Полная версия

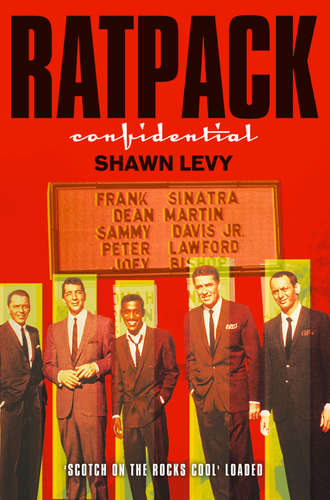

Rat Pack Confidential

“You look like a goddamn rat pack,” she muttered.

It broke them up. A few nights later, back in Romanoff’s joint in Beverly Hills, she walked in and declared, “I see the rat pack’s all here.” Again, a big hit, but this time the joke picked up momentum of its own: They founded an institution—the Holmby Hills Rat Pack. They drew up a coat of arms—a rat gnawing on a human hand—and coined a motto: “Never rat on a rat.” And they assigned themselves ranks and responsibilities: Frank (and you can just see him standing there excitedly conducting the whole sophomoric enterprise) was named Pack Master; Bacall, Den Mother; Garland, Vice President; Sid Luft (Garland’s husband and manager), Cage Master; Lazar (so full of pep they gave him two jobs), Treasurer and Recording Secretary; and humorist Nathaniel Benchley, Historian.

Bogart was named Rat in Charge of Public Relations, and the next day he spoke about the whole silly business with movieland reporter Joe Hyams. “News must be pretty tight when you start to cover parties at Romanoff’s,” Bogart responded when asked about the Rat Pack, but, assured that the story would be treated with such overblown pomp that it would obviously be seen as a goof, he acceded to an interview. The Rat Pack, he declared, was formed for “the relief of boredom and the perpetuation of independence. We admire ourselves and don’t care for anyone else.” They’d briefly considered adding some absent friends to the roster, he said, but the requirements were often too high: When Claudette Colbert, for instance, whom they all liked, was nominated, Bacall insisted that she not be admitted because she was “a nice person but not a rat.” Hyams dutifully jotted it all down, agreed once again when Bogart insisted that “it was all a joke,” and reported it the next day in the New York Herald Tribune.

Hyams’s scoop was true enough: There was indeed a group, centered around Bogart, that hung out together to the exclusion of the remainder of Hollywood, which, though they were part of it, they had no qualms about mocking. “You had to be a noncomformist,” said Bacall, “and you had to stay up late and drink and laugh a lot and not care what anybody said about you or thought about you” (one last criterion: “You had to be a little musical”). But the idea of an organization and a creed and all that, that was strictly a lark, another of Bogart’s beloved practical jokes taken to an absurd height.

Nevertheless, the publicity incited a reaction that revealed that Bogart’s attitude wasn’t necessarily laughed off by the world at large. Hollywood was an extremely cliquish society, and Bogart’s clique had always taken the perverse ethical stand that the local social mores—and the cliques it spawned—were bullshit. The notion of such a disdainful group legitimizing itself into an honorable cult, even in jest, struck some in the movie colony as an affront.

The poor schmucks didn’t get the joke: There was no such thing as the Rat Pack, not really. The principals might all get together at Romanoff’s or Bogart’s house and carry on like a drunken fraternity, but that’s all they really were: There were no dues or meetings or minutes or rules; there were just nights together in a company town of which they were all valued—and jaded—assets. If they wanted to pretend they were wild rebels, fine; they still all showed up on movie sets and in recording studios bright and early the next morning with their material prepared and their bodies and voices ready to perform. The whole Rat Pack thing was like bowling or square dancing or watching TV—the things they would’ve done together if they’d been squarejohns living between the coasts and not movieland royalty.

The subtle caste system out of which the Rat Pack arose became somewhat more manifest in 1956 when Bogart was diagnosed as having incurable throat cancer. A parade of friends, colleagues, and acquaintances spent the ensuing year paying fealty to this man who neither wanted nor acknowledged their sympathetic indulgence. “Haven’t you people got anything better to do than come over here and bother me?” Bogie would admonish his guests. “How am I supposed to get any rest with the likes of you coming every day?” It was the sandpaper wit they’d come to expect from him, and they cherished it.

