Полная версия

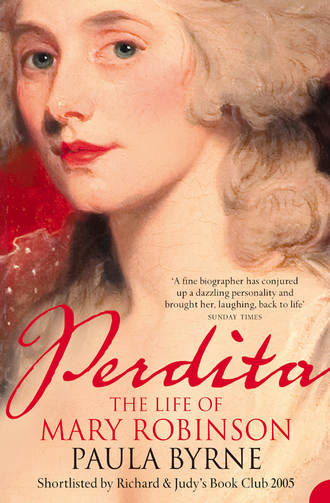

Perdita: The Life of Mary Robinson

Perdita

THE LIFE OF MARY ROBINSON

PAULA BYRNE

DEDICATION

In memory of my grandmother,another Mary Robinson

EPIGRAPH

I was delighted at the Play last Night, and was extremely moved by two scenes in it, especially as I was particularly interested in the appearance of the most beautiful Woman, that ever I beheld, who acted with such delicacy that she drew tears from my eyes.

(George, Prince of Wales)

There is not a woman in England so much talked of and so little known as Mrs Robinson.

(Morning Herald, 23 April 1784)

I was well acquainted with the late ingenious Mary Robinson, once the beautiful Perdita … the most interesting woman of her age.

(Sir Richard Phillips, publisher)

She is a woman of undoubted Genius … I never knew a human Being with so full a mind – bad, good, and indifferent, I grant you, but full, and overflowing.

(Samuel Taylor Coleridge)

I am allowed the power of changing my form, as suits the observation of the moment.

(Mary Robinson, writing as ‘The Sylphid’)

CONTENTS

COVER

TITLE PAGE

DEDICATION

EPIGRAPH

PROLOGUE

PART ONE: ACTRESS

1. ‘During a Tempestuous Night’

2. A Young Lady’s Entrance into the World

3. Wales

4. Infidelity

5. Debtors’ Prison

6. Drury Lane

7. A Woman in Demand

PART TWO: CELEBRITY

8. Florizel and Perdita

9. A Very Public Affair

10. The Rivals

11. Blackmail

12. Perdita and Marie Antoinette

13. A Meeting in the Studio

14. The Priestess of Taste

15. The Ride to Dover

16. Politics

PART THREE: WOMAN OF LETTERS

17. Exile

18. Laura Maria

19. Opium

20. Author

21. Nobody

22. Radical

23. Feminist

24. Lyrical Tales

25. ‘A Small but Brilliant Circle’

P.S. IDEAS, INTERVIEWS & FEATURES …

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Q AND A WITH PAULA BYRNE

LIFE AT A GLANCE

TOP TEN BOOKS

ABOUT THE BOOK

CELEBRITY

READ ON

HAVE YOU READ?

IF YOU LOVED THIS, YOU MIGHT LIKE …

FIND OUT MORE

EPILOGUE

APPENDIX: THE MYSTERY OF MRS ROBINSON’S AGE

BIBLIOGRAPHY

INDEX

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

NOTES

PRAISE

OTHER WORKS

COPYRIGHT

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

PROLOGUE

In the middle of a summer night in 1783 a young woman set off from London along the Dover road in pursuit of her lover. She had waited for him all evening in her private box at the Opera House. When he failed to appear, she sent her footman to his favourite haunts: the notorious gaming clubs Brooks’s and Weltje’s; the homes of his friends, the Prince of Wales, Charles James Fox, and Lord Malden. At 2 a.m. she heard the news that he had left for the Continent to escape his debtors. In a moment of panic and desperation, she hired a post chaise and ordered it to be driven to Dover. This decision was to have the most profound consequences for the woman famous and infamous in London society as ‘Perdita’.

In the course of the carriage ride she suffered a medical misadventure.* And she did not meet her lover at Dover: he had sailed from Southampton. Her life would never be the same again.

Born Mary Darby, she had been a teenage bride. As a young mother she was forced to live in debtors’ prison. But then, under her married name of Mary Robinson, she had been taken up by David Garrick, the greatest actor of the age, and had herself become a celebrated actress at Drury Lane. Many regarded her as the most beautiful woman in England. The young Prince of Wales – who would later become Prince Regent and then King George IV – had seen her in the part of Perdita and started sending her love letters signed ‘Florizel’. She held the dubious honour of being the first of his many mistresses.

