Полная версия

Dark Resurrection

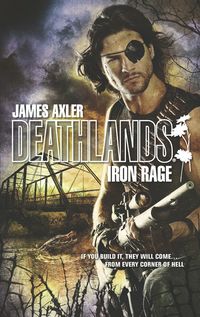

Ryan glanced at the exhausted human forms hunched on the benches around him. In the deck lights, the slaves’ filthy cheeks were streaked by tears, their lips trembling, their eyes wide with fear and panic at the prospect of an unknown fate.

Faced with the self-same prospect, his companions had drawn on the last of their physical and mental reserves, turning hard-eyed, resolute, deadly focused. Like Ryan, Mildred, Doc, Jak, Krysty and J.B. were a breed apart, their spirits tempered in the furnace of continual conflict and bodily risk. Unlike their Deathlander fellow slaves, they had little interest in finding a comfortable hole to hunker down in, nor in shouldering leather traces and dragging an iron-tipped plow over rocky soil, nor in crawling through the radioactive nukeglass massifs in search of predark spoils, nor in selling their considerable fighting skills to the highest-bidding baron. They were addicted to the kind of absolute freedom only the hellscape could provide.

Aboard Tempest, in what now seemed like another life, when Doc had proposed they join Harmonica Tom on a southern hemisphere voyage of discovery, none of them ever dreamed it would be undertaken in chains and at the point of a lash.

Now the impossible situation in which Ryan and his comrades found themselves trapped was about to change.

Maybe for the worse.

Maybe not.

In the latter they saw a crack of daylight.

Ryan nudged Mildred gently with his elbow, nodded toward the crescent of lights, and said, “So, that’s what the world looked like before hellday?”

“Pretty much,” she replied.

From the bench on the far side of Mildred, J.B. leaned forward and asked, “Where in nukin’ hell are we? That’s all still Mex, right?”

“I think it’s Veracruz,” the twentieth-century, physician freezie said. “Or maybe Tampico. They were the two closest big port cities.”

One of the Matachìn deck-watch leaned in under the sheet metal awning beside them. He was tricked out in full battle armor. Hanging by his hands on the pipe strut, he unleashed armpit stench with both barrels. There was spattered blood on the canvas scabbard of his gut-hook machete. It was still wet, and it was most certainly human. Slaves too weak to row routinely got the long edge across the backs of their necks before they were tossed over the side like so much garbage. A crazy triumphant look in his eyes, the pirate spoke rapid-fire down at Mildred. Overhearing the words, the Matachìn idling nearby looked on in amusement.

“What did the bastard say to you?” Ryan asked.

Mildred translated. “He said we’re looking at Veracruz City.”

“He said more than that,” J.B. prompted.

“Yeah, he did,” she admitted. “He said next to his world, Deathlands is nothing but shit, and that we Deathlanders will always be shit.”

“An assessment that might have carried more weight,” Doc remarked aridly from a seat on the bench directly behind them, “had his own hairstyle not been adorned with dried sea gull excreta.”

“You’re absolutely right,” Ryan told the pirate. “We’re shit and you’re not.”

The Matachìn scowled and as he did so his right hand dropped to his hip and the pommel of his braided leather lash. English was beyond him, but tone transcended the language barrier.

Mildred spoke up quickly, putting Ryan’s remark into Spanish. Evidently the sarcasm was lost in translation.

With a satisfied sneer, the pirate turned back to his shipmates.

As the ship angled closer to shore, the lay of the coast gradually revealed itself. The curve of a southward-pointing peninsula became distinct from the landmass immediately behind it. The tug beelined for a blinking green beacon that marked the deep channel at the tip of the breakwater. When the ship rounded the bend into the protection of the harbor, they hit the wall of trapped heat and suffocating humidity radiating off the land.

The ship’s horn blasted overhead; the sister ships behind chimed in, as well, announcing the Matachìn convoy’s triumphant return to what Ryan could only guess was its point of origin.