Despite his crusty bravery, though, the last year of Bogart’s life was a horror of weight loss, discomfort, incapacity, depression. Bacall, still in her early thirties and an established star in her own right, bore it as well as she could, but she needed occasional escape from the traumatic scene unfolding in her home. Bogart insisted that she continue to go out on the town, and he was grateful whenever she took him up on the offer, most frequently escorted by Sinatra.

Frank had determined to remain steadfast during his idol’s illness, visiting regularly even though he was mortified by Bogart’s condition. “It wasn’t easy for him,” Bacall remembered. “I don’t think he could bear to see Bogie that way or bear to face the possibility of his death. Yet he cheered Bogie up when he was with him—made him laugh—kept the ring-a-ding act in high gear.”

More than that, it has been suggested, he filled the loneliness in Mrs. Bogart’s life with more than just suppers at Romanoff’s. Intimates of the group whispered about a budding love affair between Sinatra and Bacall—“It was no secret to any of us,” said one—and they pointed to a Rat Pack trip to Las Vegas for Bacall’s birthday which Bogart skipped, preferring to take his young son, Stephen, to sea on the Santana.

Bacall was aware of the dynamic, admitting that Bogart “was somewhat jealous of Frank. Partly because he knew I loved being with him, partly because he thought Frank was in love with me, and partly because our physical life together, which had always ranked high, had less than flourished with his illness.”

When the end finally came, Frank, a fixture in the Bogart household, was nowhere to be found. Bogart died on January 14, 1957, when Frank was in New York working a club date at the Copacabana. He canceled three days’ worth of shows (Sammy, who was starring on Broadway in Mr. Wonderful, and Jerry Lewis, who was in the midst of a successful solo run at the Palace, subbed for him), but he didn’t return to California for the funeral, holing up instead in his Manhattan hotel.

Even if he didn’t have any reason to feel guilty, he couldn’t have been too comfortable back on Maplewood Drive. Bogart’s house had become a kind of shrine to his final days: His favorite chair, his clothes, his photos, his very aura hung about the place unaltered. Bacall couldn’t bring herself to change a thing, even though she, too, found it difficult to live amid it all. Frank—always indulgent of widows—gave her and her children the run of his Palm Springs estate for as long as they needed it.

By the end of 1957, the time had arrived when he could offer her more. His Mexican divorce from Ava Gardner, a mere legal technicality in their shattered relationship, had coincidentally come through that June. Frank and Bacall began seeing one another socially, with all observers assuming they were intimate. When Frank entertained at his homes in Coldwater Canyon or Palm Springs, Bacall was hostess, and she was his date for the Las Vegas premiere of Pal Joey and the L.A. premiere of The Joker Is Wild. It made perfect sense: the Pack Master and the Den Mother, a golden couple come together after their storied marriages had ended, respectively, in passionate disaster and heart-wrenching tragedy.

Despite the fairy-tale appearance of the romance, though, they had to endure one another’s considerable faults. Bacall got into the habit of checking up on him whenever he was with other women—taking a phone call from her while his latest conquest listened along in his hotel room, he made a big show of his impatience, answering, “Yes, Captain. Yes, General. Yes, Boss.” In exchange, she was subject to Frank’s moodiness. His swings between indulgent companionability and icy remove rattled her, especially, as she noted later, since she had previously “been married to a grown-up.”

But her will was no match for his; like many of Sinatra’s women, she was eager to do anything to please him. She even went so far as to give up her home on Maplewood Drive, in part because of the painful memories the place harbored for her, in part because, as she later told her son, “I don’t think Frank was comfortable in that house. The ghost of your father was always there and I knew that Frank would feel better if I moved.”

Her sacrifices and persistence paid off: In March 1958, after another of his sullen absences, he popped back onto the scene and proposed marriage. She accepted, agreeing to his desire to keep their intentions private for a while. Frank went off to a club date at the Fontainebleau; Bacall stayed in L.A. and kept denying rumors whenever reporters—even buddies like Joe Hyams and Richard Gehman—got snoopy. But she couldn’t keep from blabbing to gossipy little Swifty Lazar, who spilled the beans to Louella Parsons, who made national headlines with it, which drove Frank into a fit.

“Why did you do it?” Frank harangued Bacall from Miami. “I haven’t been able to leave my room for days—the press are everywhere. We’ll have to lay low for a while, not see each other for a while.”

