Полная версия

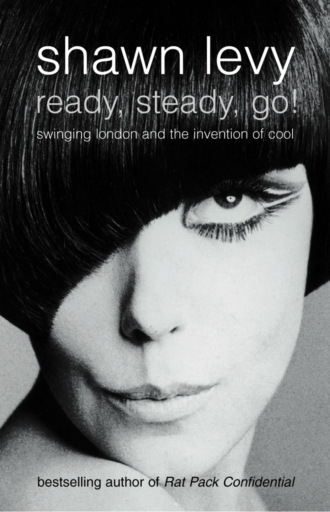

Ready, Steady, Go!: Swinging London and the Invention of Cool

A few weeks later, Bailey requested her for one of his first Vogue jobs.

‘I’m Bailey,’ he told her by way of introduction.

‘Just Bailey?’

‘Just Bailey.’

And that would be all she’d ever call him.

Shrimpton was taller than Bailey – even with his Cuban heels; she knew he was married; and she was still living in the country with her parents. Still, she confessed, ‘We were instantly attracted to each other. Whenever we worked together this attraction created a strong sexual atmosphere.’

Over the coming few months, they would inch closer and closer to acting on that attraction. In that time, Bailey taught her how to dress and how to model, but he never tried to make her into something she was not. Rather, relying on the aesthetic he was developing in his life and in his photography, he encouraged her naturalness. ‘She took modelling with a bit of dignity,’ Bailey said. ‘Honestly, I don’t think she really cared if she did it or not.’

But the results, he said, were almost always the sort he was after: With Jean you never had to reshoot anything. Ever. She was always in perfect synch with the camera. It’s funny, though; in terms of personal style, Jean didn’t have any. She just dressed in any old rags. Most of the time she looked like a bag lady.’

She concurred with his assessment of her attitude towards the business of fashion: ‘Modelling meant little to me till I met him,’ she said when she became famous. ‘I was just lucky getting work. Bailey has been the greatest influence in my life so far. He says when I met him I was a county chick. All MGs and Daddy and chinless wonders.’ And she defined the look that he and she had cultivated as ‘not beatnik and not classical either – but more beatnik than classical’.

Their technique when they worked together was remarkably simple: ‘We would just drive out to the country with some clothes,’ according to Bailey, ‘and Jean did her own hair and make-up.’ Vogue editors were initially ambivalent towards the off-the-cuff feel of the stuff he was giving them, referring to the results as ‘Old Bailey and his scruffy look’. But Bailey was perfecting his theory about how to shoot fashion: ‘If you look at my fashion pictures, there’s a personality to the girls. The girl is always the most important, then the dress. If she’s not looking stunning, then I figure the dress doesn’t, either. The girl is the catalyst that brings it all together.’ And when they saw what he managed with his new model, the editors couldn’t deny that Bailey had discovered a star; their work together became a sensation. Shrimpton – at first anonymous but soon heralded as ‘the Shrimp’ – was becoming a pin-up darling throughout the country.

Shrimpton was a sensation not only because of her fabulous looks or the extraordinary photos Bailey took of her. The two would eventually become famous – infamous even – for their lives together. Despite the obvious obstacles to a romance, Bailey courted Shrimpton as diligently as had the lovesick public school suitors she was accustomed to – with his own personal twist. He would take her out to dinner, not to chic West End restaurants but rather to a favourite chop suey joint on East Ham High Street. With their late working hours and their increasingly common socialising, Shrimpton wasn’t always able to go all the way home at night, and she stayed once or twice at Bailey’s parents’ home – where she was given an understandably cold shoulder. Rather than repeat the unpleasantness, Bailey took to renting them a chaste pair of rooms at the Strand Palace Hotel. Finally, it happened: on a hillside near her home, they made love for the first time.

With their passion consummated, they had to confront Bailey’s marriage and the hostility of Shrimpton’s parents who, astounded that their daughter – still not 19 – was carrying on with a married man, threw her out of the house and shunned her for some time; she and her father didn’t speak for a year. By the summer of ‘61, Bailey and Shrimpton were living in a flat in Primrose Hill with a dog and Bailey’s birds (he would remain an amateur ornithologist his whole life), in a rough, bohemian setting that was at stark odds with their increasingly glamorous lifestyle and public profile.

In the next year, Bailey would become a source of excitable scandal in London: ‘David Bailey/Makes love daily’ went the salacious refrain. And he would become the poster boy for the rise of what one writer would call the ‘photogenes’, the wild young men, primarily, associated with the world of fashion magazines, models, and piles of money. ‘I think the photographer is one of the first completely modern people,’ Bailey was famously quoted as saying. ‘He makes a fortune, he’s always surrounded by beautiful girls, he travels a lot and he’s always living off his nerves in a big-time world.’

Much was made of how cocky East End types like Bailey had broken so completely into what had been a rarefied line of work, and, later on, Bailey acknowledged how timing and history had abetted his rise: ‘Until the ‘60s, the class structure here was almost like the caste system in India. If things had gone on as they were, I would have ended up an untouchable. But that all broke down.’