In an age when most women were confined to the domestic sphere, Mary was a public face. She was gazed at on the stage and she gazed back from the walls of the Royal Academy and the studios of the men who painted her, including Sir Joshua Reynolds, who was to painting what Garrick was to theatre. The royal love affair also brought her image to the eighteenth-century equivalent of the television screen: the caricatures displayed in print-shop windows. Her notoriety increased when she became a prominent political campaigner. In quick succession, she was the mistress of Charles James Fox, the most charismatic politician of the age, and Colonel Banastre Tarleton, known as ‘Butcher’ Tarleton because of his exploits in the American War of Independence. The prince, the politician, the action hero: it is no wonder that she was the embodiment of – the word was much used at the time, not least by Mary herself – ‘celebrity’.

Her body was her greatest asset. When she came back from Paris with a new style of dress, everyone in the fashionable world wanted one like it. When she went shopping, she caused a traffic jam. What was she to do when that body was no longer admired and desired?

Fortunately, she had another asset: her voice. Whilst still a teenager, she had become a published poet. Because of her stage career, she had an intimate knowledge of Shakespeare’s language – and the ability to speak it. So, as her health gradually improved, she remade herself as a professional author. Having transformed herself from actress to author, she went on to experiment with a huge range of written voices, as is apparent from the variety of pseudonyms under which she wrote: Horace Juvenal, Tabitha Bramble, Laura Maria, Sappho, Anne Frances Randall. She completed seven novels (the first of them a runaway bestseller), two political tracts, several essays, two plays and literally hundreds of poems.1

Actress, entertainer, author, provoker of scandal, fashion icon, sex object, darling of the gossip columns, self-promoter: one can see why she has been described as the Madonna of the eighteenth century.2 But celebrity has its flipside: oblivion. Mary Robinson had the unique distinction of being painted in a single season by the four great society artists of the age – Sir Joshua Reynolds, Thomas Gainsborough, John Hoppner, and George Romney – and yet within a few years of her death the Gainsborough portrait was being catalogued under the anonymous title Portrait of a Lady with a Dog. In the twentieth century, despite the resurgence of the art of life-writing and the enormous interest in female authors, there was not a single biography of Robinson. Before the Second World War, she was considered suitable only for fictionalized treatments, historical romances and bodice-rippers with titles such as The Exquisite Perdita and The Lost One. In the 1950s her life was subordinated to that of the lover she thought she was pursuing to France.* A book on George IV and the women in his life did not even mention Mary’s name, despite the fact that she was his first love and he remained in touch with her for the rest of her life.3 Finally in the 1990s, feminist scholars began a serious reassessment of Robinson’s literary career. However, their work was aimed at a specialized audience of scholars and students of the Romantic period in literature.4

When Mary Robinson began writing her autobiography, near the end of her life, there were two conflicting impulses at work. On the one hand, she needed to revisit her own youthful notoriety. She had been the most wronged woman in England and she wanted to put on record her side of the story of her relationship with the Prince of Wales. But at the same time, she wanted to be remembered as a completely different character: the woman of letters. As she wrote, she had in her possession letters from some of the finest minds of her generation – Samuel Taylor Coleridge, William Godwin, Mary Wollstonecraft – assuring her that she was, in Coleridge’s words, ‘a woman of genius’. Royal sex scandal and the literary life do not usually cohabit between the same printed sheets, but in a biography of the woman who went from ‘Mrs Robinson of Drury Lane’ to ‘the famous Perdita’ to ‘Mary Robinson, author’, they must.

The research for this book took me from the minuscule type of the gossip columns of the Morning Herald in the newspaper division of the British Library at Colindale in north London to the Gothic cloister of Bristol Minster, where Mary Robinson was born. I stood below the incomparable portraits of her in the Wallace Collection tucked away off busy Oxford Street and in stately homes both vast (Waddesdon Manor) and intimate (Chawton House). In the Print Room of the British Museum I pored over graphic and sometimes obscene caricatures of her; via the worldwide web I downloaded long-forgotten political pamphlets in which she figured prominently; in the New York Public Library, within earshot of the traffic on Fifth Avenue, I pieced together the letters in which Mary revealed her state of mind in the final months of her life, as she continued to write prolifically even as she struggled against illness and disability.

