Полная версия

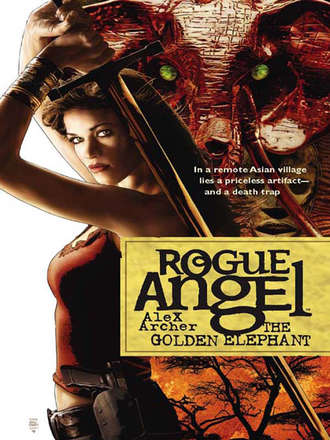

The Golden Elephant

“Uh, hey,” she called. “I’m afraid it’s not far enough. I need a little more rope here.”

She heard a musical laugh. It made its owner sound about fourteen. “So sorry,” the unseen voice said. “No can do.”

“What do you mean?” Annja almost screamed the words as water burst into the room to eddy around her shoes. “You aren’t going to leave me to drown?”

“Of course not. In a matter of a very few minutes the water will rise enough to float you up to where you can grasp the rope and climb out. A bit damp, perhaps, but none the worse for wear.”

Annja stared. The astonishing words actually distracted her from the floodwaters until they rose above the tops of her waterproofed shoes and sloshed inside them. Their touch was cold as the long-dead emperor’s.

“At least leave me my pack!” Annja shouted, jumping up and swiping ineffectually at the dangling rope. She only succeeded in making it swing. She fell back with a considerable splash.

“I’m afraid not,” the woman called. “You have to understand, Ms. Creed. There’re two ways to do things—the hard way and the easy way.”

Annja stood a moment with the water streaming past her ankles. The words were so ridiculous that her mind, already considerably stressed by the moment, simply refused to process them.

Then reality struck her. “Easy?” she screamed. “Not Easy Ngwenya?”

“The same. Farewell, Annja Creed!”

Annja stared. The chill water reached her knees. She stood, utterly overwhelmed by the realization that she had just been victimized by the world’s most notorious tomb robber.

2

Paris, France

“You’re kidding,” Annja said. “Who doesn’t like the Eiffel Tower?”

“It’s an excrescence,” Roux replied.

“Right,” she said. “So you preferred it when all you had to watch for in the sky was chamber pots being emptied on your head from the upper stories?”

“You moderns. You have lost touch with your natures. Ah, back in those days we appreciated simple pleasures.”

“Not including hygiene.”

Roux regarded her from beneath a critically arched white brow. “You display a most remarkably crabbed attitude for an antiquarian.”

“I study the period,” she said. “I’m fascinated by the period. But I don’t romanticize it. I know way too much about it for that. I wouldn’t want to live in the Renaissance.”

“Bah,” the old man said. But he spoke without heat. “There is something to this progress, I do not deny. But often I miss the old days.”

“And you’ve plenty of old days to miss,” Annja said. Which was, if anything, an understatement. When he spoke about the Renaissance, he did so from actual experience.

Roux was dressed like what he was—an extremely wealthy old man–in an elegantly tailored dove-gray suit and a white straw hat, his white hair and beard considerably more neatly barbered than his ferocious brows.

Annja had set down her cup. She sat with her elbows on the metal mesh tabletop, fingers interlaced and chin propped on the backs of her hands. She wore a sweater with wide horizontal stripes of red, yellow and blue over her well-worn blue jeans. A pair of sunglasses was pushed up onto the front of her hair, which she wore in a ponytail.

Autumn had begun to bite. The leaves on the trees along the Seine were turning yellow around the edges, and the air was tinged with a hint of wood smoke. But Paris café society was of sterner stuff than to be discouraged by a bit of cool in the air. Instead the sidewalks and their attendant cafés seemed additionally thronged by savvy Parisians eager to absorb all the sun’s heat they could before winter settled in.

She found herself falling back onto her current favorite subject. “I’m still miffed at what happened in Ningxia,” she said.

“ You’re miffed? I have had to answer to certain creditors after the shortfall in our accounts. Which was caused by your incompetence, need I remind you?”

“No. And anyway, that’s not true. I got the seal. I had it in my hands.”

“Unfortunately it failed to stay in your hands, dear child.”

“That wasn’t my fault! I trusted her,” Annja said.

“You trusted a strange voice which called down to you through a hole in the ground,” Roux said. “And you style yourself a skeptic, non? ”

Annja sat back. “I was kind of up against it there. I didn’t really have a choice.”

