Полная версия

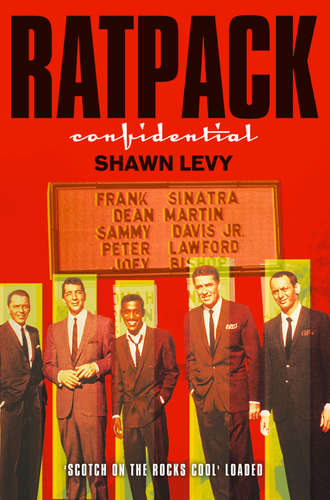

Rat Pack Confidential

It was a sign of his own success. Into his forties, he had come to see himself as a man of station and discernment, a world-beater worthy of helping shape the future. But it was also a kind of inheritance: He had learned about politics by watching his mother work the ward system in Hoboken. Dolly Sinatra had the barest formal education and should’ve been kept from achieving any kind of power as a woman, an immigrant, as a midwife and abortionist. But she had spunk: She married a Sicilian against her Genoese parents’ will; she dressed up like a man to watch her husband box in men-only joints; she exploited her fair features to pass herself off as Irish; she drank; and she talked like a stevedore, cursing vividly even when, in her dotage, attended constantly by a nun.

Such spirit distinguished her from other Italian mothers of her generation, but not so dramatically as did her political activities. In a corrupt little town run by an ironclad political machine, she won over the kingmakers by consistently turning out the vote and becoming the person to whom her neighbors came for jobs, food, and the sort of generic wheel-greasing and ass-saving they associated with Men of Respect. Dolly, of course, could never hold office, but she had the ears of men who could forgive crimes, erase debts, grant sinecures, and make life bearable or hellish as they chose. With her assistance, scores of Hoboken’s Italians made their way toward the better life they’d come to America to enjoy.

Dolly didn’t achieve her station simply by virtue of gumption. She worked hard at her glad-handing and ward-heeling, and she was even willing to broker her only child for political advantage; as his godfather, she chose none of his five uncles or other male relatives but Frank Garrick, an Irish newspaperman whose uncle was a police captain. The choice proved strangely fateful. In a mix-up that marked the child forever, the priest at the baptism named the boy Francis—for Garrick, whom he somehow came to believe was the father—instead of Martin, the name Dolly and Marty had chosen. Dolly, still recuperating from the delivery, wasn’t at the ceremony to protest, while Marty stood there in characteristically mute impotence, saying nothing as his patrimony was diluted.

For all that she fussed over her boy, for all the clothes and spending cash and good words put in with people who could get him jobs and, later, gigs, Dolly nevertheless found it more exigent to leave him to the care of others and pursue her political work. Frank was fobbed off on relatives and neighbors. Politics, in effect, was the sibling from whose charms he could never divert his mother’s eye; naturally, it came to seem to him an extension of family life, a way of linking up with his absent mother and creating a community around himself.

Plus it had perks. Dolly got Marty a well-paying job in the city fire department despite his inability to pass a written test, and she eventually got him promoted to captain—though few of his colleagues reckoned him worthy of the honor. Comfort and largesse flowed from political power, Frank could see, and when he was old enough to court it he did.

Frank’s political instincts weren’t entirely mercenary. He genuinely felt compassion for the underdog and championed civil rights as soon as he had a platform from which to be heard. In 1945, virtually the moment his career as a solo artist granted him a public profile, he spoke out against prejudice at a high school in Gary, Indiana, where black students had recently been admitted to a hostile reception from whites.

He also godfathered a curious little film project, The House I Live In, a ten-minute docudrama in which he preached a lesson in ethnic harmony to a mixed-race gang of street kids. “Look, fellas, religion makes no difference except to a Nazi or somebody as stupid,” he explained. “My dad came from Italy, but I’m an American. Should I hate your father ’cause he came from Ireland or France or Russia? Wouldn’t that make me a first-class fathead?” Then he launched into the title song, a syrupy ode to American equality, and ended by admonishing his audience of converted Schweitzers, “Don’t let ’em make suckers out of you.” (The film won Special Academy Awards for its creators, including Sinatra, director Mervyn LeRoy, and screenwriter Albert Maltz, a future member of the famous Hollywood Ten group of blacklisted authors.)

And Frank practiced what he preached. He was among the earliest and most visible proponents of civil rights in all of show business. He worked and traveled with black musicians, always insisting that they get treatment equal to that afforded him in restaurants and hotels, and he did what he could to give a boost to such acts as the Will Mastin Trio.

