Полная версия

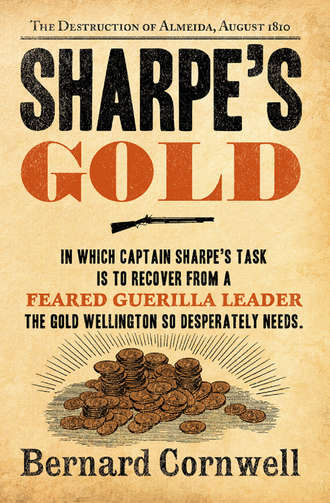

Sharpe’s Gold: The Destruction of Almeida, August 1810

‘I told you! The new man. Marrying Moreno’s daughter.’

‘But why El Católico?’

A stork flapped its way up into the sky, legs back, long wings edged with black, and Kearsey watched it for a second or two.

‘Ah! See what you mean. The Catholic. He prays over his victims before he kills them. The Latin prayer for the dead. Just as a joke, of course.’ The Major sounded gloomy. His fingers riffled the pages as if he were drawing strength from the psalms and stories that were beneath his fingertips. ‘He’s a dangerous man, Sharpe. Ex-officer, knows how to fight, and he doesn’t want us to be involved.’

Sharpe took a deep breath, walked to the battlement, and stared at the rocky northern landscape. ‘So, sir. The gold is a day’s march from here, guarded by Moreno and El Católico, and our job is to fetch it, persuade them to let us take it, and escort it safely over the border.’

‘Quite right.’

‘What’s to stop Moreno already taking it, sir? I mean, while you’re here.’

Kearsey gave a single snorting bark. ‘Thought of that, Sharpe. Left a man there, one of the Regiment, good man. He’s keeping an eye on things, keeping the Partisans sweet.’ Kearsey stood up and, in the growing heat of the sun, shrugged off his cloak. His uniform was blue with a pelisse of silver lace and grey fur. At his side was the polished-steel scabbard of the curved sabre. It was the uniform of the Prince of Wales Dragoons, of Claud Hardy, of Josefina’s lover, Sharpe’s usurper. Kearsey pushed the Bible into his slung sabretache. ‘Moreno trusts us; it’s only El Católico we have to worry about, and he likes Hardy. I think it will be all right.’

‘Hardy?’ Sharpe had somehow sensed it, the feeling of an incomplete story.

‘That’s right.’ Kearsey glanced sharply at the Rifleman. ‘Captain Claud Hardy. You know him?’

‘No, sir.’

Which was true. He had never met him, just watched Josefina walk away to Hardy’s side. He had thought that the rich young cavalry officer was in Lisbon, dancing away the nights, and instead he was here! Waiting a day’s march away. He stared westward, away from Kearsey, at the deep, dark-shadowed gorge of the Coa that slashed across the landscape. Kearsey stamped his feet.

‘Anything else, Sharpe?’

‘No, sir.’

‘Good. We march tonight. Nine o’clock.’

Sharpe turned back. ‘Yes, sir.’

‘One rule, Sharpe. I know the country, you don’t, so no questions, just instant obedience.’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘Company prayers at sunset, unless the Froggies interfere.’

‘Yes, sir.’ Good Lord!

Kearsey returned Sharpe’s salute. ‘Nine o’clock, then. At the north gate!’ He turned and clattered down the winding stairs and Sharpe went back to the battlement, leaned on the granite, and stared unseeing at the huge sprawl of defences beneath him.

Josefina. Hardy. He squeezed the silver ring, engraved with an eagle, which she had bought for him before the battle, but which had been her parting gift when the killing had finished along the banks of the Portina stream north of Talavera. He had tried to forget her, to tell himself she was not worth it, and as he looked up at the rough countryside to the north he tried to force his mind away from her, to think of the gold, of El Católico, the praying killer, and Cesar Moreno. But to do the job with Josefina’s lover? God damn it!

A midshipman, far from the sea, came on to the turret to man the telegraph, and he looked curiously at the tall, darkhaired Rifleman with the scarred face. He looked, the midshipman decided, a dangerous beast, and he watched as a big, tanned hand fidgeted with the hilt of an enormous, straight-bladed sword.

‘She’s a bitch!’ Sharpe said.

‘Pardon, sir?’ The midshipman, fifteen years old, was frightened.

Sharpe turned, unaware he had been joined. ‘Nothing, son, nothing.’ He grinned at the bemused boy. ‘Gold for greed, women for jealousy, and death for the French. Right?’

‘Yes, sir. Of course, sir.’