“Did you not? Really? But did you not eventually save yourself by following that vexatious young lady’s suggestion, and waiting until the water floated you high enough so you could climb the rest of the way out?”

“Only to find the witch had flown off in my helicopter. My. Helicopter, ” Annja said.

“Oh, calm down,” the old man said unsympathetically. “She did send a boat for you. Which she paid for herself.”

Annja sat back and tightly folded her arms beneath her breasts. “That just added insult to injury,” she said. The tomb robber had even left her pack. Without the seal. “Whose side are you on, anyway?”

“My own, of course,” Roux said. “Why be mad at me? I only point out things could have gone much worse. You might have seen Miss E. C. Ngwenya’s famous trademark pistols, for example.”

Annja slumped. “True.”

“And it never occurred to you,” Roux said, “simply to wait until the water lifted you high enough to climb out the hole directly, without handing over the object of your entire journey to a mysterious voice emanating from the ceiling?”

Annja blinked at him. “No,” she said slowly. “I didn’t think of that.”

She sighed and crumpled in her metal chair. “I pride myself in being so resourceful,” she said almost wonderingly. “How could it have deserted me like that?”

Roux shrugged. “Well, circumstances did press urgently upon you, one is compelled to admit.”

She shook her head. “But that’s what I rely on to survive in those situations. It’s not the sword. It’s my ability to keep my head and think of things on the spur of the moment!”

“Well, sometimes reason deserts someone like you,” Roux said.

For a moment Annja sat and marinated in her misery. But prolonged self-pity annoyed her. So she sought to externalize her funk. “It’s just losing such an artifact—the only trace of that tomb—to a plunderer like Easy Ngwenya. She just violates everything I stand for as an archaeologist. I’ve always considered her nothing better than a looter.”

She frowned ferociously and jutted her chin. “Now it’s personal.”

Roux set down his cup and leaned forward. “Enough of this. Now, listen. Your secret career is an expensive indulgence—”

“Which I never volunteered for in the first place!” Annja said.

“Details. The fact is, you have been burning money. As I have alluded to, certain creditors grow—insistent.”

Annja frowned thoughtfully. She could see his point. There was no denying her recent adventures had been costly. The rise of digital records and biometric identification hadn’t made official documentation more secure—the opposite, if anything. But full-spectrum false identification was expensive. And Annja relied greatly on fake ID to avoid having her secret career exposed by official nosiness.

She leaned back and crossed her legs. “Has Bank of America been making nasty phone calls?”

“Think less modern in methods of collection, and more Medici.”

“You haven’t been borrowing from Garin again?” Annya asked.

His lips compressed behind his neat beard. “It’s…possible.”

Garin Braden was a fabulously wealthy playboy. He was also Roux’s former protégé and he feared the miraculous reforging of the sword threatened his eternal life.

“I bet you’ve just had a bad streak at the gaming tables,” Annja said accusatorily. “Didn’t you get busted out of that poker tournament in Australia last month?”

“All that aside, we must improve what you Americans charmingly call cash flow.”

She sighed. “Tell me,” she said.

“Somewhere in the mountainous jungles of Southeast Asia there supposedly lies a vast and ancient temple complex. Within it hides a priceless artifact—a golden elephant idol with emerald eyes. I have been approached by a wealthy collector who wants it enough to pay most handsomely.”

“Who?”

“One who treasures anonymity,” Roux said.

“That’s a promising start,” Annja said, not bothering to hide the sarcasm in her voice. “So I take it all this mystery likewise precludes your at least running a credit check?”

“Sadly,” Roux said, “yes.”

He spread his hands in a dismissive gesture. “However, our client—”

“Let’s hold off on this our business until I’m actually signed on, shall we?” Annja said.

“ Our client has offered a handsome preliminary payment, as well as an advance against expenses.”

“The preliminary, at least, needs to be no-strings-attached,” Annja said.

Roux raised his eyebrow again.

“What?” Annja said.

“That would require substantial faith on the client’s part,” Roux said.

“So? Either he-she-it has faith in me, or doesn’t. If they’re not willing to believe in my integrity, then to heck with it. And why come to me, anyway, if that’s the case? If I’m not honest, there’s ten dozen ways I could chisel, from embezzling the expense account to selling to the highest bidder whatever it is this mystery guest wants me to get. There isn’t any guarantee I could give that could protect against that. If I’m a crook, what’s my guarantee worth?”

