Полная версия

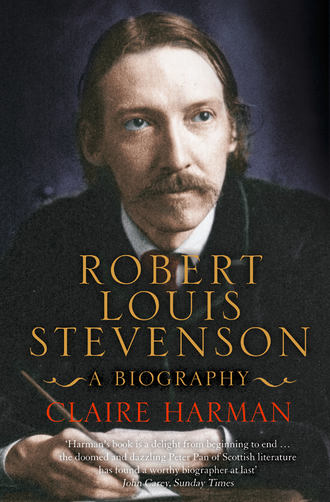

Robert Louis Stevenson: A Biography

The ‘bustling citizen’ most offended by Louis’s eccentricities of behaviour and dress was, of course, his father. Thomas Stevenson was always begging his son to go to the tailor, but when Louis finally succumbed and had a garment made, he chose a dandyish black velvet smoking jacket. He wore this constantly, so it soon lost whatever smartness it had: it was totemic, marking perfectly his difference from the waistcoated and tailed bourgeois of Edinburgh. It declared that although young Stevenson was sometimes confusable with a privileged brat from the New Town, his real milieu was the Left Bank, his true home among artists, connoisseurs, flâneurs.* And in the sanded back-kitchen of the Green Elephant, the Gay Japanee or the Twinkling Eye, ‘Velvet Coat’ became his nickname; the boy of genius, perhaps even the poète maudit.

For a person brought up in such fear for his soul, Stevenson displayed a remarkable fund of basic common sense about sex. Despite their piety, neither of his parents was a prude, and his father’s generous opinions about fallen women predisposed the son to think well of this class of female. Stevenson lost his virginity to one of them while still in his teens, and probably had relations with many more, as this fragment from his 1880 autobiographical notes makes clear:

And now, since I am upon this chapter, I must tell the story of Mary H –. She was a robust, great-haunched, blue-eyed young woman, of admirable temper and, if you will let me say so of a prostitute, extraordinary modesty. Every now and again she would go to work; once, I remember, for some months in a factory down Leith Walk, from which I often met her returning; but when she was not upon the streets, she did not choose to be recognised. She was perfectly self-respecting. I had certainly small fatuity at the period; for it never occurred to me that she thought of me except in the way of business, though I now remember her attempts to waken my jealousy which, being very simple, I took at the time for gospel. Years and years after all this was over and gone, when I was walking sick and sorry and alone, I met Mary somewhat carefully dressed; and we recognised each other with a joy that was, I daresay, a surprise to both. I spent three or four hours with her in a public-house parlour; she was going to emigrate in a few days to America; we had much to talk about; and she cried bitterly, and so did I. We found in that interview that we had been dear friends without knowing it; I can still hear her recalling the past in her sober, Scotch voice, and I can still feel her good honest loving hand as we said goodbye.46

His respectful, even loving, manner must have endeared him to the tarts of the Old Town and encouraged him to develop what was already strong – a romantic sensuousness. He was clearly rather sentimental about women, although he had no neuroses about his dealings with them. But bringing his sexual experience to bear in his writing was another matter altogether.

Prostitutes weren’t the only kind of women that Stevenson associated with; he had plenty of pretty and spirited girl-cousins (there is more than a touch of gallantry in his letters to his cousin Henrietta Traquair), and liked to practise his charm on friends’ sisters. A ‘lady with whom my heart was [ … ] somewhat engaged’ dominated his thoughts in the winter of 1870,47 and if his poems of the time reflect actual experiences, she may have been the girl with whom he played footsie at church (‘You looked so tempting in the pew’48), or the one with whom he skated on Duddingston Loch:

You leaned to me, I leaned to you, Our course was smooth as flight –

We steered – a heel-touch to the left,A heel-touch to the right.

We swung our way through flying men,Your hand lay fast in mine,

We saw the shifting crowd dispart,The level ice-reach shine.