In the lee of the peninsula, under scattered bright lights on tall stanchions, were the remains of a commercial shipyard—docks and cargo cranes. The scale of the development dwarfed what they had seen at Port Arthur ville. The structures hadn’t escaped Armageddon unscathed, though. It looked like they had been slammed by tidal waves or earthquakes. Most of the metal-frame industrial buildings were flattened to their concrete pads. Towering cargo cranes canted at odd angles; some had toppled into the water. The enormous docks were broken, wide sections of decking were missing; moored to the remnants were a hodge-podge of small trading vessels. Beyond the docks, where the peninsula met the mainland, stood a power plant that was fully operational. Floodlights illuminated clouds of smoke or steam from a trio of tall stacks. Over the noise of the diesels, the complex emitted a steady, high-pitched hum.

The lead tug continued, hugging the inside of the peninsula, passing within a hundred yards of another immense structure—a fortress made of heavily weathered, light gray stone, also dramatically lit. Apparently constructed on an offshore island, it was connected to the mainland by a low, stone bridge. Above its crenellated battlements, at either end of the enclosed compound, were cylindrical observation towers. Huge iron anchor rings hung in a row just above the waterline. In front of the high-arched entrance gate, small motor launches were tied up to mooring cleats. Eroded stone sentry boxes bracketed the gate.

The mini-island fortress was a time-worn anachronism, but it had been built to last; it had survived nukeday virtually intact, whereas the twentieth-century artifacts that surrounded it had not.

“It’s an old Spanish fort from colonial days,” Doc ventured. “Probably six hundred or more years old. Those massive, triangular blockhouses outside the corners of the bastion walls are called ravelins. They were designed to defend the main perimeter from attack by offering a protected position for flanking fire. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries Spaniards used stone forts like that to store gold and silver mined from the New World. It could also defend the city from pirates and foreign invaders—French, English, American.”

Even bathed in hard, bright light, evil seem to emanate from the structure, from the very seams in its masonry.

Ancient squatting evil.

A consequence of the uncounted thousands who had died as prisoners in its belly, between its teeth, under its claws.

“The question is, what is it now?” Mildred said.

“Those cannons sticking out of the battlements sure as hell aren’t six-hundred-year-old muzzleloaders,” J.B. said. “If I had to guess I’d say they’re at least 106 mm with mebbe a one-mile range. That means nobody comes in or goes out of the harbor without coming under their sights.”

As the tug motored through the sheltered waters of the harbor, past the fort’s arched gate, a gaggle of armed men spilled through it, waving and cheering in welcome. They didn’t look anything like the Matachìn. No dreads. No battle armor. They weren’t wearing uniforms as such, more like insignia. They all had crimson sashes over their right shoulders and opposite hips, and they wore off-white straw cowboy hats with rolled brims. Their shoulder-slung weapons were different from what the Matachìn carried. The wire-stocked, stamped-steel submachine guns were much more compact, like Uzi knock-offs, with the mags inside the pistol grips. Men in crimson sashes continued to pour out of the gate, onto the dock.

“Sec man garrison,” Ryan said flatly.

Fireworks whistled from the battlements, arcing high into the black sky, and there exploding into coruscating patterns of green, gold and red.

The tug chugged on, turning left for the nearby mainland.

Looking over his shoulder at the wreckage of the peninsula, Ryan guessed that it had taken the brunt of nukeday tidal waves, in effect absorbing most of the energy before it reached the city on the inside of the harbor.

Off the bow, Veracruz glowed incandescent against the black-velvet sky. The one-eyed warrior could make out individual pinpoints of light from the upper story windows of the tallest buildings. At the edge of the city, a long pier jutted into the water; it was overlooked by a lighthouse.

When the tug came within four hundred yards of the pier, Ryan saw it was packed end to end; thousands of people had assembled and were waiting for them to arrive. Another hundred yards closer and he could see that the overloaded dock was just the tip of the crowd, which stretched unbroken, back into the brightly lit city streets. There was no telling how far back it went. The throng was like a single entity, a vast amoeba-thing in constant, chaotic motion, only kept from spilling out in all directions by the building walls on either side. Between celebratory blasts of the ships’ horns, Ryan heard yelling and blaring fragments of music. The din got even louder as the tug pulled alongside the pier. The music—caterwaul singing backed by frenzied fiddle, drums and guitar—boomed down from loudspeakers mounted on the lamp posts.

A sea of sweaty, brown faces greeted them.

