Полная версия

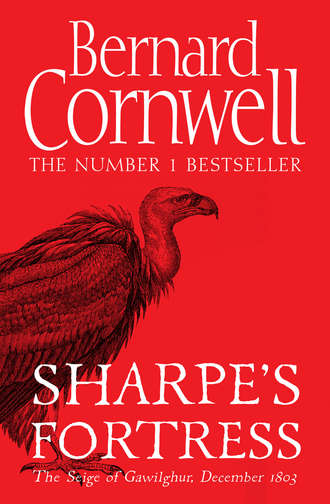

Sharpe’s Fortress: The Siege of Gawilghur, December 1803

‘Like ninepins.’ Ensign Venables had appeared at Sharpe’s side. Roderick Venables was sixteen years old and attached to number seven company. He had been the battalion’s most junior officer till Sharpe joined, and Venables had taken it on himself to be a tutor to Sharpe in how officers should behave. ‘They’re bowling us over like ninepins, eh, Richard?’

Before Sharpe could reply a half-dozen men of number six company threw themselves aside as a cannonball bounced hard and low towards them. It whipped harmlessly through the gap they had made. The men laughed at having evaded it, then Sergeant Colquhoun ordered them back into their two ranks.

‘Aren’t you supposed to be on the left of your company?’ Sharpe asked Venables.

‘You’re still thinking like a sergeant, Richard,’ Venables said. ‘Pig-ears doesn’t mind where I am.’ Pig-ears was Captain Lomax, who had earned his nickname not because of any peculiarity about his ears, but because he had a passion for crisply fried pig-ears. Lomax was easy-going, unlike Urquhart who liked everything done strictly according to regulations. ‘Besides,’ Venables went on, ‘there’s damn all to do. The lads know their business.’

‘Waste of time being an ensign,’ Sharpe said.

‘Nonsense! An ensign is merely a colonel in the making,’ Venables said. ‘Our duty, Richard, is to be decorative and stay alive long enough to be promoted. But no one expects us to be useful! Good God! A junior officer being useful? That’ll be the day.’ Venables gave a hoot of laughter. He was a bumptious, vain youth, but one of the few officers in the 74th who offered Sharpe companionship. ‘Did you hear a new draft has come to Madras?’ he asked.

‘Urquhart told me.’

‘Fresh men. New officers. You won’t be junior any more.’

Sharpe shook his head. ‘Depends on the date the new men were commissioned, doesn’t it?’

‘Suppose it does. Quite right. And they must have sailed from Britain long before you got the jump up, eh? So you’ll still be the mess baby. Bad luck, old fellow.’

Old fellow? Quite right, Sharpe thought. He was old. Probably ten years older than Venables, though Sharpe was not exactly sure for no one had ever bothered to note down his birth date. Ensigns were youths and Sharpe was a man.

‘Whoah!’ Venables shouted in delight and Sharpe looked up to see that a round shot had struck the edge of an irrigation canal and bounced vertically upwards in a shower of soil. ‘Pig-ears says he once saw two cannonballs collide in mid-air,’ Venables said. ‘Well, he didn’t actually see it, of course, but he heard it. He says they suddenly appeared in the sky. Bang! Then flopped down.’

‘They’d have shattered and broken up,’ Sharpe said.

‘Not according to Pig-ears,’ Venables insisted. ‘He says they flattened each other.’ A shell exploded ahead of the company, whistling scraps of iron casing overhead. No one was hurt and the files stepped round the smoking fragments. Venables stooped and plucked up a scrap, juggling it because of the heat. ‘Like to have keepsakes,’ he explained, slipping the piece of iron into a pouch. ‘I’ll send it home for my sisters. Why don’t our guns stop and fire?’

‘Still too far away,’ Sharpe said. The advancing line still had half a mile to go and, while the six-pounders could fire at that distance, the gunners must have decided to get really close so that their shots could not miss. Get close, that was what Colonel McCandless had always told Sharpe. It was the secret of battle. Get close before you start slaughtering.

A round shot struck a file in seven company. It was on its first graze, still travelling at blistering speed, and the two men of the file were whipped backwards in a spray of mingling blood. ‘Jesus,’ Venables said in awe. ‘Jesus!’ The corpses were mixed together, a jumble of splintered bones, tangled entrails and broken weapons. A corporal, one of the file-closers, stooped to extricate the men’s pouches and haversacks from the scattered offal. ‘Two more names in the church porch,’ Venables remarked. ‘Who were they, Corporal?’

