiled tightly and her voice became quite stern.

‘I expect you have already informed your inspector and, rather than drive all the way over to Temple Regis police station and take up his very precious time getting two words out of him – a Christian name and a surname, after all that is all I am asking – I imagine you would rather he did not complain to you about my wasting his very precious time.

‘So, Sergeant,’ she said, ‘please spare us all that further pain.’

It was at times like this that Terry had to confess she may be a bit scatty but Miss Dimont could be, well, remarkable. He watched Sergeant Hernaford, a barnacle of the old school, crumble before his very eyes.

‘Name, Arthur Shrimsley. Address, Tide Cottage, Exbridge. Now move on. Move on!’

Judy Dimont gazed owlishly, her spectacles sliding down her convex nose and resting precariously at its tip. ‘Not the Arthur . . .?’ she enquired, but before she could finish, Terry had whisked her away, for Hernaford was not a man to exchange pleasantries with – that was as much as they were going to get. As they retreated, he pushed Miss Dimont aside with his elbow while turning to take snaps of the corpse and its abrasive custodian before pulling open the car door.

‘Let’s go,’ he urged. ‘Lots to do.’

Miss Dimont obliged. Dear Herbert would have to wait. She pulled out her notebook and started to scribble as Terry noisily let in the clutch and they headed for the office.

Already the complexity of the situation was becoming clear; and no matter what happened next, disaster was about to befall her. Two deaths, two very different sets of journalistic values. And only Judy Dimont to adjudicate between the rival tales as to which served her readers best.

If she favoured the death of Gerald Hennessy over the sad loss of Arthur Shrimsley, local readers would never forgive her, for Arthur Shrimsley had made a big name for himself in the local community. The Express printed his letters most weeks, even at the moment when he was stealing their stories and selling them to Fleet Street. Rudyard Rhys, in thrall to Shrimsley’s superior journalistic skills, had even allowed him to write a column for a time. But narcissistic and self-regarding it turned out to be, and of late he was permitted merely to see his name in print at the foot of a letter which would excoriate the local council, or the town brass band, or the ladies at the WI for failing to keep his cup full at the local flower show.

There was nothing nice about Arthur Shrimsley, yet he had invented a persona which his readers were all too ready to believe in and even love. His loss would be a genuine one to the community.

On the other hand, thought Miss Dimont feverishly, as Terry manoeuvred expertly round the tight corner of Tuppenny Row, we have a story of national importance here. Gerald Hennessy, star of Heroes at Dawn and The First of the Few, husband of the equally famous Prudence Aubrey, has died on our patch. Gerald Hennessy!

The question was, which sad passing should lead the Express’s front page? And who would take the blame when, as was inevitable, the wrong choice was made?

THREE

It is remarkable, thought Miss Dimont, as her Remington Quiet-Riter rattled, banged, tinged and spat out page after page of immaculately typed copy addressing the recent rise in the death rate of Temple Regis. It really is remarkable . . .

Her typing came to a halt while she completed the thought. It’s remarkable how when there’s an emergency everybody just melts away. Here I am, writing one of the greatest scoops this newspaper has ever been lucky enough to have, and with press day looming, and everyone’s gone home.

She was right to feel nettled. The newsroom resembled the foredeck of the Mary Celeste, with all the evidence of apparent occupancy but none of the personnel. It was barely six o’clock but the crew of this ghost ship had jumped over the side, leaving Miss Dimont and Terry Eagleton alone to steer it to safety. Call it cowardice in the face of a major story, call it what you like, they’d all hopped it.

Around her, tin ashtrays still gave off the malodorous evidence that people once worked here. Teacups were barely cold. Someone had forgotten to put away the milk. Someone else had forgotten to shut the windows – strictly against company regulations – and the soft late summer breeze caused the large sign over the editorial desks to gently undulate, as if a punkah wallah had been employed especially to fan Miss Dimont’s fevered brow.

This sign was Rudyard Rhys’s urgent imprecation to staff to do their duty. ‘Make It Fast,’ he had written, ‘Make It Accurate.’ To which some wag had added in crayon, ‘Make It Up.’

There were wags aplenty at the Express. In the corner by Miss Dimont’s desk was a gallery of hand-picked photographs, a rich harvest of the paper’s weekly editorial content, which showed off the town’s newly-weds. For some reason the office jokers had chosen to pick the ugliest and most ill suited of couples – brides with snaggly teeth, grinning grooms recently released from the asylum. It was called the ‘Thank Heavens!’ board – thank heavens they found each other!