I swear by yon swan-travelled lake,By yon calm hill above,

I swear had we been drowned that dayWe had been drowned in love. 49

Stevenson later admitted to having considered marrying one of the Mackenzie girls (who were neighbours of his engineering professor, Fleeming Jenkin), or Eve, the sister of his friend Walter Simpson, among whose possessions was a lock of the author’s hair. But on the whole he was little attracted to ladylike girls, for reasons suggested by this passage in his 1882 essay, ‘Talk and Talkers’:

The drawing-room is, indeed, an artificial place; it is so by our choice and for our sins. The subjection of women; the ideal imposed upon them from the cradle, and worn, like a hair-shirt, with so much constancy; their motherly, superior tenderness to man’s vanity and self-importance; their managing arts – the arts of a civilised slave among good-natured barbarians – are all painful ingredients and all help to falsify relations.50

In the wake of his later fame, many colourful stories of ran-stam laddishness grew up around Stevenson, mostly revealing an undercurrent of regret that he failed to marry a Scotswoman and died childless.* In 1925, Sidney Colvin was disgusted at the claim in a book (called, baldly, Robert Louis Stevenson, My Father) that Louis had an illegitimate son by the daughter of the blacksmith at Swanston. But while doubting there was any truth in the Swanston claim, even Colvin had to admit ‘we all knew [ … ] that Louis as a youngster was a loose fish in regard to women’.51

Loose fish is better than cold fish (the accusation often aimed at Colvin himself), and however uninhibited Louis was about sex, he retained high notions about chivalry and ‘what is honorable in sentiment, what is essential in gratitude, or what is tolerable by other men’52 in regard to women. This did not include political rights, however. When there were student disturbances in Edinburgh late in 1870 over the admission of women to medical classes, Stevenson wrote to his cousin Maud that he had little sympathy with the ‘studentesses’ who had been hissed at and jostled: ‘Miss Jex-Blake [the lead campaigner] is playing for the esteem of posterity. Soit. I give her posterity; but I won’t marry either her or her fellows. Let posterity marry them, if posterity likes – I won’t.’53 He was to revise his views about New Women somewhat in the coming years.

Stevenson was often subject to fits of morbid melancholy during these years, and wrote to Bob of aimless days looking for distractions, trying to buy hashish, thinking about getting drunk, or hanging round Greyfriars churchyard for hours at a time ‘in the depths of wretchedness’,54 reading Baudelaire, who, he told Bob, ‘would have corrupted St Paul’. The exquisitely self-tormenting notion struck him that he might have already used himself up, that his imagination was, in the potent word of the time, ‘spent’. Alone in an inn at Dunoon in the spring of 1870, he wrote a notebook entry which explicitly links this idea of ‘over-worked imagination’ with the addictive effects of drug-taking:

He who indulges habitually in the intoxicating pleasures of imagination, for the very reason that he reaps a greater pleasure than others, must resign himself to a keener pain, a more intolerable and utter prostration. It is quite possible, and even comparatively easy, so to enfold oneself in pleasant fancies, that the realities of life may seem but as the white snow-shower in the street that only gives a relish to the swept hearth and lively fire within. By such means I have forgotten hunger, I have sometimes eased pain, and I have invariably changed into the most pleasant hours of the day those very vacant and idle seasons which would otherwise have hung most heavily upon my hand. But all this is attained by the undue prominence of purely imaginative joys, and consequently the weakening and almost the destruction of reality. This is buying at too great a price. There are seasons when the imagination becomes somehow tranced and surfeited, as it is with me this morning; and then upon what can one fall back? The very faculty that we have fostered and trusted has failed us in the hour of trial; and we have so blunted and enfeebled our appetite for the others that they are subjectively dead to us. [ … ] Do not suppose I am exaggerating when I talk about all pleasures seeming stale. To me, at least, the edge of almost everything is put on by imagination; and even nature, in these days when the fancy is drugged and useless, wants half the charm it has in better moments. [ … ] I am vacant, unprofitable: a leaf on a river with no volition and no aim: a mental drunkard the morning after an intellectual debauch. Yes, I have a more subtle opium in my own mind than any apothecary’s drug; but it has a sting of its own, and leaves one as flat and helpless as the other.55

Stale, flat, unprofitable: these seem familiar words from a young man intrigued by his own existential dilemmas, and there is more than a touch of speech-making about them, from the expository first sentence to the anticipation of a listener’s responses – ‘Do not suppose I am exaggerating when I talk …’, ‘Yes, I have a more subtle opium …’ For a diary entry it is wonderfully oratorical. Perhaps Stevenson was right to fear losing touch with his imaginative powers, but not through lack of ideas so much as from a surfeit of style.