The wildly excited citizens of Veracruz waved Day-Glo-colored plastic pennants emblazoned with unintelligible symbols. They held ten times larger-than-life-size papier-mâché heads on long poles, which they jigged up and down. Some of the paper sculptures had flat noses, ornate headdresses and leering mouths lined with cruel fangs. The colors were bizarre instead of lifelike—glistening green or pink skins, pointed black tongues, insane red and purple eyes with yellow pupils. Ryan strained to read the words written across their neckplates: Atapul the First; Atapul the Second; and so on, up to Atapul the Tenth.

They were names, he figured.

Ryan had no clue what the stylized images represented, whether they were gods or barons, but the meaning of some of the other sculpted faces was all too apparent. Bobbing in front of him on pikes were gigantic human heads with a ghastly bluish pallor, bleeding from nose, eyes and mouths. Cheeks and foreheads were speckled with red dots. Their expressions were fixed in rictus agony and terror.

Plague masks.

Plague like the one that had struck Padre Island.

Mildred squeezed his arm hard to get his attention, then raised her manacled hands to point toward the landward, lighthouse end of the pier.

There, not thirty yards away, on the end of a wooden pole, ten times life size, was Ryan’s own face, or a close approximation thereof. It was crudely rendered and painted, but all the pertinent details were there: the black eye patch, the scar that split his brow, the dark curly hair, the single surviving eye, the bearded cheeks, the square chin. The only difference was, the patch and scar had been reversed on the sculpture, as if he was staring into a mirror.

There were more of the giant, eye-patch faces spaced here and there among the seething throng.

“What the fuck?” Ryan said.

Chapter Two

Harmonica Tom stood at the helm of Tempest, feathering the engine’s throttle to maintain a constant safe distance from the row of ship lights in front of him. He ran the forty-foot vessel blacked-out, as he had done every night for the last three weeks, every night since he’d escaped from Padre Island. Finding the pirate convoy after dark was a piece of cake for the seasoned skipper. The six target boats were always lit up, mast, bow and stern; this to help keep them from crashing into one another.

During the day, Tom had to lay back in his pursuit for fear a crow’s-nest lookout would glimpse his mast tops astern. The last thing he wanted was for part of the fleet to peel off and double back to check out who was following its wake. The seagoing trader was sure they’d have no trouble recognizing Tempest: he’d already used it to kick their asses once. Unfortunately, he’d only managed to sink a single ship, while damaging two others. The fallback in pursuit meant he had to do some zigging and zagging to find the convoy again after sundown.

No problem this night, though.

The Matachìn ships were under engine power; even the slave galley tugs were burning diesel. And they were heading in toward the coast, making for the corona of shimmering lights low on the horizon.

By Tom’s map reckoning, it had to be Veracruz.

It was starting to look like the fire talkers’ stories were all true. That there really was a wider and more prosperous world than Deathlands, existing invisibly, simultaneously, from nukeday forward.

When he had first heard the tales of civilization’s survival in the south, Tom had wanted to get in on the ground floor, to be the first to establish peaceful commerce, to forge trade links with the more advanced culture, and thereby get his hands on some of its fabled material wealth. But after seeing what the dreadlocked emissaries of that culture had done to Padre Island, the entrepreneurship fantasies vanished. Payback had become his single-minded goal.

And payback was his forte.

Like other Deathlands traders, Harmonica Tom Wolf had committed his share of morally questionable deeds over the years—some might even call them “atrocities.” It was part of staying in business, and staying alive. He had systematically eliminated rivals trying to encroach on his territory. He had closed deals with hot lead and cold steel instead of smiles and handshakes. He had transported cargos of uncut jolt and high explosives without thinking twice. He had never purposefully messed with women and kids, though. And when he had sent another trader or coldheart on the last train west, it had always been a chill-or-be-chilled situation, and it was usually face-to-face, if not nose-to-nose.

The horror he had seen at Padre had transformed him, and not in a good way. Images of the dead and dying in that shantyville were branded into the root of his brain. Whenever he managed to grab a few winks of sleep, they invariably shook him awake. He came to gasping for air, spitting mad, fingers clawing for the butt of his stainless-steel .45 Smith wheelgun, looking around for someone to chill.