The boy watched the tall man go down the stairs. Once he had wanted to join the army, years before, but his father had simply looked up and said that anyone who joined the army was stark mad. He started untying the ropes that secured the bladders. His father, as ever, had been undoubtedly right.

CHAPTER FOUR

On foot Kearsey was busy and, to Sharpe’s eyes, ludicrous. He strutted with tiny steps, legs scissoring quickly, while his eyes, above the big, grey moustache, peered acutely at the mass of taller humanity. On horseback, though, astride his huge roan, he was at home as if he had been restored to his true height. Sharpe was impressed by the night’s march. The moon was thin and cloud-ridden, yet the Major led the Company unerringly across difficult country. They crossed the frontier somewhere in the darkness, a grunt from Kearsey announcing the news, and then the route led downhill to the river Agueda, where they waited for the first sign of dawn.

If Kearsey was impressive he was also annoying. The march had been punctuated with advice, condescending advice, as if Kearsey were the only man who understood the problems. He certainly knew the countryside, from the farmlands along the road from Almeida to Ciudad Rodrigo, to the high country that was to the north, the chaos of the valleys and hills that dropped finally to the river Duero, into which the Coa and the Agueda flowed. He knew the villages, the paths, the rivers and where they could be crossed; he knew the high hills and the sheltered passes, and within the lonely countryside he knew the guerrilla bands and where they could be found. Sitting in the mist that ghosted up from the Agueda, he talked, in his gruff voice, about the Partisans. Sharpe and Knowles listened, the unseen river a sound in the background, as the Major talked of ambushes and murders, the secret places where arms were stored, and the signal codes that flashed from hilltop to hilltop.

‘Nothing can move here, Sharpe, nothing, without the Partisans knowing. The French have to escort every messenger with four hundred men. Imagine that? Four hundred sabres to protect one despatch and sometimes even that’s not enough.’

Sharpe could imagine it, and even pity the French for it. Wellington paid hard cash for every captured despatch; sometimes they came to his headquarters with the crusted blood of the dead messenger still crisp on the paper. The messenger who died clean in such a fight was lucky. The wounded were taken not for the information but for revenge, and the war in the hills between French and Spanish was a terrible tale of ghastly pain. Kearsey was riffling the pages of his unseen Bible as he talked.

‘By day the men are shepherds, farmers, millers, but by night they’re killers. For every Frenchman we kill, they kill two. Think what it’s like for the French, Sharpe. Every man, every woman, every child, is an enemy in the countryside. Even the catechism has changed. “Are the French true believers?” “No, they are the devil’s spawn, doing his work, and must be eradicated.”’ He gave his barking laugh.

Knowles stretched his legs. ‘Do the women fight, sir?’

‘They fight, Lieutenant, like the men. Moreno’s daughter, Teresa, is as good as any man. She knows how to ambush, to pursue. I’ve seen her kill.’

Sharpe looked up and saw the mist silvering overhead as the dawn leaked across the hills. ‘Is she the one who’s to marry El Católico?’

Kearsey laughed. ‘Yes.’ He was silent for a second. ‘They’re not all good, of course. Some are just brigands, looting their own people.’ He was silent again. Knowles picked up his uncertainty.

‘Do you mean El Católico, sir?’

‘No.’ Kearsey still seemed uncertain. ‘But he’s a hard man. I’ve seen him skin a Frenchman alive, inch by inch, and praying over him at the same time.’ Knowles made a sound of disgust, but Kearsey, visible now, shook his head. ‘You must understand, Lieutenant, how much they hate. Teresa’s mother was killed by the French and she did not die well.’ He peered down at the Bible, trying to read the print, then looked up at the lightening mist. ‘We must move. Casatejada’s a two-hour march.’ He stood up. ‘You’ll find it best to tie your boots round your neck as we cross the river.’

‘Yes, sir.’ Sharpe said it patiently. He had probably crossed a thousand rivers in his years as a soldier, but Kearsey insisted on treating them all as pure amateurs.

Once over the Agueda, waist-high and cold, they were beyond the farthest British patrols. From now on there was no hope of any friendly cavalry, no Captain Lossow with his German sabres, to help out in trouble. This was French territory, and Kearsey rode ahead, searching the landscape for signs of the enemy. The hills were the French hunting-ground, the scene of countless small and bloody encounters between cavalrymen and Partisans, and Kearsey led the Light Company on paths high up the slopes so that should an enemy patrol appear they could scramble quickly into the high rocks where horsemen could not follow. The Company seemed excited, glad to be near the enemy, and they grinned at Sharpe as he watched them file past on the goat track.