Stevenson later served up accounts of his youth (in his autobiographical essays) in a manner so inherently witty and objectified that the real pain of it is diluted, but there is a passage in his ‘Chapter on Dreams’ which is revealing about how divided a life he was living at this time. The dream examples in the essay are written in the third person (with the revelation at the end that all the examples are in fact from the writer’s own experience), but the trick seems, if anything, to make the piece more confessional. While ‘the dreamer’ was a student, Stevenson explains, he began to dream in sequence, ‘and thus to live a double life – one of the day, one of the night – one that he had every reason to believe was the true one, another that he had no means of proving to be false’:

[ … ] In his dream-life, he passed a long day in the surgical theatre, his heart in his mouth, his teeth on edge, seeing monstrous malformations and the abhorred dexterity of surgeons. In a heavy, rainy, foggy evening he came forth into the South Bridge, turned up the High Street, and entered the door of a tall land, at the top of which he supposed himself to lodge. All night long, in his wet clothes, he climbed the stairs, stair after stair in endless series, and at every second flight a flaring lamp with a reflector. All night long, he brushed by single persons passing downward – beggarly women of the street, great, weary, muddy labourers, poor scarecrows of men, pale parodies of women – but all drowsy and weary like himself, and all single, and all brushing against him as they passed. In the end, out of a northern window, he would see day beginning to whiten over the Firth, give up the ascent, turn to descend, and in a breath be back again upon the streets, in his wet clothes, in the wet, haggard dawn, trudging to another day of monstrosities and operations.56

Two things are immediately striking about this vivid account: one, that it anticipates so much of Stevenson’s most famous story, The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde – from the medical context, with its ‘monstrous malformations’ to the dismal cityscapes and degrading double-life; the other is the reappearance on every second flight of that endless upward staircase of a flaring ‘lamp with a reflector’, presumably stamped with the maker’s mark, ‘Stevenson and Sons’.

Stevenson implies that these nightmares ‘came true’ in as much as they hung so heavily on him during the day that he never seemed able to recover before it was time to resubmit to them. The account ends bathetically with the information that everything cleared up once he consulted ‘a certain doctor’ and was given ‘a simple draught’ (shades of Jekyll again), but what hangs in the reader’s mind, like the nightmare itself, is what Stevenson admits just before this, that the experience left ‘a great black blot upon his memory’ and eventually made him begin to doubt his own sanity.

In June 1869, Thomas Stevenson took his son with him on the annual tour of inspection aboard the lighthouse steamer Pharos, calling at Orkney, Lewis and Skye. There was plenty to fascinate Louis, but of a romantic, not a technical, nature. At Lerwick he heard all about tobacco and brandy smuggling, and at Fair Isle saw the inlet in which the flagship of the Armada had been wrecked: ‘strange to think of the great old ship, with its gilded castle of a stern, its scroll-work and emblazoning and with a Duke of Spain on board, beating her brains out on the iron bound coast’.57 Not much survives apart from lists of his projected writings from this date, but they show another novel, sketches, stories and rough plans for at least eleven plays (listed in the notebook he took to P.G. Tait’s natural philosophy lectures, the only course he attended with any regularity). But the impression that his engineering experiences (or rather, the long observation of the sea and the Scottish coast they afforded) made on him fuelled his lifetime’s writing. It lies behind many of the autobiographical essays (‘The Coast of Fife’, ‘Rosa Quo Locorum’, ‘Memoirs of an Islet’, ‘On the Enjoyment of Unpleasant Places’, ‘The Education of an Engineer’), short stories such as ‘The Merry Men’, ‘Thrawn Janet’, ‘The Pavilion on the Links’, and the novels Treasure Island, Kidnapped and The Master of Ballantrae.

By the summer of 1870, when Louis was sent on his third consecutive engineering placement, he had begun to enjoy the trips much more. For one thing, there was plenty of sea travel, which he loved, and public steamers allowed him to charm and flirt with new acquaintances in a holiday manner. On the way to the tiny islet of Earraid, which the firm was using as a base for the construction of Dhu Heartach lighthouse, he met the Cumbrian artist Sam Bough, a lawyer from Sheffield, and a pretty and spirited baronet’s daughter called Amy Sinclair: ‘My social successes of the last few days [ … ] are enough to turn anyone’s head,’ he wrote home to his mother.58 The party stopped at Skye and boarded the Clansman returning from Lewis, where their high spirits and monopolisation of the captain’s table were observed by a shy young tourist called Edmund Gosse, son of the naturalist P.H. Gosse, whose struggles to square fundamentalist religious views with the emerging ‘new science’ mirrored very closely those of Thomas Stevenson. Years afterwards, Gosse recorded his initial impressions of the young man who ‘for some mysterious reason’ arrested his attention: ‘tall, preternaturally lean, with longish hair, and as restless and questing as a spaniel’.59 Gosse watched the youth on deck as the sun set, ‘the advance with hand on hip, the sidewise bending of the head to listen’. When the boat stopped unexpectedly a little while later, Gosse saw that they had come up an inlet and that there were lanterns glinting on the shore:

