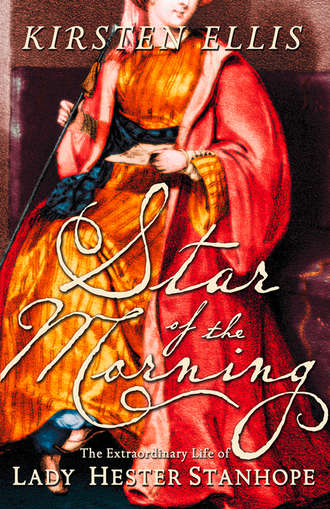

Star of the Morning: The Extraordinary Life of Lady Hester Stanhope

Полная версия

Star of the Morning: The Extraordinary Life of Lady Hester Stanhope

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента

Купить и скачать всю книгу