I found hitherto neglected letters and manuscripts scattered in the most unlikely places: in a private home in Surrey, I opened a cardboard folder and found the Prince of Wales’s account of the night he saw ‘Perdita’ at Drury Lane, written the very next day, in the first flush of his infatuation with her; in the Garrick Club, among the portraits of the great men of the theatre who launched Mary’s career, I discovered a letter in which she laid out her plan to rival the Lyrical Ballads of Wordsworth and Coleridge; and in one of the most securely guarded private houses in England – which I am prohibited from naming – I found the original manuscript of her Memoirs, which is subtly different from the published text. I became intimate with the perfectly proportioned face and the lively written voice of this remarkable woman. Yet as I was researching the book, people from many walks of life asked me who I was writing about: hardly any of them had heard of the eighteenth-century Mary Robinson. So I have sought to recreate her life, her world and her work, and to explain how it was that one of her contemporaries called her ‘the most interesting woman of her age’.5

*As with many incidents in her life, the circumstances are not absolutely clear, as will be seen in chapter 15.

*Robert Bass, The Green Dragoon: The Lives of Banastre Tarleton and Mary Robinson (New York, 1957) – as the title reveals, the main emphasis is on Tarleton’s military career. Though Bass undertook valuable archival research, his transcriptions were riddled with errors, he misdated key incidents, and he failed to notice many fascinating newspaper reports, references in memoirs, and other sources. It is no exaggeration to say that his inaccuracies outnumber his accuracies: if Bass says that an article appeared one November in the Morning Post, one may rest assured that it is to be found in December in the Morning Herald.

CHAPTER 1 ‘During a Tempestuous Night’

The very finest powers of intellect, and the proudest specimens of mental labour, have frequently appeared in the more contracted circles of provincial society. Bristol and Bath have each sent forth their sons and daughters of genius.

Mary Robinson, ‘Present State of the Manners, Society, etc.

etc. of the Metropolis of England’

Horace Walpole described the city of Bristol as ‘the dirtiest great shop I ever saw’. Second only to London in size, it was renowned for the industry and commercial prowess of its people. ‘The Bristolians,’ it was said, ‘seem to live only to get and save money.’1 The streets and marketplaces were alive with crowds, prosperous gentlemen and ladies perambulated under the lime trees on College Green outside the minster, and seagulls circled in the air. A river cut through the centre, carrying the ships that made the city one of the world’s leading centres of trade. Sugar was the chief import, but it was not unusual to find articles in the Bristol Journal announcing the arrival of slave ships en route from Africa to the New World. Sometimes slaves would be kept for domestic service: in the parish register of the church of St Augustine the Less one finds the baptism of a negro named ‘Bristol’. Over the page is another entry: Polly – a variant of Mary – daughter of Nicholas and Hester Darby, baptized 19 July 1758.2

Nicholas Darby was a prominent member of the Society of Merchant Venturers, based at the Merchants’ Hall in King Street, an association of overseas traders that was at the heart of Bristol’s commercial life. The merchant community supported a vibrant culture: a major theatre, concerts, assembly rooms, coffee houses, bookshops, and publishers. Bristol’s most famous literary son was born just five years before Mary. Thomas Chatterton, the ‘marvellous boy’, was the wunderkind of English poetry. His verse became a posthumous sensation in the years following his suicide (or accidental self-poisoning) at the age of 17. For Keats and Shelley, he was a hero; Mary Robinson and Samuel Taylor Coleridge both wrote odes in his memory.

Coleridge himself also developed Bristol connections. His friend and fellow poet Robert Southey, the son of a failed linen merchant, came from the city. The two young poets married the Bristolian Fricker sisters and it was on College Green, a stone’s throw from the house where Mary was born, that they hatched their ‘pantisocratic’ plan to establish a commune on the banks of the Susquehanna River.