As I leaned over the bulwarks, Stevenson was at my side, and he explained to me that we had come up this loch to take away to Glasgow a large party of emigrants driven from their homes in the interests of a deer-forest. As he spoke, a black mass became visible entering the vessel. Then, as we slipped off shore, the fact of their hopeless exile came home to these poor fugitives, and suddenly, through the absolute silence, there rose from them a wild keening and wailing, reverberated by the cliffs of the loch, and at that strange place and hour infinitely poignant. When I came on deck next morning, my unnamed friend was gone. He had put off with the engineers to visit some remote lighthouse of the Hebrides.60

What they were witnessing in the half-darkness was a latter-day form of Highland ‘clearance’, strongly similar to the notorious forced evictions of the eighteenth century. Stevenson does not mention Gosse at all or this incident in his letters home (which were too taken up with Miss Amy Sinclair), but it must surely be the inspiration for the scene in Chapter 16 of Kidnapped – written sixteen years later – when David Balfour sees an emigrant ship setting off from Loch Aline:

the exiles leaned over the bulwarks, weeping and reaching out their hands to my fellow-passengers, among whom they counted some near friends. [ … ] the chief singer in our boat struck into a melancholy air, which was presently taken up both by the emigrants and their friends upon the beach, so that it sounded on all sides like a lament for the dying. I saw the tears run down the cheeks of the men and women in the boat, even as they bent at the oars.61

Earraid itself, where Stevenson was headed on the Clansman, figured prominently in Kidnapped as the isle of Aros, on which David Balfour believes himself to be stranded. It was his first view of Earraid, isolated and empty except for one cotter’s hut, that Stevenson reproduced in the novel; when the firm was there in 1870, the islet had been transformed into a bustling work-station, with sheds, a pier, a railway, a quarry, bothies for the workmen, an iron hut for the chief engineer and a platform on which parts of the lighthouse were preconstructed. The reef where the lighthouse was to be built, fifteen miles away, was watched through a spyglass, and when the water was low, the engineers would put out for it in a convoy of tenders and stone-lighters. The scene on Dhu Heartach was another one of industrial despoliation: ‘the tall iron barrack on its spider legs, and the truncated tower, and the cranes waving their arms, and the smoke of the engine-fire rising in the mid-sea’.62

Stevenson’s letters home to his parents from Earraid were typically charming, affectionate and frank. He sought to be a good son, and bore his parents’ feelings in mind to an extraordinary degree, perhaps too much for his own good. He did not share all their values by any means, found many of their strictures infuriating or risible, deceived them to the usual degree in such cases, yet felt what amounts to a profound sympathy for their predicament qua parents and never ceased to respect and love them. ‘It is the particular cross of parents that when the child grows up and becomes himself instead of that pale ideal they had preconceived, they must accuse their own harshness or indulgence for this natural result,’ he wrote in an uncollected essay.63 ‘They have all been like the duck and hatched swan’s eggs, or the other way about; yet they tell themselves with miserable penitence that the blame lies with them; and had they sat more closely, the swan would have been a duck, and home-keeping, in spite of all.’64 Thus he continued – for the time being – to be a staunch religionist (writing to the approved Church of Scotland paper on subjects such as foreign missions), a good Tory (he was treasurer of the University Conservative Club in 1870) and a passable student of engineering. But it couldn’t last long, and didn’t.