Frank’s political liberalism even led him to a deliberate reprise of the accident that gave him his own name. His only son was always known as Frank Jr., but the kid was actually named Franklin Wayne Emmanuel Sinatra in tribute to, among others, his father’s hero Franklin Roosevelt.

And he didn’t merely communicate his convictions in symbols. On the night in 1944 that FDR beat Thomas Dewey, Frank, in New York for a series of concerts at the Waldorf-Astoria, celebrated with a bar crawl in the company of Orson Welles. The two decided to cap their gambols by razzing right-wing columnist Westbrook Pegler, also resident at the hotel. They rowdily pounded the door to Pegler’s suite to no satisfactory response, then returned, discouraged, to their debauch.

Four years later, Frank won $25,000 on a bet that Harry Truman would be reelected. In 1952, Frank campaigned for Adlai Stevenson, and then again in 1956, when he sang the national anthem at the opening session of the Democratic National Convention in Chicago and stuck around to get a close-up look at the action. (He caused some of his own as well. After he sang “The Star-Spangled Banner,” Frank was on his way offstage when he was grabbed by Speaker of the House Sam Rayburn, who asked him if he’d also be performing “The Yellow Rose of Texas.” “Get your hands off the suit, creep,” Sinatra replied.)

It was there that his eye was first caught by Jack Kennedy, then a dazzling, photogenic young senator with a pretty wife and a baby on the way. After Stevenson had secured the presidential nomination, he’d thrown the vice-presidential slot to the convention without naming a candidate of his preference; Kennedy, against his father’s wishes, sought the spot and was locked in battle for it with Tennessee’s Mafia-baiting senator, Estes Kefauver. Frank hung close to the Kennedys as the convention progressed, impressed with the amount of money and degree of organization the family applied to the campaign. When Kefauver won the nomination, the Kennedys were briefly stunned.

Then Frank noticed Bobby, the senator’s younger brother and campaign manager, telling folks around him, “OK, that’s it. Now we go to work for the next one.” The stubborn will in those words was invitingly familiar, an echo of Dolly’s gumption. Frank determined to keep tabs on Jack Kennedy.

He just needed an in.

And what do you know: At a dinner party at Gary and Rocky Cooper’s house in the summer of ’58, there was Peter.

Frank had seen Lawford among his in-laws at the Democratic convention two years earlier; he was working, incongruously, with Bobby, trying to gain support from the Nevada delegation, which was run by Peter’s sometime Desert Inn boss, Wilbur Clark.

At the time, even though they’d been chummy at MGM in the forties, Frank was carrying a grudge against Peter—a misunderstanding about a woman. In late ’53, after she and Frank had split, Ava Gardner had a drink with Peter at an L.A. nightspot. When Louella Parsons reported the little tête-à-tête, Frank went bonkers, calling Peter at two in the morning and shouting at him, “Do you want your legs broken, you fucking asshole? Well, you’re going to get them broken if I ever hear you’re out with Ava again. So help me, I’ll kill you.”

Peter was terrified: “Frank’s a violent guy and he’s good friends with too many guys who’d rather kill you than say hello.” He asked a friend to intervene, and when Frank realized that it really was just an innocent drink, he cooled off. But he didn’t bother with Peter until he’d become a Kennedy, and even then grudgingly. Pat Kennedy, presuming with some reason to install herself as a society queen in Hollywood, had tried for years to have Frank attend some or other event; he had always brusquely refused her.

But as her brother’s star rose, and as Frank’s interest in politics merged subtly with his naked ambition, Peter’s near-trespass didn’t seem so awful. So it came to pass that on that fateful night at the Coopers’, with Peter working late at the studio on his Thin Man TV series, Pat found herself rapt in conversation with Frank, who had gone out of his way to break the ice with her. Dolly Sinatra’s boy, ever aware of who held the power, knew that she could provide quite a high level of access to what was clearly a growing political concern.

When Peter arrived at the party—bandaged after an injury on the set—he was amazed to discover his wife and Frank amiably chatting. He quietly took a seat at the table, not knowing what sort of greeting to expect. Frank looked at him, then looked back at Pat and said, “You know, I don’t speak to your old man.” The two of them laughed, and Peter did, too, a beat later, when he realized he’d been forgiven.