This joke had been running for a good few years and it was remarkable that on this evidence, in beauteous Temple Regis, there could be quite so many people – parents now, grandparents even – making such a lacklustre contribution to the municipality’s gene pool. It was rather a cruel joke of which Miss Dimont did not approve.

Turning away, she ladled in some extra paragraphs of glowing praise to the life and achievements of Arthur Shrimsley, adding a few of her own jokes – ‘His life was enriched by the sight of a good story’ (he stole enough of them from the Express and peddled them to Fleet Street). ‘He enjoyed the very sight of a typeface’ (if it showed his name in big enough print). ‘He was fearless’ (rude), ‘adept’ (as thieves so often are), ‘a consummate diplomat’ (liar) . . . ‘wise’(bore).

Gerald Hennessy she had already dispatched to the printer – a full page, motivated in part by his fame and the shock of the death of one so esteemed in humble Temple Regis, but also from a sense of personal loss: Miss Dimont had of course never met the actor before their recent silent encounter, but like all his fans, she felt she knew him intimately. There was something in his character as a human being which informed the heroic parts he played, her Remington had tapped out – instinctively his many admirers knew him to be the right choice to represent the dead and the dying of the recent war, as well as the nimble, the bold and the picaresque. It truly was a great loss to the nation and Miss Dimont, in writing this first of many epitaphs, captured the spirit of the man con brio.

The tumult from her typewriter finally ceased and, after a reflective pause, Miss Dimont fetched out the oilskin cover to put it to bed for the night. She had missed her choir practice, but then she already knew by heart the more easily accomplished sections of the Fauré Requiem with which the Townswomen’s Guild Chorus would be serenading Temple townsfolk in a fortnight’s time. She went along as much for the company as anything else, for Miss Dimont was a most able sight-reader with a melodious contralto that any choirmaster would give his eye teeth for. She did not need to practise.

She heaved a sigh of relief that it was over. How she would have hated to work on a daily newspaper, where deadlines assail one every twenty-four hours and there is no time to breathe! As she gathered up her things, her eyes travelled round the abandoned newsroom, about the most dreary working environment one could possibly imagine, and yet the very place where history was made. Or if not made, then recorded – for just as there is no point in climbing Mount Everest if there is no one there to chronicle it, so too what pleasure can there be in winning Class 1 Chrysanthemums (incurved) if not to rub their competitors’ nose in it? All human life was here, recorded in detail by the diligent Express.

The room was dusty, untidy, littered, and from the files of back copies lying under the window there rose the sour odour of drying newsprint. Desks were jammed together and covered in all the debris which goes with making a newspaper – rulers, pencils, litter galore, old bits of hot metal used as paperweights. Coats were slung over chairbacks as if their owners might shortly return.

Being a reporter had not been what Miss Dimont was put on this earth for – there had been another career, most distinguished, which preceded her present occupation – but she was a very good one. Except, of course, on occasions like the Regis Conservative Ball last winter, but if ever anyone had the temerity to bring that up, she rose above.

Now she must find Terry, beavering away in the darkroom, and get him to take her back to Bedlington, where, in their rush to get back to the office, her trusty Herbert had been abandoned.

As she made towards the photographic department, she heard the sound of a door opening, followed by a muffled squeak. Miss Dimont stopped dead in her tracks. There was nobody else in the building except her and Terry – what was that rustling sound, that parrot-like noise?

She swung round to be faced by a ghostly apparition – white-faced, grey-haired, long claw-like fingers, a rictus of a smile upon its features.

‘Purple,’ it whispered.

‘Oh, hello, Athene,’ started Miss Dimont, ‘you gave me such a fright.’

Then, like the Queen of Sheba, Athene Madrigale sailed into the room, her aura wafting before her in the most entrancing way. She was rarely seen in daylight – indeed she was rarely seen at all – but despite her advanced age she remained one of the pillars upon which the Riviera Express had built its reputation. For Athene wrote the astrology column.

What most Express readers turned to each Friday morning, immediately after looking to see who’d died or been had up in court, were Athene’s stars. In Temple Regis, you never had a bad day with Athene.

‘Sagittarius: Oh! How lucky you are to be born under this sign,’ she would trill. ‘Nothing but sunshine for you all week!

‘Capricorn: All your troubles are behind you now. Start thinking about your holidays!

‘Cancer: Someone has prepared a big surprise for you. Be patient, it may take a while to appear, but what pleasure it will bring!’

These were not the scribblings of a simpleton but rare emanations from under the deeply spiritual cloak which adorned Athene Madrigale’s person. Though not quite as others – her rainbow-hued costumes set her apart from the average Temple Regent, not to mention the turquoise fingernails and violet smile – she exuded nothing but beauty and calm. It is quite likely her name was not Athene, but nobody felt the need to question it while she predicted such wonderful things for the human race.