The winter of 1870–71 saw Stevenson’s first real opportunity to associate with other would-be writers, and the effect was galvanising. Three law students in the Speculative Society, James Walter Ferrier, Robert Glasgow Brown and George Omond, approached Stevenson to join them in editing a new periodical, the Edinburgh University Magazine. They had already found a publisher (the local booksellers), and were going to share the expenses and the profits. Of course, the likelihood of there being profits was nil and the magazine only ran for four issues, but in those four Stevenson published six articles and edited one whole number on his own. Being recognised as a fellow writer was ‘the most unspeakable advance’, he said later: ‘it was my first draught of consideration; it reconciled me to myself and to my fellow-men’.65

Ferrier, the golden youth of this group, was to become one of Stevenson’s best friends. Witty, wealthy and devastatingly handsome, he seemed destined for great things and was the first of these ambitious young writers to publish a book, a novel called Mottiscliffe: An Autumn Story. Robert Glasgow Brown also had early literary success, founding a weekly magazine called London in 1877, to which Stevenson and most of their group contributed. Louis’s best friend, however, was a young lawyer whom he had known socially through attending the same Edinburgh church, St Stephen’s. Charles Baxter was two years older than Louis and had graduated from the university in 1871, entering his father’s chambers as an apprentice. Temperamentally the two young men had much in common: Baxter was idle, sentimental, and ready for any sort of practical joking. He was the ideal drinking companion and had a droll turn of phrase that was a perfect foil for Louis’s high spirits and semi-hysterical flights of fancy. An anecdote that Baxter told of his first visit to Swanston makes it easy to see what Louis valued in this amiable youth:

That night, late, in his bedroom, after reading to me (I think) ‘The Devil on Crammond Sands’, he flung himself back on his bed in a kind of agony exclaiming, ‘Good God, will anyone ever publish me!’ To soothe him, I (quite insincerely) assured him that of course someone would, for I had seen worse stuff in print myself.66

Baxter was put up for the Spec by Stevenson and became Secretary (he was always good with procedure, as befitted his profession). But their happiest times were spent on the streets of Edinburgh, engaged in jokes against fogeys such as the ill-tempered wine merchant Brash, whom Stevenson made the hero of a set of ribald verses, or talking to each other in ludicrously broad Scots, in the character of two old Edinburgh lawyers, Johnson and Thomson. Spontaneous jokes were their speciality, like the time they followed six men carrying a wrapped sheet of glass down George Street, as if they were chief mourners, hats off and heads bowed. As Louis wrote in one of his ‘Brasheana’ poems, ‘Let us be fools, my friend, let us be drunken,/Let us be angry and extremely silly.’67

In the spring of 1871 Louis was called on to give a paper to the Royal Scottish Society of Arts, and made a fair effort at pleasing both the examining committee and his father. One of the examiners was his professor of engineering, Fleeming” Jenkin, whose early dealings with the student had not been promising. Stevenson had applied to him for one of the necessary certificates of attendance at the end of the first year, only to be told that as far as the professor was aware, his attendance had been nil. ‘It is quite useless for you to come to me, Mr Stevenson,’ Jenkin had said. ‘There may be doubtful cases; there is no doubt about yours. You have simply not attended my class.’68 The frankness of this impressed the truant, and Jenkin turned out to be one of the few older men towards whom Louis showed admiration and respect.

‘On a New Form of Intermittent Light’ is very short for a paper – ten pages of large writing, the last sentences of which have been written in a different ink and possibly a different hand: ‘It must however, be noted, that none of these last methods are applicable to cases where more than one radiant is employed: for these cases either my grandfather’s or Mr Wilson’s contrivance must be resorted to’69 – an anxious note, which suggests Thomas Stevenson looking over his boy’s first contribution to science. The substance of Louis’s proposal is that a revolving hemispherical mirror could be used in conjunction with a fixed mirror to make lighthouse lights flash. The ‘revolving’ part of this idea was ingenious, though from his very rudimentary diagrams it is clear that the student had given little thought to the technical and logistical difficulties. Nevertheless, Jenkin and his colleagues judged the paper ‘specially noteworthy’ and later in the year awarded this latest scion of the Stevenson family a silver medal for his trouble.*

Thomas Stevenson was, presumably, not so impressed by his son’s performance, for it was only about ten days later that he chose an evening walk as the occasion to grill Louis on his intentions. The conversation was painful and upsetting for both, for the youth, ‘tightly cross-questioned’,71 confessed that he cared for nothing but literature. Thomas had at last to swallow the fact that the experiment had gone on long enough, and had been a failure. Louis had spent four years studying at the university, three summers on the works, he had worked in a carpenter’s shop, a foundry and a timberyard, and still couldn’t tell one kind of wood from another or make the most basic calculations. They were flogging a dead horse.