Within a few months, a suddenly intimate relationship formed between Peter and Frank. When Pat had a daughter that November, the child was christened Victoria Francis—the first name in recognition of her Uncle Jack’s reelection to the Senate that day, the second in recognition of Frank.

The following year, vacationing together in Rome, Frank actually apologized to Peter for the way he’d blown up over Ava: “Charlie, I’m sorry. I was dead wrong.” It was the rarest of moments: another smile of fate upon Peter Lawford.

He and Frank became fast pals, frat brothers with nicknames, booze, broads, matching cars. He got work: the Pacific theater war movie Never So Few, his first picture in six years, came his way strictly because Frank insisted on it—and at a price that made MGM choke, also at Frank’s insistence. The two became partners in a Beverly Hills restaurant, Puccini, and served spaghetti and chops to the stars; Frank was so glad to have Peter on board that he put up both halves of the seed money.

And Frank had his avenue to Jack Kennedy. Peter admitted that he and his wife “were very attractive to Frank because of Jack.” Sure enough, once he was connected, Frank leapfrogged over the guy he came to call “the brother-in-Lawford” and ingratiated himself with both Jack and Old Joe.

Indeed, though his cavorting with Jack was famous, Frank may have been closer to the father, the primary source of money and power in the family and the one most familiar with the courtship of disreputable outsiders, whether they were mobsters, corrupt politicians, larcenous power brokers, or temperamental pop stars. Joe had, it was said, prevailed on Sam Giancana to help erase public records of Jack’s annulled 1947 marriage to a Florida socialite; he called upon the Chicago don again in the late fifties to smooth things between himself and Frank Costello when Kennedy’s reluctance to recognize his obligations to the New York mobster almost resulted in a contract on his life; later, during the 1960 presidential campaign, he was seen dining at a New York restaurant with a select group of top mobsters from around the country. Jack may have had all the buzz, but Joe was, in Frank’s eyes, the real man of the world in the family.

If Jack didn’t inherit his father’s intimacy with the ways of men of dark power, he had plenty of Joe’s lustful wantonness. In this, Frank made a perfectly agreeable playmate, especially when it came to the young senator’s favorite diversions—women and gossip. The two began partying together soon after Frank reconciled with Peter—“I was Frank’s pimp and Frank was Jack’s,” Lawford ruefully recalled. “It sounds terrible now, but then it was really a lot of fun.”

Whenever Jack came to the West Coast for fund-raising or other official duties, he made sure to hook up with Frank, more often than not with Peter in tow. They didn’t hide their budding friendship from the press: “Let’s just say that the Kennedys are interested in the lively arts,” Peter told a reporter, “and that Sinatra is the liveliest art of all.”

In November 1959, Jack extended a trip to Los Angeles by spending two nights at Frank’s Palm Springs estate. Frank got a huge belly laugh out of him by introducing him to his black valet, George Jacobs, and suggesting that the senator ask the mere servant about civil rights. “I didn’t like niggers and I told him so,” Jacobs remembered. “They make too much noise, I said. The Mexicans smell and I can’t stand them either. Kennedy fell in the pool he laughed so hard.”

Fun over, Jack had to return East, even though he would’ve just loved the next night, when Frank, joined by Joey Bishop, Tony Curtis, Sammy Cahn, Jimmy Durante, Judy Garland, and about a thousand others toasted Dean at the Friars Club. But he made a mental note to catch up with them the next time they’d all be together: the following winter in Las Vegas when they’d be making a movie.

It was one last bit of patrimony thrown Peter by his new best friend. Frank had taken a literary property off his hands: Ocean’s Eleven, a movie about a group of World War II vets who hold up Las Vegas.

I was told to come here

Never So Few, Peter’s comeback picture, was shaping up into quite a party, maybe even bigger than Some Came Running. After rescuing Peter from TV, Frank used his weight to get Sammy a $75,000 part. (The producers had balked, “Frank, there were no Negroes in the Burma theater.” And Frank shot them down: “There are now.”)

To Sammy, it only seemed proper: With his talent, youth, versatility, vitality, and powerful friends, he was on the verge of being the biggest star of his time.

Then he stumbled. Speaking to a radio interviewer in Chicago, he trashed Frank, just trashed him: “I love Frank and he was the kindest man in the world to me when I lost my eye in an auto accident and wanted to kill myself. But there are many things he does that there are no excuses for. Talent is not an excuse for bad manners—I don’t care if you are the most talented person in the world. It does not give you the right to step on people and treat them rotten. This is what he does occasionally.” (As a coup de grâce, asked who the number one singer in the country was, Sammy replied that it was he. “Bigger than Frank?” “Yeah.”)