He had only twenty Riflemen now, including himself and Harper, out of the thirty-one survivors he had led from the horror of the retreat to Corunna. They were good men, the Green Jackets, the best in the army, and he was proud of them. Daniel Hagman, the old poacher, who was the best marksman. Parry Jenkins, five feet and four inches of Welsh loquaciousness, who could tease fish out of the most reluctant water. Jenkins, in battle, partnered Isaiah Tongue, educated in books and alcohol, who believed Napoleon was an enlightened genius, England a foul tyranny, but nevertheless fought with the cool deliberation of a good Rifleman. Tongue wrote letters for the other men in the Company, read their infrequent mail when it arrived, and dearly wanted to argue his levelling ideas with Sharpe, but dared not. They were good men.

The other thirty-three were all Redcoats, armed with the smoothbore Brown Bess musket, but they had proved themselves at Talavera and in the tedious winter patrols. Lieutenant Knowles, still awed by Sharpe, but a good officer, decisive and fair. Sharpe nodded at James Kelly, an Irish Corporal, who had stunned the Battalion by marrying Pru Baxter, a widow who was a foot taller and two stones heavier than the skinny Kelly, but the Irishman had hardly stopped smiling in the three months since the marriage. Sergeant Read, the Methodist, who worried about the souls of the Company, and so he should. Most were criminals, avoiding justice by enlisting, and nearly all were drunks, but they were in Sharpe’s Company and he would defend them, even the useless ones like Private Batten or Private Roach, who pimped his wife for a shilling a time.

Sergeant Harper, the best of them all, moved alongside Sharpe. Next to the seven-barrelled gun he had slung two packs belonging to men who were falling with tiredness after the night’s march. He nodded ahead. ‘What’s next, sir?’

‘We pick up the gold and come back. Simple.’

Harper grinned. In battle he was savage, crooning the old stories of the Gaelic heroes, the warriors of Ireland, but away from the fighting he covered his intelligence with a charm that would have fooled the devil. ‘You believe that, sir?’

Sharpe had no time to reply. Kearsey had stopped, two hundred yards ahead, and dismounted. He pointed left, up the slope, and Sharpe repeated the gesture. The Company moved quickly into the stones and crouched while Sharpe, still puzzled, ran towards the Major. ‘Sir?’

Kearsey did not reply. The Major was alert, like a dog pointing at game, but Sharpe could see from his eyes that Kearsey was not sure what had alarmed him. Instinct, the soldier’s best gift, was working, and Sharpe, who trusted his own instinct, could sense nothing. ‘Sir?’

The Major nodded at a hilltop, half a mile away. ‘See the stones?’

Sharpe could see a heap of boulders on the peak of the hill. ‘Yes, sir.’

‘There’s a white stone showing, yes?’ Sharpe nodded, and Kearsey seemed relieved that his eyes had not deceived him. ‘That means the enemy are abroad. Come on.’

The Major led his horse, Marlborough, into the tangle of rocks, and Sharpe followed patiently, wondering how many other secret signs they had passed in the night. The Company were curious, but silent, and Kearsey led them over the crest, into a rock-strewn valley, and then eastwards again, back on course for the village where the gold should be waiting.

‘They won’t be up here, Sharpe.’ The Major sounded certain.

‘Where, then?’

Kearsey nodded ahead, past the head of the valley. He looked worried. ‘Casatejada.’

To the north, over the hilltops, a bank of cloud was ominous and still on the horizon, but otherwise the sky was arching an untouched blue over the pale grass and rocks. To Sharpe’s eyes there was nothing strange in the landscape. A rock thrush, startled and noisy, flew from the Company’s path, and Sharpe saw Harper smile with enjoyment. The Sergeant could have spent his life watching birds, but he gave the thrush only a few seconds’ attention before searching the skyline again. Everything seemed innocent, a high valley in morning sunshine, yet the whole Company was alert because of the Major’s sudden knowledge.

A mile up the valley, as the sides began to flatten out into a bleak hilltop, Kearsey tethered Marlborough to a rock. He talked to the horse and Sharpe knew that on many lonely days, behind French lines, the small Major would have only the big, intelligent roan for company. The Major turned back to Sharpe, the gruffness back in his voice. ‘Come on. Keep low.’