Equally, nobody was quite sure where Athene lived – some said in a mystical bubble on the roof of the Riviera Express – but what is certain is that she needed the protection of night to save her from being swamped by an adoring public, her aura too precious to be jostled. It is true Miss Dimont encountered her from time to time, but only because she would return late from council meetings to diligently write into the night until her work was done. Most reporters on late jobs kept it in their notebook and typed it up next day.

‘Purple,’ whispered Athene again.

‘But going green?’ replied Miss Dimont.

‘Mercifully for you, dear.’

‘It’s been a something of a day, Athene.’

‘I can tell, my dear, do you want to sit down and talk about it?’

This was a rare invitation and one not to be denied. The strain of the day’s activities had taken its toll on the reporter and she was grateful for a sympathetic ear. Almost as if by magic a cup of hot, sweet tea appeared in front of her and Athene arranged her rainbow clothes in a most attractive way on the seat opposite, the manner in which she did it suggesting she had all the time in the world. Even though she had yet to write the astrology page!

‘It’s not the first time I’ve seen dead bodies,’ started Miss Dimont.

‘No, dear. That chemist with the pill-making machine.’

‘Yes.’

‘Lady Hellebore and the gardener.’

‘I’d almost forgotten that.’

‘The Temple twins.’

‘So many, oh dear . . .’

Athene knew when to move on. ‘What is it, then, Judy? What’s wrong?’

‘I don’t know,’ came the reply. ‘Maybe it’s seeing two fatalities in one day. Two such different people – one so loved, the other so hated. But both lives at an end, equally, as if God cannot differentiate between good and evil.’

‘That’s not really what’s upsetting you, though,’ said Athene gently, for she was gifted with a greater understanding of people’s travails. ‘It’s something else.’

Miss Dimont stirred her tea. ‘Yes,’ she said finally. ‘I just feel something’s wrong.’

‘Like you did with the twins?’

‘Oh . . . oh yes, something is wrong. I’ve been over it while I was writing my copy but I can’t see what it is. There was something about Gerald Hennessy, he sat there so calmly, but he was pointing – pointing!’

‘At what, dear?’

‘Well, nothing. I thought when I looked at him that he was accusing someone. There was just that look on his face. Somehow trying to say something, but not quite managing it.’

‘Go on.’

‘And then, when we went to Bedlington, the way he – oh, did you know Arthur Shrimsley was dead?’

‘Couldn’t happen to a nicer chap,’ said Athene crisply, her perpetual sun slipping over the horizon for a brief second.

‘Mm?’ said Miss Dimont, not quite believing such harsh words could steal from the benign countenance. ‘Well, anyway, there was just something about it all. It wasn’t just Sergeant Hernaford, though he was obnoxious, it wasn’t even the way the body was lying. Just something about the way Mr Shrimsley had managed to get through that barrier right out on to the cliff edge. It didn’t seem . . . logical. It didn’t add up.’

Athene did not know what Judy was talking about, but she did know how to refresh a teacup. Once done, she sat there expectantly, waiting for the next aperçu.

‘And, er, that’s it really’ said Miss D, disappointingly.

Miss Madrigale was far too conversant in the ways of the parallel universe to see a complete lack of evidence in what she had just heard. There was something here, most certainly. She was glad to see that she had eradicated the purple from Miss Dimont’s aura and that it was almost completely restored to a healthy green.

‘You’ve been such a help, Athene,’ said Judy gratefully, but as the words formed in her mouth, she awoke to the fact that Athene had completely disappeared.

‘Still ’ere?’ barked Terry Eagleton, who had blustered into the room with a time-for-a-pint look on his face, startling Athene away.

‘Yes. And you’ve got to take me back to Bedlington to pick up Herb— the moped.’

‘Want to see what we’ve got?’ asked Terry, eager as ever to show off the fruits of his day’s labours. ‘Some great shots!’

‘Pictures of dead bodies? Printed in the Express?’ marvelled Miss Dimont. ‘Never in a month of Sundays, Terry, not while King Rudyard sits upon his throne!’

‘Yers, well. ’ Terry sniffed. ‘I’ll keep them back for the nationals. Take a look.’

And since Judy Dimont relied on Terry for her lift back to Bedlington, she obliged. The pair walked through into the darkroom, where, hanging from little washing lines and attached by clothes pegs, hung the 10 x 8 black-and-white prints which summed up the day’s events. They were not a pretty sight.