‘The McFadden brothers, sir.’ The Corporal had to shout to be heard over the roar of the Mahratta guns.

‘Poor bastards,’ Venables said. ‘Still, there are six more. A fecund lady, Rosie McFadden.’

Sharpe wondered what fecund meant, then decided he could guess. Venables, for all his air of carelessness, was looking slightly pale as though the sight of the churned corpses had sickened him. This was his first battle, for he had been sick with the Malabar Itch during Assaye, but the Ensign was forever explaining that he could not be upset by the sight of blood because, from his earliest days, he had assisted his father who was an Edinburgh surgeon, but now he suddenly turned aside, bent over and vomited. Sharpe kept stolidly walking. Some of the men turned at the sound of Venables’s retching.

‘Eyes front!’ Sharpe snarled.

Sergeant Colquhoun gave Sharpe a resentful look. The Sergeant believed that any order that did not come from himself or from Captain Urquhart was an unnecessary order.

Venables caught up with Sharpe. ‘Something I ate.’

‘India does that,’ Sharpe said sympathetically.

‘Not to you.’

‘Not yet,’ Sharpe said and wished he was carrying a musket so he could touch the wooden stock for luck.

Captain Urquhart sheered his horse leftwards. ‘To your company, Mister Venables.’

Venables scuttled away and Urquhart rode back to the company’s right flank without acknowledging Sharpe’s presence. Major Swinton, who commanded the battalion while Colonel Wallace had responsibility for the brigade, galloped his horse behind the ranks. The hooves thudded heavily on the dry earth. ‘All well?’ Swinton called to Urquhart.

‘All well.’

‘Good man!’ Swinton spurred on.

The sound of the enemy guns was constant now, like thunder that did not end. A thunder that pummelled the ears and almost drowned out the skirl of the pipers. Earth fountained where round shot struck. Sharpe, glancing to his left, could see a scatter of bodies lying in the wake of the long line. There was a village there. How the hell had he walked straight past a village without even seeing it? It was not much of a place, just a huddle of reed-thatched hovels with a few patchwork gardens protected by cactus-thorn hedges, but he had still walked clean past without noticing its existence. He could see no one there. The villagers had too much sense. They would have packed their few pots and pans and buggered off as soon as the first soldier appeared near their fields. A Mahratta round shot smacked into one of the hovels, scattering reed and dry timber, and leaving the sad roof sagging.

Sharpe looked the other way and saw enemy cavalry advancing in the distance, then he glimpsed the blue and yellow uniforms of the British 19th Dragoons trotting to meet them. The late-afternoon sunlight glittered on drawn sabres. He thought he heard a trumpet call, but maybe he imagined it over the hammering of the guns. The horsemen vanished behind a stand of trees. A cannonball screamed overhead, a shell exploded to his left, then the 74th’s Light Company edged inwards to give an ox team room to pass back southwards. The British cannon had been dragged well ahead of the attacking line where they had now been turned and deployed. Gunners rammed home shot, pushed priming quills into touch-holes, stood back. The sound of the guns crashed across the field, blotting the immediate view with grey-white smoke and filling the air with the nauseous stench of rotted eggs.

The drummers beat on, timing the long march north. For the moment it was a battle of artillerymen, the puny British six-pounders firing into the smoke cloud where the bigger Mahratta guns pounded at the advancing redcoats. Sweat trickled down Sharpe’s belly, it stung his eyes and it dripped from his nose. Flies buzzed by his face. He pulled the sabre free and found that its handle was slippery with perspiration, so he wiped it and his right hand on the hem of his red coat. Suddenly he badly wanted to piss, but this was not the time to stop and unbutton breeches. Hold it, he told himself, till the bastards are beaten. Or piss in your pants, he told himself, because in this heat no one would know it from sweat and it would dry quickly enough. Might smell, though. Better to wait. And if any of the men knew he had pissed his pants he would never live it down. Pisspants Sharpe. A ball thumped overhead, so close that its passage rocked Sharpe’s shako. A fragment of something whirred to his left. A man was on the ground, vomiting blood. A dog barked as another tugged blue guts from an opened belly. The beast had both paws on the corpse to give its tug purchase. A file-closer kicked the dog away, but as soon as the man was gone the dog ran back to the body. Sharpe wished he could have a good wash. He knew he was lousy, but then everyone was lousy. Even General Wellesley was probably lousy. Sharpe looked eastwards and saw the General spurring up behind the kilted 78th. Sharpe had been Wellesley’s orderly at Assaye and as a result he knew all the staff officers who rode behind the General. They had been much friendlier than the 74th’s officers, but then they had not been expected to treat Sharpe as an equal.