Roux looked as if he were bursting to respond. She glared him into silence.

“While we’re on the subject,” she said, “there’s not going to be any accounting for expenses incurred. For reasons I really hope you won’t make me explain out loud.”

He sipped his coffee and pulled a gloomy face. “You don’t ask for much, my dear child,” he said, “beyond the sun, the moon and perhaps the stars.”

“Just a star or two,” she said. “Anyway, you’re the one whining the exchequer might be forced to go to bed tonight without any gruel if little Annja doesn’t hie herself off to Southeast Asia and do something certainly arduous, probably dangerous and more than likely illegal. You should be happy to ask for the best no-money-back terms available.”

“I don’t want to scare the client off,” Roux said.

“This strikes me as skirting pretty close to pot-hunting,” Annja said. “The jade-seal affair already came too close.”

“But you’ve done similar things in the past,” Roux said. “And after all, who better to ensure the Golden Elephant is recovered in a…sensitive way rather than ripped from the earth by a tomb-robber?”

He turned his splendid head of silver hair to profile so he could regard her sidelong with slitted eyes. “Or would you prefer to leave the field open to, say, the likes of Her Highness, E. C. Ngwenya?”

“Quit with the psychological manipulation,” she said. But even to her ears her voice sounded less than perfectly confident.

3

London, England

“Tea, Ms. Creed?” asked the bluff and jovial old Englishman with the big pink face, a brush of white hair and a red vest straining slightly over his paunch. With an exquisitely manicured hand he held up a white porcelain teapot with flowers painted on it.

Annja smiled. “Thank you, Sir Sidney.” She started to rise from the floral-upholstered chair. She would term the small round table, the flowered sofa and chairs, the eclectic bric-a-brac in Sir Sidney Hazelton’s parlor as fussy Victorian.

He gestured her to stay seated. He poured the tea with a firm if liver-spotted hand protruding from a stiff white cuff with brisk precision, then brought her the cup with a great air of solicitude.

“Thank you,” she said, accepting.

Sir Sidney reseated himself in his overstuffed chair. He’d offered one like it to Annja, insisting that it was more comfortable than the one she chose. She declined, fearing if she sank into it the thing would devour her. She had to admit that despite his bulk he moved with alacrity, including in and out of the treacherously yielding chair.

“Really, isn’t this notion of lost cities or temples more frightfully romantic than realistic?” he asked. “I mean, what with all these satellites and surveillance aircraft and such today.”

Annja pursed her lips. She had some experience with what could be seen from satellites—and also of things that could not. She chose her words carefully.

“It’s a matter of who pays attention to what image,” she said. She told herself she didn’t need any extra complications. “Not everyone who runs across overhead imaging of, say, a lost temple has the knowledge to recognize what they’re looking at. And many of the most skilled image analysts don’t care. They’re looking for military information, or maybe stray nuclear materials. Not ancient ruins. Although some pretty astonishing ruins have been discovered by overhead photography, just in the last couple of decades.”

“So I gather,” Sir Sidney said. “Well, I must say it does a body good to believe there’s still some mystery left in this old world of ours. Quite bracing, actually.”

She raised a brow. “Aren’t you the expert in lost treasures and fabled ruins?”

He smiled. “My dear, the operative word there is fabled. I am, as you know, a cultural anthropologist. Specifically I am a mythologist. I study the phenomena of myths. Particularly pertaining to myths about lost treasures.”

He grinned. “But there’s very little more exciting than the possibility a myth turns out to be true.”

She had to laugh, both at what he said and his very infectious enthusiasm. “That’s how I feel about it.” Usually, she thought. “And there’s a very definite possibility the trail I’m on might lead to a myth being confirmed.”

He waved grandly. “If I can be of any assistance to a lovely young woman such as yourself—”

He paused to pour more tea and stir in plenty of milk.

“I’ve got to thank you again for sharing your time with me,” Annja said.

“Nonsense, nonsense. The pleasure is mine. I am retired, after all. It’s not as if there are abundant claims upon my time these days. My partner of many years died last year. It was quite sudden.”

“I’m sorry,” Annja said.