The Nuevo-Texicans’ passing hadn’t been quick or clean, not like getting shot or stabbed or fragged by shrap. They had disintegrated from the inside out, cooked in their skins by fever, laying helpless in pools of their own bodily waste. These were folks he’d done business with for years. Folks he respected. He even knew their kids by name. Kids who’d died the same awful way. He’d had three weeks to stew over what had happened to them, and why.

From the evidence on the scene it looked like disease had ravaged more than half the population before the pirates showed up. Tom had never seen or heard of anything like it. Of the islanders who were stricken by the plague, no one recovered. It was one hundred percent debilitating and one hundred percent fatal. And that wasn’t the whole story. The outbreak had peaked just in time for the naval assault and invasion.

An unlucky turn of fate?

Harmonica Tom didn’t think so.

The Nuevo-Texicans were anything but pushovers. Every man, woman and child older than the age of eight could handle a blaster, and they had plenty of ammo and heavy automatic weapons. Through cagey barter they had accumulated some explosives, too—they had a good stock of Claymore anti-pers mines. For thirty years the islanders had successfully defended their grounded freighter and its stores against all comers. The question was, could a small force of Matachìn have overwhelmed the hardened, battle-tested defenses and superior numbers without help from the plague?

Definitely not, Tom had concluded. The pirates lacked the manpower to take Padre Island hill by hill, and long-distance shelling alone couldn’t do the job.

Disease as a weapon of war, of conquest, of genocide wasn’t anything new in the history of the planet. Tom remembered reading about small pox–infected blankets somewhere in his shipboard collection of predark books. Long before Armageddon, they had been handed out to reservation Indians to make them sick and wipe them out. The how of what had happened at Padre was a mystery that might never be solved, but Harmonica Tom was damn well sure the appearance of the plague was no coincidence.

The objective of the invasion by sea hadn’t been simple, familiar robbery, either. The Matachìn had blown apart the beached freighter that contained all of the islanders’ worldly goods, and having done that, they just left it to burn, as if it held nothing worth stealing. The objective apparently had been the destruction of all life and property. Tom took that as an insult to Deathlands, and to the best of its hard-pressed survivors. Moreover, he took it as a personal affront.

And then there was the matter of Ryan Cawdor and his five companions.

No doubt about it, he had dragged those good folks into a world of trouble and hurt. They’d wanted to head east to off-load the 125-pound cache of C-4 they’d snatched, but he’d told them they’d get a better price if they sailed west and dealt with the Padre Islanders. When the shit hit the fan on Padre, things had broken badly for Cawdor and the others. They were still alive when Tom had hightailed it for Tempest, but the last he’d seen of them, they were pinned down by pirates who were closing in fast. If they had managed to live through the assault, they would have been taken as slaves for the galley ships. In the three weeks since Tom had made his solo escape, they could have all died at their oars.

Death en route was a definite possibility.

More than once he had come across big-ass sharks lazily schooling around a headless floating torso with flesh hanging from it in a pale, bloodless fringe. Every time he saw the rad-blasted black fins circling on the surface, he’d divert course to see if it was anyone he knew.

Harmonica Tom had a very straightforward rule for survival that had proved itself over the years: when the odds were good, hit; when the odds were shit, git.

No way could he fight the convoy at sea and hope to win. There were too many opposing vessels, and three of them had massive diesels and twice his speed. If he tried to engage them in open water with Tempest, he knew he’d be outmaneuvered in no time and once committed to the attack, he’d never escape.

In one sense, the farther south he sailed the longer the odds got; in another sense, they actually improved. Though he had penetrated deep into Matachìn territory, nobody in these parts had ever heard of Harmonica Tom. Off his ship he would be unrecognizable, even to the pirates he had outcaptained and outfought along the treacherous Texican shoals. And if the pirate cities were jam-packed with people like the fire talkers said, that gave him the advantage of invisibility. A man who was careful and quiet could get lost in a crowd.

From the angle of the ship lights relative to the shore, Tom figured the convoy was going to make its first landfall at Veracruz. He backed the throttle to idle but left the engine in gear, then lashed off the helm to maintain a steady course. He’d had three weeks to consider the best plan of action. What he’d come up with involved taking some big chances, but none of them were new.