Bugger it, he thought. Maybe he should take Urquhart’s advice. Go home, take the cash, buy an inn and hang the sabre over the serving hatch. Would Simone Joubert go to England with him? She might like running an inn. The Buggered Dream, he could call it, and he would charge army officers twice the real price for any drink.

The Mahratta guns suddenly went silent, at least those that were directly ahead of the 74th, and the change in the battle’s noise made Sharpe peer ahead into the smoke cloud that hung over the crest just a quarter-mile away. More smoke wreathed the 74th, but that was from the British guns. The enemy gun smoke was clearing, carried northwards on the small wind, but there was nothing there to show why the guns at the centre of the Mahratta line had ceased fire. Perhaps the buggers had run out of ammunition. Some hope, he thought, some bloody hope. Or perhaps they were all reloading with canister to give the approaching redcoats a rajah’s welcome.

God, but he needed a piss and so he stopped, tucked the sabre into his armpit, then fumbled with his buttons. One came away. He swore, stooped to pick it up, then stood and emptied his bladder onto the dry ground. Then Urquhart was wheeling his horse. ‘Must you do that now, Mister Sharpe?’ he asked irritably.

Yes, sir, three bladders full, sir, and damn your bloody eyes, sir. ‘Sorry, sir,’ Sharpe said instead. So maybe proper officers didn’t piss? He sensed the company was laughing at him and he ran to catch up, fiddling with his buttons. Still there was no gunfire from the Mahratta centre. Why not? But then a cannon on one of the enemy flanks fired slantwise across the field and the ball grazed right through number six company, ripping a front rank man’s feet off and slashing a man behind through the knees. Another soldier was limping, his leg deeply pierced by a splinter from his neighbour’s bone. Corporal McCallum, one of the file-closers, tugged men into the gap while a piper ran across to bandage the wounded men. The injured would be left where they fell until after the battle when, if they still lived, they would be carried to the surgeons. And if they survived the knives and saws they would be shipped home, good for nothing except to be a burden on the parish. Or maybe the Scots did not have parishes; Sharpe was not sure, but he was certain the buggers had workhouses. Everyone had workhouses and paupers’ graveyards. Better to be buried out here in the black earth of enemy India than condemned to the charity of a workhouse.

Then he saw why the guns in the centre of the Mahratta line had ceased fire. The gaps between the guns were suddenly filled with men running forward. Men in long robes and headdresses. They streamed between the gaps, then joined together ahead of the guns beneath long green banners that trailed from silver-topped poles. Arabs, Sharpe thought. He had seen some at Ahmednuggur, but most of those had been dead. He remembered Sevajee, the Mahratta who fought alongside Colonel McCandless, saying that the Arab mercenaries were the best of all the enemy troops.

Now there was a horde of desert warriors coming straight for the 74th and their kilted neighbours.

The Arabs came in a loose formation. Their guns had decorated stocks that glinted in the sunlight, while curved swords were scabbarded at their waists. They came almost jauntily, as though they had utter confidence in their ability. How many were there? A thousand? Sharpe reckoned at least a thousand. Their officers were on horseback. They did not advance in ranks and files, but in a mass, and some, the bravest men, ran ahead as if eager to start the killing. The great robed mass was chanting a shrill war cry, while in its centre drummers were beating huge instruments that pulsed a belly-thumping beat across the field. Sharpe watched the nearest British gun load with canister. The green banners were being waved from side to side so that the silk trails snaked over the warriors’ heads. Something was written on the banners, but it was in no script that Sharpe recognized.

‘74th!’ Major Swinton called. ‘Halt!’

The 78th had also halted. The two Highland battalions, both under strength after their losses at Assaye, were taking the full brunt of the Arab charge. The rest of the battlefield seemed to melt away. All Sharpe could see was the robed men coming so eagerly towards him.

‘Make ready!’ Swinton called.

‘Make ready!’ Urquhart echoed.

‘Make ready!’ Sergeant Colquhoun shouted. The men raised their muskets chest high and pulled back the heavy hammers.

Sharpe pushed into the gap between number six company and its left-hand neighbour, number seven. He wished he had a musket. The sabre felt flimsy.

‘Present!’ Swinton called.

‘Present!’ Colquhoun echoed, and the muskets went into the men’s shoulders. Heads bowed to peer down the barrels’ lengths.