“Don’t be,” her host replied. “I’m sure you had nothing to do with it, my dear. I can’t say I’ve grown comfortable with it, or ever shall, I fancy. Doubtless I’ve not that long left in which to do so. On the whole I must say I’m rather glad it happened the way it did. So suddenly and all. It saved him the suffering of a long and possibly agonizing decline—saved us both, really. And at our age it’s not as if our own mortality was a tremendous surprise to us. We’ve seen enough old chums put into the ground to have few illusions on that score.”

Annja smiled.

Sir Sidney leaned forward. “Now,” he said, “suppose you tell me this myth you’re trying to pin like a butterfly to reality’s board.”

After a moment’s pause—she didn’t really like thinking of it that way—Annja did. She shared such scanty information as Roux had provided, plus a few not very helpful details from a file he had subsequently e-mailed her.

Sir Sidney sat listening and nodding. Then he smiled and sat back. “The Golden Elephant,” he said ruminatively. “So you’ve reason to believe it’s real?”

Her heart jumped. “You’ve heard of it?”

“Yes,” he said. “Please don’t get your hopes up quite yet. Just let me think a moment, see what I can recall which might prove of use. Do you mind if I smoke my pipe?”

“No,” Annja said. He produced a pipe from an inner pocket, took up tobacco and various arcane tools from a silver tray on the table next to him.

“I’m a little bit puzzled by one aspect of this,” Annja admitted as he lit up. His pipe smoke had a sweet but not cloying smell. Annja had never particularly disliked pipe smoke, unlike cigarette smoke. She hoped the interview wasn’t going to go on too long, though. The parlor was stuffy, with windows closed and heat turned up against the damp autumn London chill. In this closeness even the most agreeable smoke could quickly overwhelm her. “I thought Southeast Asia was mostly Buddhist.”

“Quite,” Sir Sidney said, puffing and nodding.

“Not that I know much about Asian mythology. But I’d associate elephants with the Hindu god Ganesha, rather than anything Buddhist.”

He smiled. Blue-white smoke wreathed his big benign pink features. “Ah, but elephants are most significant beasts in all of Asia,” he said, clearly warming to the role. “Not just big and imposing creatures, but economically important.”

“Really?”

“Just so. It needn’t surprise us too much that the elephant occupies a role in Buddhist symbolism. It symbolizes strength of mind. Buddhists envision what they call the Seven Jewels of Royal Power. These basically constitute the attributes of earthly kingship.

“One of these jewels is the Precious Elephant. It represents a calm, majestic mind. Useful trait in a king, although one honored more in the breach than the observance, as it were.”

“If Asian history is anything like that of Renaissance Europe,” Annja said, “that’s probably an understatement.”

He chortled around the stem of his pipe.

They spoke a while longer. Annja enjoyed the old man’s conversation. But she increasingly felt restless. “Are you remembering any more about the myths regarding our fabulous Golden Elephant?” she asked.

He puffed. “It’s said to have emeralds for eyes.” His own pale blue eyes twinkled. His manner suggested a child telling secrets.

She leaned forward, pulse quickening. “That sounds like my elephant.”

“Don’t put it in your vest pocket yet, my dear,” he said. “I’m not yet dredging up much from the murky depths of my poor old brain. But I recall hints of travelers’ tales. Even reports from a certain scientific expedition from early this—in the twentieth century.”

He shook his head. “I find it most disconcerting to refer to the twentieth century as the last century. It may not strike you so, of course.”

She shrugged. “I don’t think about it too much. It does strike me a little odd sometimes that there are people capable of holding intelligible conversations who were born in the twenty-first century.” She laughed. “I guess that means I’m getting old.”

He guffawed. “Not at all, my dear!” he said. “Not by a long shot. I dare say, I don’t think you’ll ever grow old.”

She looked sharply at him.

“I’m sorry,” he said quickly. “I suppose that could be misconstrued, couldn’t it? I didn’t mean you won’t enjoy a long and happy life. What I meant to convey was that however deeply your years accumulate, I anticipate that your outlook will remain youthful. For that matter, I don’t doubt the years will lie less heavily on you than me in any event. By all appearances you keep yourself far better than ever I did.” He patted himself on the paunch.

Annja looked studiously down into her tea and tried hard not to read her future there.

“Ah, but I see I’ve gone and spoiled your mood. Forgive a clumsy old man’s musings. Profuse apologies, dear child.”