He didn’t, of course, break it down alone. His key collaborator, who kicked at the status quo with real relish and wicked wit, was Terence Donovan, fellow Cockney crasher of the gilded gates of fashion photography. Big, stout, booming, soft-hearted Donovan was even more of a character than Bailey, a serious practitioner of the martial arts, a man so adverse to cutting a fashionable image that he bought dozens of identical outfits so that he’d never have to think about dressing. He was, too, a prodigious font of comic verbal fancies – rather than admitting to wasting his money on ‘wine, women and song’, he claimed he’d blown a fortune on ‘rum, bum and gramophone’. Donovan was more restless than the other photographers. He was the first to publish a book (women throooo the eyes of smudger TD – the title was his, as was the free association text inside), and he owned a number of businesses completely unrelated to his nominal work: a hardware store in the King’s Road, a building contractors, a chain of dress shops, a restaurant. Eventually, he tried to segue out of still photography altogether, shooting commercials for the majority of his commissions.

But fashion photography, of all fey pursuits, was what he became famous for, and he was soon shooting for Vogue and Queen right alongside Bailey and Brian Duffy. They were always thought of in a group, cowing editors and clients with Cockney sass. ‘Duffy laid it out,’ said Dick Fontaine. ‘They got access to the fashion business by producing this kind of hysteria among the upper-class women who controlled the fashion magazines. They would go in there and be totally East End, acting out in fashion offices. Lady this and that was being beset by these East End boys who were being facetious and not respectful.’ Once they had their feet in the door, the three stereotypically dashed from one exciting assignment to another, partied in chic restaurants and clubs, and ran with beautiful women (Donovan left his first wife for, among others, model Celia Hammond, a classmate of Jean Shrimpton’s at Lucie Clayton’s).

Like Donovan, Bailey kicked against being cast as a fashionista. He did a lot of documentary work, some of it quite fine, like his ‘62 studies of the East End, which had an otherworldly quality reminiscent of Eugene Atget’s work nearly a century earlier. But it was for ‘shifting frocks’, as he derisively referred to the art of fashion photography, that he was famous. And rightly: his April ‘62 Vogue feature – ‘Young Idea Goes West’ – in which Shrimpton was shot on the streets of New York in documentary style, was a landmark that looked breathtaking decades later. There Shrimpton stood – fully clothed, yet somehow naked and fragile, aloof and reserved, a talismanic teddy bear in hand – in Harlem and Chinatown and Greenwich Village, with men ogling her or just as often walking by without a glance. Some of the scenes were dynamically filled with detail, others so spare as to seem posed: brilliant, organic, breakthrough stuff.

New York had been an education for both photographer and model. The British Vogue office had been somewhat nauseated by the prospect of unleashing their bright new Cockney on outsiders. ‘To give you an idea of what it was like then,’ Bailey remembered, ‘Ailsa Garland, the editor of Vogue, phoned me before we left and said, “Don’t wear your leather jacket at the St Regis. Remember you represent British Vogue!"' But Bailey dressed as he pleased: the Vogue chauffeur sent to take him to the airport was horrified to find him waiting in a sweater and jeans. In New York, Miki Denhof, the editor of Glamour, which gave Bailey his first stateside work, remembered her shock on first seeing him: ‘Nobody came to the office in jeans.’ But Diana Vreeland, who’d only recently taken over at American Vogue, knew the real thing the moment she saw it, interrupting the subordinate who was introducing Bailey and Shrimpton with ‘Stop! They are adorable! The English have arrived!’

The majority of American editors weren’t, however, any more prepared to give free rein in their pages to Bailey and his hand-held, freewheeling imagination and imagery than their English counterparts had been. ‘You’re all over the map,’ he was told. In Women’s Wear Daily, the great Richard Avedon dismissed Bailey as ‘a Penn without ink’. And Bailey was even more disappointed at the treatment afforded Shrimpton: ‘It was very square, very “professional”. And what they did to Jean was amazing: they tried to turn her into a kind of doll – stiff hair, too much make-up, over-production. By the time they were finished, it wasn’t really Jean anymore. And it had nothing to do with what we were doing in London at the time, which was much more natural.’

So they became a revolution of two. For the next couple of years – be it in London, New York, Paris or the countryside – Bailey and Shrimpton worked almost exclusively together and, until the rise of the Beatles, were the most glittering jewels in the diadem of the New Aristocracy, the set of young pretties and go-getters whose rise and adventures filled the newspapers and the dreams of young strivers in the East End, South London and the hinterlands.

Bailey, blessed by the money, access and haughty remove his status afforded him, nonetheless harboured a resentful attitude towards the glittery cage in which he believed success had trapped him, and he became frankly bristly when asked about the clichéd image of his life: ‘The whole thing about the East End fashion photographer is that it is perfect for cheap journalism. They always have me talking like a cockney but I don’t think I speak particularly cockney. And in fact I’ve never been out with girls who wear white boots. And I’ve never called a woman a bird.’

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.