‘You’ll fire low, boys,’ Urquhart said from behind the line, ‘you’ll fire low. To your place, Mister Sharpe.’

Bugger it, Sharpe thought, another bloody mistake. He stepped back behind the company where he was supposed to make sure no one tried to run.

The Arabs were close. Less than a hundred paces to go now. Some had their swords drawn. The air, miraculously smoke-free, was filled with their blood-chilling war cry which was a weird ululating sound. Not far now, not far at all. The Scotsmen’s muskets were angled slightly down. The kick drove the barrels upwards, and untrained troops, not ready for the heavy recoil, usually fired high. But this volley would be lethal.

‘Wait, boys, wait,’ Pig-ears called to number seven company. Ensign Venables slashed at weeds with his claymore. He looked nervous.

Urquhart had drawn a pistol. He dragged the cock back, and his horse’s ears flicked back as the pistol’s spring clicked.

Arab faces screamed hatred. Their great drums were thumping. The redcoat line, just two ranks deep, looked frail in front of the savage charge.

Major Swinton took a deep breath. Sharpe edged towards the gap again. Bugger it, he wanted to be in the front line where he could kill. It was too nerve-racking behind the line.

‘74th!’ Swinton shouted, then he paused. Men’s fingers curled about their triggers.

Let them get close, Swinton was thinking, let them get close.

Then kill them.

Prince Manu Bappoo’s brother, the Rajah of Berar, was not at the village of Argaum where the Lions of Allah now charged to destroy the heart of the British attack. The Rajah did not like battle. He liked the idea of conquest, he loved to see prisoners paraded and he craved the loot that filled his storehouses, but he had no belly for fighting.

Manu Bappoo had no such qualms. He was thirty-five years old, he had fought since he was fifteen, and all he asked was the chance to go on fighting for another twenty or forty years. He considered himself a true Mahratta; a pirate, a rogue, a thief in armour, a looter, a pestilence, a successor to the generations of Mahrattas who had dominated western India by pouring from their hill fastnesses to terrorize the plump princedoms and luxurious kingdoms in the plains. A quick sword, a fast horse and a wealthy victim, what more could a man want? And so Bappoo had ridden deep and far to bring plunder and ransom back to the small land of Berar.

But now all the Mahratta lands were threatened. One British army was conquering their northern territory, and another was here in the south. It was this southern redcoat force that had broken the troops of Scindia and Berar at Assaye, and the Rajah of Berar had summoned his brother to bring his Lions of Allah to claw and kill the invader. This was not a task for horsemen, the Rajah had warned Bappoo, but for infantry. It was a task for the Arabs.

But Bappoo knew this was a task for horsemen. His Arabs would win, of that he was sure, but they could only break the enemy on the immediate battlefield. He had thought to let the British advance right up to his cannon, then release the Arabs, but a whim, an intimation of triumph, had decided him to advance the Arabs beyond the guns. Let the Lions of Allah loose on the enemy’s centre and, when that centre was broken, the rest of the British line would scatter and run in panic, and that was when the Mahratta horsemen would have their slaughter. It was already early evening, and the sun was sinking in the reddened west, but the sky was cloudless and Bappoo was anticipating the joys of a moonlit hunt across the flat Deccan Plain. ‘We shall gallop through blood,’ he said aloud, then led his aides towards his army’s right flank so that he could charge past his Arabs when they had finished their fight. He would let his victorious Lions of Allah pillage the enemy’s camp while he led his horsemen on a wild victorious gallop through the moon-touched darkness.

And the British would run. They would run like goats from the tiger. But the tiger was clever. He had only kept a small number of horsemen with the army, a mere fifteen thousand, while the greater part of his cavalry had been sent southwards to raid the enemy’s long supply roads. The British would flee straight into those men’s sabres.

Bappoo trotted his horse just behind the right flank of the Lions of Allah. The British guns were firing canister and Bappoo saw how the ground beside his Arabs was being flecked by the blasts of shot, and he saw the robed men fall, but he saw how the others did not hesitate, but hurried on towards the pitifully thin line of redcoats. The Arabs were screaming defiance, the guns were hammering, and Bappoo’s soul soared with the music. There was nothing finer in life, he thought, than this sensation of imminent victory. It was like a drug that fired the mind with noble visions.

He might have spared a moment’s thought and wondered why the British did not use their muskets. They were holding their fire, waiting until every shot could kill, but the Prince was not worrying about such trifles. In his dreams he was scattering a broken army, slashing at them with his tulwar, carving a bloody path south. A fast sword, a quick horse and a broken enemy. It was the Mahratta paradise, and the Lions of Allah were opening its gates so that this night Manu Bappoo, Prince, warrior and dreamer, could ride into legend.