Chastened, even in her innocence, Bacall did as she was told—and Frank never tried to contact her again. “He behaved like a complete shit,” she later said. “He was too cowardly to tell the truth—that it was just too much for him, that he found he couldn’t handle it.”

But there might have been a bigger truth: Maybe Frank had realized that he didn’t have to marry Bogie’s widow to become the actor’s true heir and King of the Rat Pack. Maybe he realized that he could simply up and start a brand-new Rat Pack of his own.

105 percent

By at least one account, it was Dean’s idea: The story goes that he had just rescued his career with his eye-opening work on The Young Lions, and he was sharking for a new project. In the summer of ’58, he and his wife attended the premiere of Kings Go Forth, Frank’s latest picture, and he walked over to Frank like he was pissed about something.

“You bum!”

Frank played along: “What’ve I done now?”

“You’re hunting for a man for your next picture who smokes, drinks, and can talk real southern. You’re looking at him.”

“Well, whattaya know …”

Cute. And there might even be some truth to it, but the likely scenario is somewhat less colorful. For starters, if it had happened, it would’ve marked the first time in his life that Dean Martin went out of his way to further his career; indeed, one of the reasons for the dissolution of Martin and Lewis was that Jerry’s overweening ambition struck Dean as degrading. More than that, the story assumes that Frank, who was forever throwing his chums roles in his movies (he once slated his squeeze Gloria Vanderbilt for a role in the western Johnny Concho, an inspiration lost to cinematic history when their love affair hit the rocks), hadn’t already considered Dean for a role that he was practically born to play. In fact, it ignores altogether just how close Dean and Frank, a couple of olives off the same tree, had recently become.

For their first couple decades in the business, they hadn’t palled around much, even though they’d been crossing paths since the war. Dean’s big ticket to New York came when he followed Frank into the Riobamba nightclub; they shared a record label; they had appeared together on TV a few times; but they were no more a two-act than, say, Perry Como and Vic Damone.

Recently, though, that had begun to change. A couple of years earlier, Dean took in a Judy Garland show in Long Beach in Frank’s company (Sammy and Bogey were also there), and they all popped onstage with the star for an impromptu number. After that, Frank appeared on a couple of Dean’s NBC specials—on one, they sang a duet of “Jailhouse Rock”!—and Dean returned the favor when Frank began his catastrophic series on ABC.

Frank had grown to feel something fraternal for Dean. He would always be the first mate, a brother.

But it hadn’t always been that way.

“The dago’s lousy, but the little jew is great”: thus Frank on Martin and Lewis, circa 1948, when the new singing-comedy act was tearing the roof off Frank Costello’s Copacabana and quickly becoming the hottest thing in showbiz.

In a sense, it was an entirely apt critique. Martin and Lewis, one of the greatest two-man acts in history, was really Jerry Lewis’s vehicle. Dean, the tall, handsome, crooning straight man, was more or less along for the ride. And when the ride ended, when Martin and Lewis devolved into an ugly spitting contest and finally broke apart, “the little jew” went on to solo success, just as everyone predicted, while “the dago” initially floundered.

It wasn’t that Dean didn’t have the chops. He had a charming voice in the Crosby mood—a stylish singer, if never a real artist. He cut a great figure in a tux, golf clothes, even overalls: real movie star looks. And he was funny, with a gift for whimsical one-liners and a canny, low-key delivery that were completely wasted in the years he spent alongside the spotlight-hogging Jerry.

But he seemingly didn’t have the drive to go it alone. He was ten years older than Jerry and struggling under an absurd burden of debt when the two teamed up and launched their rocket to the moon. For all his gifts, he’d never, as a solo, gone anywhere useful. And for all the success that he eventually enjoyed, it seemed like the only reason he’d ever gotten anywhere at all in the world was that he’d been somehow blessed to thrive in it. He didn’t have to work, he didn’t have to sweat, he didn’t have to think; he just had to show up and get paid—his whole life long.

Consider: Dean never wanted to get his hands dirty, so he learned how to deal cards and how to sing, and he made a living at it; he was too sanguine to chase women, so they threw themselves at him; he didn’t have the fire in the belly to make himself a showbiz star, so he met a couple of wildly ambitious guys—Jerry and Frank—who dragged him along.