Mary described her place of birth at the beginning of her Memoirs. She conjured up a hillside in Bristol, where a monastery belonging to the order of St Augustine had once stood beside the minster:

On this spot was built a private house, partly of simple and partly of modern architecture. The front faced a small garden, the gates of which opened to the Minster-Green (now called the College-Green): the west side was bounded by the Cathedral, and the back was supported by the antient cloisters of St Augustine’s monastery. A spot more calculated to inspire the soul with mournful meditation can scarcely be found amidst the monuments of antiquity.

She was born in a room that had been part of the original monastery. It was immediately over the cloisters, dark and Gothic with ‘casement windows that shed a dim mid-day gloom’. The chamber was reached ‘by a narrow winding staircase, at the foot of which an iron-spiked door led to the long gloomy path of cloistered solitude’. What better origin could there have been for a woman who grew up to write best-selling Gothic novels? If the Memoirs is to be believed, even the weather contributed to the atmosphere of foreboding on the night of her birth. ‘I have often heard my mother say that a more stormy hour she never remembered. The wind whistled round the dark pinnacles of the minster tower, and the rain beat in torrents against the casements of her chamber.’ ‘Through life,’ Mary continued, ‘the tempest has followed my footsteps.’3

The Minster House was destroyed when the nave of Bristol Minster was enlarged in the Victorian era, but it is still possible to stand in the courtyard in front of the Minster School and see the cloister that supported the house in which Mary was born. And next door, in what is now the public library, one can look at an old engraving which reveals that the house was indeed tucked beneath the great Gothic windows and the mighty tower of the cathedral itself.

The family had Irish roots. Mary’s great-grandfather changed his name from MacDermott to Darby in order to inherit an Irish estate. Nicholas Darby was born in America and claimed kinship with Benjamin Franklin.4 As a young man he was engaged in the Newfoundland fishing trade in St John’s. His daughter described him as having a ‘strong mind, high spirit, and great personal intrepidity’, traits that could equally apply to herself.5

Mary was always touchy about issues of rank and gentility. In her Memoirs she took pains to emphasize the respectability of the merchant classes. Her father had some success in cultivating the acquaintance of the aristocracy: in an unpublished handwritten note, Mary remarked with pride that ‘Lord Northington the Chancellor was my Godfather’ and that at her christening ‘the Hon Bertie Henley stood for him as proxy’.6

Mary’s mother, Hester, née Vanacott, made a romantic match with Nicholas Darby when she married him on 4 July 1749 in the small Somerset village of Donyatt. Hester was a descendant of a well-to-do family, the Seys of Boverton Castle in Glamorganshire, and a distant relation (by marriage) of the philosopher John Locke. Vivacious and popular, she had many suitors and her parents would have expected her to marry into a landed family. They did not approve of her union with Darby.

In 1752, three years after their marriage, Nicholas and Hester had a son, whom they named John.7 A daughter called Elizabeth followed in January 1755. She died of smallpox before she was 2 and was buried in October 1756. It was a great comfort to Nicholas and Hester when Mary was born just over a year later, on 27 November 1757.*

In the days before vaccination, smallpox was a lethal threat to children. The disease took not only the infant Elizabeth, but probably also a younger brother, William, when he was 6. Another younger brother for Mary, named George, fared better: he and John both grew up to become ‘respectable’ merchants, trading at Leghorn (Livorno) in Italy.

Hester soon found that she had entered into an unhappy union. Nicholas spent much of his time in Newfoundland on business. By 1758, he was putting down roots there, joining with other merchants in an enterprise to build a new church. He returned to Bristol for the winter months, but he can only have been a shadowy presence in his daughter’s early life.