The skyline proved to be a false crest. Beyond was a gully, shaped like a bowl, and as Sharpe ran over the lip he realized that Kearsey had brought them to a vantage point high in the hills that was overlooked only by the peak with its white, warning stone. It was a steep scramble over the edge, impossible for a horse, and the Company tumbled into the bowl and sat, grateful for the rest, as Kearsey beckoned Sharpe to the far side. ‘Keep low!’ The two officers used hands and feet to climb the bowl’s inner face and then they were peering over the edge. ‘Casatejada.’ Kearsey spoke almost grudgingly, as if not wanting to share this high and secret village with another Englishman.

Casatejada was beautiful: a small village in a high valley that was built where two streams met and irrigated enough land to keep forty or so houses filled with food. Sharpe began to memorize the layout of the village, two miles away, from the old fortress-tower at one end of the main street, a reminder that this was border country, past the church, to the one large house at the far end of the street. He dared not use his telescope, pointing it eastwards towards the rising sun that might flash on the lens, but even without it, he could see that the house was built round a lavish courtyard and that within its outer walls were stables and outbuildings. He asked Kearsey about the house.

‘Moreno’s house, Sharpe.’

‘He’s rich?’

Kearsey shrugged. ‘Used to be. The family own the whole valley and a lot of other land. But who’s rich with the French here?’ Kearsey’s eyes flicked left, down the street. ‘The castillo. Ruins now, but they used to take refuge there from the raids over the hills.’

There were no animals in sight, no humans, just the wind stirring the barley that should have been harvested. The single village street was empty and Sharpe let his eyes travel beyond the church, across a flat pasture to some stunted fruit trees, and there, half hidden by the orchard, was another church and a bell-tower.

‘What’s the far church?’

‘Hermitage.’

‘Hermitage?’

Kearsey grunted. ‘Some holy man lived there, long ago, and they built the shrine. It’s not used now, except that the graveyard’s there.’ Sharpe could see the walled cemetery through the trees. Kearsey nodded at the hermitage. ‘That’s where the gold is.’

‘Where’s it hidden?’

‘In the Moreno vault, inside the hermitage.’

The village street ran left and right across Sharpe’s vision. To the right, to the south, the street became a road that disappeared in the purple shadows at the far end of the valley, miles away, but to the left the road came nearer to the hills before disappearing into the slopes. He pointed.

‘Where does it go?’

‘Ford at San Anton.’ Kearsey was chewing his grey moustache, glancing up at the white stone on the hilltop, back to the village. ‘They must be there.’

‘Who?’

‘The French.’

Nothing moved, except the wind on the heavy barley. Kearsey’s eyes flicked up and down the valley. ‘An ambush.’

‘What do you mean, sir?’ Sharpe was beginning to understand that in this kind of warfare he knew nothing.

Kearsey spoke quietly. ‘The weathervane on the church. It’s moving. When the Partisans are in the village they jam it with a metal rod so you know they’re there. There are no animals. The French have butchered them for food. They’re waiting, Sharpe, in the village, and they want the Partisans to think they’ve gone.’

‘Will they?’

Kearsey gave his asthmatic bark. ‘No. They’re too clever. The French can wait all day.’

‘And us, sir?’

Kearsey flashed one of his fierce glances on Sharpe. ‘We wait, too.’

The men had piled their arms on the floor of the bowl, and as the sun rose they used the weapons to support spread greatcoats to give themselves shade. The water in the canteens was brackish but drinkable, and the Company grumbled because, before leaving Almeida, Sharpe, Harper and Knowles had virtually stripped each man and taken away twelve bottles of wine and two of rum. Even so, Sharpe knew, someone would have drink, but not enough to do any harm. The sun’s heat increased, baking the rocks, while most of the Company slept, heads pillowed on haversacks, and single sentries watched the empty landscape around the hidden gully. Sharpe was frustrated. He could climb the gully’s rim, see where the gold was stored, see where the survival of the army was hidden in a seemingly uninhabited valley, yet he could do nothing. As midday approached he slept.

‘Sir!’ Harper was shaking him. ‘We’ve got action.’

He had slept no more than fifteen minutes. ‘Action?’

‘In the valley, sir.’

The Company were stirring, looking eagerly at Sharpe, but he waved them down. They must stifle their curiosity and watch, instead, as Sharpe and Harper climbed up beside Kearsey and Knowles on the rock rim. Kearsey was grinning. ‘Watch this.’

From the north, from a track that led down from high pastures, five horsemen trotted slowly towards the village. Kearsey had his telescope extended and Sharpe found his own. ‘Partisans, sir?’

Kearsey nodded. ‘Three of them.’