It was even luck that Dean was born in America—his father’s bad luck, that is, to have been born in Abruzzi, a wind-scored plain south of Rome, dotted with cave-riddled mountains. Abruzzi spit forth disconsolate young men and women and exiled them to the New World, where they choked slums and factories. Steubenville, Ohio, where Dean’s people turned up, was filled with steelworks that swallowed up Italian and Greek immigrants like so much coke.

After seeing the infernal wreckage of his older brothers, who’d emigrated before him, Gaetano Crocetti, Dean’s father, decided that selling his soul to a foundry wasn’t for him. He chose instead one of the few respectable blue-collar jobs open to a young Italian immigrant, apprenticing himself to a barber. With his name anglicized (he became Guy Crocetti, pronouncing his last name Crowsetti) and his future assured, he was able to woo and wed Angela Barra, an orphan girl from the neighborhood with a bit of barbed wire in her makeup. They were kids when they married, but by June 1917, just three years later, Guy had his own barbershop, the couple had a one-year-old boy, and Angela produced another son. Born prematurely, he wasn’t christened until the fall: Dino.

The Crocetti boys were raised among a healthy tribe of relatives and neighbors. They had a comfortable home, plush Christmases, plenty to eat; there were no riches, exactly, but nor were there rags. Guy was naturally easygoing—a good barber. He sat genially among the other men, sipping wine, eating tangerines and nuts, schmoozing away the twilight in the Abruzzese piazza that they simulated in their hearts and minds.

But Angela had grown up under more brutal circumstances than her husband—her mother had been committed to the Ohio Institution for the Feeble Minded—and she didn’t see the world as so accommodating a place. She spoiled her sons like any good Italian mother, true, but she also tried to prepare them for the world by instilling her toughness in them, teaching that they mustn’t be weak or free with their feelings, that they should make their way in the world like men.

Dino learned such lessons well. Like his dad, he refused to submit to a future in the foundries, but he wasn’t soft enough for barbering. His mother’s strength had given him the confidence to seek other opportunities—of which Steubenville was deliriously full. In fact, the town, known throughout the region as Little Chicago, was wide open: pool halls, strip joints, cigar shops fronting for gambling parlors; only a sucker, it seemed, could grow up amid it and not try to cash in.

By his early teens, Dino was running with a shady gang from around the neighborhood and showing up in school with his pockets full of silver dollars. At sixteen, he slipped out of school altogether and for good. He was tall and athletic, with dark, wavy hair and a bold Roman nose. He tried to turn his good looks, lithe body, and quick hands into a profit as a welterweight boxer—Kid Crochet. He flopped. So he turned to odd jobs, including a brief, terrifying stint in a steel mill—a vision of hell as a place where you spent eternity if you lacked the moxie to avoid it. He finally broke through into the sort of racket to which he aspired: dealing poker and blackjack in a local gambling den.

He took to fancy clothes and easy women. He and his pals ran around nights drinking, gambling, carousing. Guy and Angela disapproved, but their boy breezed along in merry indifference: Good times like these, who worried about the future?

Yet even though he was always one of the boys, there was something in Dino that set him apart: He sang—a fanciful affectation, perhaps, but one acceptable to Italian boys of his age, partly out of the respect accorded opera singers in their culture, and partly because of the novelty of the radio and the phonograph, which was making stars of crooners. It was the only thing that Dean applied himself to that didn’t have the spoor of sin about it; he even took vocal lessons from the mayor’s wife. And he performed in clubs and taverns and at parties whenever there was an open mike and a band willing to back him.

His pals encouraged him; his bosses liked it. Soon enough, he took work as a singing dealer at a sneak joint outside of Cleveland. He was approached by Ernie McKay, a bandleader from Columbus who offered to take him on. Before long, another eye was caught: Cleveland bandleader Sammy Watkins hired him away in the spring of 1940 to come to the shores of Lake Erie and play to a ritzier clientele.

That winter, performing under the newly minted stage name Dean Martin, he met a fresh-faced college dropout named Elizabeth MacDonald. Two years later, they married. Nine months after that, Dean was a father looking for a way to make more money.

A local MCA agent called: Frank Sinatra had canceled a date at the Riobamba in New York, and the club’s owners were willing to give this new Italian boy singer from Cleveland a shot. Dean wanted to go, but he had to pay a steep price: For freedom from his contract, he gave Watkins 10 percent of his income for the next seven years; the agent took another 10 percent. In September 1943, at $150 a week, he debuted in Manhattan, the world’s biggest candy store for a guy with his kind of sweet tooth.