It didn’t take long for him to regret his words. “That was it for Sammy,” Peter remembered. “Frank called him ‘a dirty nigger bastard’ and wrote him out of Never So Few.” The part went to Steve McQueen—one of his first important roles. Sammy, who was nearing $300,000 of debt, certainly regretted losing the work, but he was far more concerned with the way Frank had written him off.

“You wanna talk destroyed?” said Lawford’s manager, Milt Ebbins. “Sammy Davis cried from morning to night. He came to see us when Peter was at the Copacabana, appearing with Jimmy Durante. He said, ‘I can’t get Frank on the phone. Can’t you guys do something?’ Peter told him, ‘I talked to Frank but he won’t budge.’ ”

Sammy was banished from Frank’s very presence. “For the next two months Sammy was on his knees begging for Frank’s forgiveness,” Lawford recalled, “but Frank wouldn’t speak to him. Even when they were in Florida together and Frank was appearing at the Fontainebleau and Sammy was next door at the Eden Roc, Frank still refused to speak to him.” (He wouldn’t even be in the same building with him; he had Sammy banned from his shows and wouldn’t go next door to watch him perform.)

But there must have been some sort of bond there, because Frank relented, even when he had nothing in particular to gain from it. “Frank let him grovel for a while,” Peter said, “and then allowed him to apologize in public a couple of months later.”

The reconciliation went as far as new offers of work. Frank was assembling the cast of Ocean’s Eleven. He would let Sammy back in the fold in time to take a role in the movie, but one with a bit of a sting to it: For no obvious reason other than petty spite, Sammy was cast as a singing, dancing garbageman.

Sammy was nevertheless overwhelmed to be asked aboard because Ocean’s Eleven had begun to take shape as something more than just a movie. Frank decided that he would film it at his place, the Sands, and fill it with chums—everybody from Dean and Sammy and Peter to vibraphonist Red Norvo and actor buddies like Henry Silva and Richard Conte.

As a bonus, there’d be a freewheeling live show in the Copa Room each night featuring the actors. For that, Frank realized, he’d need a traffic cop, somebody who fit in with the A-list names but with the nightclub experience to get guys on and off the stage and who wouldn’t embarrass himself in front of the movie camera.

He had just the guy in mind: Joey Bishop.

Frank called him “the Hub of the Big Wheel” and preferred him to almost every other stand-up comic. He addressed the world with a stiff-shouldered, side-of-the-mouth delivery that was as much jab as shrug, a deft emcee who knew how to keep the show moving and not draw attention from the stuff the people really came to see.

But nevertheless, to most observers it was the Big Mystery of the Rat Pack: What was Joey Bishop doing up there?

Frank, Dean, and Sammy were clearly peas from the same pod, and Peter was a guy who swung like them and provided entrée to the Kennedys.

Joey, however, had neither powerful relatives nor a reputation as a roué, and as performer he was plainly one-dimensional: He acted about as well as Sammy, sang about as well as Peter, danced about as well as Dean.

But he had an air about him—the world-weary little guy with the plucky, jaded attitude—that appealed to Frank, who indirectly sponsored his career from the early fifties on. Other comics would try to win an audience with dazzling wit or class clown antics. Joey went the other way, wearing a stage face that suggested he found the idea of entertaining the crowd slightly undignified. It was largely a matter of style—“My technique is to be overheard rather than heard,” he liked to say—but there was temperament there as well.

“My cynicism is based upon myself,” he told a reporter in a self-analytic moment. “I don’t tell audiences to be cynical. I just bring them down to reality. I feel that when you try to cheer somebody up, you probably have a guilt complex. When a child sulks, eventually you ask him what’s wrong because you probably feel you’re the reason he’s sulking.”

He should’ve known. For a guy best known as a chum among chums, he could be taciturn, moody, aloof, exclusive. Even when he was among the honored guests at the Party of Parties, he kept to himself. “I was always a go-homer,” he admitted. “When we were doing the Summit Meeting shows in Vegas, the other guys would stay up until all hours, but I went to bed. I may rub elbows, but I don’t raise them.”