The Darby boys were extremely handsome, with auburn hair and blue eyes. Mary took after her father; she described her own childhood looks as ‘swarthy’, with enormous eyes set in a small, delicate face. She was a dreamy, melancholy, and pensive child who revelled in the gloominess of her surroundings in the minster. The children’s nursery was so close to the great aisle that the peal of the organ could be heard at morning and evening service. Mary would creep out of her nursery on her own and perch on the winding staircase to listen to the music: ‘I can at this moment recall to memory the sensations I then experienced, the tones that seemed to thrill through my heart, the longing which I felt to unite my feeble voice to the full anthem, and the awful though sublime impression which the church service never failed to make upon my feelings.’ Rather than playing on College Green with her brothers she would creep into the minster to sit beneath the lectern in the form of a great eagle that held up the huge Bible. The only person who could keep her away from her self-imposed exile there was the stern sexton and bell-ringer she named Black John, ‘from the colour of his beard and complexion’.8

As soon as she learnt to read, she recited the epitaphs and inscriptions on the tombstones and monuments. Before she was 7 years old, she had memorized several elegiac poems that were typical of the verse of the eighteenth century. Her taste in music was as mournful as her taste in poetry.

Mary confessed that the events of her life had been ‘more or less marked by the progressive evils of a too acute sensibility’. One thinks here of Jane Austen’s first published novel, Sense and Sensibility, with its satirical portrait of the ultra-sensitive Marianne Dashwood: she bears more than a passing resemblance to the melancholy young Mary Darby, quoting morbid poetry and thoroughly enjoying the misery of playing sombre music and being left in solitary contemplation. As a writer, Mary was always acutely aware of her audience: her image of herself in the Memoirs as a child of sensibility was designed to appeal to the numerous readers of Gothic novels and sentimental fiction. At the same time, her self-image appealed to the romantic myth of the writer as a natural genius who begins as a precociously talented but lonely child escaping into the world of imagination.

Though Mary presented herself as a ‘natural’ genius, she was the beneficiary of improvements in education and the growth of printed literature aimed at a young audience. This was a period when private schools for girls of middling rank sprang up all over England. Bristol was the home of Hannah More, playwright, novelist, Evangelical reformer, and political writer. Though Hannah became famous for rectitude and Mary for scandal, their lives were curiously parallel: born and bred in Bristol, each of them had a theatrical career that began under the patronage of David Garrick and each then turned to the art of the novel. In the 1790s they both became associated with contentious debates about women’s education.

Mary attended a school run by Hannah More and her sisters. An upmarket ladies’ academy, it had opened in 1758 in Trinity Street, behind the minster, just a few hundred yards from Mary’s birthplace. The curriculum concentrated on ‘French, Reading, Writing, Arithmetic, and Needlework’. A recruitment advertisement added that ‘A Dancing Master will properly attend.’9 The school was immensely popular and four years later moved to 43 Park Street, halfway up the hill towards the genteel district of Clifton. When Mary Darby attended, the enrolment had risen to sixty pupils. Each of the More sisters took responsibility for a different ‘department’ of the curriculum, with – in Mary’s words – ‘zeal, good sense and ability’. The earnest and erudite Hannah ‘divided her hours between the arduous task “of teaching the young ideas how to shoot,” and exemplifying by works of taste and fancy the powers of a mind already so cultivated’.10

In the summer of 1764 Bristol was in the grip of theatre mania. The famous London star William Powell played King Lear with a force said to rival that of the great Garrick himself. Within two years Powell was combining management with performance at a new building in the city centre. The first theatre in England to be built with a semicircular auditorium, it had nine dress boxes and eight upper side boxes, all inscribed with the names of renowned dramatists and literary figures.

The highlight of the first season in this new Theatre Royal was another King Lear, with Powell in the lead once again and his wife Elizabeth playing Cordelia. Powell had become very friendly with Hannah More, and she wrote an uplifting prologue for the performance. The whole school turned out for the play. It was the 8-year-old Mary Darby’s first visit to the theatre. She vividly remembered the ‘great actor’ of whom Chatterton said ‘No single part is thine, thou’rt all in all.’11 She was less taken by the performance of his wife who played Cordelia without ‘sufficient éclat to render the profession an object for her future exertions’.12 Among Mary’s school friends were Powell’s two daughters and the future actress Priscilla Hopkins, who would later become the wife of John Kemble and sister-in-law of Sarah Siddons, the most famous actress in Britain. The girls developed a passion for theatre together.