The obvious pleasures aside, New York didn’t prove easy. Money didn’t come fast enough, and when it did, it disappeared even quicker. Hands reached into his pockets. An old Steubenville acquaintance turned up wanting to serve as his manager, offering $200 ready cash in exchange for a 20 percent piece of his earnings. Dean was in debt everywhere; he took the deal. He was courted by a Times Square agent who offered another cash payment for 35 percent of his earnings; he took it. Comedian Lou Costello offered Dean more money for another 20 percent; he took it.

Dean got his patrons to broker a nose job, turning the schnozzola he’d inherited into something more aquiline. He signed up for a nonsponsored radio show whose musical director took an interest in his future. Dean milked the guy for yet another cash payment in exchange for 10 percent of himself, making a grand total of 105 percent; for every dollar he earned, had he been up front with all his partners, he would’ve been out a nickel—but, of course, he never bothered to pay anybody.

In August 1944, he was booked into the Glass Hat nightclub, just another gig that only changed his life forever. Down the bill and serving as emcee was a skinny, acned kid pantomimist from New Jersey named Jerry Lewis: destiny with an overbite.

Like everyone else, Jerry adored Dean, and he grabbed every opportunity he could to pal around with him at gigs, at restaurants, at after-hours schmoozes. He even began edging into Dean’s act. In the winter of 1945, when Dean was topping the bill at the Havana-Madrid club and Jerry was emcee, Jerry kibitzed from offstage as Dean sang. Dean didn’t care much about what he was doing anyhow, so he played along, getting an appreciative rise out of the crowd.

The following summer, Jerry was playing the 500 Club in Atlantic City, a joint with ties to the Camden mob, and he found himself on the verge of being fired. He called New York in a panic, found out that Dean was available, and told the guys who ran the club that Dean was a great singer and that the two of them did “funny shit” together. Management bit, Dean got hired, and one of the brightest Roman candles ever to hit showbiz was lit.

Within a year, Martin and Lewis were the biggest act in nightclubs; two years later, they were the biggest act in the world: TV, movies, radio—they overran every single medium available to them. They made sixteen hit films, had the nation’s number one TV show, and were one of the top-drawing live acts in the business, creating a sensation that recalled nothing so much as Sinatra’s bobby-sox heyday; they even tied up traffic in Times Square.

The act was a farce, equal parts nightclub slickness and burlesque puerility. Dean would stand soberly (the drunkie routine didn’t start till after Jerry) and try to put over a tune—“Oh, Marie,” say, or “Torna a Sorriento”; Jerry would cavort wildly, trying to horn in on the act or take control of it for himself—a realer bit of shtick than anyone in the audience knew.

Of course, Dean could actually sing as well as play straight, combining the best of George Burns and Desi Arnaz with sex appeal neither of them had. But the point of Martin and Lewis was no more straight vocals than it was dramatics. Jerry would squeal and wheedle and practically run out and kiss the audience’s ass to gain its love, and Dean would stand in dumbfounded awe of the spectacle, a substitute for the viewer, bemusedly, indulgently watching as his little buddy made a travesty of the accepted forms of showbiz. If Dean occasionally dove in and capered as well, that made it even more fun; for the most part, though, he hung back and let Jerry make a merry schmuck of himself.

This was the Dean Martin that the world came to love—the suave geniality covering up the calculating hedonism, the easy affability that belied the inner selfishness, the game sport whose willingness to go along with his wacky partner onstage was utterly at odds with the taciturn midwestern reserve that marked him when the arc lights dimmed. For four decades, he would project as much dignity and self-assurance as he ever did sauce or testosterone or jaundice.

The public loved him and it loved his partner and it loved the two of them together. Even when he divorced Betty and married Jeannie Biegger, a gorgeous-blonde beauty queen from Miami, he couldn’t tarnish the golden glow of Martin and Lewis.

It took the two of them to do that.

By 1954, they weren’t such good pals anymore. Jerry was styling himself a creator of artful comic narratives in a variety of media. He sought publicity and creative control—something, ultimately, other than partnership—and he couldn’t stand to sit beside his pool for more than a few hours without setting himself to some sort of project.