Sharpe pulled out his glass, his fingers feeling the inset brass plate, and found the small group of horsemen. The Spaniards rode, straight-backed and easy, looking relaxed and comfortable, but their two companions were quite different. Naked men, tied to the saddles, and through the glass Sharpe could see their heads jerking with fear as they wondered what was to happen to them.

‘Prisoners.’ Kearsey said the word fiercely.

‘What’s going to happen?’ Knowles was fidgeting.

‘Wait.’ Kearsey was still grinning.

Nothing stirred in the village. If the French were there they were well hidden. Kearsey chuckled. ‘The ambushers ambushed!’

The horsemen had stopped. Sharpe swung the glass back. One Spaniard held the reins of the prisoners’ horses while the others dismounted. The naked men were pulled from their saddles and the ropes that had tied their legs beneath the horses’ bellies were used to lash their ankles tightly together. Then more rope was produced, thick loops hanging from the Partisans’ saddles, and the two Frenchmen were tied behind the horses. Knowles had borrowed Sharpe’s telescope and beneath his tan he paled, shocked by the sight.

‘They won’t run far,’ the Lieutenant said half in hope.

Kearsey shook his head. ‘They will.’

Sharpe took the glass back. The Partisans were unfastening their saddle-bags, going back to the horses with the roped men. ‘What are they doing, sir?’

‘Thistles.’

Sharpe understood. Along the paths and in the high rocks huge purple thistles grew, often as high as a man, and the Spanish, a horse at a time, were thrusting the heads of the spiny plants beneath the empty saddles. The first horse began fighting, rearing up, but was held firm, until with a final crack over its rump the beast was released and it sprung off, infuriated by the pain, the prisoner jerked by the legs and scraped in a cloud of dust behind the angry horse.

The second horse followed, pulling left and right, zigzagging behind the first towards the village. The three Spaniards mounted and stood their horses quietly. One had a long cigar, and through the telescope Sharpe saw the smoke drift over the fields.

‘Good God.’ Knowles stared unbelieving.

‘No need for blasphemy.’ Kearsey’s gruff reprimand did not hide the excitement in his voice.

The two naked, tied men were invisible in the dust, but, as the horses swerved at a rock, Sharpe caught a glimpse, a flash through the cloud, of a body streaked red, and then the horse was running again. By now the Frenchmen would be unconscious, the pain gone, but the Partisans had guessed right and Sharpe saw the first movement in the village as the gates of Cesar Moreno’s big house were thrown open and cavalry, hidden all morning, rode on to the street. Sharpe saw sky-blue trousers, brown jackets, and the tall fur helmet. ‘Hussars.’

‘Wait. This is the clever bit.’ Kearsey could not hide his admiration.

The Hussars, sabres drawn, cantered down the street to meet the two horses with their terrible attachments. It seemed that the Spanish plan was to end in anticlimax, for the Hussars would rescue the two bloody and battered Frenchmen at the northern end of the village, but then the two horses became aware of the cavalry. They stopped.

‘Jesus,’ Harper muttered. He was using Sharpe’s glass. ‘One of those buggers is moving.’

Sharpe could see him. Far from unconscious, one of the two naked Frenchmen was trying to sit up, a writhing mass of blood, but suddenly he was whirled back to the roadway, wrenched terribly about, and the horses were moving, away from the Hussars, splitting apart in a mad, panicked gallop. Kearsey nodded in satisfaction. ‘They won’t go near French cavalry, not unless they’re ridden. They’re too used to running from it.’

There was chaos in the valley. The horses, with their thistle-driven pain, circled crazily in the fields; the Hussars, all order gone, tried to ride them down, and the nearer the French came to them the more the Spanish horses took the disorganized mass northwards. Sharpe guessed there were a hundred Frenchmen, in undisciplined groups, crossing and recrossing the fields. He looked back to the village, saw more horsemen standing in the street, watching the chase, and he wondered how he would feel if those two bodies were his men, and he knew that he would do what the French were doing: try to rescue them.

‘Good.’ Knowles seemed to have sided, instinctively, with the French.

One of the horses had been caught and quieted, and dismounted French cavalrymen were unbuckling the girth and untying the prisoner. A trumpet sounded, calling order to the scattered Hussars who still raced after the other horse, and at that exact moment, as the trumpet notes reached the gully, El Católico launched his own horsemen from the northern hills. They came down on to the scattered and outnumbered French in a long line, blacks and browns and greys, swords of all descriptions held over their heads, the dust spurting behind them, while from the rocks on the hillside Sharpe saw muskets firing over their heads at the surprised French.

Kearsey almost jumped over the rim with joy. His fist slammed into the rock. ‘Perfect!’