CHAPTER TWO

‘Fire!’ Swinton shouted.

The two Highland regiments fired together, close to a thousand muskets flaming to make an instant hedge of thick smoke in front of the battalions. The Arabs vanished behind the smoke as the redcoats reloaded. Men bit into the grease-coated cartridges, tugged ramrods that they whirled in the air before rattling them down into the barrels. The churning smoke began to thin, revealing small fires where the musket wadding burned in the dry grass.

‘Platoon fire!’ Major Swinton shouted. ‘From the flanks!’

‘Light Company!’ Captain Peters called on the left flank. ‘First platoon, fire!’

‘Kill them! Your mothers are watching!’ Colonel Harness shouted. The Colonel of the 78th was mad as a hatter and half delirious with a fever, but he had insisted on advancing behind his kilted Highlanders. He was being carried in a palanquin and, as the platoon fire began, he struggled from the litter to join the battle, his only weapon a broken riding crop. He had been recently bled, and a stained bandage trailed from a coat sleeve. ‘Give them a flogging, you dogs! Give them a flogging.’

The two battalions fired in half companies now, each half company firing two or three seconds after the neighbouring platoon so that the volleys rolled in from the outer wings of each battalion, met in the centre and then started again at the flanks. Clockwork fire, Sharpe called it, and it was the result of hours of tedious practice. Beyond the battalions’ flanks the six-pounders bucked back with each shot, their wheels jarring up from the turf as the canisters ripped apart at the muzzles. Wide swathes of burning grass lay under the cannon smoke. The gunners were working in shirtsleeves, swabbing, ramming, then ducking aside as the guns pitched back again. Only the gun commanders, most of them sergeants, seemed to look at the enemy, and then only when they were checking the alignment of the cannon. The other gunners fetched shot and powder, sometimes heaved on a handspike or pushed on the wheels as the gun was relaid, then swabbed and loaded again. ‘Water!’ a corporal shouted, holding up a bucket to show that the swabbing water was gone.

‘Fire low! Don’t waste your powder!’ Major Swinton called as he pushed his horse into the gap between the centre companies. He peered at the enemy through the smoke. Behind him, next to the 74th’s twin flags, General Wellesley and his aides also stared at the Arabs beyond the smoke clouds. Colonel Wallace, the brigade commander, trotted his horse to the battalion’s flank. He called something to Sharpe as he went by, but his words were lost in the welter of gunfire, then his horse half spun as a bullet struck its haunch. Wallace steadied the beast, looked back at the wound, but the horse did not seem badly hurt. Colonel Harness was thrashing one of the native palanquin bearers who had been trying to push the Colonel back into the curtained vehicle. One of Wellesley’s aides rode back to quieten the Colonel and to persuade him to go southwards.

‘Steady now!’ Sergeant Colquhoun shouted. ‘Aim low!’

The Arab charge had been checked, but not defeated. The first volley must have hit the attackers cruelly hard for Sharpe could see a line of bodies lying on the turf. The bodies looked red and white, blood against robes, but behind that twitching heap the Arabs were firing back to make their own ragged cloud of musket smoke. They fired haphazardly, untrained in platoon volleys, but they reloaded swiftly and their bullets were striking home. Sharpe heard the butcher’s sound of metal hitting meat, saw men hurled backwards, saw some fall. The file-closers hauled the dead out of the line and tugged the living closer together. ‘Close up! Close up!’ The pipes played on, adding their defiant music to the noise of the guns. Private Hollister was hit in the head and Sharpe saw a cloud of white flour drift away from the man’s powdered hair as his hat fell off. Then blood soaked the whitened hair and Hollister fell back with glassy eyes.

‘One platoon, fire!’ Sergeant Colquhoun shouted. He was so short-sighted that he could barely see the enemy, but it hardly mattered. No one could see much in the smoke, and all that was needed was a steady nerve and Colquhoun was not a man to panic.

‘Two platoon, fire!’ Urquhart shouted.

‘Christ Jesus!’ a man called close to Sharpe. He reeled backwards, his musket falling, then he twisted and dropped to his knees. ‘Oh God, oh God, oh God,’ he moaned, clutching at his throat. Sharpe could see no wound there, but then he saw blood seeping down the man’s grey trousers. The dying man looked up at Sharpe, tears showed at his eyes, then he pitched forward.