It was called going for broke.

He opened and swung back the cockpit door, then turned to the box-fed, Soviet PKM pivot mounted on Tempest ’s stern rail. Unlocking the canvas-shrouded machine gun from its swivel, he carried it down the steep steps to the cabin. He removed the shroud, then fitted the weapon onto the sandbagged tripod already set up at the foot of the stairs. He opened the feed cover to make sure there wasn’t a round chambered. After angling the barrel up to cover the entryway above and cockpit beyond, he locked the elevation.

Tom scrambled up the stairs and attached the end of a steel trip wire to an eye-screw on the inside of the open door. Descending again, he fed the wire through other strategically placed eyes on the staircase, bulkhead wall and the back edge of the galley table on the far side of the tripod. He tested the run of the wire back and forth for smoothness, then inserted the free end of it through the weapon’s trigger guard. He depressed the trigger until the firing pin snapped on the empty chamber. Holding down the trigger, he looped the wire around it, pinning it as far back as it would go. Up the steps one more time, he pulled the cockpit door closed, which released the tension on the wire and allowed the trigger to snap back to ready position. Back beside the machine gun, he set the safety switch to “fire” and cocked the actuator, racking a live 7.62 mm round.

The next time the cockpit door was opened, the wire would draw tight; at the door’s full, outward arc, the pullback tension would break the trigger and hold it down. The PKM was a sweet blaster, low recoil, no muzzle climb to speak of. It would continue firing until it came up empty—one hundred rounds down the road. Or until someone shut the door. The chances of anyone doing that were slim, unless they were fucking bulletproof.

Tom buckled his holstered Model 625 revolver around his waist. From the galley table he picked up his pride and joy, a nine mill Heckler & Koch MP-5 SD-1 silenced machine pistol. The compact blaster had no rear stock. It weighed in at 7.5 pounds with a loaded, 32-round mag. He slipped the weapon’s quick-release lanyard over his neck; thus suspended, its plastic pistol grip hung even with his belly button. He had traded twenty gold-filled teeth for the mint H&K. Thanks to the widespread practice of dentistry before nukeday and the massive depopulation afterward, abandoned graveyards had become the new Klondike. Gold was slowly being accepted across Deathlands as a universal form of jack.

From a hook on the wall he grabbed a duct-tape-patched, olive-drab poncho and pulled it on over his head. The poncho left his arms free and draped low enough front and rear to keep both blasters out of sight. Though his skin was deeply tanned and weathered, he didn’t know if it was tanned enough to pass for native. To keep his face in shadow he donned a sweat-stained, frayed, olive-drab billcap. There wasn’t much he could do about hiding his sandy-colored, handlebar mustache, except to cut the damn thing off, and he wasn’t about to do that.

Shouldering a preloaded pack, he headed toward the bow, climbing the short flight of steps that led to the foredeck. Back out in the night air, he padlocked the forward companionway door behind him. Then he took a handpainted sign from the pack and wired it securely to the hasp.

Crude red letters on a white background read: Peligro. Danger. The middle of the sign was decorated with a childish skull and cross bones under which was another word: Plaga. Plague.

He made for the stern and jumped down into the cockpit. After padlocking the entry door, he hung a copy of the Danger sign on it. Even if the locals couldn’t read, he hoped the symbol of death would make them think twice before trying to break in. If not, anyone opening the door was going to get a big—and final—surprise.

The stash of C-4 was stowed in a secret compartment under the cabin’s deck. To find it, the surviving intruders would have to tear the ship apart, bulkhead by bulkhead. Tom figured to be back aboard long before that happened. Either that or chilled.

Off Tempest ’s starboard bow, the last ship in the pirate convoy was rounding the blinking green light marker and heading into the harbor. Tom untied the wheel and goosed the throttle, steering for the marker buoy. He throttled back again as he cleared the light, slowing to take in the harbor and the glowing city on the far side.

Amazing, he thought as he took in the panorama. Fucking amazing.

Distant horn blasts rolled over the water. They came from the pirate convoy, which was about a mile ahead, motoring along the inside curve of the peninsula at a sedate pace. As it passed in front of the battlements of a stone fort, a flurry of fireworks exploded over the harbor.