“Not needed,” she said. She smiled. It wasn’t forced. She was a thoughtful person, but had no patience for brooding. “Do you have any suggestions how I can track down this expedition you mentioned?”

His big pink face creased thoughtfully. At last he made a fretful noise and shook his head.

“It eludes me for the moment,” he said. “I’ll see what I can dig up. In the meantime I do have a next step to suggest to you.”

“What’s that?”

“Why, visit that great repository of arcane archaeological knowledge, the British Museum, and see what you can turn up.”

She smiled. “I’ll do that. Thank you so much.”

“It’s nothing. Indeed, almost literally—doubtless you’ve thought of the museum already. It’s right down the lane and across the Tottenham Court Road, you know.”

“Yes. Thank you, Sir Sidney. You’ve encouraged me. Really. If nothing else, I know I’m not the only one with fantasies about an emerald-eyed gold elephant.”

She stood. “Don’t get up, please,” she said. “I can let myself out. You’ve got my card—please call me if you think of anything. With your permission I’ll check back with you in a day or so.”

He beamed. “It would be my pleasure.”

On impulse, she went and kissed him on the forehead. Then, collecting her umbrella from the stand by the door—an antique elephant’s foot, she noted with amusement—she walked out of his flat into the rainy street.

4

About midafternoon Annja pushed herself back from the flat-screen monitor. She stretched, trying to do so as unobtrusively as possible. Her upper back felt as if it had big rocks in it.

She had spent a frustrating afternoon in the Paul Hamlyn Library, flipping through catalogs and skimming through semirandom volumes. She caught a whiff from the digitized pages of British Archaeology for fall 1921, which mentioned the Colquhoun Expedition of 1899 to what was then Siam. But when she tracked down the details, including Colquhoun’s journals and his report to the Explorers’ Club, he made nary a mention of gold elephants. With or without emerald eyes.

She shook her head. Certain needs were asserting themselves. Not least among them the need to be up and moving.

Checking her watch, Annja reckoned she had plenty of time for a turn through the Joseph E. Hotung Gallery, which held the Asian collections, before returning to her labors. She’d try the reading room next, and see if her luck improved.

The library jutted out to flank the main museum entrance from Great Russell Street. She emerged into the great court. It was like a time shift and somewhat jarring. The ceiling was high, translucent white, crisscrossed by what she took for a geodesic pattern of brace work, springing from a stout white cylindrical structure that dominated the center of the space. The cylinder housed the new reading room. The sterile style, which put her in mind of a seventies science-fiction movie, contrasted jarringly with the pseudo-Greek porticoed walls and their Dorian-capitaled pilasters.

The court wasn’t crowded. A few sullen gaggles of schoolchildren in drab uniforms; some tourists snapping enthusiastically with digital cameras were watched by security guards more sullen than the children. She was vaguely surprised photography was allowed.

She concentrated on movement, striding purposefully through milky light filtered from the cloudy sky above. She focused on the sensations of her body in motion, on being in the moment.

A sudden flurry of movement tugged at her peripheral vision. A female figure was walking, strutting more, through the room. Annja got the impression of a rounded, muscle-taut form in a dark blue jacket and knee-length skirt. Black hair jutted out in a kinky cloud behind the woman’s head, bound by an amber band.

Annja had never seen the woman in the flesh. But she had seen plenty of pictures on the Internet. Especially in the wake of her recent China adventure.

“Easy Ngwenya,” she said under her breath. She felt anger start to seethe. She turned to follow.

Without looking back, the young African woman continued through the hall, into the next room, which housed Indian artifacts. She moved purposefully. More, Annja thought, she moved almost with challenge. Her head was up, her broad shoulders back. She was shorter by a head than Annja, who nonetheless found herself pressed to keep pace.

Annja felt uncharacteristically unsure how to proceed. Her rival—she tried to think of her as quarry—could not have gotten her famous twin Sphinx autopistols through the Museum metal detectors, if she had even dared bring them into Britain. Although Annja suspected Easy would have smuggled the guns in. Great respect for the law didn’t seem to be one of her major traits.

So that was advantage Annja. No means known to modern science would detect her sword otherwise. Actually using it, with numerous witnesses and scarcely fewer security cameras everywhere, might prove a bit more problematic.