In fact, he gave off an almost perverse aura, as if he resented his own success and the hand his padrone, Frank, had in it. “I met Frank in 1951,” he said, “and, sure, he’s helped me a lot. We’ve worked together many times, and I enjoy it, but we don’t socialize afterwards.” And he didn’t care if he pissed him off. During the Summit, Frank was feuding with a Vegas club owner and declared the guy’s joint officially off limits; Joey, the story went, went anyhow.

His independence was his trademark, his currency, and he gambled that Frank would read it not as insolence but rather a sign of maturity and maleness. It almost backfired. “I have always respected Frank’s moods,” Joey recalled. “I have never walked over to Frank when he’s having dinner with someone and just sat down uninvited. Which, I think, was another reason why he chose to have me with him. Then it got to the point where he would say to me, ‘What’s the matter, Charlie? You’re getting stuck up?’ ”

It was a fine line that he braved. Reporters who got close to him during the Rat Pack era seemed genuinely to like him, but few of them depicted him as, in the cliché of the showbiz puff piece, rough on the outside but sweet at heart. “You can pretend to be happy if you want to,” he told one; “I’m a worrier by nature,” he confessed to another. “No worrier is ever good-humored. I don’t know if a worrier ever is happy.”

Of all the moons in Frank’s orbit, only Dean had anything like Joey’s need for independence. They were the only ones who ever seemed willing to do without Frank’s blessing—or even to outright defy him. Maybe it was because they had a few things in common. Unlike Sammy, Frank, and Peter, they’d grown up with siblings and stable homes, and their career successes came relatively late in their lives. Dean was thirty when he broke through with Jerry Lewis; Joey was nearly forty when the public and the business started taking real notice of him.

He’d had a few brushes with the big time, and their failure to materialize seemed to cauterize him against the world all the more: “Once, when I was sharing a bill with Frank at the Copacabana, the audience kept me going 28 minutes overtime almost every night,” he told a reporter. “Frank kept telling me, ‘You’re solid now—you’re on your way’ Know what happened? I didn’t work for six weeks.”

It was the kind of mixed success his career had accustomed him to. He’d been trying to make it big for more than twenty years when he was picked by Frank for the cast of Ocean’s Eleven. Prior to that, he’d glimpsed the top frequently enough to develop a sardonic attitude about not ever having reached it. He was a plugger, and he knew it: “I’m a slow starter. There can never be a big, hitting thing with me … I don’t have the type of personality that shatters you right off. I have to work at being funny. The work is hard. I’m hard sometimes.” That way he had of dismissing things, deflating things—it came naturally to a guy who’d had to fight for everything and even then didn’t quite get it.

He was born in the Bronx in 1918, the fifth and last child of Jacob Gottlieb, a machinist and bike repairman, and his wife, Anna. He was sickly—the littlest baby, he used to brag, ever born in Fordham Hospital (he told the story to an incredulous Buddy Hackett, who responded with a look of concern, “Did you live?”). At three months, the family moved to Philadelphia, where the slight baby grew into a slight child.

The Gottliebs never had much money, and the kids learned to tiptoe around Jacob, who was always irritable with the vagaries of his business. He could be nurturing, encouraging Joey and his older brother Morris in pursuing music (Jacob himself played the ocarina and sang Yiddish songs), but he could also terrify them—a kid could get spanked for the mere offense of coming home with a dime, a sum their father believed no child could earn honestly. Joey, who began his schooling as an apt, engaged student, once won a fifty-cent prize in a spelling bee; when he came home, he caught a beating from one of his brothers who, in imitation of Dad, was certain the money was stolen.

After that spelling bee, Joey did nothing to distinguish himself as a student other than quit altogether after two years of high school to work in the bike shop. It was a dispiriting experience—“What would anyone want with a bicycle during the Depression?” he asked a reporter years later—and being around Jacob all day was no picnic. Joey took on work in a luncheonette and then decided he’d move to New York to try and break into show business.

Show business? Okay, maybe he was funny around school and the shop, always ready with a cocky, cutting jibe, and he’d won a few amateur-night contests with his patter, his impressions, even a bit of tap dancing. But this wasn’t exactly the sort of ambition Jacob had tried to instill in his sons—“It was a choice of either getting a steady job or getting killed,” Joey remembered. He told his folks he’d stay with relatives in Manhattan and keep a day job; they gave him the green light. For a brief moment, it looked like he might pull it off—he worked in a hat factory by day and got a gig as an emcee in a Chinese restaurant on Broadway at night. But soon enough he was back with the smock and the spokes and the inner tubes in Philly, a flop.